M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

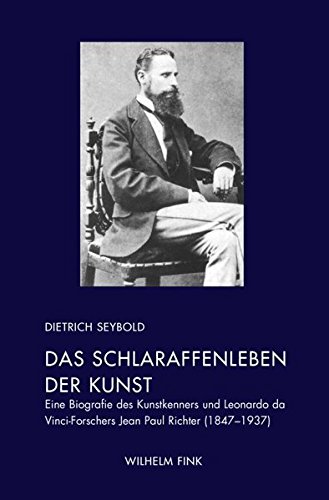

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

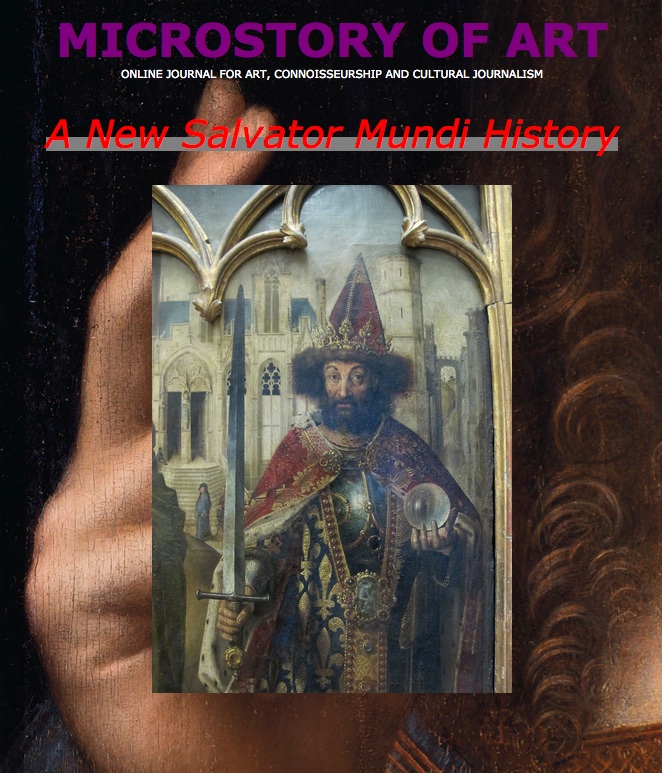

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Who Did Invent the Blue Hour? – An Interim Conclusion

(5.5.2022) Who did invent the concept, the notion of the ›blue hour‹ anyway? Artist Jan Fabre claimed that it had been his ancestor, entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre. But as soon as we have no definitive answer, we must stay cautious with that. Because what we are attempting here is to give an interim conclusion – by assembling, in a decidedly European perspective, artists, writers and – of course – also scientists, brief: people that are to be subsumed into the category of (creative) observers.

We had started our journey – embarking on a ›History of the Blue Hour‹ – which is nothing less than my personal cultural history, but also a cultural history of (usually hybrid) light, as well as a specific history of the blue hour phenomenon (the narrowing of perspective being the one conditon to embark on a history of light and its configurations in dusk and dawn anyway – we had started this journey, being aware that there is a rather timeless phenomenon of twilight – and that there is whatever creative observers have made of it. In the context of particular cultural configurations.

Let’s start roughly in the middle of the 19th century, let’s start with the blue hour in Jane Eyre, novel by English writer Charlotte Brontë, published in 1847:

»No sooner had twilight, that hour of romance, began to lower her blue and starry banner over the lattice, than I rose, opened the piano, and entreated him, for the love of heaven, to give me a song.« (p. 289 in the edition that I have at hand)

We do not encounter here the explicit naming of a ›blue hour‹, but what we have here (the context of the passage, as the content of the novel, is not of immediate interest to us here) is an interesting combination; which is why I’d like to start from this, taking the passage as a kind of compass to embark anew on our journey.

›Twilight, that hour of romance‹ – a German reader, choosing to read this novel in translation might encounter a translation like ›Dämmerung, Stunde der Romantik‹, which would leave him asking perhaps what exactly ›Romantik‹ might mean here; because it could mean to him, what in the English languange is referred to as ›Romanticism‹. Even more so, as the prominent configuration of blue, twilight, and romantic ideas of whatever kind, indeed culminating also in the concept of a ›blue hour‹ (but supposedly only later), cannot be separated from the period of Romanticism.

Let’s briefly look at some examples, one taken from the epistolary novel Hyperion by German poet Friedrich Hölderlin (1797/99):

»O Athen! rief Diotima; ich habe manchmal getrauert, wenn ich dahinaussah, und aus der blauen Dämmerung mir das Phantom des Olympion aufstieg!

Wie weit ists hinüber? fragt ich.

Eine Tagreise vielleicht, erwiderte Diotima.

Eine Tagreise, rief ich, und ich war noch nicht drüben? Wir müssen gleich hinüber zusammen.«

A longing for Athens, for Greece, is expressed here, as well as triggered anew, as one might say, by the naming of a phantom, by projecting of this phantom into the blue twilight: by evoking the Olympieion, the temple of the Olympian Zeus at Athens (for nocturnal picture see here).

(Picture: George E. Koronaios)

We might contrast this passage with a somewhat earlier example, taken from Ulrich Bräker, a Swiss writer who is not to be subsumed into the category of Romanticism. The passage is taken from his autobiography, having been published in 1789:

»Aber mir war schon oft, ich sey verzückt, wenn ich all’ diese Herrlichkeit überschaute, und so, in Gedanken vertieft, den Vollmond über mir, dieser Wiese entlang hin und hergieng; oder an einem schönen Sommerabend dort jenen Hügel bestieg – die Sonne sinken – die Schatten steigen sah – mein Häusgen schon in blauer Dämmerung stand, die schwirrenden Weste mich umsäuselten – die Vögel ihr sanftes Abendlied anhuben.«

The writer is contemplating the house he has ›built‹ (on the right), the existence he has created, and his whole life in the end, with his house seen in blue twilight during a summer’s evening. It is from the last chapter of his autobiography, and in some sense, a final, a conclusive impression (given in this context).

With a third example, taken from Georg Büchner’s Lenz novella (written in 1836, published posthumously in 1839), we may conclude that blue twilight, although none of these three writers is speaking explicitly of a ›blue hour‹, is common in pre-Romanticism, in Romanticism, as well as in Post-Romanticism. The passage – also a final impression from the very end of the novella – reads:

»Er sass mit kalter Resignation im Wagen, wie sie das Tal hervor nach Westen fuhren. Es war ihm einerlei, wohin man ihn führte. Mehrmals, wo der Wagen bei dem schlechten Wege in Gefahr geriet, blieb er ganz ruhig sitzen; er war vollkommen gleichgültig. In diesem Zustand legte er den Weg durchs Gebirg zurück. Gegen Abend waren sie im Rheintale. Sie entfernten sich allmählich vom Gebirg, das nun wie eine tiefblaue Kristallwelle sich in das Abendrot hob, und auf deren warmer Flut die roten Strahlen des Abends spielten; über die Ebene hin am Fuße des Gebirgs lag ein schimmerndes, bläuliches Gespinst.«

The landscape is that of the Vosges mountains (for an example see below).

(Picture: H. Schreiber)

***

Now we may turn more to the end of the 19th century, towards the notoriously famous fin-de-siècle.

As we already have seen (see my The Bue Hour Continued), French poet Arthur Rimbaud explicitly speaks of »heures bleues» – using the plural, which might confuse scientists, since the period of dusk and dawn usually is not that long –, in his poem Est-elle Almée?, written in »Juillet 1872«, but published apparently only in 1895 (it is the city of Brussels, evoked in twilight, here).

Since in 1890 we find also two painters, Max Klinger and Albert Besnard, painting a blue hour respectively (or naming, what they painted, after the blue hour, or inventing the concept on their own; I do not know the painting by Besnard), the chronology gets somewhat complicated. But not too complicated, since we have created a framework now, against which claims of certain people, of certain people having ›invented‹ the notion, can be tested. This framework might be concluded by naming the poem Blaue Stunde by German poet Stefan George, published in 1899.

It is not very likely, we now have to conclude, that entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre did invent the ›blue hour‹. Although being a fabulous writer in his own right, and although being someone being in touch with French poet Stéphane Mallarmé, and also influencing Belgian fin-de-siècle poetry as a writer in his own right, Fabre did publish his 10 volumes of most influential entomologist writing only after the before-mentioned poem by Rimbaud was written in 1872. It is still possible that earlier writings, his thesis for example, may contain the notion (or that Fabre invented the notion independently) – I do not know that, and as said, what I am doing here is meant to be an interim conclusion. It is also possible, of course, that the notion was ›invented‹ by many people, independently. But the claim that one particular writer, poet or scientist was indeed the first to speak of the ›blue hour‹, was the first to combine these two words in whatever European or Non-European language, has to be tested from now on. Against the chronology given here (on the right the Blaue Stunde by Max Klinger).

Further reading:

Angelika Overath, Das andere Blau. Zur Poetik einer Farbe im modernen Gedicht, Stuttgart 1987

Gabriele Sander (ed.), Blaue Gedichte, Stuttgart 2001

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS