M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY Visual Apprenticeship III  |

What does it mean to sum up visual education? Was there a kind of system in the end? A solid building that drew from all of his visual experiences that Giovanni Morelli had made in his life?

And we should like to answer this with respect to Morelli’s connoisseurial practices, and with quoting from the introduction to our Giovanni Morelli Study (Part II of this monograph):

»If Morelli did represent the 19th century of system-building and scientific progress, one might say that he is also representing the 19th century that had no patience to work systems out. And his heritage is not the least a difficult one, just because Morelli did not fully live up to his own ideals, and because he does at the same time represent a new culture and to some degree an old culture, that he meant to renew.«

VISUAL APPRENTICESHIP III:

(ONE) SUMMING UP VISUAL EDUCATION

OR: TEACHING OTHERS HOW TO SEE

(TWO) FOREIGN POLICY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP OR:

GIOVANNI MORELLI IN LONDON

(THREE) A NATIVITY, A FINAL WISH![]()

ONE) SUMMING UP VISUAL EDUCATION OR: TEACHING OTHERS HOW TO SEE

»In November 1531 intelligence was received at Rome that Fra Mariano Fetti buffoon to Leo the Xth but a fine connoisseur of art was dead and had left the office of the Piombo vacant.«

(Crowe/Cavalcaselle 1871, vol. 2, p. 350)

ATTRACTING PUPILS, REPRESENTING A SCHOOL

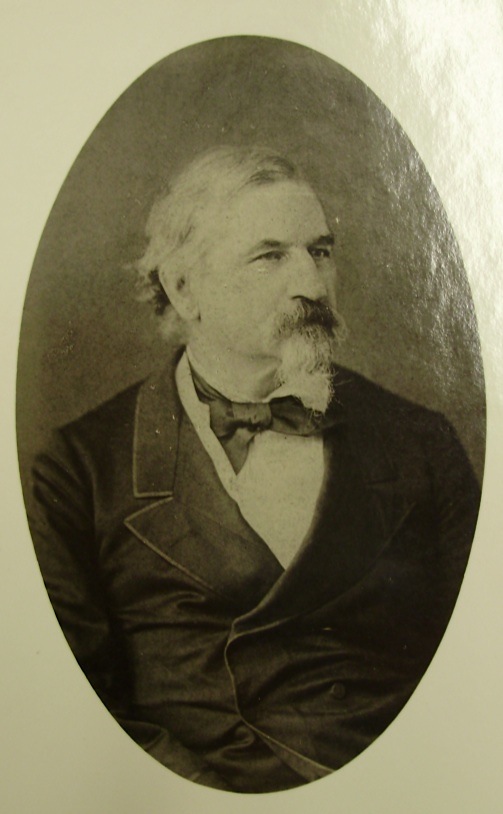

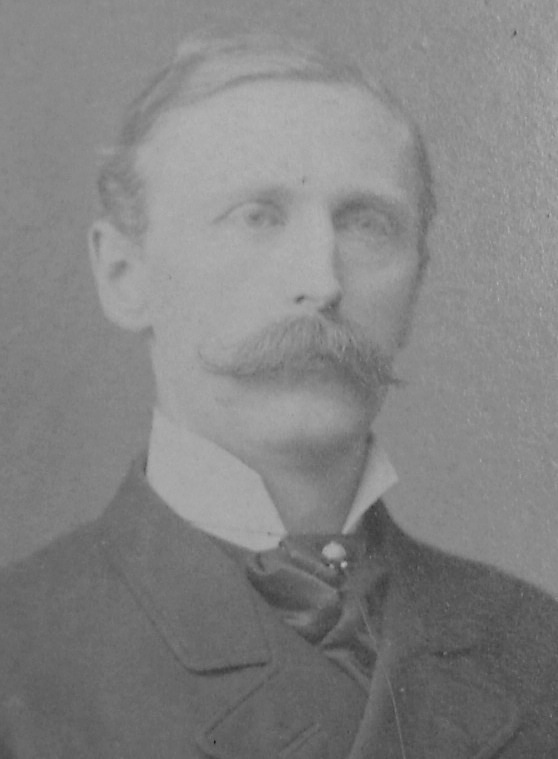

Based on a photograph, taken in or before 1878

by the Milanese photographer Giulio Rossi;

a card with this representation of him

Morelli gave away to friends with a dedication,

if asked for a picture

(picture: DS; after a photo print,

kept by the Bibliotheca Hertziana, Rome)

The decade of the 1880s saw Giovanni Morelli producing the great comedy that he, actually, did never write – the great comedy of connoisseurship.

Why is that? Haven’t we learned that he actually did write a comedy named Kunstkenner in his youth? And aren’t we well advised to think of the latest chapter of his life, as it were, as of the heroic age of connoisseurship, with Giovanni Morelli as the leading character, revolutionizing art history in implementing scientific connoisseurship?

The early play Kunstkenner does indeed count among Morelli’s juvenilia,(1) but above all: the present chapter is not meant to discuss the merits of Giovanni Morelli in that he did envision, and to some degree practiced scientific connoisseurship. Here we look more generally at his visual biography, that is: at the history of his ongoing visual apprenticeship (to the study of actual connoisseurial practices our Giovanni Morelli Study has been established). And the end of the decade of the 1870s shows him attracting pupils that were to become followers and even disciples, so that, during the 1880s, something could unfold, a something not lacking also seriousness, but something that, still, we do here interpret as the great comedy of connoisseurship.

With Morelli being the leading character, interpreting his role as the role of the king’s jester, but alternatively also as the role of the jester becoming king. With Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, his long-time antagonist, but also and alternatively with Wilhelm Bode being the whetstone of his wit. With the main plot of Giovanni Morelli now teaching others how to see, and with Giovanni Morelli – this the one principle of which, primarily, resulted comedy – with Morelli not telling everything to everyone.

No less than 60 changes of attribution Morelli had suggested to the gallery of Berlin, and at a time he still thought

that the gallery would consider his suggestions, Morelli held out the prospect to deal with the Berliners respectfully,

taking into consideration their sensitivities, in sum, performing an egg dance ›with agile hops‹ (GM to Jean Paul Richter,

26 February 1880).

Comedy resulted from Giovanni Morelli remaining an apprentice in looking. Because now it was about observing what others made, to the worse or to the better, of his approach, unfolding its (ambiguous) potential, including ideologies of how to look or not to look at things. Morelli, in a certain sense, multiplied in the uses that others made of him, and significantly, Morelli did observe himself being multiplied, but remained rather silent as to the conclusions that he drew. And certainly he had no better clue to what direction this all was turning than anyone. In a word: he was also curious to what end this comedy developed, with him as the one leading character, and with all the other characters.

And these others were friends and enemies, since his enemies’ opinions did matter seriously to him; and if an alleged enemy showed inclined to respect and even to praise Morelli’s merits, the roaring lion could easily turn into a tame house cat (which was, for example, the case with Anton Springer).(2)

On the other hand: one might also once attempt to question the all too familiar, the having become all too conventional view of regarding Wilhelm Bode as Morelli’s enemy. Replacing this view with the certainly heretical view of seeing in Bode a dedicated follower of Morelli. And even his most dedicated follower, since Bode remained openly critical and never showed inclined, as many a Morellian, to swallow everything Morelli said.(3)

With friends it was to become, occasionally, even more complicated than with enemies. Since Morelli did dislike having to speak frankly with friends and pupils, having to fully reveal what he – really and truthfully – thought of them.

This side of his character does not show in the single correspondence with a single friend, but with being able to read all his correspondences, and seeing Morelli act and maneuvering on various stages, keeping unpleasant news away from friends (that he preferred not to enlighten as to some errors), and not revealing potentially pleasant things to enemies, and also having to maneuver between various camps of friends (and enemies). And last but not least: with being able to observe Morelli observing.(4)

What unfolded was also a pedagogical experiment, raising the question if Morelli was actually a gifted teacher, but not only a pedagogical experiment. Also a serious campaign to put connoisseurship on a more firm footing, and with the most puzzling complications resulting from that campaign, of pupils and followers identifying with it (sometimes even more so than Morelli was inclined to identify with his own project).(5)

In a word: If one could see a church by daylight, one could see that it was about something serious, but that – notwithstanding – also comedy, not the least to Morelli’s own delight, resulted from all this.

Anton Springer (1825-1891),

to whom Morelli referred to, in 1882,

as his ›once adversary‹

(see GM to Jean Paul Richter, 18 July 1882),

while in 1881 he had intended

›digs in the ribs‹ for Springer

and ›kicks‹ for August Schmarsow

(see GM to Jean Paul Richter,

13 October 1881)

From the perspective of art historical tradition Giovanni Morelli had his appearance on the stage of art connoisseurship in 1874, when the first of a series of essays was being published in the Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst.

This means also than many of the people that had been dear to Morelli, that had been close to him, never got to know this final signature of his life. His friend Genelli never could see something else in Morelli than a poet that had given up his former scientific projects; Engelhardt had died in 1855; Capponi, at the end of his life, might have known something of Morelli’s plans to publish on Italian art. But Morelli, again, chose to published in another language than (maybe) expected. Now in German (again), because his articles were destined to a mainly German audience, and particularly destined to German professors that Morelli meant to attack and, to some degree, also to humiliate.(6)

Finally: his mother who had died in 1867, had known nothing of her son’s future career, his future fame, although she might have known about his plan to write a book on Italian galleries of art.(7)

The very thought, by the way, that the most important people had not known him, not known the person that he was now, was not alien to Morelli himself. And his obvious sensitiveness as to his own fortuna critica, his pretending not to care, if his views were accepted by the mainstream, while on the other hand he showed most touchy to any questioning of his authority (especially by young people), has to be seen against this backdrop, against this history of a very delayed career in print. In his own words:

›It’s not that I would concern myself with commendation or reproach of the world; since lonely and alone in this world as I am, I wouldn’t know either to whom to offer my fame? As only there would be one’s parents, for example, or a beloved person or the children, who would delight in that; and also I would remain unsensitive as to reproach, since nobody at all would care about that either.‹

····················································································································································································································

»Nicht etwa, dass es mir am Lobe oder am Tadel der Welt wohl gelegen wäre; denn einsam und allein in dieser Welt wie ich bin, wüsste ich auch nicht, wem ich meinen Ruhm bieten sollte? Sind es doch nur die Eltern etwa, oder eine geliebte Person oder die Kinder, die eine Freude darüber haben könnten; und ebenso liesse mich der Tadel unempfindlich, da um denselben ebenfalls sich kein Mensch bekümmern würde.«(8)

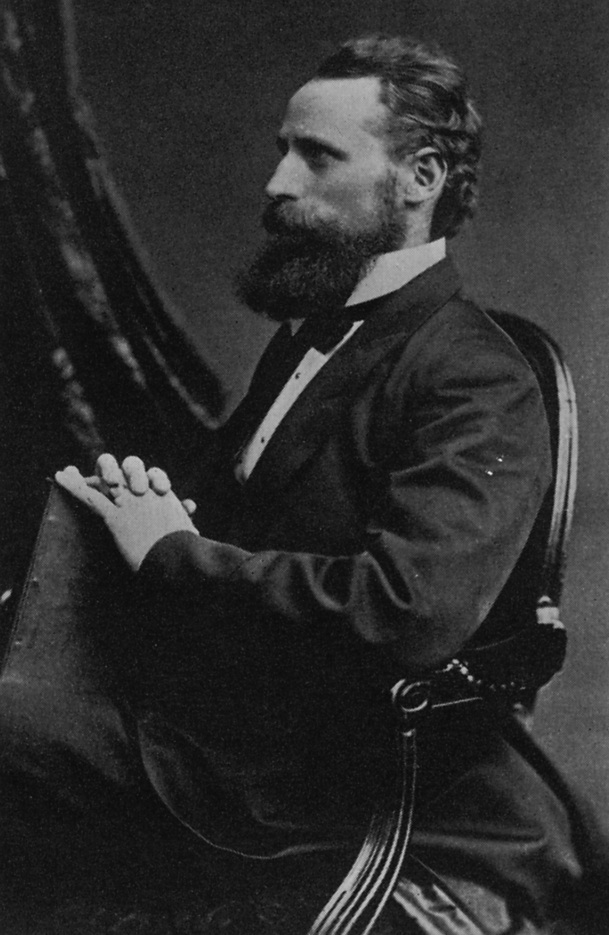

Jean Paul Richter (1847-1937)

(source: Bora (ed.) 1994, p. 91)

But the last decade of Morelli’s life does primarily show a Morelli invigorated, a Morelli vitalized. And this being invigorated was due mainly to one incident: somebody capable to invigorate Morelli with his interest and with his enthusiasm had come. Someone capable also to keep an enthusiasm, that had newly reignited in Morelli, alive, and someone even capable to foster that new enthusiasm: with being of support in any imaginable way. And, here, once more, one may again recall that Morelli had not had had a supportative cooperation partner like Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle had had and still had with Joseph Archer Crowe.

And this someone who had come now, in 1876, was Dresden-born Jean Paul Richter (1847-1937), who had turned – like once Otto Mündler had turned – from a study of theology to art historical studies. To – at first (and unlike Mündler) – Christian Archeology, and then to the study of Italian Renaissance art, of which, in 1876, when first meeting Morelli, Richter still knew rather little.(9)

But this, this knowing rather little, was, in hindsight, certainly to the better and not to the worse. Because this knowing rather little made Richter, an intelligent, if not overly sensitive scholar of indefatigable energy (comparable to Wilhelm Bode) – it helped him to become Morelli’s ideal student.

A model student Richter was to become, although it is also significant that Richter, today, is mainly recalled for having edited the Literary Writings of Leonardo da Vinci.

This had also much to do with Richter having met Morelli, but it had less to do with Richter delving in connoisseurship and becoming Morelli’s apprentice and model student. But both the achievements of Richter and of Morelli, especially those of the early 1880s, had much to do with them being capable of invigorating each other, to share a common fiery passion, a feu sacré for what they did (the studying of art) and the objects of that study (the works of art itself).

And this inner fire, as far as Morelli was concerned showed also graphically and visually. Since there were visible signs, vital expressions of newly vitalized enthusiasm, that show us that Morelli felt indeed invigorated and vitalized, if not to say rejuvenated (even if, at times, he felt like comparing himself, being age sixty, almost sixty-one, with Richter who – in the fall of 1876, when the two men first met – was 29 years old, thirty in January of 1877).(10)

The Giovanni Morelli Collection V: the »laboratory of a specialist«

(but also the head quarter of a ›school in polemics‹, that is: the Morellian school)

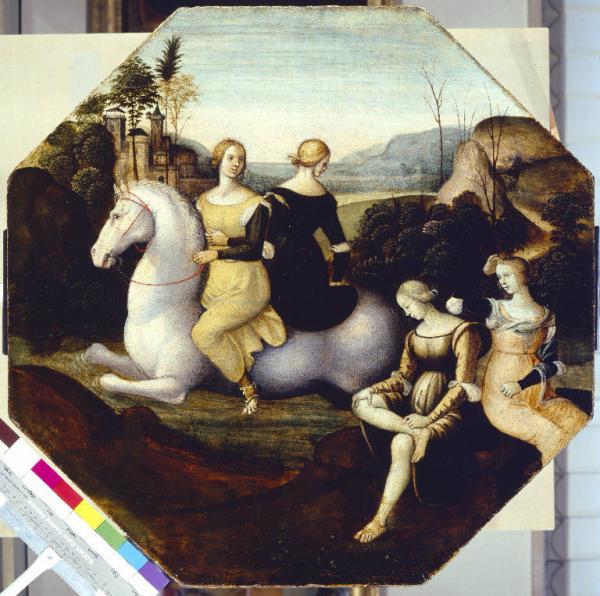

Martirio di San Bartolomeo by Bagnacavallo,

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

Morelli’s enthusiasm showed in being playfully enthusiastic and hilarious, in speaking of his child-like and also his childish fun he experienced.(11) It showed in Morelli using vivid language, and above all vivid metaphors.(12) Vital images speaking of vital things, but also and indirectly referring to his ideals of liveliness, vitality and verve. In life as well as in or displayed by works of art. And Morelli’s newly born enthusiasm showed not the least in Morelli wanting to attack, to polemicize, and this bears on one point in which Richter and Morelli not always did agree: to what extent being agressive and to attack publicly.(13) Since waggish playfulness was one thing, and Morelli did enjoy to imagine various degrees of being provocative: he did imagine to pester his enemies with digs in the rips, but he did also imagine giving them some kicks, kicking them himself or having them kicked, preferably, by some students of his, and also actual weaponry was, at times, being part of such fantasies.(14)

And as long, perhaps, as one did remember the pictures that were hanging on Morelli’s walls, one might have interpreted this also with a grain of salt, knowing that Morelli was only playing and much enjoying to play. But things were getting complicated as time went by. And not every ›enemy‹, not every scholar that Morelli perceived to be an enemy or that he pretended to be an enemy, felt that public attacks were only resulting from Morelli being playful. Not to speak of the images that certainly not everyone did know. And some attacks, indeed, did hurt.(15)

Nevertheless: the playful Morelli does show in his looking forward to welcome Richter – metaphorically speaking but also literally speaking – in his guestroom, and the liveliness and vividness of Morelli’s waggish expression draws here, particularly, of the vitality being inherent to the works of art that were the splendid ornament to that particular guest room, that was belonging to Morelli’s Milan flat in Via Pontaccio. And playfully, as we may imagine here, playfully this works of art might also have been arranged.

A VIRTUAL GUESTROOM

›I am awaiting you for the first days of the coming month here in 14, Via Pontaccio, and your companions in sleeping, the Ferrarese Grandi, Garofalo, Panetti as well as the Tuscans Pesellino, Matteo di Giovanni and Neroccio, in days to come are very impatient to make your personal acquaintance. I should hope that, under the custody of Madonnas and Saints, you are going to sleep gently and sweetly – which, as I do think, will be a reassurance to your spouse.‹

·····································

»Ich erwarte Sie für die ersten Tage des kommenden Monats hier in Via Pontaccio Nr. 14, und Ihre künftigen Schlafgefährten, sowohl die Ferraresen Grandi, Garofalo, Panetti als die Toskaner Pesellino, Matteo di Giovanni und Neroccio sind sehr ungeduldig, Ihre persönliche Bekanntschaft zu machen. Ich will hoffen, dass Sie da, unter der Obhut von Madonnen und Heiligen, sanft und süss schlafen werden – was, wie ich denke, Ihrer Frau Gemahlin zur Beruhigung gereichen dürfte.«

GM to Jean Paul Richter, 22 September 1880 (M/R, p. 128f.; all pictures: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

A later illustration to the novel À rebours by Huysmans,

wherein the antihero, Des Esseintes, does also consult a Baedeker of London

(Huysmans 1995, p. 157), for the passages on the London museums: texts that

Morelli’s pupil Jean Paul Richter, in 1879, had provided (see Seybold 2014a)

In 1884 writer Joris-Karl Huysmans published his novel À rebours with its notoriously decadent antihero Des Esseintes, destined to become an embodiment of European fin-de-siècle décadence.(16)

And this novel might serve us as an interesting backdrop to show that Giovanni Morelli could be seen as representing exactly the opposite of a decadent connoisseur of art, withdrawing from the world into his secret recluse, equipped with all the most chosen, the most rare and the most exclusive. And in fact Morelli, whose flat was also equipped with many an exclusive work of art, was exactly the opposite of someone like Des Esseintes, lacking the energy that one needed to actually live with people, and the energy that one also could draw on from living with people.

Since Giovanni Morelli, in these very years, felt not only invigorated, because Jean Paul Richter had come. But also because Morelli was given opportunity to attach to the whole Richter family (who in 1884 moved from England to Italy). And Morelli’s image, hence, multiplied within that family, in that it multiplied into the image that the children of Jean Paul and Louise M. Richter had of Herr Morelli (who dearly loved children),(17) the image that Louise M. Richter had (as of a dear friend, whom she, in any way, trusted as a friend and, not the least, also as the godfather of her eldest daughter Irma), and the image that Jean Paul Richter had of Giovanni Morelli, his well-respected teacher.

Morelli got attached to that one family, not because he was lacking opportunity to live with people. This was not the case at all, and the problem of Morelli, throughout his life, was rather that he was too popular to enjoy, from time to time, peace and quiet all by himself. He was much loved, and he also loved people in general. But with the Richter family it was special, since the Richter family was special. In that this particular family allowed him to combine being attached to a family with art historical studies that all the members of that family, in one or the other way, participated.

Since not only Jean Paul Richter was dedicated with reading and with listening to Morelli. To Louise M. Richter had been, already shortly after 1880, entrusted the task to provide Lermolieff, as Morelli put it, ›with an English overcoat‹ (she did provide the first translation of a book by Morelli into English, drawing also from first attempts to translate him, that had been carried out by Lady Eastlake).(18)

And Louise M. Richter was also proud that Morelli, occasionally, extended his teaching, gallantly, on her, if occasion was given, as for example in a public gallery.(19)

On the other hand Morelli also expanded his loud thinking on political issues. In that he entrusted many a view of Italian, of European political matters to Jean Paul Richter, whom, thus, Morelli did not only teach how to look at art, but also let him know, and often passionately, how he thought of politics.(20)

San Girolamo traduce la bibbia by Adam Elsheimer (school of),

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

If the Richter family was to become very familiar with Morelli as a man, one should not be mistaken that Morelli ever revealed everything to anyone. To Louise M. Richter, for example, it came as a surprise to be informed, after Morelli had died, that he had been of Protestant origins.(21) Since she had had perceived him as being Catholic, and one might draw one’s conclusion as to whether Morelli did somehow reveal his Protestant origins or his not being Catholic in his writings or not (for example in his speaking of saints as being the ›heroes of Christianity‹).(22)

In any way, Morelli was to become a tremendously admired and well-respected member of the Richter family, and his headquarter, if not being his own flat, was on many an occasion the Florence flat of the Richters, as long as this family stayed in Italy. They were some of the people closest to Morelli, but, as said, they also, in spite of being that close to Morelli, received as their dear guest someone who still kept essential things to himself only.

*

A MOLECULE AND ITS VARIOUS BONDS

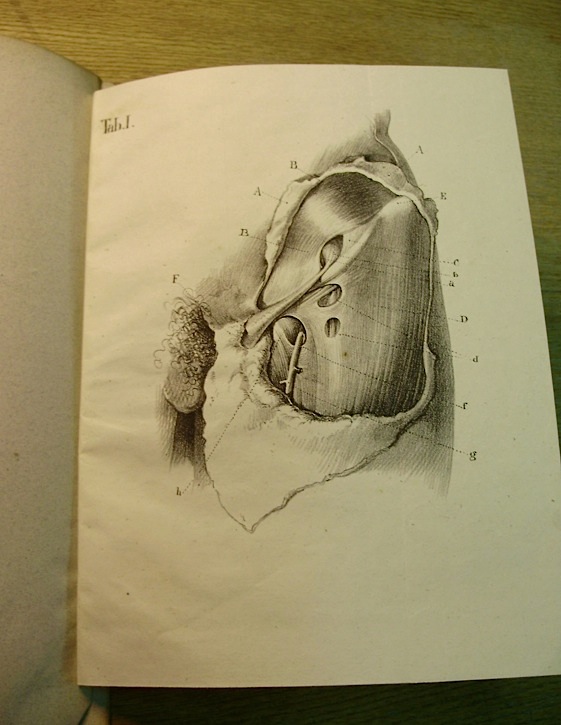

Table I from Morelli’s 1837 doctoral dissertation

on the groin (source: Morelli 1837; picture: DS)

›The last tersely review by Herr Prof. Dohme and his clique that you had most kindly informed me about is insofar unfair as regards me, as it never would have crossed my mind, nor could cross my mind of ›wanting to see the salvation of art history in the anatomically dissecting contemplation of painted canvas‹. I do very well understand that perhaps I am demanding too much, if I do claim that every art historian has to be, at the same time, also a connoisseur of art – as it is self-evident that, without anatomy, there is no such thing as a scientific physiology, nor could there be.‹

»Die letzte von Ihnen mir gütigst mitgeteilte kurzangebundene Rezension von Herrn Prof. Dohme und Konsorten ist insofern ungerecht gegen mich, als es mir doch nie eingefallen ist noch einfallen konnte, das Heil der Kunstgeschichte in der ›anatomisch sezierenden Betrachtung bemalter Leinwand sehen zu wollen‹. Ich begreife gar wohl, dass ich vielleicht zu viel verlange, wenn ich fordere, dass jeder Kunsthistoriker zugleich auch Kunstkenner sein müsse – so wie es sich von selbst versteht, dass es ohne Anatomie keine wissenschaftliche Physiologie gibt, noch geben kann.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 18 January 1881 (M/R, p. 144f.))

It might have come as a surprise to Jean Paul Richter, in 1878, that Morelli seemed to consider himself as somebody actually lacking an actual métier.(23)

Was Morelli indeed lacking a profession? Wasn’t he a senator? Hadn’t he been a polititian? Hadn’t he been a soldier, a freedom fighter, a doctor, a student of the natural sciences? And above all: Wasn’t he to be considered, at least now, as a connoisseur of art?

The answer that Richter might have given to himself we do not know: but Morelli indeed had practiced many activities. But had an actual profession been among those? What was a profession at all (and what was a connoisseur of art at all, since, for example, Richter also turned to become, to be one)?

Morelli was, much later, to speak of art historical, of connoisseurial studies as of the ›favourite working activity‹ of his life.(24) This might be regarded as telling: Since Morelli had indeed been searching for a long time, what exactly he wished to do in life. And many turns of his life do not explain mainly by his own decisions: one had wanted him to become a representative of Bergamo, a senator. He himself had referred, in early years, to the study of poetry (›Poesie‹) as being his favourite study (while studying actually comparative anatomy);(25) and his dream, like that of other first-ranking connoisseurs, had been to become a writer. To do actually something completely different than to practice applied connoisseurship and to envision scientific connoisseurship.

Now, in 1878, he had turned to be a connoisseur of art, and he was now also attracting pupils that chose to make him their leader. But the point we’re getting at here is that Morelli was still the same; still searching, still someone not exactly having found the one ideal role of his life. If there was such a role at all. If not his whole biography was to be seen rather in terms of a picaresque novel, which is: if there weren’t, for him, many roles, a diversity of roles (and this, having to fit into these diverse role, being his one role). And certainly Morelli would have liked to see his biography that way, himself as the leading character of a European picaresque novel, and swirling across the most diverse milieus and ambiances, being fit, thought as a single molecule, to throw inert materia, here and there, into a dither.

The cabinet that replaced, in 1876,

the government of Morelli’s friend Marco Minghetti

But Morelli himself, without any doubt, felt also the difficulty to unite his various interests and the various worlds he had been part of: the worlds of the natural sciences, the world of poetry, the world of politics and the world of art connoisseurship. Because these worlds did, for him, not simply unite, even if one was to fancy (like a late romantic) that everything that had been split and dissected would come together again, and that everything in the cosmos was connected with everything anyway.(26)

As charming as such a fantasy might seem – not to everyone did appeal the background of having studied comparative anatomy that, particularly, Giovanni Morelli did bring to art historical studies. Certainly, it was possible to find interesting intersections of these worlds (Marco Minghetti, for example, the statesman and Morelli’s friend, he represented the world of politics as, to some degree, he represented the study of Raphael as being Morelli’s pupil).(27)

But it is also possible to arrange, to picture these worlds Morelli had been part of as having little to do with each other as being very distinct systems of its own. And that dissecting of canvas was certainly not the future of art history at all. And deliberately we should like also to juxtapose images here that, at least, could be seen, could be interpreted as representing opposed directions of how to live, or of what to do in life, and also opposed views to look at life, and at works art.

Again: all-sided receptiveness seems to have been the one, the primal signature and if one likes: the key of and to Giovanni Morelli’s life, the signature that makes this biography memorable, and one might see and stress the rich diversity, the wealth of view points resulting from such a life (also to the benefit of a beholder); if one is not to miss the one real original idea, the one real original creation, or, perhaps, the more rigid endurance required by a student of the natural sciences or of a student of art (beyond the yet vital, but rather short-lived impulse).

And if one was not to miss, moreover, one thing: such as harmony. Because harmony is not what the picaresque novel is all about (being the genre more reflecting complicated identities and a general chaotic pluralism of life), and harmony was not what Giovanni Morelli’s biography seems to have been about. He complained, with a little mourning, about others misunderstanding him, declared that he had not suggested that art history was to turn into anatomy. And one can understand his complaint. On the other hand we do interpret exactly this mourning, this complaint as an expression of his being aware that it was difficult to explain to others who he had been, and who he actually was: because he was many persons, united in one, and still, and for most people, one Morelli.

What, on earth, might be a ›certain Raphaelesque something in the fingernails‹ or:

how does a Raphaelesque fingernail look like?

(compare Morelli 1890, pp. 45f. and 61: they do not stick out beyond the finger tips;

pictures below: Google Art Project for details from the Madonna del cardellino,

and Wikipedia for the Portrait of Maddalena Doni)

How was it with Raphael, for example? Was there just one Morelli, hight priest of a ›church of Raphael‹? Or was there the anatomist of art history, eager to dissect, and only eager – horribile dictu – to put fingernails under scrutiny, be it that these fingernails were fingernails rendered by divine Raphael? Someone who had become bored with may bugs, and had just transferred his being obsessed with detail to another area?

And might this have been his ›cult of the detail‹, notoriously having become famous?(28) And: How was someone to address Raphael, whose nature was all-sided receptiveness, including receptiveness in terms of human anatomy and physiology?

In fact Morelli had probably noticed as early as 1842 that the colliding of his various interests could produce nothing but comedy, or at least: also comedy (and, as he imagined, to the benefit of the Italian theatre). Comedy that also, throughout his life, was an expression of (his) serious interests colliding.

Knowing that Vasari had spoken of the ›certain something‹ in regard of Raphael; knowing also that Rumohr had adapted that thought, and having read Rumohr, and having found his inspiration for a waggishly taking a look at the characters of the great painters of the Renaissance, each imposing his will on all subjects – except Raphael, who was not monumental if he had to render delicate things (like Michelangelo was also monumental, if having to render the delicate), except Raphael who, for each subject had known to find the just, the adequate expression.(29)

This all has to be considered as the backdrop when Morelli, in 1861, was speaking, rather to himself, and probably not to Cavalcaselle with whom he was travelling, speaking, that is: writing of the ›certain something‹ – to be found in renderings of fingernails by Raphael.(30)

This was nothing but comedy, but without any doubt and at the same time: this was also very serious. Because this was about the basic order of things. Of art works. In history. And this resulted, if not in religious wars about Raphael throughout the 1880s, at least in small feuds at whose origins was Raphael (see our survey).

More precisely: identifications with Raphael. More precisely: colliding and irreconcilable perceptions of Raphael and his oeuvre, combined with and based on strong identifications with Raphael, and with the people having these identifications and perceptions of Raphael vying for definatory power as to how Raphael had to be seen.(31)

But neither for Morelli nor for his friend and, to some degree, pupil Marco Minghetti it was about thoughtless admiration or about a cult of the detail. On the contrary: their views of Raphael corresponded with their respective general look at life, had their root in their respective view of the world, and not in connoisseurial fancies of whatever kind, even if the meaning that could be given to detail (such as fingernails) occasionally might have fostered the view that it was only about cold dissecting and about hotheadded (and completely thoughtless) admiration.

Or about a cult of the detail.

Because for Marco Minghetti it was about the notion and the expression of a ›mild Catholicism‹ that found its expression in works of Raphael, whilst for Morelli it was, for example, about a rather secular Raphael, whose Madonna ›stepped out of the church‹ to become simply mother of a child,(32) and also about characters Raphael had rendered that appealed to Morelli, not only as characters but also as to the rendering, revealing and in-depth insight into human nature (which was the great ideal that throughout his life he found attained by the great writers, in Shakespeare as also in more contemporary writers like for example Manzoni, and also in the great artists as for example Raphael).

Nonetheless: to look at Raphael, to identify Raphael for certain, was also about detail, also about the now having become notoriously famous fingernails.

And in the more broad view and in hindsight it was about this detail because the quintessence was to be found in such detail. But not as to Raphael, as one may now think (contrary to what Morelli had been, at the same time waggishly and seriously, saying in 1861): but as to the various sides of Giovanni Morelli’s nature. Who knew himself that the colliding of his various interests was fit to produce comedy. And the strategy he chose was to have this comedy shine through his art historical writings, not attempting to purify these writings from anything that looked like comedy (which would have been against his own nature anyway). Or perhaps even purifying too much.

And probably there was also no other way than to allow his nature to express itself. In other words: the comedy, the comedic had to be accepted. To the danger that the various elements inherent to that comedy (the waggish element, the serious element) were now being dissected, looked at isolatedly, by other scholars, that were not being able to see, or not being able to accept, or not being willing to accept, that all this was the expression of one nature, whose signature had been and was all-sided receptiveness, and of one individual that had been studying also various disciplines of the natural sciences, including their classificatory systems, and classifications according to slight differences in minor detail. And had at least thought about a career in comparative anatomy.

›Without anatomy no physiology‹: in 1838 Morelli had also visited the Meckelsche Sammlung at Halle (see GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 14 June 1838; picture: hallespektrum.de)

According to Jean Paul Richter Morelli considered, in 1881, the Small Cowper Madonna as the most delightful of all Madonna pictures by Raphael

(see Jean Paul Richter to GM, 7 January 1881 (M/R, p. 142); both works were being exhibited in Paris in 1881; the above work Morelli does also name, in Morelli 1890, p. 46, as showing the Raphaelesque type of fingernails)

GIOVANNI MORELLI AND RAFFAELLO SANZIO

1837f.: in writing his second satirical piece, entitled Das Miasma diabolicum (Morelli 1839), Morelli is also concerned with Raphael and with the (Munich) political confessionalism’s perception of Raphael (compare Locatelli 2009, p. 50ff.); he also develops, while staying in a German cultural environment, a strong identification with Italian master painters and with Italian culture in general (compare Frizzoni 1893, pp. XXXIff.; GM to Federico Frizzoni, 21 February 1838).

1839: in Paris Morelli is reading Passavant’s monograph on Raphael (Frizzoni 1893, p. XXXV).

1842: in Rome, according to his own view, Morelli actually discovers Raphael; he thinks about penning down a play entitled Gli Artisti.

1861: during his trip with Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle to the Marche and to Umbria Morelli notices, when looking at a painting in Urbino, a ›certain Raphaelesque something in the fingernails‹ (Anderson 2000, p. 52).

1868 (c.): Morelli disapproves the Russian Grandduchess Maria Nicholayevna’s buying of a work by or attributed to Raphael.

1871: Morelli disapproves the selling of the Madonna Connestabile to the Tzar (see Morelli 1871; and see chapter Interlude II).

(Picture: artdaily.com)

1880: Lermolieff (in Morelli 1880, p. 248) does refer to the Sistine Madonna as being ›perhaps the most beautiful picture in the world‹ (this assertion, however, will not be repeated in Morelli 1891).

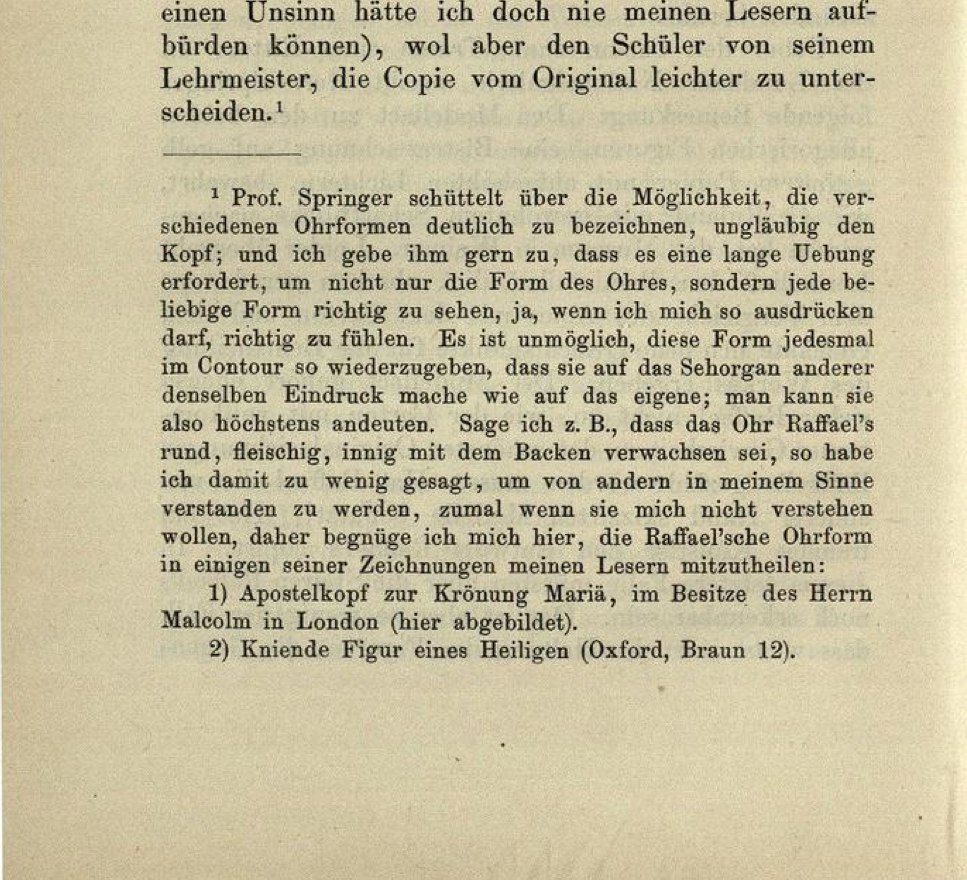

1882: in an article, directed against German art historian Anton Springer (Morelli 1882), Morelli muses about the Raphaelesque type of ear and the difficulties to represent it (in word or image) (see image above; taken from the reedition of the yet untranslated article in Morelli 1893 (p. 318)).

1883: the 400th birthday of Raphael is being celebrated (28 March), and around this jubilee Raphael literature is booming, which sets the backdrop to many a feud as to Raphael attributions throughout the 1880s; Morelli fights namely the opinions of Crowe/Cavalcaselle, Anton Springer, Friedrich Lippmann, Wilhelm Bode (see GM to Jean Paul Richter, 20 December 1882) and Eugène Müntz; his side also being represented by Marco Minghetti (who is less inclined to polemicizing, but relying on Lermolieff; see Minghetti 1885) and Jean Paul Richter (see especially Jean Paul Richter 1887); as regards Friedrich Lippmann Morelli had already in 1881 passed the remark that Raphael will ever be quite strange to the Jewish race (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 22 June 1881).

1886: an English banker named Hooker is eager to consult Morelli (who stays in Silvaplana in the Engadine) about a putative Raphael (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 16 August 1886 (M/R, p. 485)).

1889: Morelli has a conversation with the Austrian journalist Sigmund Münz about the Badrutt’s Palace Hotel’s alleged ›Raphael‹.

1890: Morelli does claim (in Morelli 1890, p. 99f., note 1; compare also Morelli 1893, p. 320, note 1, beginning on p. 318) that a Raphaelesque type of ear does show even in assorted portraits which he also does enlist (he does name, explicitly, the Palazzo Pitti Donna velata and Portrait of Pope Leo X [today: Uffizi], and the Portrait of Andrea Navagero and Agostino Beazzano in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj in Rome; see pictures on the left above, and on the right below); he has also the protagonists of his methodological causerie speak of the Raphaelesque type of ear (compare op. cit., p. 45f., p. 63).

(Visualization: DS; sources: Wikipedia and, in the middle, Morelli 1893, p. 319 (only detail being used here),

because of Morelli choosing this drawing to show his readers the Raphaelesque type of ear;

compare also p. 318, note 1; and see generally Cabinet V of our Giovanni Morelli Study)

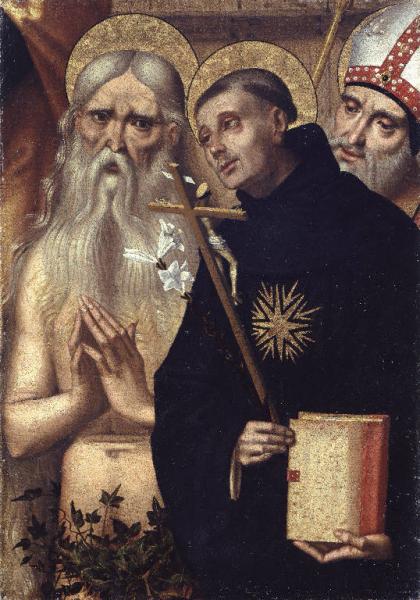

›Morelli: Perugino; today: copia da Raffaello eseguito da Berto di Giovanni‹

(compare: Agosti/Manca/Panzeri (eds.) 1993, vol. 2, pp. 331ff. (Silvia Ferino Pagden),

as well as vol. 3 with illustrations (No. 102); and compare also Locatelli 2011;

source of picture here: Lippmann 1881, p. 63)

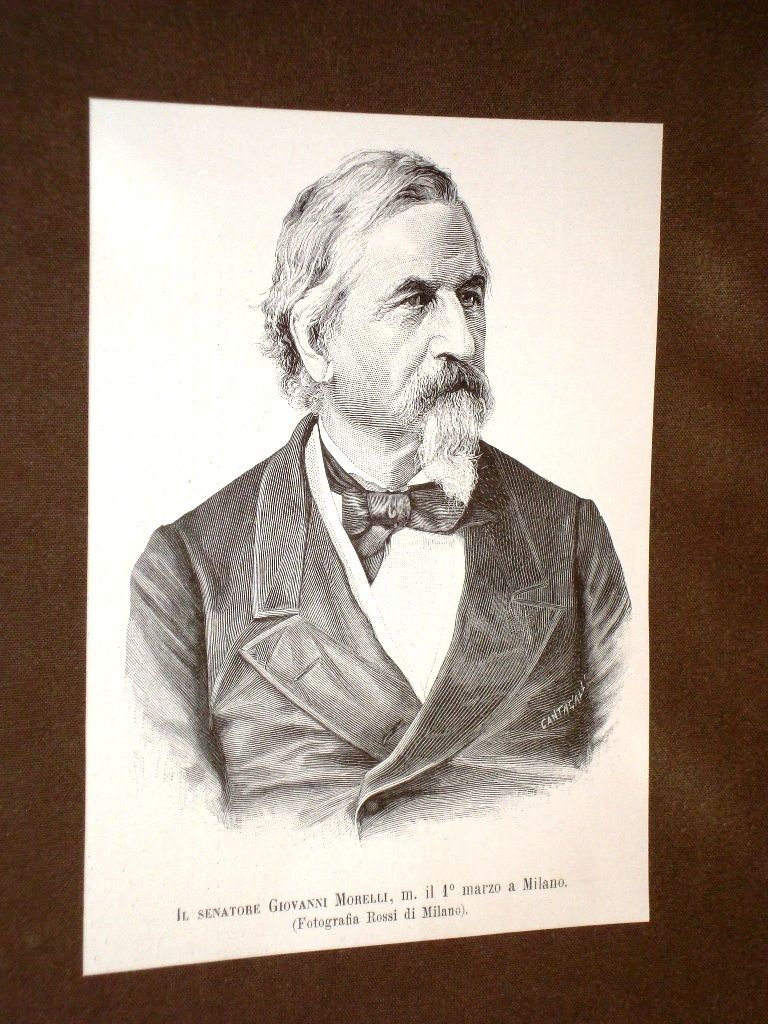

Marco Minghetti (1818-1886): whom Morelli had, at first,

harshly criticized, in 1864, due to the September Convention (Agosti 1985,

p. 67, note 22); but since the capital of Italy was to become Florence subsequently,

Morelli thanked him also happy years in Florence,

being the representative of Bergamo in parliament (compare Münz 1898, p. 103);

and he considered Marco Minghetti a splendid personality in the end,

although disagreeing with him for example as to whether one should support

trasformismo (with Morelli, naturally, being passionately against it

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 4 April 1887)).

**

TWO) FOREIGN POLICY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP OR: GIOVANNI MORELLI IN LONDON

THE EXPANSION OF THE NETWORK

In 1883 Morelli’s pupil Jean Paul Richter had dedicated his monumental two-volume edition of notes by Leonardo da Vinci to Queen Victoria.(33) Since Morelli had had more than a hand in the originating of this epoch-making work, a sort of bond between the connoisseur of art and the Queen, who had ascended to the throne in 1837, when Morelli had lived in Munich (and offered his friend Genelli as plaster cast of a lion’s bladebone), had already existed. And one may add that in 1839 both had enjoyed, in Paris, respectively in London, the show of lion-tamer Van Amburgh (that Edwin Landseer was to portrait amids his tamed, and already tame animals from inside the cage; with the picture to enter the Royal collections).(34)

But in the summer of 1887, the year of the fiftieth jubilee of the accession to the throne, Giovanni Morelli got actually presented to Queen Victoria.(35) To his great delight, as the eldest daughter of Queen Victoria, the Prussian Crown Princess Victoria, knew, but to a delight that Morelli, not uncharacteristically, seems to have kept more or less to himself. And to early (and modern) biographers, it seems, this meeting has remained completely unknown. Jean Paul Richter, however, knew about it, because he had accompanied his mentor to Windsor, but this time, it was not about his, not about Richter’s scholarly accomplishments (accomplished in tight cooperation with Morelli) – it was about Morelli, the hero of our picaresque novel that was his biography, to be presented to the Queen.(36)

As memorable as this encounter might have been (we do not know what exactly was happening), as memorable was also the aftermath. Since Victoria – eldest daughter of Queen Victoria and, since married to Friedrich Wilhelm, Crown Prince of Prussia, the Prussian Crown Princess – did write to her mother about Morelli subsequently:

»I also saw Morelli, who is still so delighted at having been presented to you and at having seen Windsor. He says you have some great treasures at Hampton Court which are but little known…«(37)

Someone knew, indeed, how one was to pull the strings.

And under different circumstances – what might have been the outcome? Another picaresque adventure of someone, in a former live perhaps a knight in Ariosto,(38) but now destined to become the Surveyor of the Royal picture collection? A role for which, by history and in the 20th century, another colorful individuality was casted, since history chose to cast this part with art historian Anthony Blunt, less a knight perhaps, but also an art historian, and not the least a 20th century style Soviet spy.

And if we allow here our imagination to be activated – also because of one, indeed most serious question: what does it mean to imagine, to envision things, if one is at the dusk of one’s life, if one does come near to the end of it?

Five years earlier, for example, Morelli had taken notice that his friend Moritz Thausing, at Vienna, had been keen to make him ›famous in Austria‹. ›It was a pity‹, Morelli had commented, that he, Morelli, was ›yet that old‹.(39)

What might he still have hoped for, in 1887? For himself, his pupils, and not the least for his project of putting connoisseurship on a more firm footing?

In any rate one might say that Morelli, with his having been presented to Queen Victoria, was on the peak of his career (if there was such thing as a career in a conventional sense). And his being able to get to this peak had much to do with his being able to charm and to make friends. And friendship, as we will see in the following, could have also strategic connotations, could be associated with future prospects, and this even if these friendships, as such, were warm and truthful.

(Source: Bora (ed.) 1994, p. 267)

Crown Princess Victoria in 1884

Rome-based writer Malwida von Meysenbug

was among those to portrait Morelli in print

(see Meysenbug 1898), stressing his more

serious, his ›aristocratic‹,

(and certainly not his waggish) side

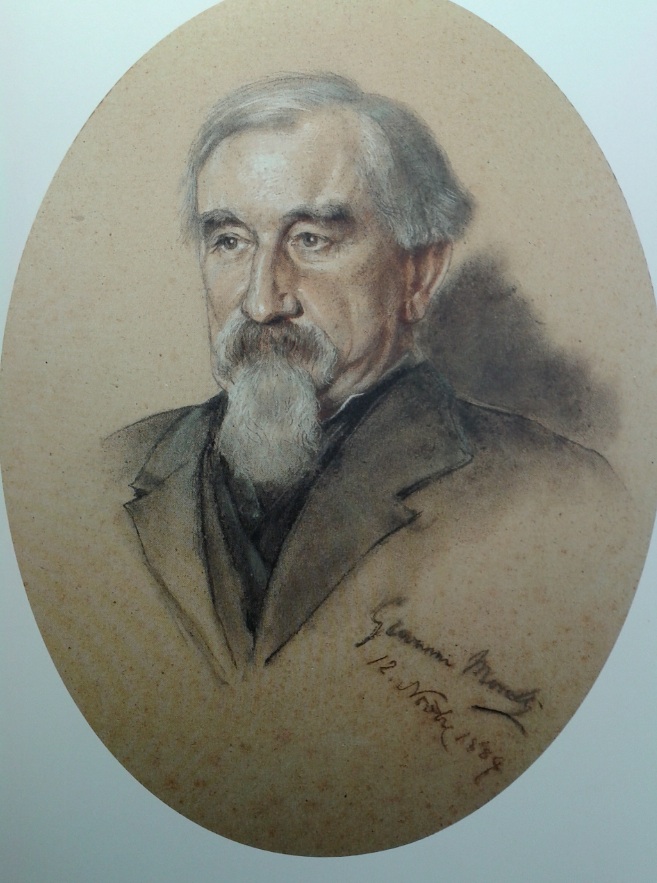

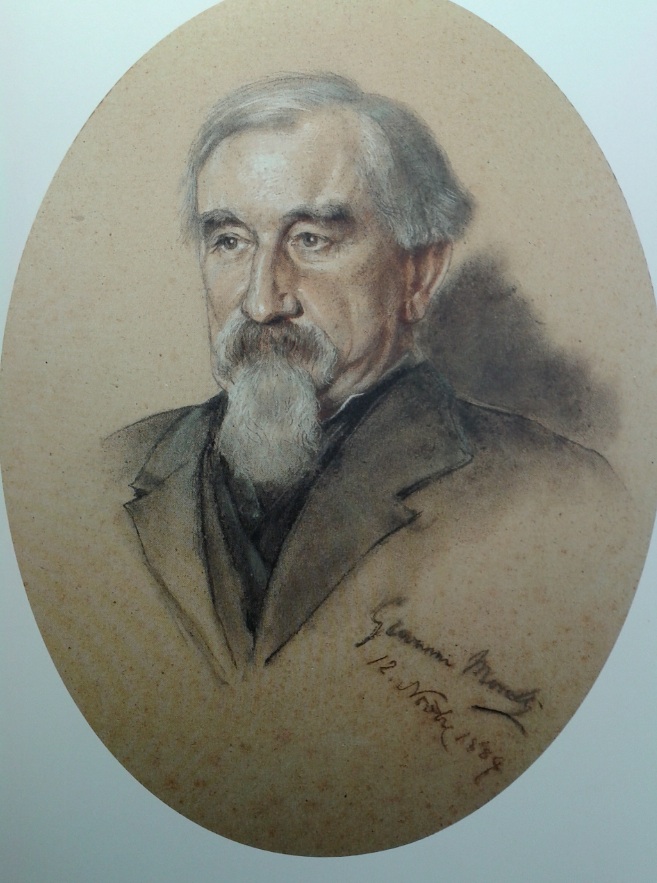

Various women have left us with very interesting views on Morelli,(40) but there is only one woman who in fact did provide us with an actual picture.(41) And this picture was considered, and is rightly so considered, as being simply the best, the most truthful visual rendering of Giovanni Morelli’s personality.(42)

And this woman, this gifted woman artist, all too little known as an artist, a woman better known for her rather tragic role in history (as the mother of Kaiser Wilhelm II), this remarkable woman who was able to represent or at least allude to the smiling eye of Morelli in portrait, was Victoria, Crown Princess of Prussia, eldest daughter of Queen Victoria. Who did create this memorable, but also all too little known portrait of Morelli in 1884.(43)

At that time she had known Morelli for about five years, and as truthful a friendship it was that had evolved, in 1879, between Victoria and her husband with Morelli – it is just this friendship that also shows that friendship, for Morelli, was or could be also about pulling the strings (compare our survey below). As far as this was possible, and as far as this remained compatible with the particular friendship. Because, here, it was about the friendship with the future rulers of Germany, and while Victoria could also be seen as the intellectually dominant part of the Prussian Royal couple,(44) Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm was also the protector of the Berlin museums.(45) In other words: he was the superior of Wilhelm Bode. And it is only all too obvious that Morelli was also keen to position his own man in reach of the Royal couple, prepared for, if circumstances would allow it, a moving into a position within the Berlin museum world. And this one man was of course, again, Jean Paul Richter.(46)

In 1887, when Morelli visited London again, he did also visit – with his entourage – Hampton Court

(see Jean Paul Richter, Diary, 28 July 1887; Louise M. Richter, Diary No. 4, 30 July)

(picture: Carom)

It is not about details here (that also can be found in the presentation below), but to show how Morelli’s network had expanded.

The network had been, in the 1860s, an Italian and English network, and one had cooperated in helping to manage the fatal prebrine crisis threatening Lombardic silk industries.

The network had also expanded to Austrian friends that had been tremendously important to push Morelli to an actually penning down of his connoisseurial views.

And with the arrival of Jean Paul Richter Morelli had found an able man, not only to manage several of his activities, but also to inform him about English and German affairs (especially after Lermolieff had been provided with the ›English overcoat‹ by Louise M. Richter), and to help him, possibly, to further spread Morellian views.

Not to speak of actually living the Morellian approach to connoisseurship, within an academical context or within the context of an important museum or collection.

Lermolieffianism was able, as Jean Paul Richter observed with Morelli, adapting also his style of speaking, ›conquered a province‹;(47) and this implied that Lermolieffianism was now unbound to conquer further.

It did not come to that. The age of Lermolieff the First, the age of Lermolieffianism was to remain rather short-lived. And this for various reasons. One being for example that, with Jean Paul Richter, not only the network had again been invigorated, but with Richter also tensions had been brought in or produced within the circle of Morelli. Tensions between Richter and Austen Henry Layard for example, due to Richter’s behaving more or less illoyal in business affairs, and Morelli maneuvered, attempting to manage these tensions, which, however, turned out to be not manageable.(48)

And other reasons added to a, as it were, strategic failure of Lermolieffianism (although Bernard Berenson was to come, but turned out to become – Berenson, BB, and not Lermolieff the Second), for example the fact that Richter, except becoming the advisor of industrialist and collector Ludwig Mond (who collected in close cooperation with the future benefactress of the Bibliotheca Hertziana, Henriette Hertz), never moved into an important position inside an art historical institution. And this not only due, but also due to one tragic incident: Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm was only to become the ruler, that is, emperor of Germany, for a very short time in 1888. Since shortly after his accession to the throne he died of cancer of the throat; and his son Wilhelm, subsequently, as Kaiser Wilhelm II, ascended to the throne. Leading also to the marginalizing of Victoria, his own mother (that tradition does also call Empress Frederick), since the relation of Wilhelm with his parents had been rather bad.

Morelli did observe all this (as our survey does also show), partly from very close, partly from a distance, while another new edition and also translation of his works were in preparation, with the Anglo-German network still working, but as one must also say, the relations between important members of that network having become rather tense.

*

THE ANGLO-GERMAN NETWORK

Lady Eastlake (1809-1893) (picture: flickr.com)

Sir Austen Henry Layard (1817-1894)

(picture: npg.org.uk; watercolor of 1891 by Ludwig Johann Passini)

Louise M. Richter (1850-1938) (with Sandro Richter) (picture: Gisela M. A. Richter 1972, p. 17)

GIOVANNI MORELLI AND CROWN PRINCESS VICTORIA (EMPRESS FREDERICK)

(Vanitas still life by Crown Princess Victoria: lombardiabeniculturali.it; landscape watercolor: kaiserinfriedrich.de;

pictures of Crown Princess Victoria and Crown Prince Frederick: Wikipedia (on top); kaiserinfriedrich.de; Bismarck: Wikipedia;

Fra Bartolomeo (National Gallery, London): bbc.co.uk)

1879: The Prussian Crown Princess Victoria and her husband, Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, who are in grief after having lost their son Waldemar, decide to spent the winter henceforth in Italy (see Sinclair 1983, pp. 263ff.; on the left in the middle a view of Pegli, painted by Victoria in 1879); Victoria, the first child of Queen Victoria, is also in grief after having lost, in 1878, her sister Alice; in November of 1879 they make the acquaintance of Giovanni Morelli who had been rather unpleased beforehand, thinking that he had to show the Royal Highnesses around as a ›Cicerone‹ (GM to Niccolò Antinori, 9 November 1879 (Agosti 1985, p. 74)); but the first meeting with the Princess and the Prince results with a big success, with Morelli hitting it off with Victoria and with Friedrich Wilhelm, and with Morelli showing them around at Bergamo, Cremona and Milan; after several days the tour of the royal couple is ended with a déjeuner à fourchette at Giovanni Morelli’s flat at Milan; he also presents a drawing by Cristoforo Alberti as a gift to the Princess (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 17 November 1879 (M/R, p. 91-93, with Morelli reporting on the tour on p. 92).

1879: »Über den Kunstsinn der deutschen Kronprinzessin hätte ich bisher sehr verschiedene Urteile gehört, und es ist mir sehr wichtig, was Sie über dieselbe mir mitteilen. Bode behauptet, sie sei obstinat und voller vorgefasster Meinungen. Es ist zu gütig von Ihnen, dass Sie meiner geringen Person im Gespräch mit derselben gedacht haben.«

(Jean Paul Richter to GM, 1 December 1879)

Translations

1880: In May Morelli spends 8 days with the Crown Princess, to show her Orvieto, Perugia, Assisi, Florence etc. (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 14 May 1880).

1881-1888: Battenberg affair.

1882: In August Morelli spends 6 days with Victoria and Friedrich Wilhelm at Baveno, where Victoria does also paint (see GM to Jean Paul Richter, 20 August 1882); the Crown Princess in the following presents Morelli with a painting done by her as a gift: the vanitas still life shown on the left, which became part of Morelli’s own collection and is now kept by the Accademia Carrara of Bergamo; Morelli, in a letter, refers to it as being ›utterly Spanish‹, resuming that the Crown Princess paints much better than a mere amateur‹ (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 10 November 1882).

»Ich habe also 6 für mich in der Beziehung höchst inhaltreiche Tage in der Mitte Ihrer k.k. Hoheiten in Baveno zugebracht – da wurde viel über Politik und über Kunst gesprochen, und ich bemerkte auch diesmal, dass der Kronprinz sich wirklich sehr für die Kunstsammlungen Berlins interessiert. Er sprach sich auch über das bekannte Rubensbild (Amphitrite) aus, indem er mir sagte, dass er nicht dafür war, dass man dies Bild ankaufen sollte – weder er noch die Kronprinzess, noch die Begleiter derselben, waren mit dem Bild zufrieden. Da mir das Bild selbst unbekannt ist, so konnte ich weder für noch gegen die Echtheit der Gemäldes etwas sagen – ich benutzte jedoch auch diese Gelegenheit, um sowohl Meyer als Bode mit warmen Worten zu preisen sowohl in Beziehung ihrer Kenntnisse als ihres Feuereifers für die ihnen anvertrauten Sammlungen und fügte hinzu, dass keine Galerie der Welt solche Leute an ihrer Spitze aufzuweisen hat – was sowohl der Kronprinz als die Kronprinzess mir auch gerne zugaben. Da diese letztere kein Wort über das Buch des Lermolieff je fallen liess, so habe ich mich wohlverständlich gehütet, ein derartiges Thema auf den Tisch zu bringen. […]. Auch diesmal haben beide, sowohl der Kronprinz als die Kronprinzess, einen sehr guten Eindruck auf mich gemacht – er als ein offener und sehr biederer Mann, sie durch ihre geistige Rührigkeit. Gewiss ist sie keine gewöhnliche Frau. Apropos – das Gespräch führte uns auch auf die Ankäufe Lippmanns, von dem der Kronprinz bemerkte, dass er ein wahres Génie sei im auffinden und im accappariren guter und seltener Kunstwerke, und da er mir in gewisser Beziehung ganz recht zu haben schien, so liess ich die Bemerkung vorbeigehen, ohne meinerseits etwas dazu zu sagen. Denn hätte der Kronprinz aber speziell die Ankäufe der Raffaelzeichnungen und des Dürerporträts (dessen ich mich wohl erinnere) gemeint, so würde ich gewiss einige Worte bescheidener Einsprüche dagegen haben fallen lassen.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 20 August 1882)

1883: in December Giovanni Morelli sees the Crown Prince twice in Rome, at festivities at the Capitol and, early in the morning and for several hours, at the Quirinale (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 23 December 1883).

1884: on November 12 Crown Princess Victoria portrays Giovanni Morelli, which results, according to Morelli’s pupil Jean Paul Richter, in the most adequate rendering of Giovanni Morelli’s personality (on the left on top; a detail view of which is also used here throughout; picture credit for both pictures is Bora (ed.) 1994, p. 267).

1885: in the fall Morelli’s pupil Jean Paul Richter consorts with the Crown Prince and the Crown Princess in Venice and once hears the Crown Princess giving a spirited characterization of Giovanni Morelli (Jean Paul Richter to GM, 11 October 1885).

»Und nun lassen Sie mich Ihnen meine grosse Freude mitteilen über Ihre persönliche Bekanntschaft mit der, wie Sie sie ganz richtig charakterisieren, »liebenswürdigen« Kronprinzess. Dies alles ist gerade so eingetroffen, wie ich mir’s nicht besser hätte wünschen können – selbst die Geschäfte mit dem Bildchen von B. Montagna. Sie werden mit der Zeit sehen, dass diese Ihre Begegnung mit der baldigen »Kaiserin« von Deutschland in Venedig Ihnen und Ihrer Familie von einigem Nutzen sein wird. Ich war dies Ihnen schuldig; da ich wohl einsehe, dass Ihre vielen läppischen Gegner, die Sie in Ihrem Vaterland haben, Ihnen hauptsächlich aus der Freundschaft, die Sie mit Lermolieff geschlossen haben, erwachsen sind.

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 28 September 1885)

»Statt gründlich für mich zu studieren, folge ich vielmehr jetzt der fast täglichen Aufforderung der Kronprinzess, mit ihr Kirchen zu besuchen, und wenn sie, wie es neuerdings überwiegend der Fall ist, zu Haus bleibt, um zu malen, so muss ich mit dem Kronprinzen ganz allein herumwandern, damit ich ihm Schönes zeige, ›das weder im Baedeker noch im Cicerone steht‹. Da er sich das nun gewöhnlich notiert, so schliesse ich daraus, dass er in Berlin im Scherz dann Bode seine Unterlassungssünden vorhalten will (während wir doch dem Kunstkorporal lieber ein ›si tacuisse‹ zurufen möchten). Wie oft hat mir die Kronprinzess gesagt, ich solle es Ihnen schreiben, wie entzückt sie von diesem oder jenem gewesen sei. So hat sie z.B. vor dem Altarbild des Paolo Veronese in der Kirche S. Caterina eine ganze halbe Stunde bewundernd zugebracht. Bei Tisch u bei Abendspaziergängen auf der Piazza hat sie sich merkwürdig vertrauensvoll über die Berliner Kunsthistoriker gegen mich ausgesprochen, wozu ich in der Regel nichts weiter gesagt habe, als dass ich die goldenen Zustände Englands dem entgegenhielt; denn (unter uns gesagt) dort haben die Kunsthistoriker die Kinderschuhe kaum erst angelegt. Verlorene Stunden habe ich hier auch darauf wieder verwendet (in Veranlassung der Kronprinz. Herrschaften) die Händlerbuden zu durchstreifen; ein recht lästiges Geschäft bei dem, wie zu erwarten, gar nichts herausgekommen ist.«

(Jean Paul Richter to GM, 7 October 1885)

1886: »Mit der Kronprinzess und dem Grafen Seckendorff, der Ihnen sehr zugetan ist, wurde oft und mit Liebe Ihrer und Ihrer werten Familie gedacht. Die Kronprinzess hat, wie es mir vorkam, besonders mein liebes Patenkind Irma [Richter] ins Auge gefasst. Der kleine Fra Bartolommeo [on the left above; it was later bought by Ludwig Mond; today: National Gallery, London] wurde mir von der Kronprinzess sehr gelobt – ich hatte gehofft, die hohen Herrschaften würden die seltene Gelegenheit, ein so feines Kleinod sich anzueignen, nicht unbenützt vorbeigehen lassen – allein bei Ihnen [probably: ihnen] scheint mir der Wille stets gut, allein der Geldbeutel stets schwach zu sein. Übrigens hat die hohe Frau, so wie auch Seckendorff, keinen rechten Sinn für die ›Goldne‹ Kunst [of the Renaissance] – ihrem Geschmack sagt mehr die ›Silberne‹ aus dem XVIIt Jahrhundert – und namentlich die ›Kupferne‹ aus der Zeit Louis XIV und XV zu. – Diesmal führte ich sie in den Dom [at Milan], wo der ›Schatz‹ mit seinen Silbergeräten und seinen Stickereien ihre ganze Aufmerksamkeit auf sich zogen. Dann besuchten wir auch unser Museo Civico mit seiner schönen Medaillensammlung, worunter der hohen Frau und auch dem Grafen Seckendorff besonders die Medaillen aus dem Ende des XVI. und aus dem Anfange des XVII. Jahrhundert gefielen. Es versteht sich von selbst, dass auch einige Trödlerbuden besucht werden mussten – allein, wie gewöhnlich, ohne Resultat. – Für mich ist es eine wahre Pein, mich zwischen den sog. Kunstwerken, die man in solchen Judenboutiquen vorfindet [sic; for Morelli’s views of Jews see chapter Visual Apprenticeship I], herumzubewegen – das Zeug ekelt mich an. Und doch hab’ ich auch in den 3 Tagen, die ich neulich bei Layard’s in Venedig zubrachte, mehrere solcher Buden mit Sir Henry besuchen müssen – doch ohne etwas wünschenswertes darin zu finden, eine herrliche Marmorbüste eines Grimani des [der] Vittoria ausgenommen. Mercato verlangte aber 20,000 Pfund dafür – und dies war Sir Henry doch zu gesalzen.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 14 November 1886)

(Picture: Uwe Thobae; Alessandro Vittoria, Bust of Ottavio Grimani, Berlin)

1887: In March medical treatment of the Crown Prince’s throat begins (he is diagnosed with cancer of the throat only in November; see Pakula 1995, p. 449).

»Maler [Ascan] Lutteroth aus Hamburg, der mit dem deutschen Kronprinzen sehr befreundet ist, besuchte mich gestern mit seiner Gemahlin – auch er versicherte mich, dass an der gefährlichen Halskrankheit des trefflichen Kronprinzen kein wahres Wort ist, was auch ich dem letzten an mich gerichteten Brief des Grafen Seckendorff entnehmen konnte. In meinen Augen wäre es ein wahres Unglück für Europa, wenn, statt des jetzigen Kronprinzen, sein Sohn Wilhelm auf den deutschen Thron kommen sollte!«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 26 May 1887);

in July Morelli visits England; on July 9 he sees Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm at Buckingham Palace (Baumgart (ed.) 2012, p. 542); he is also presented, at Windsor, to Queen Victoria (see diary of Jean Paul Richter, 11 July 1887; and compare Ramm (ed.) 1990, p. 58); in the fall he stays with the Crown Prince at Baveno, trying to entertain him (Münz 1898, p. 100).

»Sind die Zeitungsberichte wahr, so hat sich in diesen letzten paar Wochen der Gesundheitszustand unsers verehrten dt. Kronprinzen merklich gebessert, was mich, wie Sie sich wohl denken können, unendlich freuen würde; ganz und gar wage ich es doch nicht, mich dieser Freude zu überlassen – da ich in diesem Falle annehmen möchte, dass alle jene hohen medizinischen Autoritäten falsch gesehen hätten.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 23 December 1887)

1888: »[…] auch sagen die öffentl. Blätter, dass nach Ankunft Doctor Bergmanns in S. Remo es dort zwischen ihm und unserer lieben Kronprinzess zu herben Diskussionen gekommen sein soll, in Folge derer der engl. Arzt Mackenzie verabschiedet wurde u.s.f. – Ich kann mir lebhaft den Gemütszustand der hohen Frau vorstellen; sie muss sowohl in ihrem Herzen als in ihrem Stolz tief gekränkt sein. Sollte nun dies alles zum besten der Gesundheit unsers hochverehrten Kronprinzen statt gehabt haben, so sollen wir alle Gott danken, dass es so gekommen ist; ich fürchte jedoch dass man dabei schwerlich etwas gewinnen wird – – welch tragisches Geschick!!«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 1 March, 1888)

1888: The Year of Three Emperors: After the death of the German Kaiser the former Crown Prince accedes to the throne as Frederick III., but dies of cancer soon afterwards; Wilhelm, the eldest son of Victoria and Frederick, whose relation with his parents is bad, accedes to the throne as Wilhelm II.

»Den massvollen, freundlichen, in jeder Beziehung herrlichen Mann werde ich nie aus dem Herzen verlieren und stets mit inniger Freude der Stunden gedenken, in denen ich das Glück gehabt, in vertrauten Gesprächen mit dem hohen Herrn zu verkehren, und meine Gedanken mit den seinigen auszutauschen. Dies Gedächtnis an ihn wird, so lange ich noch lebe, mir heilig sein. Ich kann nicht an ihn zurückdenken, ohne in der männlich schönen und edlen Erscheinung vor allem in ihm den anspruchslosen Helden zu bewundern – er war für mich stets das Ideal eines deutschen Mannes! Und unsere treffliche Kaiserin Victoria – welch’ trostlose Zukunft würde ihrer warten, wenn sie eine Frau gewöhnlichen Schlages wäre! Allein die reiche Quelle von Energie und Lust zu schaffen, die in ihrer Brust liegt, wird sie retten. Trotzdem muss sie sich, zumal in dieser ersten Zeit, auf trübe, peinliche Stunden gefasst machen, denn sie hat der Feinde gar viele in Deutschland, zumal in den höhern Kreisen und unter den Seinen.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 28 June 1888)

1889: »Unsere hohe Gönnerin, die Kaiserin Victoria, sieht trotz ihren vielen Leiden doch gut und gesund aus. Ihre beiderseitigen Grüsse, die ich schon am ersten Abend [in Venice] Gelegenheit hatte, der hohen Frau darzubringen, wurden von ihr sehr liebreich angenommen, und sie erkundigte sich sofort nach Ihrem Wohlergehen und dem Ihrer Familie. Leider musste ich den ganzen Montag mit ihr und Layards von einem Kunstjuden [sic; for Morelli’s views of Jews see chapter Visual Apprenticeship I] zum andern ziehen. Sie kaufte ein marmornes Tor (vom Jahre 1495) und einen sehr guten ›Kamin‹ (aus Stein) ebenfalls aus dem Ende des XV. Jahrhunderts. Sie wird etwa 3 Monate des nächsten Winters teils in Neapel, teils in Rom und Florenz zubringen. Den Dienstag früh 7 Uhr dampfte das L[l]oyddampfschiff mit der griechischen Braut nach Korinth ab.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 24 October 1889)

Translations

*

STRETCHING THE NETWORK, FINALLY DECAY

Ritratto feminile by Cavazzola,

from Morelli’s own collection

(picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

For the tripartite drama

of Giovanni Morelli attempting to visualize his thoughs

see Cabinet II of our Giovanni Morelli Study

(namely question/answer No. 16)

Although new editions of works by Morelli were forthcoming, one might choose to describe the final years as years of cooperation within a network or: as a network being in decay.

Jean Paul Richter, who had been introduced, in 1879, to Morelli’s English friends, resulting with Richter being able to establish in London circles as a scholar and as a Morellian connoisseur (and as a marchand amateur, living on applied connoisseurship), had managed to make himself very unpopular in English circles (not the least because he had trumpeted out some of Morelli’s views, that Morelli rather preferred not to let his English friends know).(49)

Louise M. Richter translation of Morelli’s book of 1880 was considered by Morelli’s English friends as being rather bad (the first three pages, by the way, had been translated by Lady Eastlake, who was now also among those disliking Jean Paul Richter, after she had supported the Richters in early days).(50)

Morelli, on his part, seemed less to care about the quality of the translation, and still would have preferred that a new translation was made, again, in the house of the Richters (since Jean Paul Richter was supposed to supervise the translation).(51)

But in the end, and also since Louise M. Richter, being pregnant, stepped back from the task,(52) this new translation was entrusted to Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes, a young art student from Wales, who was taken under the wing of Jean Paul Richter and Morelli.(53) Resulting with the jealousy of Louise M. Richter, not because of the translation, but because she felt less supported by her own husband, who liked to mentor and to support Ffoulkes.(54)

Last but not least: the relation between Morelli and Richter developed to be rather complicated, because Richter felt, at times, patronized, and it is strikingly significant that he chose to do something, that, at Morelli’s lifetime, and being eager to avoid open rupture, he would probably never have done: after Morelli had died, in 1891, Richter sold a work by Giorgione, the Portrait of a young Man (see picture below), that, in cooperation with Morelli, he had actually yet recently attributed to Giorgione, to the gallery of Berlin, to Wilhelm Bode. Only after the death of Morelli, thus, Richter crossed the line, a red line, as to securing important works of great artists (like The Tempest, see also below), if possible, for Italian museums and collections, and a red line as to cooperating with Bode, and in a way, and at least as to this one case, in that he became his agent – changing side.(55)

(Picture of Wilhelm Bode: photo by author after a carte de visite in the Nachlass Jean Paul Richter, kept by the Bibliotheca Hertziana, Rome)

Scena popolare by Job Berckheyde,

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

All in all one might say that human comedy did not prevent Morelli’s books from appearing in print in the end. But on the other hand one should also stay aware that one volume of Morelli’s critical studies (Morelli 1893) remained untranslated.

And since this volume does also contain his three essays on Raphael (Morelli 1881; 1882; 1887) that only had appeared in German, also these essays were never published in English or Italian.

Even more important, and still little known might also be the fact that the little Morelli actually, but timidly, did to dispel misunderstanding as to his method, he did insert a) into one of these essays on Raphael, and b) into the second volume of his critical studies.(56) Resulting with the crucial passage from Morelli 1891 at least being spread among English readers. But Italian readers, if not being able to read German or English, were, until recently,(57) not confronted at all with Morelli trying to dispel misunderstanding (for this and other matters as regards Morelli’s working practices and particularly the Morellian method see Cabinet II of our Giovanni Morelli Study).

**

THREE) A NATIVITY, A FINAL WISH

A Nativity by Lorenzo di Credi (school of),

from Morelli’s own collection

(picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)