M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Iconography of Sustainability 2  (new series) |

See also series 1

Aral Sea:

(20.6.2022) How does sustainability look like? – this is the question. Does it look like Soviet era fish cans in the Aral Sea Museum? Or does it look like the statue of a simple fisherman (also in the Aral Sea Museum)?

The Aral Sea – obviously – is a sea; but it is also a symbol and a cluster of stories. It is a symbol for ecological desaster (it already was in the early 1990s), but the reasons behind that desaster are complex; and the cluster of stories, stories about mismanagement, probably, yes, but also stories about great visions (industrialization; corrections of rivers; a blooming cotton industry, blooming due to irrigation), visions that proved to be impossible to attain, or to attain in full (and without producing desaster). Many people, in the past, had visions of a brighter future, and the interactions of many strategies of many actors (of various regions or, now, countries), it seems, produced an ecological desaster in the end and over time, a desaster that, again, many, today, are trying to turn into more modest, smaller, and probably local, success stories.

While looking into some more recent studies on the Aral Sea complex I have come across a book by William Wheeler (Environment and Post-Soviet Transformation in Kazakhstan’s Aral Sea Region. Sea Changes, 2021); and what I found remarkable about that book, is that the author is aware that Environemental History is an embattled field. The Aral Sea desaster cannot be explained by just blaming Soviet mismanagement, the problem is more complex. And does sustainability look like the fish cans now, or like the modest fisherman? There has always been a lot of change in the Aral Sea region. Visions of what it meant to secure a future had been different. And one should stay aware that also today, there is probably not one visions only, of what it means to secure a future.

(Pictures: Adam Harangozó)

Ark:

(23.5.2022) It is interesting to note that Leonardo da Vinci yet challenged the Biblical account on the deluge, but only to a certain degree. I have always felt that Leonardo is rather to be seen as a distant forerunner of those filmmakers, who do epic movies on Biblical subjects, and – while opting for cinematic realism, as overwhelming as possible – remain as cautious as already Leonardo had been, in that they question the ›realism‹ of the Biblical discourse to a certain degree, but seem to remain open for the idea that there could always be natural explanations for what the Bible seems – seems – to present as facts (compare for example the audio commentary of Ridley Scott concerning his movie Exodus: Gods and Kings, particularly as to the Red Sea-sequences).

Compared to the stance of Leonardo as well as that of modern filmakers, it seems to me that medieval art, in some respects, and also some early modern art is often more ›modern‹ than Leonardo, in that Biblical discourses are transmitted less ›naturalistic›, but more as tales or subjects with a decidedly symbolical content. And the symbolical content of the tale of the ark of Noah is, among other things, diversity of species and the question how to retain and protect such diversity. A son of Bruegel is displaying diversity (first example below). Further below we will give also an early modern still life that displays the specific diversity of cherries. And the sober, brilliant, precise and breathtaking discourse of medieval illustrations to the Beatus of Liébana commentary to the Book of Revelation – by a woman artist named En and others – can hardly be topped anyway (second example below).

Cherries:

(7.6.2022) The history of the still life does know many specializations. The still life that we see here, a fruit still life by Bartolomeo Bimbi (Il Blimbi), specializes even more: it specializes in types of cherries. By showing – and by even enlisting (on the pedestal) – what types of cherries did exist at the time the artist was active (the picture is dated: 1699). Thus art can act as a memory, an ecological memory, as to the history of types of fruits, and also of types that, perhaps do no longer exist, or are no longer being cultivated (Norbert Schneider, who highlighted the picture in an epoch-making still life exhibition catalogue; see further reading), even does refer to the specialized culture of orchards and to contemporary dictionaries; p. 282).

Environmental history and art history go hand in hand here, since the picture, from a formal point of view, does show variety within the specialization in cherries (unity). And we are asked, by the picture, to see that. Which, from another point of view, means nothing else than the picture is asking us, what we might think of variety in unity. Or of unity without variety, due to the disappearence of many historically recorded types of fruits.

Further reading: Norbert Schneider, Wirtschafts- und sozialgeschichtliche Aspekte des Früchtestillebens, in: Gerhard Langemeyer / Hans-Albert Peters (eds.), Stilleben in Europa, [exhibition catalogue] Münster/Baden-Baden 1979, p. 266-292

Conceptual Art:

(16.6.2022) In his Duration Piece #9 Douglas Huebler had documented the travels of a plastic box, sent from East Coast to West Coast, and back again, and back again. Postal receipts, indirectly, make visible the travels of an object, let’s say an object that may also represent a commodity, and these travels (also shown on a map), on a level of real life, seem rather pointless. On a level of art, however, such travels are not pointless, but make a metaphor; a metaphor for commodities travelling, without us being aware, all of the time, how many miles, for example a box of strawberries has travelled. Duration Piece #9 dates from 1969, and it certainly was not meant to be included in a visual essay on the iconography of sustainability in 2022. But it is to be included here: because Conceptual Art, conceptual artists like Douglas Huebler, have shown ways to make things, facts, visible; things, facts, that we can know of, but not necessarily have a visual representation of their own. And because the question of how and how far commodities travel is, in the context of ecological discussions, a most urgent question. Duration Piece #9 might not be an artwork that the art world of today is caring of. It seems to be largely forgotten. But it is not forgotten, and may not be forgotten, as long as art is expected to be ›relevant‹. Which is the case today, at least seemingly, but it may be that behind the discourse of ›relevance‹ is actually nothing real, nothing actually relevant – but only emptyness, covered by the illusions produced by the art world itself.

(Picture: taken from Constance M. Lewallen / Karen Moss, State of Mind. New California Art Circa 1970, 2011)

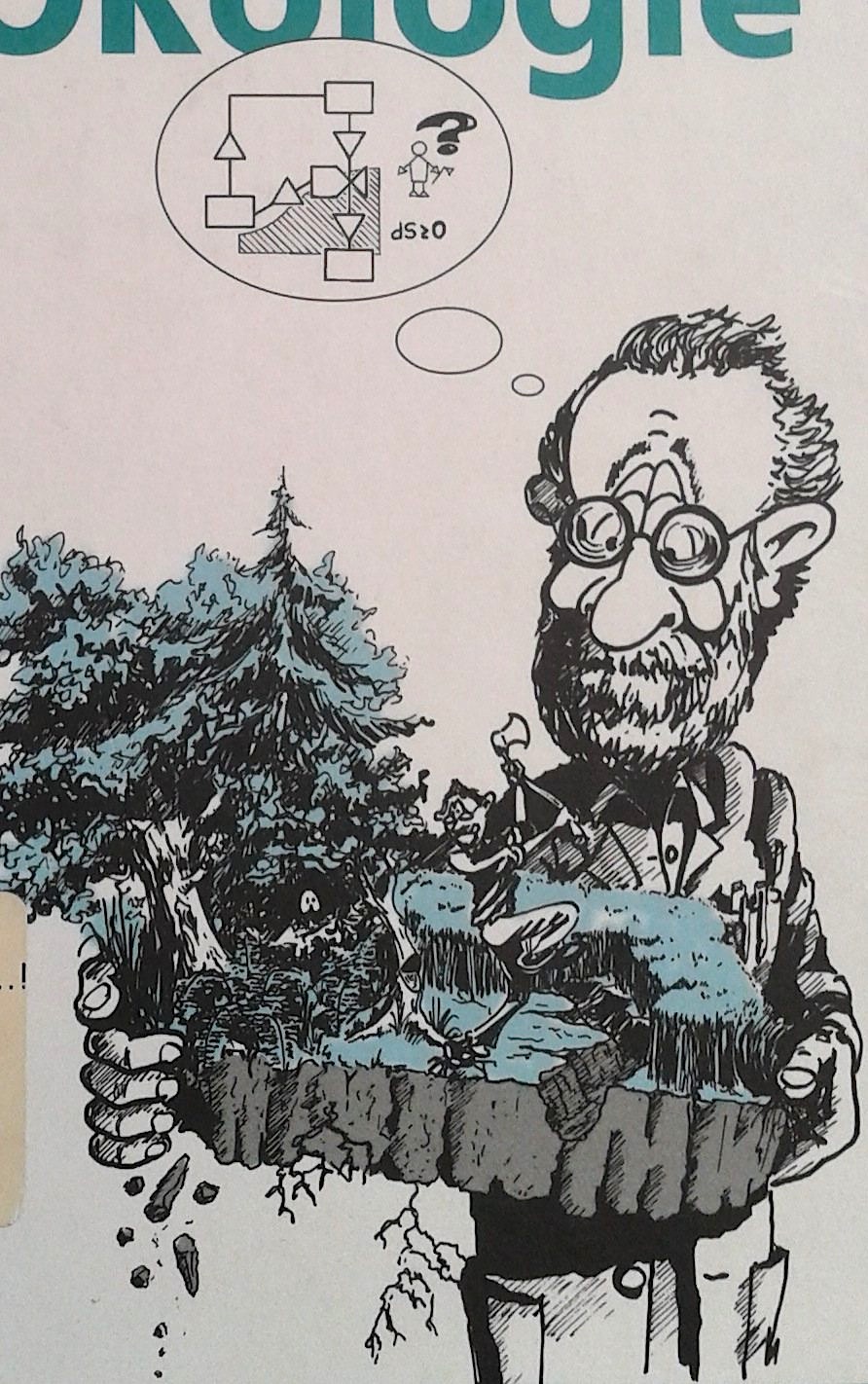

Diagram:

(Picture: from cover of Die Natur der Ökologie; cartoon by Karl Herweg, Bern)

(14.6.2022) Die Natur der Ökologie (›The Nature of Ecology‹) is the title of a book by Antonio Valsangiacomo, a book which was published in 1998 and deals with ecology, its nature and its ambitions. It is a book which is critical as to the concept of sustainability (›a concept for everything is a concept for nothing‹; see page 244) and reminds us, among other things, that there is also the concept of a carrying capacity, a concept which might be called more specific, more ›down-to-earth‹, than the concept of sustainability, which has turned, in the mean time, indeed into a rather empty anything-goes-formula.

The reason why I am including a reference to this book here, is the fact that its author had also a collegue, Karl Herweg, contribute cartoons to his book. And these cartoons deal with the problem that science means abstraction, and that also the science of ecology means abstraction. And the more abstract we get, the closer we get, on a visual level, to the visual world of diagrams, and – probably – the less attention the ecologist will get, because being precise means, at times, being complicated, so that in the end no one will listen anymore – despite the fact that, what the ecologist is talking about is very real, so real that everyone, actually, could relate to that real thing, which is nature, or at least a part of it.

All this is beautifully shown in one cartoon particularly, the one that I have chosen to show here. And we see, on a level of drawing and of artistic conepts, the concept of abstraction, the diagram, as well as the concept of realism. And if we look, critically, at the concept of sustainability again, we will realize, that we have to study both, an abstract iconography of diagrams, as well as an iconography of realism (see for example the Sweetwater Pond example below). Diagrams can be, at times, too simplified, or, at times, too demanding. Realism can be overwhelming, manipulative or too superficial. And to look critically at the iconography of sustainability means to stay aware of all of this: the imagery of sustainability is an imagery of abstraction as well as a (hyper-)realistic one, and we have to stay aware that all concepts have strengths and weaknesses that have to do with the nature of these artistic strategies.

Dimension of Time:

(19.6.2022) If ›sustainability‹ means ›aiming at securing a future (of something)‹, it is obvious that the dimension of time is crucial as to sustainability. And yet, it is the dimension of time that has been eliminated of (most superficial) re-conceptualizations of the notion (see also series one). This happened – it has to be researched in more detail – in the wake of the 1992 Earth Summit. The disneyfication of the term is a syndrome of the 1990s, as well as it is a phenomenon of the 21st century.

This means that we have to come back to the dimension of time, and this is what we do here. See: Future Sustainability; Present Sustainability; and Past Sustainability. Because humans are animals that are able to look back (at past experiences with sustainability, to reflect current developments and to project their conclusions into the future.

Future Sustainability:

(19.6.2022) Something that has not been reached yet is merely imaginary. ›The clock is ticking‹ on meeting the UN Sustainable Development goals‹ a UN deputy chief can be quoted (see here. It is obvious here that a dimension of time, as well as an imaginary component is inherent to any sustainability thinking, as far it is about the future (of something) that has to be secured. And it is probably this particular mix that makes the term attractive as well as rather vague (despite the notion of goal). And while the attractiveness of the notion of sustainability is seen, seemingly by anyone, the vagueness is not. Because otherwise one would have to question the scope of the Sustainability Development goals, as well as to discuss on what exact past experiences to draw, and on what conclusions to draw from that experiences. Any discussion on sustainability is also (if in a more hidden sense) a battle about interpreting the past. And the scope of the UN Sustainability Development goals is rather clouding the fact that any discussion on sustainability is also an encounter of conflicting visions as to how the (human) future is meant to look like.

Hunting/Fishing:

(24.5.2022) One of my favourite paintings by Picasso is his pittoresque Nightfishing at Antibes. Yet due to copyright restrictions I am not allowed to show that painting here (you can see it here. Instead we may look at this surprisingly brutal painting by Jean-François Millet, who, rather famous for his sowman or his praying peasants at sunset, gives a most brutal and nightmarish depiction of bird hunting at night, raising the question, if our view of hunting might be rather biased, since hunting might contribute to preserve animal populations in some cases, but excessive hunting, overhunting, might undermine sustainability as far as an animal population is concerned, endangering even its survival.

What exactly Millet is showing here, I don’t know, but it does remind me of Flaubert having written about most excessive and senseless hunting in his Legend of Saint Julian the Hospitalier (published three years after the 1874 painting by Millet). And the painting is also raising the question, if the rather pittoresque, seemingly well-humoured Picasso might be in fact as brutal as the scene depicted by Millet, only disguising something in fact brutal and nightmarish as being the scenery of an outdoor adventure, pittoresque and good fun for any observer, which, by the way, are not implied as in Millet, but in the picture and shown by the picture.

Lineage:

(20.6.2022) Is there a book in the Bible that teaches sustainability, in the more modern sense, as we understand the term here? Yes, there is. It is the Book of Ruth. Which has been referred to as a kind of novella – and it is a novella that transmits, despite its shortness, a lot about Social History of Ancient Israel. It is a novella about migration and about a friendship between two widows, but on the level of Social History, it is about how an agricultural society seeks to secure a future (by applying rules as to how farmland passes from one hand to the other), and apart from all that it is a novella that transmits also details as to how an agricultural society dealt with the problem of poverty, and with the problem of feeding the poor. And in the end: the Book of Ruth is about lineage too, which is a special kind of sustainability: families, mostly aristocratic families, are securing their respective future by marriage, by having (or producing) heirs. And thus societies have to think about how to organize that too. The Book of Ruth shows all that, and painters have shown aspects of all that, because, not to forget: the Book of Ruth, in the broader context (of the Bible), is about the lineage of King David, and thus about the lineage of Jesus Christ.

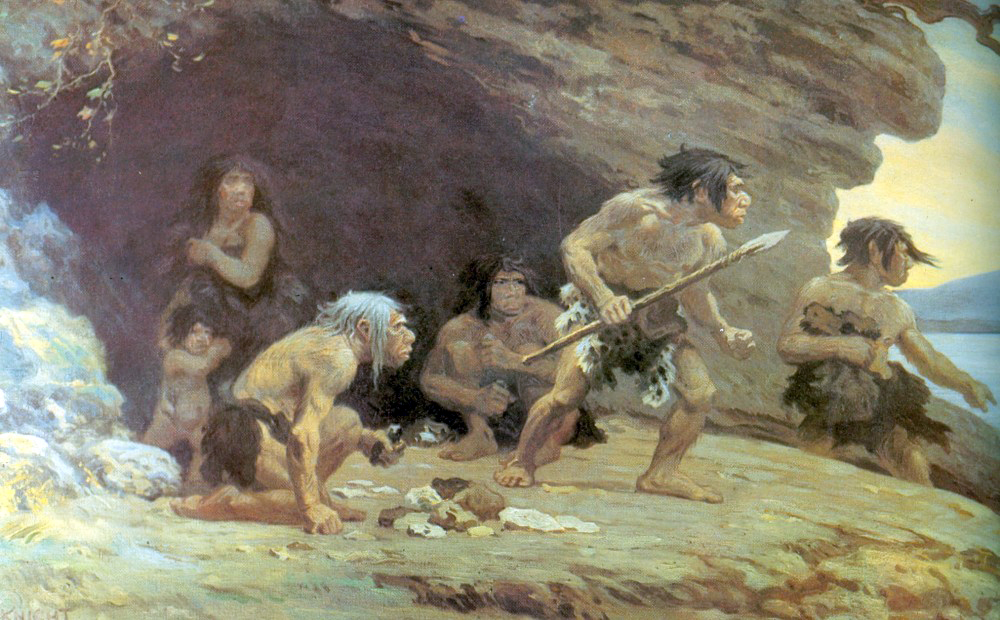

Longue-Durée Perspective:

(27.5.2022) Is there a role model as to a sustainable way of living? Perhaps not only one, but one seems to be the Neanderthals. Because with our antecendents, with the antecendents of modern humans, overhunting started. And big game was extinguished whereever modern humans appeared. Whereas Neanderthals did not extinguish the mammoth (perhaps because Neanderthals weren’t capable to do so). Brief: Modern humans showed to be the more efficient hunters, killers. At least this is the perspective of Johannes Krause and Thomas Trappe, in their book Hybris. Die Reise der Menschen zwischen Aufbruch und Scheitern, Berlin 2021, p. 93). Neanderthals, thus, may have laid the foundations of sustainability thinking, perhaps not their thinking, but our thinking, with our recalling of Neanderthalian ways of living.

(Illustration: Charles R. Knight)

Noble Savage:

(14.6.2022) It was shortly before the turn of the millennium. The myth of the noble savage got questioned (see for example here). Which means that one particular idea got questioned. And that idea was and is the idea that Native-Americans had lived in harmony with nature only. Thus one might say that it was the myth of the always and everywhere ecologically-correct Native-American that got questioned. In a book by Shepard Krech, for example. And this controversy is far from being over. It has also inscribed itself into the Encyclopedia of World Environmental History (see below). And one focus of that debate was the nature of bison hunt. Was there overhunting? Had Native-Americans whole herds of bisons die by having them jump into abysses, so that many more animals than necessary had to die? This is not to be answered here, but we have to note that the myth of the noble savage is also the product of images, and produces further images. And if the idea is to be questioned, the imagery has to be questioned as well. What images do we have of bison hunt?, we have to ask. And: do these images carry a myth, or are these images transmitting a truth? Because, if not, we might be manipulated by such images, and being misled, in our search for true images of sustainability.

(Indians hunting the bison by Karl Bodmer)

Past Sustainability:

(19.6.2022) Environmental history is as embattled as any branch of history (see for example Aral Sea above). It is perhaps not obvious to anyone, but the vision of what humans are and what humans will be in the future, is depending on past experiences. And such experiences have to be interpreted. It is not the past itself telling us what humans are, it is humans interpreting the past (with humans delving into History Wars on anything). See also: Noble Savage; Longue-Durée Perspective.

Present Sustainability:

(19.6.2022) If the present time can be thought of as a point in a continuum, present sustainability does not mean more than: there is continuity. Because: we still seem to exist.

Since there are many reasons to worry about continuity (of something), there is the concept of sustainability, meant to remind us not to overstretch the carrying-capacity of something we live on, given that we want continuity. But this means to navigate in time: it means to look back and to ask: what have we done right in the past for us to reach where we are now; and it means to ask: what do we have to do to further secure what we don’t want to give up. This said: the notion of sustainability cannot be thought as a harmony pill, since there is conflict lurking everywhere in these questions (what do we want to keep at all? and why? and who is ›we‹ at all?). And a sustainability discourse that has become an instrument of wellbeing, cannot be an honest sustainability discourse at all.

Rainfilled Suitcase:

(24.5.2022) What Jeff Wall has brilliantly shown in his 2001 Rainfilled Suitcase still life is the dissolution of human existence, while the materials that once – however ephemerally – made that existence still persist, perhaps on a way towards dissolution as well (tickets, paper, textiles), perhaps not (plastic).

Perhaps it was one existence, perhaps several existences – we don’t know exactly, and while there are some clues as to the nature of particular existence(s) (tickets; packages for pills?), it seems that the artist rather deliberately left these clues to be rather unspecific.

We see sustainability as well as unsustainability here, in its tragic – and also paradoxical dimensions. Plastic was once famed for durabilité – for it was meant to persist, which might be called a sort of sustainability no longer sought after, since this durabilité is polluting the oceans and beaches and so on.

And we see the remains, in a coffin-like structure, of human existence that – obviously – was not meant to be conserved. Litter may have been added to things that once had been put into that suitcase, and rain water soaked what was rather not meant to be soaked.

And one may think of migration here, migration that perhaps led to a better life, perhaps not. We don’t know the story of those human beings whose remains of personal belongings are dissolving in front of our eyes (as well as persisting) here. Was the life story behind what is still visible a tragic, brutal one? Did things, at least to some degree and for some, turn out well? What we see does not instigate optimism. But perhaps it is necessary to be reminded of how fragile any sustainability, on human, on personal level, may be. Another artist, Olafur Eliasson, who may be associated by many with the quest for sustainability, in conversation with Hans-Ulrich Obrist has referred to sustainability as something that also any human subject has to care for. Identity is not something to be taken for granted. Which leaves also the possibility of a more optimistic reading of Wall’s still life: identity, personal existence may also change, be changed, and also (and also felt by human beings) for the better.

(Picture: artblart.com)

Satellite:

(18.6.2022) Since the 16th Sustainable Development Goal of the UN is about ›peace, justice and strong institutions‹, it is now, among experts, being discussed if weapons (and investments into the respective industry) can be regarded as being in accordance with sustainability. Brief: even the layman can see that the discussion about sustainability has become too broad in scope, too unspecific and therefore rather empty, not to mention: opportunistic (since the layman could see this all, and also before February 24 2022).

And since everything is now, in some sense or other, in accordance with sustainability, even a satellite can be: the German satellite named Enmap, meant to research climate change and the environment in general, is brought into space by a SpaceX rocket, whose first stage is meant to return to earth and later will be re-used. This kind of sustainability, one has said, does fit an Unweltsatellit such as Enmap (see NZZ, 2.4.2022, p. 55).

(Pictures: enmap.org)

Shoes (sustainability in Van Gogh):

(26.5.2022) Yesterday I strolled around in the city. Oh, how my feet do hurt today. While strolling around I had mused about a lot of things. About a failed friendship in my youth, for example. About the changes the pandemic brought about, as far as the face of the city is concerned. Oh, and the consumer sentiment doesn’t seem to be good. 70% discount on everything (designer fashion). On the other hand a street artist with a laptop. Beggers have largely disappeared, as it seems (new rules). And in one neighborhood I spotted a new second hand store (clothes as well as bikes), ›use it twice‹ seems to be the motto. Oh, how I do love second hand stores!

Today I am thinking about shoes. What about to buy new ones in a second hand store? Old ones seem to be weared out. And now we are at the heart of the matter: are they still good enough to give them away, to throw them into a beforementioned recycling bin (with the postcard shot of the Matterhorn on it, to enhance the sublime feeling of giving one’s old shoes away)?

Could one imagine Vincent van Gogh throwing a pair of old shoes into a recycling bin? Why not? He is said to have bought a pair of shoes at a flea market (with intention to paint them, as it seems, but he had to further wear them out, apparently, for them to match his pre-conceived idea of old shoes – compare my theses on still lifes, below). And for one of his shoe still lifes he did apparently re-use a canvas. It showed a view of his brother’s apartment, but he did repaint that view, hailing the motto of ›use it twice‹.

If Vincent van Gogh indeed had bought a pair of shoes at a Parisian flee market, it is perhaps not very likely that these shoes are peasant shoes indeed. But the philosopher’s views on art (in this case: Martin Heidegger’s views) never have interested me much. What is interesting in the still life that I am showing here, is that we are meant to look at a sole, as well as at the upper part of one shoe, and one could indeed become a philosopher, thinking about that. If our reality only does float on an abyss of nothingness, as one might say, it might still good to have robust soles. And if we can rely on that, we can also turn our eyes to other inner-wordly things, such as the upper part, seen by people, and also by the walking person himself. Be it as it may, this still life of 1887 enriches our critical discourse on sustainability: it raises the question of how Vincent van Gogh might have thought about the concept of sustainability. He does not tell us. But he does show us pairs of old shoes. And his actions speak louder than words: in that he did, occasionally, re-use a canvas, to do exactly that. Showing us pairs of old, perhaps even Parisian, shoes. Which is inspiring me to say: no, Vincent van Gogh would not have thrown his shoes away, or thrown them into a recycling bin. He would have had them fixed (paying with a painting for that). And he would have used his shoes as long as possible.

Spargroschen:

(16.6.2022) Who’s in control of the money? The man. Who’s the drinker? Perhaps the man as well. But the painting is ambiguous. To lay money back during good times results in a Spargroschen, which is to be translated as a ›a bit of money, saved for dire circumstances‹. Sustainability has to be taken care of, but who does it? This is the question this painting is about. Is the woman the drinker, but under control of the man? Probabaly not a correct reading, probably not a politically-correct reading. Because the painting remains ambiguous. It is asking the question of who does what. And in the end this question is more important than a specific truth in or behind this particular painting by Wilhelm Leibl.

Still Lifes:

Picture: paintingstar.com ; Igor Grabar, Flowers and Fruit on the Piano

(26.5.2022) Neither painting nor the genre of the still life are dead. What can be referred to as moribund, are art historical conventions. Such as the coffee-table book. Such as the upper-class, bourgeois coffeetable book on still lifes. Or portraits. And also narrowminded ways of contemplating the still life. Because – what could be more boring that a history of the still life. Which would be lacking any specific perspective on that genre, presenting – to a bourgeois audience – largely nourishment to the eye for superficial consumption. The still life can be about so much more.

Here is a new perspective on the still life. A perspective that combines an interest in still lifes with an interest in the discourse on sustainability. In other words: one might combine environmental history, the history of consumption, the history of the economy – with the art history of the still life. And this would not be a history, interested merely in materialistic aspects. Not at all. This would be a history combining philosophical and historical and art historical perspectives. And here is a way to start: with only three theses.

1) The still life is about contemplating the world of natural and cultural objects. It is contemplation, as well as it shows or displays contemplation, and thus offers – perhaps unintentionally – a perspective on contemplation of objects, and the relation humans have with objects. The still life is about our relation we have with things.

2) Since the genre of the still life indeed – and over time – makes a history of the still life, one dimension of such history is obviously social history. Since we see frugality, we see luxury, we see poverty, we see ostentatious, debaucherous consumption. And of course we also see still lifes that are not obviously displaying any interest in social history or the history of consumption. Which is not to say that such pictures might not have a place in such a history. On the contrary. Senseless consumption (also of pictures) has its place in a (critical) history of consumption. A crucial place.

3) Theses one and two combined make an awareness what still lifes can do. And on the basis of such awareness artists can stage and have staged relations of humans with objects. Which means: the still life can build on such awareness what the still life can do, and go one step further. Becoming a more reflected comtemplation of how humans surround themselves with objects, in senseless or meaningful ways. Thus the still life can also be a stage or a laboratory, on which or in which the relations that humans have with things are more actively researched, imagined, corrected, questioned and so on.

(Picture: artnet.com)

And here is the example of a still life that may illustrate what a history of still lifes, focussing on the discourse of sustainability, could be:

In 1970 Neil Jenney painted his Litter and Bin still life. It is the picture of a trash bin, with litter placed next to the bin. A familiar sight in real life (especially during the pandemic), such picture raises numerous questions as to our relation with objects. Simple questions such as: why not putting the litter into the bin? Or: who are these people who place their litter next to the bin, and not into the bin?

Or more philosophical questions: since perhaps the definition of something as litter had turned out not to be as easy as someone had thought. Perhaps the painting is also about contemplating the difficulty of giving something away. With ›giving away‹ meaning: defining something as trash that, on a human level, perhaps also had been precious (for some time), defining something that had been precious as something meant to end up in a trash bin – now. So the litter placed next to the bin would actually show an unwillingness to depart with something precious, and it would also display – perhaps – a melancholy – in view of the passing of time and the changes time had brought.

Other examples (Jeff Wall, Rainfilled Suitcase) we discuss in separate paragraphs here, but it is noteworthy that Neil Jenney got the label of ›Bad Painting‹ from art history, is associated with that label (which he is said to have accepted), while a great deal of still lifes have actually been about showing how good someone is at painting, technically. But our history of the still life would not be about admiration of technical skills in the first place. It might also be about admiration, here and there, but admiration of mere technical skills could also get in the way of seeing what a simple, direct and intelligent picture such as Litter and Bin can be about as well.

Sweetwater Pond:

(14.6.2022) A documentary on the consequences of climate change in Southeast Asia. The Mekong Delta faces a drought, but it turns out, after a while, that the crisis which is described in this documentary is not only the consequence of climate change. No, it is also the consequence of not caring for sustainability on a local level. Because after a while, and rather marginally (since the narrative ›cannot‹ undermine itself, and it is a narrative about the consequences of climate change), the viewer is informed that local farmers have neglected to care for sweetwater ponds, while investing into water-intensive trees, because with fruits from these trees, one could earn more money.

The symbol of sustainability, thus and in the context of this crisis, is the sweetwater pond that catches rain water, which can be used for irrigation during a drought. And this is what we are showing here, more aware than before, that not everything is the consequence of climate change. The idea of sustainability had its local expressions, and one such expression was the sweetwater pond. Many households had it. But it got neglected.

(Picture: youtube.com ; arte)

Switzerland:

(27.5.2022) »Until the 1950s Swiss society still lived widely according to the principles of sustainability.« A quote from the Encyclopedia of World Environmental History, which was edited in 2004 by Shepard Krech III, J.R. McNeill and Carolyn Merchant. This is interesting in a number of ways. First of all: the article on Switzerland (in volume three) was done by Christian Pfister; and I do recall that, when being a student of history in the 1990s, I once saw the offer for a PhD grant in climate history at Bern at a notice board in Basel, and I do recall that, at the time, this seemed to be quite an exotic idea to work in that field, in that niche of history. But Environmental history (which did exist at Basel, in the aftermath of Schweizerhalle, it did prosper), Climate History – these fields did develop, and in 2004 an Encyclopedia of World Environmental History was published, including an article on Switzerland by Christian Pfister.

And the 1950s, yes, the era of the washing machine coming up (to name this device as a symbol), as well as the car ralley in the mountains and other things (I am studying the 1950s due to my upcoming publications on Picasso; and Picasso bought a washing machine as well, which was stared at like a marvel at his villa La Californie at Cannes…). A museum of the washing machine seems to exist in Mineral Wells, Texas (see picture below). And here is a link to the Museum of Washing Machines in Art.

(Picture: Michael Barera)

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Iconography of Sustainability  |

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS