M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

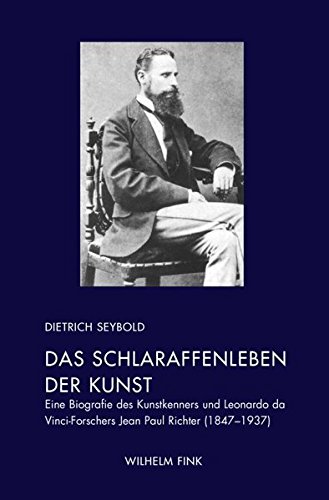

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

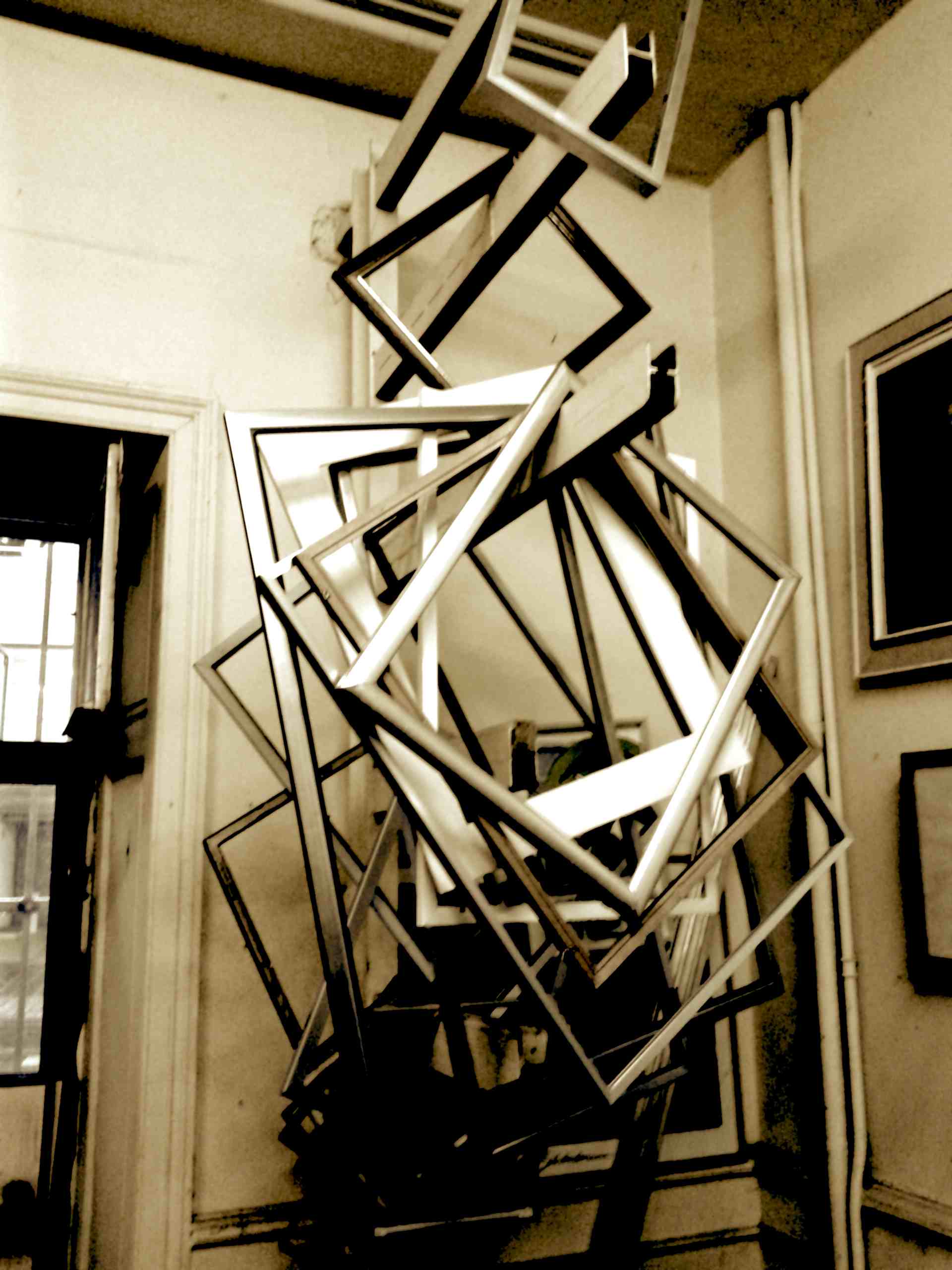

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

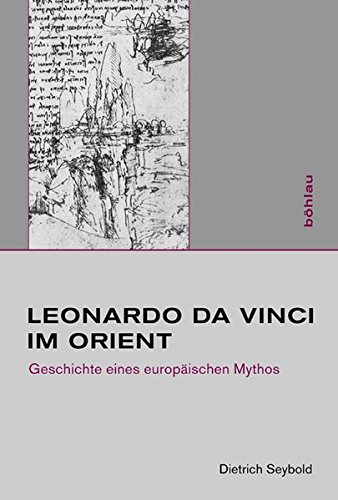

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

Dedicated to The Woman in Picasso

The Woman in Picasso…?

(23.3./3.4.2023) This is not another gallery of Picasso’s female companions, no, this is something completely different. I am asking: in what terms might Pablo Picasso have reflected on sex and gender, in, let’s say, the years 1947 up to his death in 1973? In other words: this is another exercise in biographical writing, a genre that I have recently invented. Do you know the answer? Perhaps your answer will be: in terms of the Marquis de Sade. And then I will say: Good answer! But things are probably a little bit more complicated. We will have to discuss literature, but what we will find is also a strange little discourse on the woman in Picasso (not in his work, no, the woman in Picasso, the man), a discourse that goes back to Jean Cocteau publishing a book in 1947, a book which established this discourse, which Picasso, on his part and as we will see, enjoyed and knew. Yes, Picasso knew this discourse! Furthermore: also Picasso’s female companions knew this discourse, and further: even Picasso’s acquaintances (like Francine Weisweiller) knew this discourse. There was a discussion about the woman in Picasso, in Picasso’s circle and with Picasso, and this is what we will look at and discuss here, not actually with the intention to give a final question to the aforementioned question, but with the aim to come a little bit closer to an answer.

1) What is a Discourse?

I am using the notion of ›discourse‹ in a very concise way here: a discourse, here, is simply a way of speaking about certain things. This may sound banal, but it is not. A way of speaking about certain things, such as sex an gender, always, due to a specific vocabulary and a specific imagery being used, allows to reflect on certain aspects of these things, but this does not say that every aspect of the things talked about gets revealed and highlighted. No, a discourse is always also a way of not speaking about certain aspects. A discourse also encompasses silences, gaps, voids and vacancies. And if Picasso may have found it enjoyable to participate in a discourse dedicated to ›the woman in Picasso‹ does not say that he may have revealed in what terms and how he actually might have reflected on sex and gender (although he may have had an imagery and a vocabulary for that, and although this vocabulary that he may have revealed in his art and translated into his art or not, might have drawn on literature and particularly poetry. There is no doubt that Picasso, it is well documented, also had a sadistic side; and this sadistic side is not talked about in the frame of the discourse about the woman in Picasso; but this is just another reason to be cautious and not to rush into conclusions.

No, the woman in Picasso (stills from Paul Haesaerts’ film Visite à Picasso (1948), as used in the documentary Pablo Picasso & Françoise Gilot. »Die Frau, die NEIN sagte«, Annie Maïllis (dir.), France 2021, with Picasso painting on glass)

2) Where and Why did Jean Cocteau establish a Discourse on the Woman in Picasso?

In 1947 writer und multi-artist Jean Cocteau published a book that was and still is cherished by many: The Difficulty of Being is a collection of autobiographical essays. And it is a beautiful book, a book of magnificent, sensitive and original prose. Jacqueline Picasso, who also got to know Cocteau better than many, did like the man, and she did, as it is also known, particularly like this book. And in this book, in one of the essays that make this book, Cocteau developed his idea that Picasso was actually made of two human beings, a woman and a man, brief: that Picasso was actually a couple:

»This complete artist is made up of a man and a woman. In him terrible domestic scenes take place. Never was so much crockery smashed. In the end the man is always right and slams the door. But there remains of the woman an elegance, an organic gentleness, a kind of luxuriousness which gives an excuse to those who are afraid of strength and cannot follow the man beyond the threshold.« (from the English edition, published in 1966; translation by Elizabeth Sprigge; I have used the German edition, for which see reference below)

One has to know that Cocteau was, to some degree, obsessed with Picasso, and that he took every opportunity to develop ideas on Picasso, to explain Picasso (to himself or others), and, on some level, to experiment with ideas on Picasso and to test these ideas. And this was a way, as we have to observe, to start a discourse on ›the woman in Picasso‹ in 1947. Simone de Beauvoir had not yet published her seminal work The Second Sex, and we have to note that, since a discourse never exists on its own – there are other discourses, other ways to reflect on sex and gender, and discourses have a history, appearing and disappearing, gaining influence or losing influence again, and discourses only exist as long humans are willing to use them, to live with them, and, in some way, to live in them. And this is also what we have to observe here: that Picasso and his circle lived with and in the discourse on ›the woman in Picasso‹.

In 1947 Picasso was in a partnership with Françoise Gilot, but this does not say that she was the only woman in his life. The idea that Picasso’s life can be organized in periods that are named after his female companions is decidedly too simple. Beware, biographer, of that idea – it does completely mislead you and makes you blind for much that happens in Picasso’s art, and the idea that he worshipped one woman only and exclusively is a little bit naive, but a beautiful romantic fantasy, which does not say that it never may have happened, but every ›period‹ in Picasso is more complicated than that! The idea that there was one woman that exclusively fascinated and dominated Picasso is an idea that goes back to a woman, respectively to Dora Maar, and John Richardson did like her idea that everything changed in Picasso with the woman changing that was at his side, and he did find that idea amusing and repeated it whenever he could; but Richardson knew very well that things were more complicated: in 1947 Picasso was in a partnership with Françoise Gilot, yes, but his wife Olga was present to some degree in his life, Dora Maar was present to some degree, as were other woman, and instead of dedicating periods of Picasso’s life exclusively to a respective female companion a biographer has to observe who was present at what time and how. And often Picasso’s art is reflecting several woman being present, and also the rivalry of woman being present.

This excursion on the women in Picasso’s life is necessary to understand in what way the discourse on ›the woman in Picasso‹ got spread and existed from 1947 up to the period of Picasso being married to Jacqueline (who was a reader of Cocteau). Because Françoise Gilot knew of that discourse and participated in it (for example in 1955; see C IV, 245 (12 September 1955)), but also later referred to that discourse, for example when being interviewed, much later, by Arianna Stassinopoulos Huffington, or for her book, by other researchers).

3) To What Consequences?

Thus the discourse on ›the woman in Picasso‹ originated in 1947, but it also can be traced: if Françoise Gilot could say to Cocteau in 1955 that he was always speaking of Picasso as a couple, she must have known this discourse for long, probably because Cocteau had not only started that discourse by writing in 1947, but because he was also a well-known and brilliant talker and raconteur, and constantly tested his ideas and theories by telling them to others. And it is also Cocteau’s diary that reveals that particularly in 1956, one did talk about the ›woman in Picasso‹ in Picasso’s circle, and that Picasso talked about ›the woman in Picasso‹ with Francine Weisweiller, a woman whose protegé Cocteau was at that time, and this talking about the ›the woman in Picasso‹ also got back to Cocteau, because Weisweiller, obviously, told Cocteau that Picasso found that Cocteau was right in finding also a woman in Picasso, and she seems to have reported what Picasso had said (for example that he was ›an old lesbian‹, because, actually, he liked woman – as well as he was made also of one), because what Picasso seems to have said found its way back to Cocteau and also appears in his diary (see C V, 195 and 198 (27 and 29 July 1956); Picasso used the old slang word ›gousse‹ for lesbian: see 198).

As we have to know, Picasso was in the habit of speaking half-jokingly and it is a big mistake to take seriously what he said all of the time, without being aware that, often, he did speak half-jokingly, a way of disguising – or telling – that he did actually refuse to have fixed opinions on things, rather playing around instinctively with ideas, and also with words, according to the situation.

But in 1956 he seems to have conceded that the woman in him was actually prevailing over the man (C V, 195 (27 July 1956)). And 1956, at least as far appearance was concerned, can be named to have been rather a year of personal harmony. The turmoils were political, and Picasso was in love with Jacqueline Roque who had found her place in Picasso’s life, or at least was finding it. And Picasso seems to have ended his relationship with Geneviève Laporte, did resist the temptation to paint Brigitte Bardot, and only here and there seems to have mourned the end of his relationship with Françoise Gilot, or had aggressive outbursts due to her having a baby with another man. But on the other hand Picasso seems to have pressured the Leiris Gallery to end the contract with Gilot, and even if, on the surface there was harmony, the conflict was not over, and new chapters were only to come.

This is important to recall, since the discourse on ›the woman in Picasso‹ defines certain human characteristics as male and as female, and it is a traditional discourse in that it defines gentleness as female, and aggressiveness as male. When speaking to Cocteau in 1955, Gilot had also mentioned that Picasso had wanted her to read the Marquis de Sade (C IV, 245 (12 September 1955))), and it is well known that Picasso seems to have tested women in wanting them to read de Sade. But is is more important here to mention that Gilot seems to have refused to play that game, by simply stating to Cocteau that she, on her part, preferred (›was closer to‹) Laclos – which means that she simply was inclined to play another kind of game, but a game she played, indeed. And this is exactly what the lesson of this biographical exercise might be: to raise the question in what way to speak about Picasso and his relations with women and men. Because in naming Choderlos de Laclos, Gilot suggested simply another way, not actually refusing to speak about the sadistic side in Picasso, but in showing how another discourse could be started, that one could reflect on sex and gender also in other terms, in terms of the Dangereuses liaisons, and not only in terms of a discourse on ›the woman in Picasso‹, or a discourse on Picasso’s sadistic side. It is complexity that is needed indeed, in terms of a discourse allowing to speak about complex things adequately. And it is necessary to accept complexity in things, in life, generally, and in Picasso biography specifically. And Choderlos de Lacos might, perhaps, offer that complexity. So we might be inclined to listen to Françoise Gilot a little bit more, but not uncritically. And not without being aware that also the game she played, as well as the discourse she suggested may have had its gaps, voids and vacancies.

Further reading:

Jean Cocteau, Die Schwierigkeit, zu sein, Frankfurt a.M 1988 [1958; French original: Paris 1947] [see pp. 25f.]

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS