M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM From Bruegel to Solarpunk   Iconography of Sustainability 3 |

See also series 1 and series 2

(7.9.2022) ›What a magnificent logo!‹, my honorable reader may think. Did Dietrich do this himself? Yes and no. I had the artificial intelligence named Craiyon (it is the yet generally available mini version of Dall-E 2) visualize the notion of sustainability. I will come back to that mini adventure later, but this logo is indeed quite acceptable. It is obviously inspired by the circular-economy-, respectively the recycling-symbol. Crayon seems to have reworked it in gouache. It only did take about half a minute. The brushwork is okay. Well done, Crayon; we will discuss some of your recent works (prompted by me) at a later date.

With this third series of Iconography of Sustainability, we can build upon some earlier discussions. We have seen that one may take artist Pieter Bruegel as a starting point (as well as some much earlier artists); and thus we can discuss a whole art history of sustainability. This historical perspective is useful and important, since in our days we actually encounter one particular iconography of sustainability, which is the so-called Solarpunk movement, if it can be called a movement. At least it seems to be a trend, a zeitgeisty trend, or at least a slogan, around which optimistic visions of the future, a sustainable future, do gather. We will discuss also this trend at a later date and in more detail. But I have chosen my title for this third series with the thought in mind that Solarpunk at least is an attempt to visualize and to make more graspable what sustainability does look like, while much of the imagery of sustainability certainly is rather vain and also very hypocritical. This has to do, perhaps, with the fact that the discourse of sustainability, in its nature, is non-commital, since the proof for something, our economy, for example, to be built on the principles of sustainability can only be found in the future. It does cost us nothing to say that something is ›good for the climate‹ (while actually it may be only ›less bad‹ than something else), and only the next generations will know if there had been at least some truth in our declaration.

Much of the discourse on sustainability may be vain, empty and hypocritical, since we see the height of popularity as to this concept now, while, at the same time, we are realizing that much of political strategies and concepts of recent years have already proven to be completely unsustainable (policy of debts; dependency on gas and oil from dubious sources; waiver of atomic energy perhaps; and also the changeover towards sustainable energy and resource management in general). Is the concept, the slogan of sustainability more than a mere compensation, an illusion, an empty promise? Certainly, it is. But to realize this, one must dig deeper. And also into the more recent history of sustainability. We therefore conclude this introduction with some dates: after the year of 2000: the discourse of degrowth is becoming more prominent; mid-2000s: the corporate world is embracing the concept of sustainability; 2022: (in my view) heigth of popularity of the concept of sustainability in the ad-industry, disguising the question, if the consumption of what is advertized, indeed contributes to sustainability (or is only ›less bad‹, ›less ethically wrong‹ than the consumption of something else).

(Picture: thenextlevel.ch)

(Picture: DS)

Animals:

(14.11.2022) The iconography of sustainability is also populated by many animals. See panda, hedgehog and ladybird on the left (ecopower fuelstation); and note the more artificial bird on the right (recycling bin). These bins are usually also populated by (real) insects, living on the leftovers of humans’ drinks (not rarely based on sugar).

Craiyon:

(14.11.2022) When I prompted the artificial intelligence Craiyon to visualize the notion of sustainability, it came also up, among other things, with these two suggestions:

Also nice work, but also a little subversive, I must say, since, while the logo I am using here, clearly can symbolize ›circular economy‹, the economies represented by these two other suggestions do not seem to comply to the ideals of sustainability. These economies do rather seem to function according to the principle of ›externalizing the costs‹ or ›living at the expense of others, enduring the effects of growth‹ (with the symbol of circular economy being somewhat deconstructed and circularity actually being broken). But perhaps Craiyon does simply describe the state of things: the ecobabble of economies, not functioning according to the principle of sustainability, but suggesting all the times they are, or at least that they are working towards that goal. If this is it, Craiyon, I must say, seems also to be capable of producing productive misunderstandings.

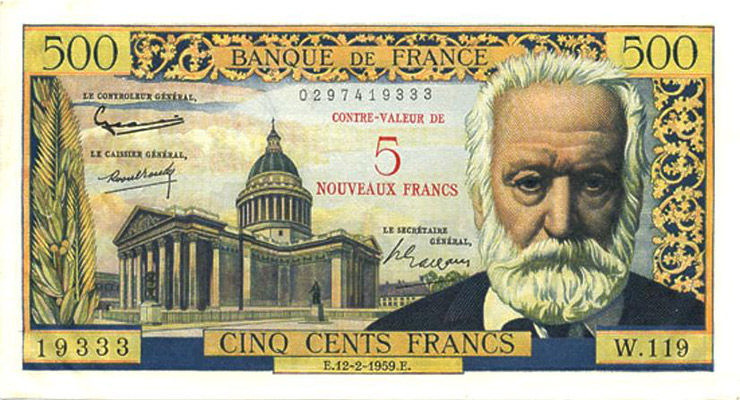

(Picture: coinsworld.eu)

Emergency Supply:

(14.11.2022) After Pablo Picasso had died in 1973, apparently a suitcase filled with 500-francs notes was found under his bed (see Fox I, 30 and 163). It seems that it was spectacularly rich Picasso who might have provided for dire conditions perhaps to come. – Or it was just playful superrich Picasso, who arranged this emergency supply, producing the effect of a gangster preparing to get away with his ›getwaway money‹. And I would prefer this explanation, since the hiding place – under his bed – does look a little bit like saying: find me. But perhaps it was just for one, or for many, of the many projects Picasso used to support rather informally.

Foresight:

(14.11.2022) Recently I’ve come across an ad which was saying: ›also we (our company) does pollute the environement, but we are not doing ›greenwashing‹‹. And this message, I think, is rather remarkable. The marketing people seem to have become aware of a new trend: which is not ›sustainability‹ or ›sustainable investment‹, but rather a growing critique of greenwashing, and of marketing people just suggesting sustainability of stocks and funds. Here we are encountering real foresight, as one may say, since this ad is already countering this critique (while most other ads just still seem to celebrate sustainability in a big collective frenzy of sustainability, a frenzy of wise foresight – while, in truth, the Swiss governement found it too much to be demanded from people, that they should care about possible shortcomings of gaz and power already in the summer, while it was hot, and not only in the fall).

Foresight has to be complimented with hindsight, and I am recommending an interview with a pioneer of sustainable investment, Reto Ringger, as to the history of sustainable investment and the current state of confusion, as to actual compliance of such financial products to the principle of sustainability (›the compliance guys have taken over from the marketing guys‹), published in themarket/NZZ, 23.9.2022, p. 17f.

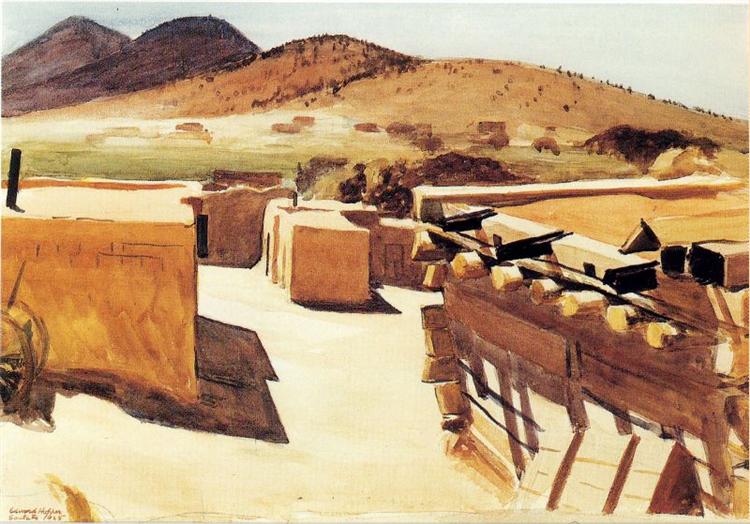

(Picture: wikiart.org)

Hopper and Sustainability:

(Picture: dsdugan)

(27.9.2022) Hopper biographer Gail Levin notes that in 1925, when American painter Edward Hopper visited the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico, street lights were still lacking in that city. Hopper, apparently, did not much like the place, but provided us with a number of watercolors, some of which did not reflect, as the – modern – expectation to see street lights, progress, but rather, as it seems, the ever attractive possibility to build houses out of mudbrick. Thus Hopper, without knowing it, associated himself with the discourse of sustainability, because, today, such Adobe houses, are being discussed in the context of Sustainable architecture – and thus sustainability (see for example here). The Spaniards had named them, but the Native-Americans had built them (as other civilizations had, in other places around the world).

Labels:

(14.11.2022) Eco-labels do seem to exist since the early 1990s. The growing popularity of products, labelled as ecologically produced, has resulted now with a diversity not easy to overlook. A word has been created for that confusion: ›Labelsalat‹ or ›label salad‹.

Picasso and Sustainability:

(31.8.2022) There once was a time when the subject of bullfight was a most prominent subject in the visual arts. These times may have passed, although recently Ena Swansea has brought the subject back, and although, of course, the metaphor of bullfight might be referred to as being a part of the global imagination: it was chairman Mao who once described his relation with Nikita Khrushchev as a ›bullfight‹ (with Mao himself as the bullfighter and Khrushchev as the bull (see Cambridge History of Russia, vol. 3, p. 384; contribution of William Taubman). This was probably referring to the Sino-Soviet split after 1956.

Of course it had been Pablo Picasso (working in the tradition of Goya) thanks to whom the subject of bullfight had gained such prominence in the arts of the 20th century. Picasso might have been the lens, but people from his orbit – such as the photographer Lucien Clergue who did produce very impressive bullfight imagery – contributed to the popularity of the subject as well (and one could also name writers such as Michel Leiris and Jean Cocteau).

The tides may have turned. I am writing about the imagery of sustainability, about the art history of sustainability, and this at a time the popularity of this concept is probably at its all-time height – and I am returning to Picasso, and I am returning to the subject of bullfight. Why is that?

I am returning to Picasso for a number of reasons. He does not seem to be the artist one would associate with the concept of sustainability, but on the other hand, if he would live today, given his vast production of occasional graphic design, one might imagine that he would have contributed sheets not only for the peace movement, but also for ecological purposes. Brief: Picasso is an interesting test case. Is the concept of sustainability completely absent from his art and thinking? And of course it is not. But one has to look carefully to find traces of it.

Sustainability in its popularized sense, today, is nothing but a promise (perhaps a bet) that something will go on and might go on forever, since the future of that something is well-secured. Which means that sustainaibility-thinking, on some level, can also turn into or be named to be a kind of religious thinking. It says that, beyond individual death, there is a future (for the next generations). But it has to be secured and it can be secured (not everyone agrees to that today; and the truth of that promise can only be tested in the future – by the next generation, and it is probably exactly this non-committal promise that makes the concept so popular today).

Picasso, as it is well known, was obsessed with death, and to study his bullfight imagery is one way to study this obsession. Rather accidentally I have stumbled over one particular sheet from his 1957 bullfight series: a rather magnificent depiction of bulls, not in an arena, but out at feed (for copyright reasons I am not showing works of Picasso here, but it is easy to find).

I know that one classic argument for the bullfight is that those bulls brought up to fight, the fighting bulls, have a good life before, appropriate for the species as one would say today. In a jargon that would be rather unfamiliar to Picasso, but in his obsession to cover the subject of bullfight in an almost encyclopedic way, which was probably also a search for his own childhood, since his father had brought him to the arena and had attended bullfights with him – in his search Picasso also had turned to the breed of fighting bulls, to the economy, as one might say as well, on which the bullfight is based, and which has to be organized according to the traditional principles of sustainability. To secure the future of the bullfight.

While I am recalling that, during an argument at school, I even have heard the argument of the good life of the bulls myself once, I am also musing about Picasso attending bullfights with his two sons, Paulo and Claude. We have good knowledge that he did so. Especially with Claude he attended bullfights in a father-with-his son manner in the south of France, discussed with him what had happened in the arena, so that Claude Picasso could relate such scenes later, and one could say that Picasso had cared for a pattern to repeat, a tradition to transmit, within his (rather complicated) patchwork-family.

It is true that Picasso is certainly not an artist whose oeuvre would be centered in an abstract concept such as sustainability. But the essence of sustainability is so fundamental that, on the other hand, one could easily imagine Picasso, instead of ›fighting‹ with the Meninas by Velázquez (also 1957), paraphrasing the Water-seller of Seville by Velázquez, which is so obviously about the inter-generational relation, about the transmitting of something from old to young (so that the future of a tradition can be secured).

Picasso may have been an artist whose work was centered rather in the representation of physical, bodily presence of people (as well as in the repercussions of such presence in the viewer/artist), but while we are looking at representations of Jacqueline Roque, for example, we may also recall what Picasso-biographer John Richardson has said: that Picasso also chose Jacqueline as his second wife in the end, because he knew that she would care for his oeuvre. After his death. Which she did. And we realize that the concept of sustainability, the thinking beyond one’s individual death, was not at all absent from Picasso’s thinking.

(Picture: Juan Pablo Zumel Arranz)

Renaturalization:

(Picture: nzz.ch ; Nightnurse Images AG)

(12.-13.11.2022) Snapshots from Switzerland in 2022: a renaturalization project from the Zurich region, with a visualization that seems to promise a gain in urban lifestyle. While at roughly the same time the comeback of the wolf results in a tense atmosphere in the Canton of Grisons. With a visualization of wolves’ eyes lurking and lighting in the dark.

If sustainability means to secure a future (as we have defined it broadly), various strategies might lead to that goal, going along with various iconographies: there is the iconography of a smart management of resources, according to the classic idea of sustainability, which is: do live on the interests, not on the capital (do cut some wood, but not the forest; do shear the sheep, but do not skin it). But this classic core strategy goes along with other strategies: be prepared for dire conditions (the emergeny stock in households has become an issue in 2022, in view of possible energy shortcomings during the winter of 2022/23), and: do, perhaps, also build back structures that actually prevent a living according to the principle of sustainability. Since it is the bad conscience of people, a collective, socially constructed bad conscience, that seems to think: here and there we, our civilisation, has gone too far, progress has exaggerated progressing, and now it might be about repenting – building back, and about (partial) renaturalization. And this is what links the aforementioned snapshots: renaturalization does mean to think of a past state of things, and about, partially, replacing current states, according to a vision of past states. This is renaturalization, and also renaturalization does have a history (we think back of Rousseau, perhaps), as well as it has an iconography. And this is what this presentation is about: the present iconography of renaturalization.

One) Renaturalization of Landscape

I have briefly thought about if there might be a link between the one obsession of Paul Cézanne, his bathers, with the above shown picture. Which is a visualization of a renaturalization project at the Limmat, near Zurich, with – also some bathers. And if there is link, what might be it?

What I am thinking is that Cézanne had seen representations of the idea of a Golden Age in painting (for example such by Ingres), and his obsession had to do with his personal vision of such Golden Age. Which I would define as: being relieved from inner tensions in life that have to do with one’s relation to one’s body, which, again, has to do with bodily norms in society as well as with the demands of gender roles, as well as with the order of gender in general. And while attempting to envision his personal Golden Age (which had also to do with reminiscences of his own childhood and youth at Aix), his inner life does show to be partly relieved from tensions, but partly these tensions seem also to come through – while attempting to envision a more harmonious life of people – men and women – in nature, with nature, and with inner nature (while being individuals within social groups).

The link between the bathers series done by Cézanne and the above picture seems to be that it is about being relieved from something: a collective bad conscience, leading to partial corrections, for example, as here, renaturalization projects of communities, and, as far as Cézanne is concerned, inner tensions that might be more something of a personal issue, but have a social dimension as well, as far as the general relation of people with nature, and inner nature, is concerned. We see something that links the bathers by Cézanne with the above picture, but obvious are also some differences: a visualization study, linked to a renaturalization project, is not meant to do what art can do and be: to be researching into one’s individual relations with the world, with nature, with other individuals. But in both cases it is about thinking about how better states of things might look like in the end, about how more harmonious relations between humans and nature might look like, and about how better relations among people might look like. It is about partially building back and about renaturalization, but such projects involve – as the paintings by Cézanne do – a thinking about how to organize people’s life, in nature, in landscape, which includes also a thinking about how people might use natural resources such as landscape, such as a river. And we see little (except the rubber raft), in the above picture, that actually reminds of modern civilization (obsessed with tech; currently also obsessed with the idea, or at least the language of sustainability); and also the paintings of bathers by Cézanne simply spare everything that could disturb a harmonious state, as to the mere being of people in nature and among themselves. The bathers actually do very little, and also the above visualization is restrained as to what people usually do in nature, and as to how they actually live with and behave in nature.

Two) Reservoirs

Reservoirs are interesting, because they have become a symbol for smart resources management, for the use of renewable energies. But from a different angle, reservoirs can also be seen as a problem, as an obstacle to, perhaps, renaturalization or, at least, getting at a steady state of things, as to humans placing buildings into alpine landscapes.

And from again another angle one might say that, while bathers might be an embodiment of a harmonious relation beween humans and nature, with cyclopic reservoir walls we see humans commanding over humongous amounts of water (as Jahveh, in the Biblical account, commanded the Red Sea to divide), and although we might see walls without humans being present, we see the homo faber, the engineer, the Leonardo world (if one does like so, with humans creating the world anew, according to their purposes) behind these walls. – And still reservoir walls can be seen as an embodiment of sustainability and be included into a review of the imagery of sustainability, if perhaps with a note as to their ambiguity.

What has been a surprise to me, is that a Swiss Sunday paper has also declared reservoir walls to be a symbol of Switzerland per se, perhaps rather referring to checks and balances in the political system, perhaps also referring to the sort of resources management which is possible in countries such as Norway and Switzerland, with many reservoirs to gain electric power (the example shown here is the Grimselsee.

(Picture: Schölla Schwarz)

(Picture: painting by Luca Giordano)

I am thinking that, perhaps, in the year of 2022, we may have seen, or at least sensed, a shift in collective mentalities. The question of energy supply has been, in the past, perhaps rather a question debated within expert circles. The majority of people, I am including myself here, could take it simply for granted. Now that we have, at least theoretically, been confronted with facing shortcomings in power supply, and with the question of storing an emergency supply in our households, we might have won more of an awareness as to the rudiments of modern civilisation, the problems linked to our energy supply, and the patterns of our consumption of energy. I have looked at reservoir walls with new eyes, as well as I have looked with new eyes at Cézanne (using a viaduct near Aix as a constant motif in his landscape paintings). And if we will not experience shortcomings in the coming winter, it will also be due to an energy mix that includes a rather large amount of renewable energies. No building back here, but rather on the contrary: with the current trend being to progress with numerous projects that, also, will be affecting alpine landscapes, but aiming, in principle, to extend the amount of energy won by hydropower as well as solar energy.

Three) The Comeback of the Wolf

The comeback of the wolf, perhaps it is necessary to say, has nothing to do with urban lifestyles, although, not long ago a wild animal paid also a visit to the city where I am living myself: not a wolf, but at least a lynx, and virtually everybody, at least from my generation, might have been reminded of a famous story by Franz Hohler, named Die Rückeroberung (›The Reconquest‹).

Renaturalization, of course might make sense in urban areas. It is usually praised for improving the chances for a more diverse population of animals and plants. And people might also be relieved from a certain bad conscious as to the relation of humans with nature, if seeing the coming back of the wolf in certain areas. But history reminds us that humans had once been relieved to see the wolf disappearing, and now, today, it is about the question of how to manage this relation: between humans and the wolf.

This question we will not discuss here, but perhaps it might be useful to see renaturalization as a more broad phenomena with the needs of an more urban population on the one hand, and the needs of rural civilization on the other. There is a sociology of renaturalization, and then there is the imagery. And this is why we are opposing images here, images of the Limmat, partially renaturalized (I recall also having heard not only the aforementioned story by Franz Hohler at school, but also the more heroic tale as to the Linth-correction, which, again belongs to the Leonardo world, with engineers fulfilling spectacular promises of what men can do), and images of the wolf. And it is about the eyes of the wolf, because it is about the question: how close do humans want to live next to the wolf? And because the journalist who reported on the situation in the Canton of Grisons in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (Simon Tanner), did the illustration to his reportage himself: with many pairs of eyes, eyes of the wolf, lurking and lighting in the dark.

(Picture: nzz.ch ; Nightnurse Images AG)

(Picture: nzz.ch ; Simon Tanner)

(Picture: Martin Mecnarowski)

Rubens on Sustainability:

(Kermess pictures: collections.louvre.fr)

(10.11.2022) This picture (in the Louvre) is unusual. It does show the usual ›Rubens action‹ – usually stacked into one narrow frame –, but here the usual ›Rubens action‹, vital, muscular and fleshy human activity, is confronted with an open space. Human action is being relativized by a more open space, by a hilly landscape that seems, on some level, to represent a boundary, a frontier seemingly intimidating human activity to exploit that space (and be it simply for a rural kermess). And still, the people depicted seem to dance on that edge and towards that edge.

We see two sides of Rubens here, the vital Rubens, the embodiment of human vitality, and we see the landscape painter. And then there is another Rubens here, a Rubens that seems to think on the relation of human vitality – in view of nature and spaces. In view of nature, relativizing and, perhaps, restraining, human vitality. And Rubens is best, at least in my view, if he is restraining his own vitality, in the service of something that is more, than mere vital bodily activity.

The picture seems to depict a small corner of the world. But still a variety of human behaviour and experiences can be studied: consumption, of course (and also consumption beyond measure). Flirting. But also jealousy. And particularly interesting are the people dancing. Because the impetus of dance, of people, collectively dancing can be seen as a collective dynamic that leads individual people to moving according to that collective movement. The dancers seem not to be keen to leave the one small corner of the world which they are obviously inhabiting. But they are dancing, in view of the fields, the hills, the sceneries of peasant’s life. A town, a small city can be seen, and urban space can be imagined. But the kermess takes place in one small corner of the world, away from urban life; a life that, certainly, has to be confronted in the next winter, when supplies have to be bought, and wood, for heating, will be sold to the city. But for the moment, the one small corner of the world does seem to be rather self-sufficient. At least for the moment.

In our days urban farming has become fashionable, and it is easy to imagine Bruegel as a critical observer of such phenomena. Local products are to be preferred, according to the ideals of sustainability. And one imaginary, idealized ideal might be self-sufficient rural life, perhaps as idealized as Rubens was capable of depicting it in his Farm at Laken. This pictures shows the iconography of sustainability as it is marketed today by eco-supermarkets, as well as it might show the utopia which we will recognize as a tech-free utopia, and not as an ecotopia, which would be a world not without tech, but as self-sufficient as possible, free of conflicts about ressources (due to general affluence of everything people may wish for).

The Kermess does not show the ideal. It shows the wishes of people as they are, and as they often remain unfulfilled. And the vision of a more urban life might be the ideal of some of the people here, perhaps anxious to one day leave the small corner of the world. By dancing towards something people later will be calling ›progress‹. While the ideal, today, seems rather to be a self-sufficient, more modest progress, or, in other words, in the jargon of sustainability: ›qualitative growth‹ and ›steady-state-economics‹. Might the people in Rubens have an awareness of the dialectics of progress? Perhaps, but perhaps not the people in the Farm at Laken. These rather seem to be happy in self-sufficient affluence. The people in the Kermess seem to be more realistically drawn people, which might not be living in self-sufficient freedom, but seem to face alternatives: between being disappointed, and not being disappointed, between looking for new horizons, and staying where they are. What these people perhaps are not aware of is that, in the distant future, one will think about also about ›rebuilding‹, ›restoration‹, even ›renaturalization‹. Perhaps the drinker is aware of it. Because the Kermess rather, not the Farm at Laken, looks at consumption, as well as at overconsumption. It does ask for the right measure, the right moment, the right opportunity. While the Farm at Laken exactly avoids to raise such question: by showing the one eternal perfect moment – when all seems to be looking just fine.

(Picture: youtube.com; ava beck bucket; @salidabooks)

Solarpunk:

(29.9.2022) It is Thursday, temperature is 20.4 degree, the gas price will go up by 45% by 1st of October here, our solar lamp (made in China) is functioning only every now and then (which has nothing to do with it being loaded or not), so: why not writing about the imagery of ecological utopia (as long as we have still power, respectively light)?

(Picture: youtube.com; Andrewism; source of image is unknown to me)

I remember than, in 1989, our history teacher wheeled a TV set into the classroom. Did we have a feel that it was about history in the making now, about the history of our time? I don’t remember that. Perhaps we were just teenagers, busy mainly with growing up; but perhaps, since I remember the wheeling of a TV set into the classroom, we had such feel, or it was just a mix of both. And since we were teenagers, it was our time.

In terms of art history, Solarpunk is art history in the making. It is happening just now, that people, interested in Solarpunk as literature or as a visual style, also define it as art (or as the crossing of art and politics). And one could say that Solarpunk is the actual iconography of sustainability. Since sustainability, the discourse of sustainability, includes a utopian element. It is about securing the future – which has to be imagined in some way. And this is what Science Fiction does, this is what ecotopian literature does, and this is what Solarpunk does. And this is why I am including a discussion of Solarpunk in the context of my art history of sustainability.

Solarpunk can be defined in terms of literature. This is also what most people do when defining Solarpunk. Often they start with saying that this is a subgenre of Science-Fiction-writing, defined, among other things, by its optimistic stance: because Solarpunk is the imagination of a sustainable future, powered by renewable energy, a future in which the energy problem is solved and only renewable energies are used.

I have browsed the Solarpunk anthologies (which include also some art), and I cannot confirm the idea that Solarpunk is offering an optimistic perspective only; it seemed to me that it is also, obviously also, about the fears concerning the future. And also about the fear that the future could bring rather dystopia than utopia.

Be it as it may, and I am interested in the imagery of Solarpunk here, but not only in terms of style, but also in terms of content.

It seems imteresting to me that Solarpunk has been defined as style (Art Nouveau elements, natural colors and so on), because this could be a sign of the times: that one does define styles rather than to work out a political utopia. Style comes first, philosophy later. And this can turn out in various ways: such styles can become rather regressive, in that there seems to be not more than design elements (some sound bites, stolen here and there, do not make an actual philosophy), but it can also become quite progressive, in that the combination of design elements (the single elements do not exist for nothing), can inspire (new) political and philosophical thinking. Perhaps – let’s be optimistic – philosophy indeed comes later.

And, let’s be honest, Solarpunk is, in many ways, not really new. It is up-cycled Ecotopia plus star architects.

Ecotopia was the title of an iconic novel by Ernest Callenbach and did influence the utopian thinking, the ecotopian thinking since the 1970s. Henning Ottmann, in his formidable – formidable! – multi-volume history of political thinking, included a discussion of the novel, and Ottmann seemed to be rather amused than impressed: as far as the politics, the economy and the society of the ecotopia described in that novel is concerned. Not actually something based on woke philosophy, to be honest! In terms of artistic production rather egalitarian than liberal (no star architects, this means, and actually not artists at all, because excellence of individuals is not wanted).

And all the questions raised, concerning Ecotopia, can also be raised concerning Solarpunk: what way of solving conflicts will the future, as imagined by Solarpunk writers and artists, bring? Will there be artists at all? Obviously there will be technological gadgets, because Solarpunk as well as Ecotopia, is technology-friendly. But it seems, especially in pictures, technology is often rather hidden in much green, suggesting that one can have the iPhone, but one does not tell the children that it cannot be harvested from kitchen herbs! Could it be that there is also the danger of greenwashing inherent to Solarpunk? Since one does know that, for example, vertical-forest-scyscrapers are actually not necessarily in harmony with the ideals of sustainability!

(Picture: Shiny Things; Gardens by the Bay, Singapore)

Much of Solarpunk imagery, as far as I can see, is what one clever individual on Tiktok (@salidabooks) described as ›building a sustainable world on top of the one that did not work out‹. Because we see futuristic cityscapes, we see architecture which is simply overgrown and thus delved in green. And indeed a retro element comes in by much Art Nouveau (solar panels may represent the new).

But the question remains (also as far as images are concerned): is this more than just a re-combination of design elements? In some way it is: solar power, at least, does seem to work, and philosophy might come later, the philosophy of actual utopian thinking which does spell out the nature of that future. One does want it to be sustainable. But how to reach that goal? Also this question had also been raised by Ernest Callenbach, who, during the 1980s, published a prequel to Ecotopia, about the emerging of that steady-state-society.

›Aesthetics is not enough‹, as another clever individual (on YouTube) did put it. But an actual utopia of Solarpunk has not yet been worked out, it seems to me. Ecotopia might have been lacking the design elements, but in terms of raising questions it still offers more to think about that most of the Solarpunk imagery does (I am not speaking of the literature here, which I have not systematically studied). But as I have said: it is art history in the making. Vincent Callebaut might be the architect of Solarpunk, in that his architecture does seem to comply with what Solarpunk writers and artists seem to strive for. And we will have an eye on what comes next.

PS: I have tried also to prompt the artificial intelligence called Craiyon, to make a painting of Solarpunk in the style of Pieter Bruegel. This did not work out very well. But I may come back to that some other time.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS