M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

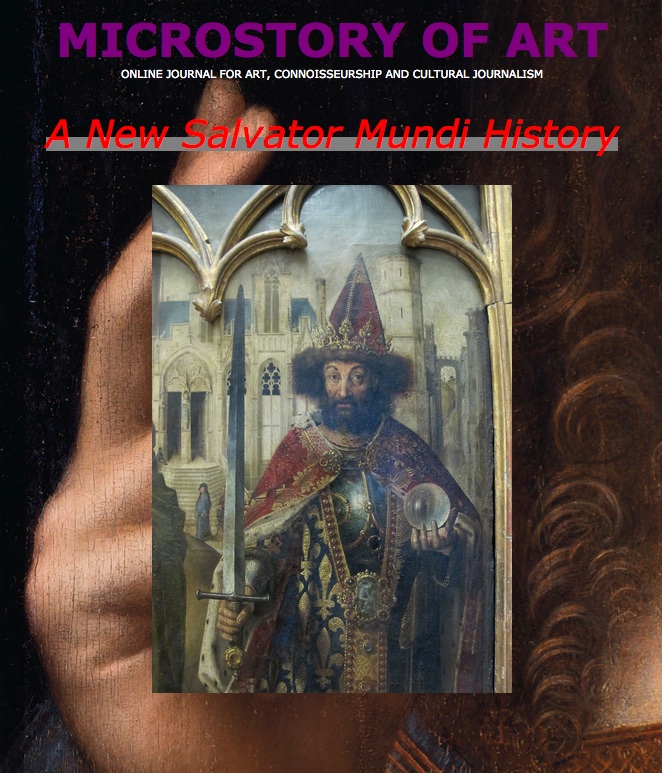

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

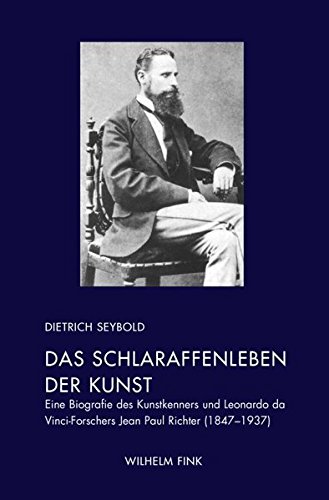

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

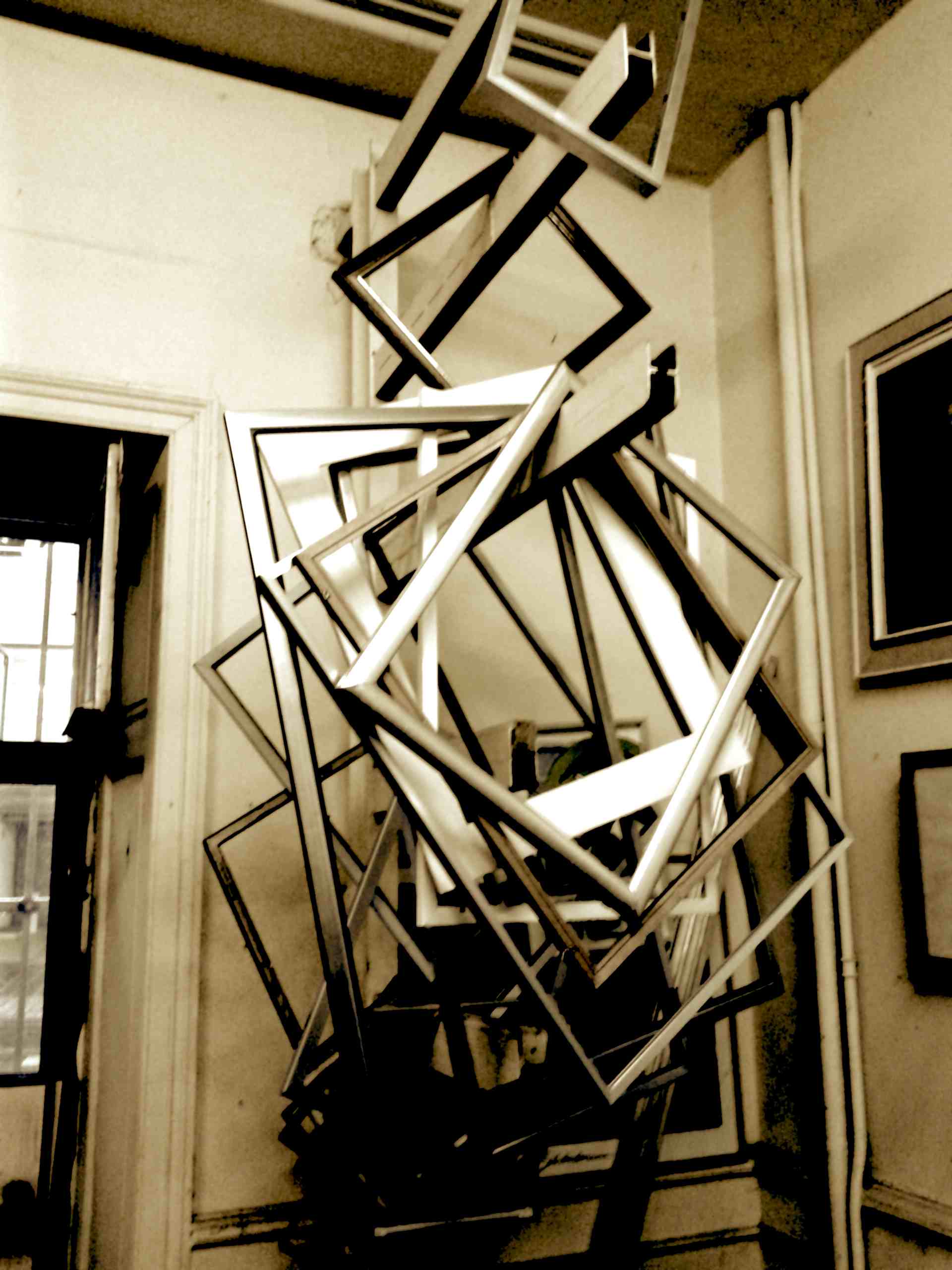

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

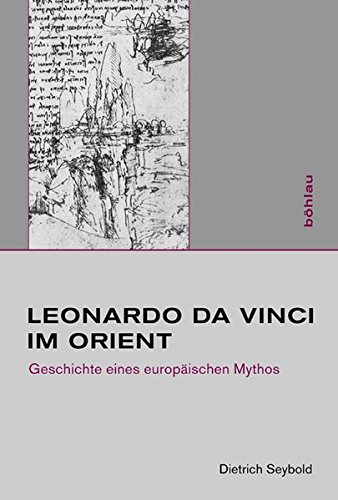

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP This section, dedicated to the various branches of connoisseurship, its various tribes, customs and practices, and especially to the interchange of ideas between various branches, i.e. the mutual inspiring and the challenging transposing and transmitting of ideas from one branch to another, opens with my essay on Friedrich Nietzsche. Entitled The Professor And His One Student or Friedrich Nietzsche On Connoisseurship  (Picture: chechar.wordpress.com) |

(Picture: DS)

(Picture: Basel-virtuell.ch) ›Haven’t you heard‹, his fellow professors might have whispered, in the corridors of the now so-called Alte Universität of Basel, in 1876, ›Collega Nietzsche has had just one single student in his lecture (and that one did even arrive too late). But he was very dignified, our Collega Nietzsche, and we heard him giving a »philosophical intermezzo« instead of going on with his regular lecture, accompanied by the organ tone of the rushing river Rhine. And he did speak, beautifully, of Heraclitus (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heraclitus) to that one student.‹  View from the Alte Universität building upon the Rhine (picture: DS) |

Yet before we go into that story, I have to tell another one that I have experienced myself. Not in the Alte Universität, but in the newer building at Petersplatz. And it must have been in the early 1990s when one professor of history introduced another one, a guest professor from East Germany, and had the guest professor announce the lecture and seminary that the guest professor was planning to present and to hold, respectively, since, as was becoming clear, despite the early morning hour and despite of everyone being rather still kind of asleep (I believe it was around ten), that the guest professor from East Germany had yet not enough students (or even one single student) in his lecture and seminary. I recall the fresh and openly inviting manner with which the guest professor invited everyone of us to his lecture and seminary about the history of East German mining and metallurgy at the times of Luther, and when the guest professor from East Germany ended by asking if some of us (the lecturing hall was actually very crowded) wanted to join this lecture and seminary on the history of mining and metallurgy at the times of Luther (the professor did ask individually as to the lecture and as to the seminary) not one single hand did rise. Actually nobody did move at all, as everyone seemed to be frozen or petrified. Upon which the guest professor, if it was in shock or not, did mumble some note of thanks and left the lecturing hall very swiftly (and the other professor started his own lecture as if nothing had happened). |

| I remember this scene quite vividly as one example of self-humiliating in front of an audience that I have stored in my memory, but I am not quite sure anymore if it was this at all. At this early morning hour, however, not one soul reacted to the kind invitation, and one particular detail of the whole scenery that I recall very in particular (and maybe this image is the actual carrier of my own recollection) is that one female student’s turning to her neighbor (she sat in the row in front of me), a turning to her neighbor because of feeling uneasy with the seen and heard, a bodily gesture as if saying: we did not want this to happen at all, but (this is now my interpretation) this way of confronting us was, giving our standards, far to direct, and in adressing us as an audience, i.e. as a collective, you cannot expect us to react immediately and individually to your kind offer of joining the lecture and seminary on the history of mining and metallurgy, you have to give us time to think about it, and maybe the one or other student will find his or her way into your lecture and seminary. This interpretation may sound somewhat too rational, but the gesture, the turning to her neighbor with an expression of pain in her face, in any way, was certainly a gesture of compassion. At any rate: I do recall also a student who actually did join the seminary speaking, later, very positively about that professor’s knowledge as to the history of mining and metallurgy, and this professor from East Germany must have been a real expert (or connoisseur) as to that branch of knowledge). And in the end I am not quite sure if this collegue of mine was actually the single one student in that particular seminary. He might have been, but I do not recall. And the history of mining and metallurgy does sound more interesting to my ears today, as it sounded then, at that early morning hour at Basel university. |

*

Back to the Alte Universität (picture: Basel-virtuell.ch)

»The rushing of the Rhine was the only sound, when we both, stricken, for some moments, kept silence.« Thus Ludwig von Scheffler, in his account of being the one student that Friedrich Nietzsche, in 1876, presented his »philosophical intermezzo« on Pre-Socratic philosophy and especially on Heraclitus to. Spoken into the loud rushing of the river Rhine, and since this is hardly imaginable today (be it for the modern windows, or for the river that is not rushing anymore), probably almost at water level. »Then, however, something strange occured. Nietzsche did not keep his mood, as usual, in keeping silence, but, in a cheerful tone, explained to me that he was going to accompany me to my apartment. He had business to do with my landlord who was his insurance agent, and beyond that he was tempted of getting to know of how one lived at ›Blumenrain‹ […].« |

| And thus the professor and his one student did walk down the Rheinsprung, with Nietzsche complaining about the permeable paving, and the student, who was obviously feeling a trifle uneasy while holding his professor’s arm, drawing his teacher’s attention to the cumulative white summer clouds: »›As Paul Veronese is painting them!‹ I passed the remark, half to him, and half to myself. Nietzsche looked up there, stopped in musing; ›and they are drifting!‹, he added like in a soliloquy. But then, all of a sudden, he unclasped my arm, only to clasp it, equally fiercly with both hands: ›I am going to travel soon… Holidays are almost here… Will you come with me?! Shall we see the clouds drifting in Veronese’s home country?!‹« This did not happen though, since the student, rather being shocked by this unexpected invitation, started to beat around the bush, making some excuses, upon which Nietzsche, for a brief moment, showed a distorted face, a mask, but found back to his professoral dignity, and the trip apparently did end at Blumenrain.  * |

| It is a very short walk from the Alte Universität building down to Blumenrain. The Rheinsprung that leads you downwards to the bridgehead is rather narrow, and the more narrow the space, the easier to imagine that the atmosphere of this walk, the student and his one professor walking arm in arm, must have been rather remarkable, if somewhat tense. To recreate this walk we use photographs, taken on September 20 (the other pictures are taken earlier), a day with particularly impressive formations of clouds, and also a rather crowded Saturday afternoon to walk across a cityscape. And Scheffler, who actually was a student of art historian Jacob Burckhardt, did not only compare the clouds of that summer day in 1876 with the clouds rendered by Veronese, he also compared the way Nietzsche had just had mental images of the Pre-Socratic Greek philosophers appear in front of the student’s inner eyes with a »shimmering cloud«. If anything is invented or stylized in Scheffler’s account – it is well invented or stylized. Because this account, originally published in 1907, brings out much. I image that Scheffler’s respect for Nietzsche had grown over the time, and that the somewhat refractory young student had found his professor’s behaviour even more strange that the later account reveals (although, according to his own testimony, it had been the student who had offered his arm to the professor, and although the student seems to have felt already then that Nietzsche had identified to some degree with the solitary philosopher Heraclitus). To recreate the atmosphere, however, we cannot rely upon images alone. Scheffler, who was very observant on how Nietzsche did speak and therefore for his carefulness with words (and this is something that the text of 1907 brings out very well), was obviously impressed also by the lecture’s content. And this is why we quote the very passage that Nietzsche might have read to the one student, who did feel so well that his professor was a connoisseur of words – and had the highest respect for the connoisseurship of words: in one word: for the discipline of philology, a discipline that Nietzsche was to compare, some years later, with the »art and connoisseurship of goldsmithery«. »Von dem Gefühl der Einsamkeit aber, das den ephesischen Einsiedler des Artemis-Tempels durchdrang, kann man nur in der wildesten Gebirgsöde erstarrend etwas ahnen. Kein übermächtiges Gefühl mitleidiger Erregungen, kein Begehren, helfen, heilen und retten zu wollen, strömt von ihm aus. Er ist ein Gestirn ohne Atmosphäre. Sein Auge, lodernd nach innen gerichtet, blickt erstorben und eisig, wie zum Scheine nur, nach außen. Rings um ihn, unmittelbar an die Feste seines Stolzes, schlagen die Wellen des Wahns und der Verkehrtheit: mit Ekel wendet er sich davon ab. Aber auch die Menschen mitfühlender Brust weichen einer solchen wie aus Erz gegoßnen Larve aus; in einem abgelegnen Heiligtum, unter Götterbildern, neben kalter, ruhig-erhabener Architektur mag so ein Wesen begreiflicher erscheinen. Unter Menschen war Heraklit als Mensch unglaublich; und wenn er wohl gesehen wurde, wie er auf das Spiel lärmender Kinder achtgab, so hat er jedenfalls dabei bedacht, was nie ein Mensch bei solcher Gelegenheit bedacht hat: das Spiel des großen Weltenkindes Zeus. Er brauchte die Menschen nicht, auch nicht für seine Erkenntnisse; an allem, was man etwa von ihnen erfragen konnte und was die anderen Weisen vor ihm zu erfragen bemüht gewesen waren, lag ihm nicht. Er sprach mit Geringschätzung von solchen fragenden, sammelnden, kurz »historischen« Menschen. »Mich selbst suchte und erforschte ich«, sagte er von sich, mit einem Worte, durch das man das Erforschen eines Orakels bezeichnet: als ob er der wahre Erfüller und Vollender der delphischen Satzung »erkenne dich selbst« sei und niemand sonst.« |

(Picture: DS)

This is where they, professor and student, might have stopped to watch the clouds. On the right the building of the Alte Universität is still in frame.

The building is, as can be seen, in restoration as for the lowest level, where Friedrich Nietzsche must have given his lectures.

The year of 1876 was, by the way, a year of floods in spring. In the background the ›tower of Basel‹, under construction, can also be seen (picture: DS).

| We have left the Alte Universität building with a photocamera at hand, in case we would come across a philosopher and his one student. The pavement is not that bad in our days, many construction sites, however, bother any Basel (late) summer. But, next to the views, it is the shopwindows that draw any tourist’s attention. In walking down, we immediately come across the first goldsmith’s or jeweller’s shop window. And it would be worth to find out if the city of Basel was as crowded by goldsmiths at Nietzsche’s times as it is today. Pens and inks, in many varieties, follow a few steps further down Rheinsprung, as we are walking down towards Blumenrain, with Heraclitus’ sayings in mind: ›No man ever steps in the same river twice‹ (because it is not the same waters again, for there is constant change; a saying, according to modern scholars only attributed to Heraclitus) and ›Donkeys prefer garbage (or strewing, as Nietzsche has it) to gold‹. * Two basic concepts of how to think connoisseurship we find in Nietzsche’s oeuvre. The very positive view of connoisseurship, as mentioned before, is associated with philology (and finds its metaphor in goldsmithery). But at the time Ludwig von Scheffler walked down Rheinsprung, arm in arm with Nietzsche (and maybe looked also into the one or other goldsmith’s shopwindow), the latter had not yet published the before mentioned metaphorical passage, nor his praise of the poet Horace (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace) that was to follow in 1889 and bears testimony to Nietzsche’s love of poetic structures of language. Yet Ludwig von Scheffler, the student, who later, as a man, recalled that vividly how Nietzsche had spoken, on that day in summer of 1876, might have known the other basic thought that Nietzsche had, at that date, already published. And this thought relates to the per se conservative nature of connoisseurship: »[Die Kunstkenner] wollen nicht, dass das Große entsteht: Ihr Mittel ist zu sagen, »seht, das Große ist schon da!« <> sie handeln jedenfalls so, als ob ihr Wahlspruch wäre: Lasst die Toten die Lebendigen begraben.« * We see Schifflände ahead of of, the bridgehead would be to our right, and we would have to cross the street to walk up Blumenrain. But no, we have to stop and think. And after that we will have to take a detour. We have to walk the Drei-Königs-Weglein, because for one, with Heraclitus on our mind, we have to stay close to the waters, and for two: we have to think and must not end our walk that swifly. * Even if we do not fully agree with Nietzsche, his questioning (of connoisseurship, besides of praising it), raises some basic questions: how is connoisseurship dealing with the new? With Heraclitus we might say that, on the very bottom of things, there is nothing new, but on the level of different waters, there is also constant change. This by the way, might even apply as to the image of Heraclitus itself (and one may mention here that another Basel professor of philosophy has critized Nietzsche‘s image of Heraclitus). One might also ask whom Nietzsche has actually in mind, if speaking of connoisseurs (of art) that allegedly think that the greatest things have already been created. Is he thinking of the 19th century‘s general tendency, or is he thinking actually of Jacob Burckhardt (who is, invisibly, and as Scheffler’s other professor, also present at our walk)? But Nietzsche, who is also praising the ideal of being observant, of being careful (and appreciative) like a goldsmith, invites us only to think further, to differentiate various ways of connoisseurship. Those ways that are attentive as to the change, the new, the upcoming things. And those that are attentive, careful and observant in looking back. And one might apply this differentiation also to the individuals in connoisseurship and ask for example: did Roberto Longhi think that all great things had already been created? Longhi, the advocate of Futurism? And what about Giovanni Morelli and others. And we see that we have also to differentiate as to the individual age of the individual connoisseur, because, for example, Morelli showed very attentive as to contemporary art when being young, and lost that interest for the new to some degree, when coming of age. * |

On our right a fashion store, and now we have almost reached the bridgehead, where we have to cross the street to reach the Blumenrain (picture: DS).

Looking back once more (picture: DS)

| It is German Hip Hop that ends our musing. German Hip Hop that seems to be also very careful with words. I hear the word »Welle«, and they rhyme with »Das gibt es nicht bei Quelle«. We have passed a group of teenagers; he have also passed some members of the grand hotel’s staff, and we arrive now at Blumenrain, as it were, from the other side and just walk back to Schifflände. * The year of 1876 was, on some level, frustrating for Nietzsche, but he did travel to Italy, to stay with Malwida von Meysenbug, in the fall (which, yet later, ended with another desaster). In summer he had also corresponded with his friend Rohde (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erwin_Rohde), who was going to marry (and Nietzsche, who was declaring that he was not a poet, sent him a poem about a wanderer, all the same). He had also been thinking, as another letter to Rohde shows, on the Greek’s concepts of love between men and boys, and this on all levels (and Scheffler’s uneasiness with Nietzsche had obviously to do with feeling uneasy about what the philosophical eros, that was obviously present on some level, was all about, and where it would lead them to). Nevertheless it was Scheffler, who, in a way, excused for his suspicions, in portraying Nietzsche as a lecturer in retrospect, and in recalling that they had been united in their being stricken by words of the Pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus (as quoted in Greek and in German by Nietzsche, and thus as heard being quoted by Nietzsche’s voice). And it is also Scheffler, recalling how Nietzsche did speak of Heraclitus, who points us to the very core of connoisseurship, of knowing something, of knowing something well, because, in passing by, Scheffler also explains, why Nietzsche’s voice had been that impressive to him: because Nietzsche had spoken with inner participation (»innerer Anteilnahme«) of Heraclitus, the solitary. In other words (and with more pathos): Nietzsche had spoken from the bottom of his soul. And in that, indirectly and implicitly, Nietzsche did touch and evoke a third basic question as to connoisseurship: the question if not this inner participation is the very basis of all actual knowing, whatever branch of connoisseurship we may speak of, and in that the invariant nature of real connoisseurship, as opposed to the superficial knowing, to the merely suggestive appearing to know of the old or new, and, in very particular, as opposed to any ›dead knowledge‹ of things passed, be it in art or in the history of philosophy and learning. |

A jeweller’s shopwindow, somewhere in Basel (picture: DS)

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM  |

(Picture: DS)

Heraclitus, as imagined by Rubens

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS