M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

Dedicated to Werner Herzog

(Picture: DS)

That Bavarian filmmaker Werner Herzog (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Werner_Herzog) does warmly recommend reading to his film students is one thing – Herzog also seems to consider his writings as being rather more important than his films. Be this as it may, but I have always been fascinated by what Werner Herzog has said repeatedly on camera, respectively on a DVD audiocommentary track: namely that his 1972 film Aguirre, the Wrath of God (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aguirre,_the_Wrath_of_God), has been, originally, inspired, and that the intuition to actually make that film (in early 1972), has, originally, been triggered by browsing through a book for twelve-year-old readers, a book on explorers and adventurers that Herzog, accidentally, got in his hands when he, early in 1971, was staying at a friend’s place.

Many myths on Herzog do exist, and in many a myth or rumor a grain of truth might also be hidden (personally I do like the story that Herzog, while travelling, spent the night in houses that he broke in, and that he finished some crossword puzzles lying around in such week end houses). And the following is my finishing of a crossword puzzle. An exploration into the mythic ›microstory‹ of a book for twelve-year-old readers, and of few lines within that book, that had had this mighty impact on Herzog, and we ask: does this book actually exist (no one, as far as we can see, has yet identified this book)? Or is the book itself a myth, and the story fully invented? But why inventing such a story, and why giving such importance to a book? And why inventing such a story, if the story can be investigated? In sum, this is a myth worth studying, a Werner Herzog story worthy to be explored. And here is what while exploring – here is what we saw and found (sidehead picture: littelwhitelies.co.uk).

The Book For Young Readers That Inspired Aguirre, the Wrath of God

A worthy beginning might be this: we are snowbound.

Which is actually the truth, or becoming more and more true with every hour. Christmas days have passed, and the year of 2014 is coming to an end. And what to do, if we are actually snowbound? Well, we’ll watch, again, the 1978 Werner Herzog portrait called Was ich bin, sind meine Filme (I Am My Films). Because this is where to start with our exploration. Because in this very documentary wherein the Bavarian filmmaker is being asked when, as for the idea, the film Aguirre did originate. And this is what Werner Herzog, in c. 1976 (and at about 1:04 within the documentary, after explaining that Aguirre was being shot at the beginning of 1972), did say (my transcription and translation):

(Picture/source: Was ich bin, sind meine Filme)

»Ja, a Jahr vorher etwa, also Anfang ’71. Da hab ich bei einem Freund mal so geblättert, bisschen, in einem Buch so für Zwölfjährige. So über Entdeckungen, also über Kolumbus und Magellan und Alexander den Grossen und Amundsen, und da war eben, vielleicht zehn, fünfzehn Zeilen über einen Mann namens Aguirre drin, der sich also in so einer Expedition selbständig gemacht hat und die Macht an sich riss, und dann mit ein paar halbverhungerten Leuten das Spanische Königshaus für aller Rechte verlustig erklärt hat und einen eigenen Mann zum Kaiser gekrönt hat. Das hat mich eben sehr fasziniert und ich wusste schlagartig, das wäre der nächste Film, den ich zu machen hab.«

(›Well, about a year earlier, that is at the beginning of ’71. I did browse a little then, sort of, in a book for about twelve-year-olds, at a friend’s place. A book about discoveries, that is about Columbus and Magellan and Alexander the Great and Amundsen, and there were (was), maybe ten, fifteen lines, about a man named Aguirre who went freelance in such an expedition, and seized power, and then did declare the Spanish Crown for being perempted of all rights, and did crown an own man as the emperor. This did simply fascinate me tremendously, and I knew abruptly that this would be the next film that I had to make.‹)

*

With this we got a few clues to work with: a book for about twelve-year-olds. Published earlier than 1971. With sections on Columbus, Magellan, Alexander the Great and Amundsen. And, maybe ten, fifteen lines on Lope de Aguirre, a man, than does not figure in a great many books on famous explorers or travellers, this apparently rather crazy-evil man, a footnote of history (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lope_de_Aguirre), but of legendary malice, if not to say mad malice. At least not in a many books actually meant for young readers. But nevertheless: does such a book exist?

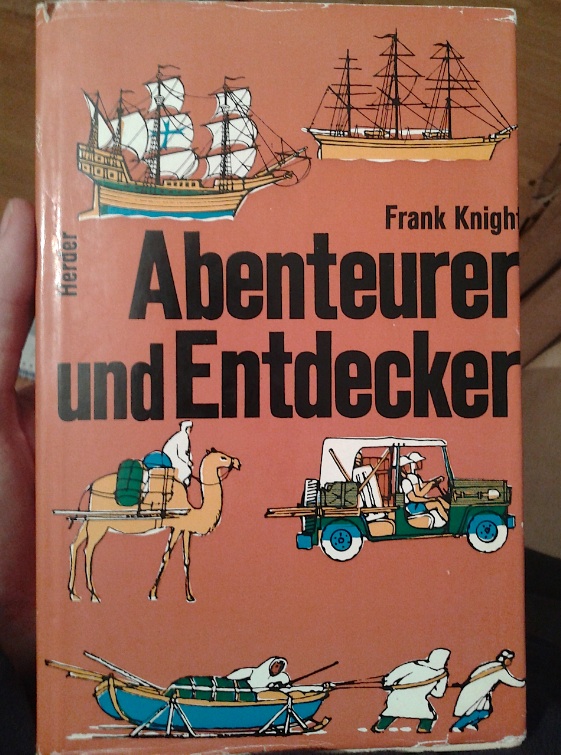

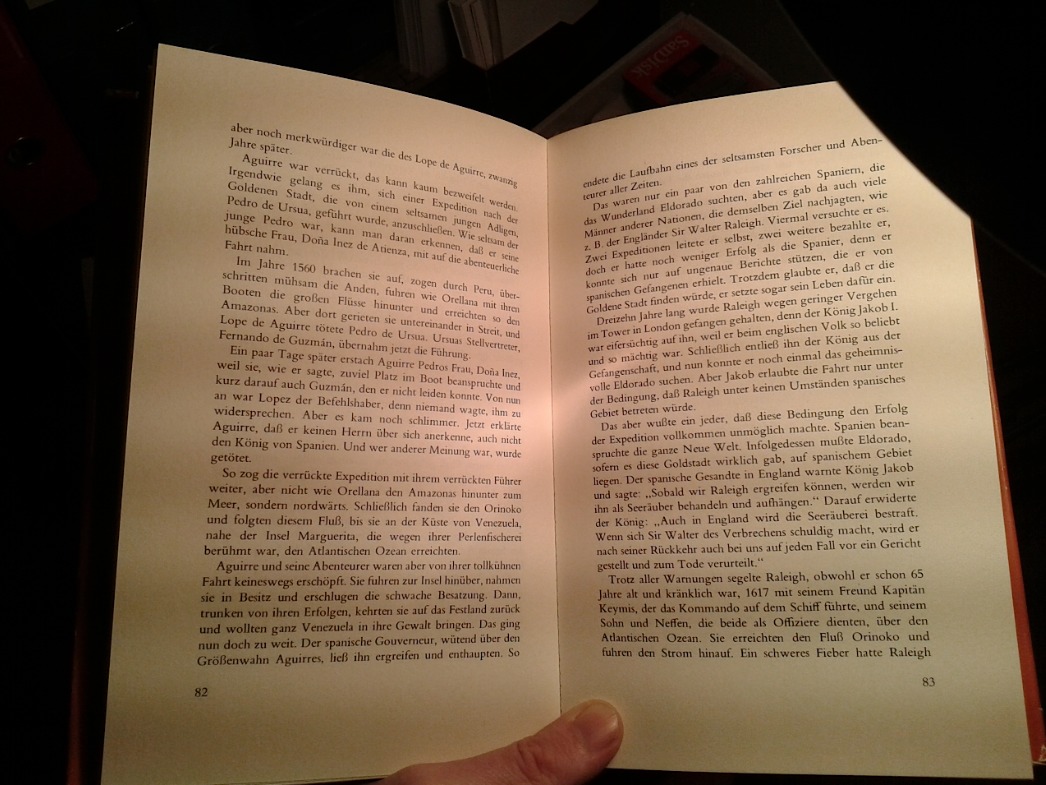

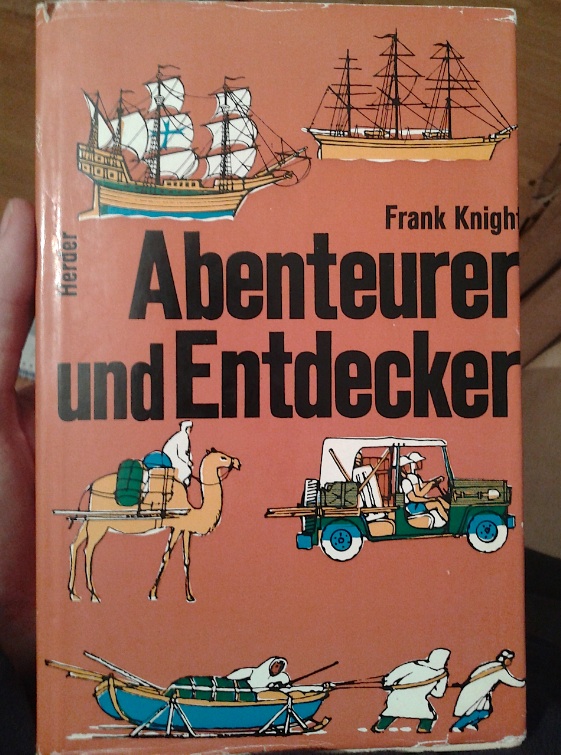

It does. After having browsed the large library of our empty week end house (we still are snowbound) we found a book that matches the description. This must be, or most likely is it: Frank Knight, Abenteurer und Entdecker, published in 1969, a book that is actually made of two books that originally were published in English in 1964 and 1965: Stories of Famous Explorers by Sea and Stories of Famous Explorers by Land). This is the one book that passes the test. That has sections on all the explorers named. And, most important, this is the one book that passes the ›Aguirre test‹. Except: It has quite precisely one page on Lope the Aguirre, and not ›maybe ten, fifteen lines‹. All in all I would say: this is most likely it, the book for young readers that inspired Aguirre, the Wrath of God. It is, by the way, by an English writer (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Knight_%28author%29), who probably never got to know that this one book of his had had this impact on Werner Herzog (and indirectly and subsequently on filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Ford_Coppola) and films like Apocalypse Now).

(Picture: DS)

A little snowbound (picture: DS)

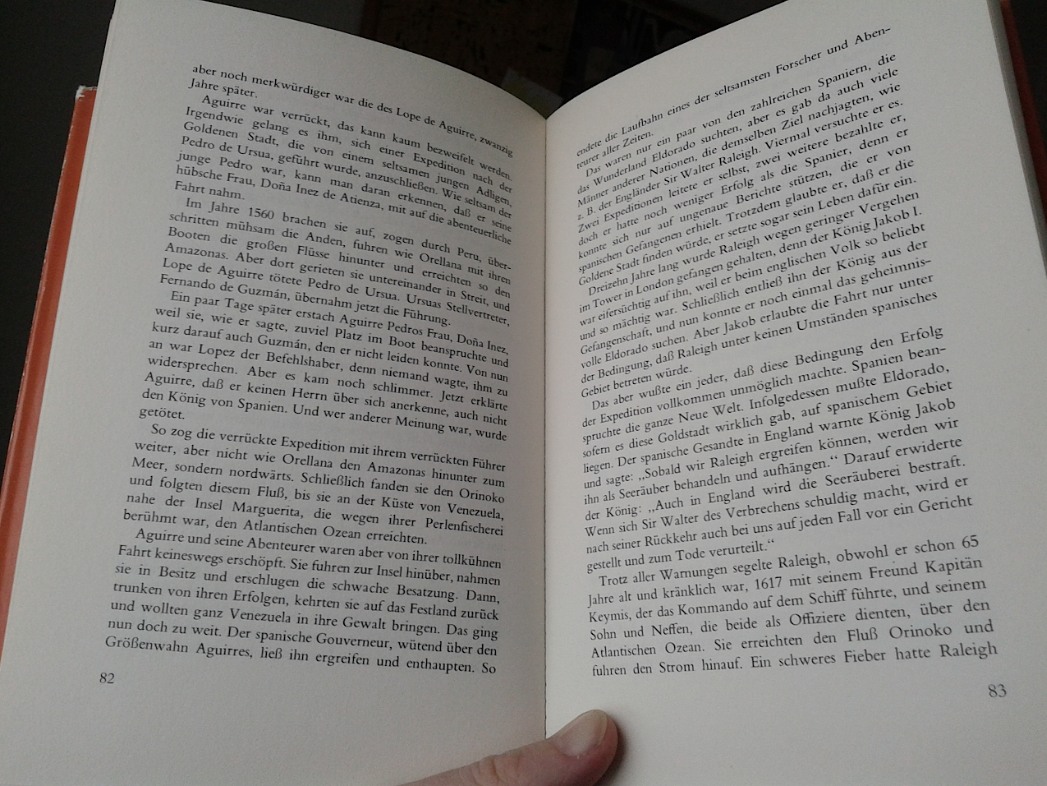

And now that we are really snowbound – we may dream of Eldorado. What better way might there be to dream of Eldorado? Inspired by the one small chapter entitled Eldorado, die goldene Stadt (p. 79ff.) that includes the one page on Lope de Aguirre (p. 82). And we imagine 28-year-old Werner Herzog, at a friend’s place at the beginning of 1971, and reading this chapter with us. What kind of Aguirre is presented here? What Aguirre is presented to us all?

Well, let us first take a step back (and at the same time a step forward), because the chapter on Eldorado has all the motifs that also the film Aguirre has become famous for, and I mean visual motifs. The motifs that Werner Herzog found visual expressions for: namely the motif of the descent from high mountains into the Amazon basin, the descent from highest mountains into the jungle. And also the motif of the journey on the river, resulting in dissolution of order and in desaster (but this is actually the story of Francisco de Orellana (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_de_Orellana), discovering the river that, because of the ›Amazons› (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazons) has become known to us as Amazon). These motifs mingle in the chapter, and mingle in our mind, be it that we are twelve-year-old readers or be it that we are adults (and I must say that, in January of 1971, I was not even being born).

What Aguirre is this that Frank Knight immediately introduces to us as being crazy? (Or as ›mad‹, or ›insane‹; what I did order from a antiquarian bookseller via Amazon was the 1969 German book; the book arrived right after Christmas, but of course I do not know what exact words Frank Knight originally did use). The Aguirre that Werner Herzog, at the beginning of 1971, was introduced to was ›verrückt‹ (p. 82 »Aguirre war verrückt, das kann kaum bezweifelt werden.»; ›Aguirre was crazy, there can hardly be a doubt about that.‹). And to sum up the one page on this madman Aguirre, I would say that this is about a man that managed to get aboard of a ship (an expedition), and that managed to take over that ship, to go even farther, which is, to dismiss an established order of things, an established world order, to declare his own new world order, which in the end of the film, the legend and, not to be forgotten, also the history, results with his own downfall.

(Picture: DS)

(Pictures: imgarcade.com; golgelervetoz.blogspot.com; bg picture: DS)  |

(Picture: Was ich bin, sind meine Filme)

(Picture: Was ich bin, sind meine Filme)

Directing Landscapes

Is it with a grain of salt that Werner Herzog says: ›Landscape, you got no choice‹? Which means that his inner vision of a particular film is not to be negociated. And landscapes as well as animals, according to Herzog, can be staged. In other words: it’s not the landscape, not the ›location‹, if one likes so, that decides over the visual outlook of a particular film. It’s, according to that, the inner vision of the film’s director. But the inner vision, one might add now, after the above said, is not absolute, is not free, but influenced by words, by reading. And also by maps. Another organizing, arousing influence. On a filmmaker’s imagination that is ready to be aroused. By words invoking images and landscapes to be concocted. Or as Herzog, again in Was ich bin, sind meine Filme, puts it:

»Von Landkarten her seh ich schon viel. Ich hab da ein ganz starkes Gespür dann auch von Landkarten her für Landschaften entwickelt. Da vertu’ ich mich auch selten. Nur: Ich hab das im Drehbuch so genau beschrieben, den Urwald und so. Dass ich… Ich hab das so intensiv mir vorgestellt auch, dass ich gedacht hab: Dem Land lässt Du keine Wahl, es muss so sein wie beschrieben. Und es war so wie beschrieben.

Ich glaub also auch an Inszenierbarkeit von Landschaften, ich glaub an Inszenierbarkeit von Tieren. […]«

(›Due to maps I can already see much. Moreover I happen to have developed also an utterly strong sensitivity for landscapes, due to maps. In this respect I also rarely get it wrong. However: In the screenplay I did describe this that precisely, the jungle and all that. That I… I did also imagine this that intensely, that I have thought: You leave no choice to the land, it’ll got to be as it is described. And it was as (it was) described.‹)

Why not believing this to some degree (we also know from a recent Werner Herzog biography that the Herzog boys did watch Tarzan movies when being boys). And we do also know that much of what Werner Herzog says has to be taken with a grain of salt. Listen, for example to the audiocommentary track of the Aguirre DVD of 2006, listen to Herzog recalling that it was in the rain season that Aguirre was being shot, that the jungle was swamped for miles at this particular moment in time, and listen to him saying and referring to his movie at the same time: ›und so sah das eben aus!‹ (›this is how it simply looked like‹).

Does this sound like a director staging a landscape, a landscape that hasn’t got a choice? But Werner Herzog did not do nothing. He did react to the landscape acting, to the landscape that he did direct. By inventing another scene of men building another raft, and of the conflict resulting thereof.

Werner Herzog art works have become complex conglomerates wherein, today more than in 1972, many things do mingle: a physical experience of making these films (and the narratives evolving from these experiences), but also texts, and also concepts (for example of opposing very static tableau-like scenes with ecstatic and very physical scenes), not to speak of the actual images. We can speak of landscapes acting and being staged, and of animals acting and being staged (Herzog does also say that a particular scene with mice could actually not be produced at all; that, in other words, some ingredients of these films are rather to be seen as gifts from somewhere, and this applies also to the one scene with a butterfly resting on one actor’s shoulder, and probably also to the final sequence with the monkeys on a raft): the story being told, the history that the story being told is more or less based on, and, thirdly, the various stories of the making of these films are the three basic dimensions that mingle here.

In more recent films Werner Herzog more obviously did travel with, or better: in the footsteps of certain people as for example the late Timothy Treadwell (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timothy_Treadwell), which means that Herzog not only did travel but also commented on and reflected upon these particular journeys – in his films. And most important: using also footage whose actual author had been ›Grizzly Man‹ Timothy Treadwell himself (with himself, with landscapes and with animals, sometimes accidentally, appearing in this very footage). But in some way this structure can already be found in, is already foreshadowed by Aguirre of 1972. Because for Aguirre Herzog invented a ficticious diary by a historic monk named Gaspar de Carvajal that he used as his narrative frame (thus Carvajal was, in some way, the traveller Herzog travelled with in 1971/72). And here, we’ve come full circle, we can come back to Francisco de Orellana, and to the Eldorado chapter of Frank Knight’s book that we do consider as the original inspiration for Aguirre: because this monk named Carvajal was member of Orellana’s expedition that embarked to explore the Amazon, and the chapter of Frank Knight’s book does, just before telling us something about crazy Aguirre, about this very expedition (actual Amazons, however, do only figure in another Herzog).

Finally: a Mythic Scene

Probably any cinephile might be able to recall the final sequence of Aguirre, the Wrath of God. The raft, the physical movement of the camera eye, the circling movement of the camera, encircling the raft, the river, the suggestive music, the dark-green forest margins, the monkeys on the raft, moving clusters of little monkeys, and finally: a leading actor, tumbling, an actor that, as we seem to know today, did actually rather belong in prison.

This might be one magic moment of cinema, one mythic scene. But we think now of another mythic scene, and we do cut:

To the very beginning of 1971. Maybe it is early in January, maybe the scenery is Munich, and maybe there is snow. And as we know, and this we seem to know for certain, Werner Herzog is going to visit a friend. Maybe it was Florian Fricke, or maybe it was Wolfgang von Ungern-Sternberg, and when Herzog came to his friend’s place, his friend was apparently very busy on the phone (the source for this is, again, the Aguirre audiocommentary track). And Werner Herzog could hardly greet his friend, being so busy making phone calls, and keeping on speaking to another person on the phone. Maybe his friend, while speaking, made a pointing gesture, pointing to his living room, or pointing to his library, inviting his friend to make himself comfortable in the meantime.

And while we see Werner Herzog now waiting for his friend to end his call, and while, maybe, we see him listen, with one ear, to his friend speaking to another person on the phone – we suddenly see him taking a look at the books in his friend’s library. – – –

It seems that this was not the only time that Werner Herzog did invite chance, that he did allow chance to decide with him over what would be his next project or film (a similar story does exist as to the film Lebenszeichen; see Moritz Holfelder, Werner Herzog, p. 47). And why not consider this as the actual, or at least as one rather unknown, but certainly as another mythic scene: Werner Herzog’s grasping of a, his browsing of a book for twelve-year-olds, or maybe (as he says on the DVD audiocommentary track, recorded in about 2005) a book for › about thirteen- or fourteen-year-olds‹: the one book that he had inspire, the one chance that he had help to decide, at the beginning of 1971, over his next project.

And we finish with saying that Werner Herzog is certainly a filmmaker capable to stage and to direct landscapes (or maybe better: to invite landscapes to act for him, that vice versa, invite him to react to their ›physical‹ acting). But is not a friend’s library, with all its treasures, another magic place, as mythic as a jungle? And one might muse: Was it the friendship being decisive, the calls that his friend apparently had to make just when Werner Herzog dropped by? Visionary forces, a filmmakers’ creative forces are not underestimated here, but still the question remains: the library, the friend, the book – are these just words for: ›chance‹? Or did they, did it all, with Werner Herzog, work on Aguirre? Not to mention certain Tarzan movies, and not to mention at all the one book, the one chapter on Eldorado and, above all, the one page on Lope de Aguirre.

A still from Grizzly Man (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grizzly_Man) (picture: thevoid99.blogspot.ch)

The early 17th century painter and printmaker that Werner Herzog called the ›father of all modernity‹: Hercules Seghers (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hercules_Seghers), here with an Imaginary Landscape

And yes, why not, do read the Aguirre passage again, and under lamplight, like a real adventurer (picture: DS)

(Picture: DS)

(Picture: DS)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Lena and Werner Herzog (picture: zimbio.com)

© DS