M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Views From the Nightside of Connoisseurship

Views From the Nightside of Connoisseurship

Not to be misunderstood: our virtual museum of connoisseurship here is not meant to glorify whatever is to be associated with connoisseurship as such. It is as much about addressing the nightsides, as it is about reflecting about what is good/useful/inspiring etc. about it. But it would be too easy just to name the conventional criticism about connoisseurship being corrupted by its association with the art trade or about being identical with snobbery/charlatanism/elitism etc. or about being associated, in times of war or revolution, with the looting of cultural heritage (instead of with the protecting and conserving of it). What we do here, instead, is to listen to a tradition of self-criticism of connoisseurship, to a criticism that was coming from within. Because connoisseurs had and have their wisdom and moral standards, too; and did feel at times ambiguous about what they were doing. And the most interesting point about this tradition is: whenever connoisseurs were feeling that what they were doing was not adequate in terms of adequately thinking and speaking about art – they thought about ways being more adequate, and in this very moments, when connoissseurs or writers writing about connoisseurship became aware of the nightsides of their profession or their subject – they thought about the brighter sides of connoisseurship and of other ways of looking at art all the more intensely. Thus: If we reflect upon the pain, the wrongful obsession, the disease or even the snake’s bite – we feel it worthwile to also name the remedies or, at least, what is known to us about such remedies, of antidotes and cures.

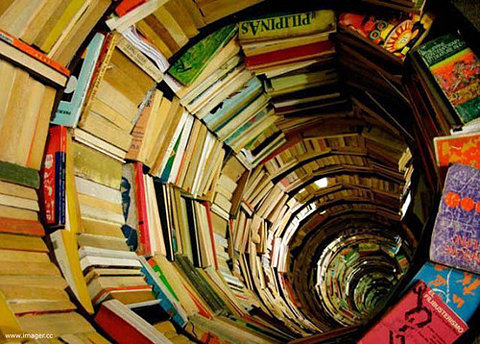

One) The Nightmare of Completeness

(Picture: bookbread.com)

Let us be brief here and do this in an aphoristic style, because this is of a wider philosophical bearing. To Berenson we owe a definition of the problem:

»Convinced on the one hand that to know all that at a given moment could be discovered in the exploration of this field, to know enough to be sure one was not humbugging, was a wholetime job; […].« (Sketch for a Self-Portrait, p. 44)

To know all and to know enough, regarding a certain task one has attached oneself, or that has become an obligation, while days are passing into the future. This is the scenario that every scholar of every discipline knows only too well. It is not even necessary to know to what »field« Berenson here is referring to (and our readers will have a slight incling anyway). To know all, understood in the very basic meaning of the term, and for just a second not yet understood in its meaning of being able to recognize (the German language knows the two verbs of »kennen« and »erkennen«).

But if we now go on to think of a little, but tricky attributional problem that we might encounter on our way of fulfilling the given task (let the task be here an oeuvre catalogue), we see how quickly the scenario might turn into something gloomier.

Because it is an obligation to fulfil the given task; our life goes on, and the little, but tricky problem suddenly shows as a problem that to solve travelling becomes necessary, or the checking of reference material not available to the public; and now the other aspect of knowing comes in: the knowing enough.

Since it is about comparative looking, there is potentially an infinite mass of reference material to be checked. And this far we have not even spoken of the microcosmos of connoisseurship – the world of the detail, as opposed to the macrocosm of the oeuvre catalogue or inventory.

Not to mention the meta oeuvre catalogue: the one oeuvre catalogue that might comprise all other oeuvre catalogues (which, of course, is philology’s mythology of the very Jorge Luis Borges-kind), but what, if someone like Bernard Berenson (who, in the above quotation was speaking about the drawings of the Florentine masters) envisioned an oeuvre catalogue of this particular school, a kind of meta oeuvre catalogue as the famous Berensonian lists are, in the end (for a second we might think here of the image transmitted maliciously by Kenneth Clark, of seeing a mass of photographs, assembled in a sunny garden site and still sticking to the paper due to glue, but photographs that may now begin to unroll due to the no longer sticking of glue…)?

It seems rather to be an exception that Berenson addressed the nightsides of his profession that directly. Few connoisseurs seem to have done that. And this probably because every scholar is aware or at least has made his or her own experiences with having to deal with a task given and the obligation to complete it (Berenson, yet, aims at explaining, that the whole turning to allegedly scientific connoisseurship had to be seen as the one wrong decision of his life, which made him spend ten years for something questionable, but we come to that kind of nightmare later). The situation can get easily out of hand, on the side of the knowing it all, or the knowing it all enough. And if it does, nightmarish scenarios might be the consequence. The material to be checked amounts to mountains, the macrocosm opens to astronomic dimensions, not to speak of the microcosm, that world of the nit-picking, hairsplitting, cross-sectioning of problems. And the overall goal: getting something done, to know something completely and having it worked through satisfactorily (»to be sure one was not humbugging«) shifts out of reach. The purest form of a serious scholar’s nightmare. But now, inspired by the Anatomy of Melancholy (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Anatomy_of_Melancholy), we come to some remedies known, possible cures and antidotes to that particular snakebite: the obsession for or the nightmare of completeness:

(Picture: risorseutili.com)

Remedies known:

Cult of the fragment; aphoristic style, exemplary dealing with a chosen problem; delegation of that problem to others. Think also of an (imaginary) Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works. Wise men of all times have known that it is more fun to have ideas than having to work them out (but make sure to think of this while completing the dictionary).

A Berensonian strategy (as alluded to in his Sketch): have others do what you only lay out as a possible path (if enough others are around). Or (a more Borges kind of strategy): Find yourself settled within the library of Babel, i.e. the meta oeuvre catalogue: to know all might not even be impossible (this leaves you with a humble attitude: philologists, and also philologists of the eye, are meant to die over compiling the volume covering the letter L of their famous Wörterbuch), but the being settled within one niche of the library might even be fun (it is however necessary to regard the very idea of completeness of whatever kind as a demon that easily can be neutralized (neutralize it within a footnote, if necessary).

A Morellian kind of strategy: never do something close to the completion of an oeuvre catalogue, a guide or a list anyway; limit yourself to an attacking of the buildings erected by others and above all do this in an chaotic and unsystematic style. If you come under attack yourself of, for example, not being »scientific«, claim that what you do was never meant to be scientific anyway (but keep on thinking about the building of a future science of connoisseurship that way, that futher generations might be rife to erect and to complete). Further: do seek help to complete any book that you seek to complete in that style. Whining might not win time, but maybe improve chances of getting better funding (if necessary) or human support.

Berenson was whining despite reasonably good funding (but it was about principles here). Last but not least: do question the very idea that connoisseurship is or should be scientific altogether (while it is reasonable to live on the idea that others may have made of your being a scientific capacity). Never do associate the very idea of connoisseurship with the very idea of system (this is the very demon whose heart a stake has to be driven through). And let us finally mention the Jacob Burckhardtian love of the scientific (as opposed of the not-loved »strictly scientific«) and quote the aphoristic Max J. Friedländer (scholars have observed that his style of writing developed more and more towards an aphoristic style, this is just another way of diagnosing the problem we have dealt with here, but Friedländer was perhaps one of the connoisseurs most aware of these remedies needed and also someone capable of getting 14 volumes things done anyway, in sum, a role model, if one would be looking for to find some):

»The connoisseurship of art is not a science, and be it only for its nurturing of its man, which is something that decent sciences do not do.« (Aufzeichnungen und Erinnerungen, p. 20; translation from the German: DS)

..........................................................................

Two) The Ludicrousness of Pedantry

(Picture: politicsforum.org)

Here we take the opportunity to point again to the one particular irony of the history of connoisseurship that consists simply in the fact that Giovanni Morelli, who has become one embodiment of the obsession for detail, for the most pedantic procedures of attributing pictures, relaying on the observation of the minutest detail, actually most deeply hated to be overly pedantic.

Which is to say that he, of course, got entangled with problems of attributing and that he named ways how to possibly raise a level of certainty as to the knowing the authors of pictures, but – at the same time he felt most deeply that he had gotten entangled with something that was actually in conflict with his own nature and his self-image. And the more he practiced connoisseurship himself, and the more it did lead him to practice minute observation and got him also involved in heated controversy (which he actually did like more), the more he got aware that one side of this profession of connoisseurship, a profession he had never actually chosen (but the profession found him), was pedantry. And he was not a little concerned not to got entangled with pedantry more than necessary (the square of the circle of connoisseurship, one might say, and to some degree he did enjoy also the comedy of his and other connoisseur’s constant manoeuvering). In brief: He was only too aware of the danger of being seen as overly pedantic, and to be identified with the ludicrousness of pedantry. Posterity did identify him as a close relative of Sherlock Holmes, and Morelli got away with it that one side of the scientific connoisseurship he had imagined and inspired himself was actually pedantry.

How sensitive Morelli reacted to this danger can yet be shown in quoting a passage of a letter to his (even more pedantic but less talented) apprentice Jean Paul Richter, dating of 1881. Richter’s brother Max was a medical doctor aboard of a ship at that time and had just called on his brother Jean Paul, and on occasion of this visit Jean Paul had also told Max of the momentarily ongoing controversies between Morelli and the connoisseur faction of Berlin, as to the attribution of certain drawings. Morelli, who obviously felt and showed a certain uneasiness, replied:

(Picture: likeashot.tv)

»Thus you have recently had the joy of seeing your younger brother again and to have him with you for some time –, yes, you have had him even join the rapier fight between me and the Berlinese fencing master. Yet such a fight about drawings may seem somewhat pettifogging and pedantic to someone who does sail from the shores of Java to the distant California. Yet these are the fruits of Old Europe hyperculture, recalling the Greek times of Lucian and the likes.«

At the time Morelli did associate his own doing with the writings of Lucian (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucian) – as we have mentioned earlier, Morelli loved this kind of satirical writing – he had long left behind what once had been a passion: the studying of comparative anatomy. But even if we go back, we find this Morellian being averse to everything that requires pedantic discipline. And we may recall one of his closest friends here, the artist Bonaventura Genelli, who had heard that »Freund Morell« was about to give up scientific studies altogether to become a writer, in saying in a 1844 letter that, indeed, it was a strong imposition of this science of comparative anatomy, if it did take one five or fifteen years to find out something about a maybug.

Still from the 2009 Effi Briest movie (picture: kino-zeit.de)

It was the German novelist Theodor Fontane (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodor_Fontane), however, who had an excellent sense for issues of connoisseurship, to give one of the most striking images of not only ludicrous but also tragic pedantry, and this some years after Morelli had died, and just at the time, when Morellian connoisseurship was probably at the height of its popularity, but this is more coincidence and has little to do with the kind of pedantry shown here: In Fontane’s novel Effi Briest (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effi_Briest ; published as a book in 1896) the parents of the main character, young Effi, get letters and postcards from Italy, where Effi, now married to Baron von Instetten, spends honeymoon with her pedant husband (in a way, and significantly, this pedantry reveals on that trip to Italy). She has to listen to her husbands explaining of art (she naively even reports to her parents that her husband likes it quite well that she has hardly any knowledge of that kind to offer). And all Fontane needs to foreshadow where this marriage is leading to is one or two pages of showing the Briest parents receiving these reports from Italy and of displaying how the parents react to these. In fact the whole drama that unfolds could be enfolded from just the old Briest’s very words:

»Effi is our child, but since October 3 she is Baroness of Instetten. And if her husband, our Herr Schwiegersohn, wants to make a honeymoon trip, and if he wants to catalogue every gallery anew on this occasion, I can not prevent him from doing that. This is actually what one calls to marry oneself.« (translation’s mine; a short rapier fight with his wife, about what »to marry oneself« means for a woman at the time, follows as a consequence, but ends with the famous words »Das ist wirklich ein zu weites Feld«, as spoken by the old Briest)

Remedies known:

The 2009 movie (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effi_Briest_%282009%29) has Effi apparently not die of broken heart (as the novel has it), but to develop into being an independent woman, who chooses to work as a librarian and might have lived, if not happily everafter, at least contentedly. Other remedies (as recommended by this Effi as well as by Giovanni Morelli): reading of Lucian (but without pettifogging commentaries by philologists), Lucian, who, by the way, is one of the inventors of Science Fiction. If Lucian is not available, a good rapier might do.

............................................................................

Three) The Pretension that there is Ultimate Certainty

One particular interesting phenomena within the history of art is the phenomena that people laugh at pictures (or other works of art). While this laughing might mean: ›a child of six could do this‹, in connoisseurship another laughing might exist: a laughing at pictures, saying: ›who was foolish enough to attribute this painting to this or that painter?‹ And we see that this laughing at pictures is rather a laughing at those who gave certain paintings certain names (those who criticize do also speak of an »imposing« of certain paintings to certain authors, of »assaults« on those painters, respectfully, and of those people committing »suicide« that are to be held responsible for certain attributions).

Examples of this kind of laughter might be rather sinister cases of people, by laughing, hiding inner insecurities. By overly exaggerating an ostentative certainty as to the being wrong of others. Pretension combines here with, or even melts into illusion as to ultimate certainty.

(Picture: hyperallergic.tumblr.com)

When, as mentioned above, the Morellian way of addressing problems of attribution was at its height of popularity at the early 1890s, everybody felt that there was a promise of, possibly, a new level of certainty within reach as to the attributing of pictures, and thus a promise of a way of determining things. Possibly ultimately so. One of the major auction houses had an auction catalogue made by Morelli’s pupil Jean Paul Richter, and the pictures of a particular collection reattributed according the new scientific standards (and one may call this, in retrospect, a test, as to how things might be going in the future).

But this particular sale in 1895 ended with a notorious disaster, the so-called »Doetsch-disaster« (named after the collection being sold), because of the new standard not being accepted by the London art world.

The interesting thing, however is, that the preface to this auction catalogue indeed speaks of scientific ambitions as to the attributing of pictures, but the rhetoric, even as early as 1895, or already in 1895, was less than boasting, the preface only claiming that the pictures »owe their names to something more consistent than chance and more solid than fancy.«

Something more consistent than chance and more solid than fancy?

(picture: universal-prints.de)

While this might sound rather modest by standards of today, the art world at the time might also have thought that the pretension by the Morellian school was much bigger than it actually was. At least on this particular occasion, and when being that exposed. But it is a paradox to observe that those who cared for a scientific standard that was meant to improve things, over time bitterly lost their illusions as to the dream of ultimate (or at least a higher level of) certainty. Berenson, in his old age, mocked the »German« pretension of »objectivity« as such. long after having spoken that what was within reach in connoisseurship was »at best« plausibility. And this, again, long after having claimed, in his youth, i.e. at the very time when Morellian thinking was at its height of popularity, that the new science of connoisseurship, given that photographs were used, »almost« would reach the accuracy of the physical sciences.

(Picture: kultup.org)

Remedies known:

To milden the consequences of errors due to own pretensions and illusions: If you happen to use a particular method as to the attributing of pictures, any method of whatever kind, claim that it leads, at least in 80% of the cases, to sound results. If errors occur (and cannot be covered up), explain that it might be due to a) not having applied your method, b) due to errors committed only while applying it (due to exterior factors), or c) due to false premises forced upon you by someone else. Especially in the latter case, it is helpful to point out more specifically that your eyes had only been awryly »prepared«. If it is yet still your personal error that is spotlighted by others, point to the long history of collective illusions. This history might be too painful and to disillusioning to be written upon sound principles of historical writing, but it crystallizes in tales like the one of the Emperor’s new clothes (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Emperor's_New_Clothes). This tale, on its part, can be traced back to the Middle Ages, namely to Muslim Spain. If you need a story that more specifically deals with art (and with ignorance as to the perception of art), you may check a Till Eulenspiegel tale (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Till_Eulenspiegel), that has, instead of non-existing clothes, non-existing pictures hanging on the wall. This tale, on its part, can be traced back as far as to the Medieval German author named Der Stricker (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Der_Stricker), which is to say, to the 13th century. – If you happen to be confronted with the pretensions of others, just use the wisdom compiled here invertedly.

Since Giovanni Morelli is conventionally seen as an embodiment of positivism, we would like to give him here a chance to refute that conventional claim. Yet in our view two hearts were beating in his chest, that of a positivist and that of a deeply sceptic constructivist, who got a perverse delight out of testing, if he could pass, for example a painting, for something else than it actually was (and at least once this joyful doing had the nightmarish consequences that I have attempted to lay out and to explain in my paper on the so-called »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«). Thus I would suggest to take it with a grain of salt, if Giovanni Morelli, in 1888, was writing to his friend Austen Henry Layard:

»If I have been concerned with ancient art, and this with a patience and persistence worthy of approbation, this is because it has given me personally a great deal of pleasure – but that my intellectual diversion will provide a great service to the so-called truth – this thought did never cross my mind! What do we know, poor creatures, of the absolute truth? Few things, actually, since the knowledge that we manage to attain down here is only fragmentary and yet very imperfect. Thus we have no reason at all to pride ourselves on it. Amen!«

(Source: Carol Gibson-Wood, Studies in the Theory of Connoisseurship from Vasari to Morelli, (great book of) 1988, p. 286f.; translation from the French is mine)

............................................................................

Four) The Taking the Blame for Errors Committed by Others

(Picture: zeno.org)

Giovanni Morelli once referred to his doing as a critical connoisseur in terms of an »egg dance«. By which he meant that he was, when critically writing about the Berlin gallery, carefully avoiding to touch the sensitivities of the various exponents of the Berlin museum world.

As said above: what Giovanni Morelli says has, often, very often, to be taken with a grain of salt. And here I would go as far as to say that Morelli tended to do exactly the opposite of what he claimed. Maybe he was, when writing about the Berlin gallery, doing an egg dance (as the picture given above shows it), but if so, then he was doing an egg dance that was meant to touch every sensitivity possible (and to destroy as many eggs as possible).

As it is well known, Morelli had chosen Wilhelm Bode as the main target of his attacks, and I mean this very literally: Morelli had chosen Bode (and not the other way round, because Bode, on many occasions actually tried to become friend with Morelli, but this did upset Morelli even more…). Which resulted that Bode had, and he complained about this several times, to take the blame for all errors (or seeming errors) committed by any exponent of the Berlin gallery, responsible for any attributions displayed in the Berlin gallery catalogue. In German there exists a beautiful colloquial idiom for this: one does hit the sack, meaning the donkey (›den Sack schlagen und den Esel meinen‹). Someone gets beaten, for errors commited actually by someone else, and this happens, hopefully not as often as one does imagine, in connoisseurship, a field of practice that is inhabited by many individuals – but it does happen that these individuals assemble as a group (for example around an outstanding individual), and the result may be, as it was at Giovanni Morelli’s times, that one does speak of »the enemy’s camp«, referring to another group, possibly assembled around another outstanding individual.

If now Wilhelm Bode got beaten on a many of occasions – some Morellians however preferred to think of Bode as a »clown with a club« – this happened because, in Morelli’s eyes, many donkeys were around, and Bode, again in Morelli’s eyes, represented the stupidities of a many of these donkeys (I won’t name any of these here).

On the other hand, horribile dictu, it did happen that a Morelli pupil trumpeted out publicly one of Morelli’s opinions as to the attribution of certain pictures, and Morelli got into danger of actually getting beaten for his real opinion (that, wisely, he had not been trumpeting out, since he knew of the many sensitivities, not only of his enemies, but also of his many friends). And it also did happen that Morelli got beaten for just having appropriated a certain opinion of some of his mentors, that himself, after some time, considered as being wrong.

And the uncritical appropriating of Morelli’ seeming opinions (as mentioned above, sometimes he played a little around to test, if people would believe what he was saying or better: freefully and joyfully inventing) could actually lead to the beating of people, who had committed no other error, after all, than of having had too much respect for one authority’s opinion for to challenge this authority’s opinion critically and on one’s own part and responsibility.

By the way Giovanni Morelli referred to the doing of art historians once in terms of the parable of the blind leading the blinds, and he did this by referring to the Brueghel painting shown below. We take this, again, with a grain of salt, since, as might have become clear, the parable’s content could be illustrated not only by telling anecdotes about the »enemy’s camp«, but very so in telling anecdotes (we won’t spell out any of these here) about the Morellian »camp«.

Possible strategies (which one to choose will depend upon your own preferences):

First of all: keep the pictures shown above in mind. Secondly: If it is absolutely necessary to join a group, think carefully about which one to join (or, if you are a cynic, you will join all the parties, to win all the advantages possible, but keep in mind that this requires constant manoeuvering and you may be, as it were, beaten in the end with stick and club, because the opposed parties melt in considering you as the only enemy). If you feel that opposed camps seem to want to win you as their respective ally, stay in touch with any of these groups while not joining any of them. Very important: Keep all the letters coming from any party – since posterity will regard your archives as particularly precious as to the history’s of connoisseurship battlegrounds. Last but not least: provide you with a club (for safety reasons), because someone may come to claim his or her letters back. Most important: hide these letters well, you may even forget about them, but do not prevent posterity from finding them.

.............................................................................

Five) The Nightmare of Having Chosen a Wrong Way

A more precise idea of the status that cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt had among his contemporaries we get from reading the letters directed to Burckhardt. Strangely enough that only now these letters are being published and made available to the public online (see: http://www.burckhardtsource.org). Among these letters we find one of Burckhardt’s student Gustav Schneeli (http://www.kunsthausglarus.ch/frontend/exhibition_detail/315), writing from Munich in 1894 and seemingly a little worried, if what he was about to do was really the right thing. Apparently Schneeli, who also was a painter, used Morelli/Lermolieff as his textbook at the Munich gallery, and maybe even so advised by Burckhardt. And dilligently the student, as he told his Professor in this particular letter, did compare and did make his notes, and also did compare his results with those Morelli/Lermolieff got to on his part.

»Übrigens ist es beinahe comisch; über irgend ein Bild von untergeordneter Bedeutung so viel zu schreiben, wo doch des

Sichern u. Herrlichen so viel da ist. Ein grosses Verdienst Morellis liegt aber gewiss darin, dass er den Glauben an all die den Bildern angehefteten Namen erschütterte.«

(»It’s almost funny, by the way; to write a great deal about any picture of subordinate meaning, whereas there is as much that is ascertained and glorious. But certainly a great merit of Morelli lies in his having unsettled the faith one had in all the names attached to the pictures.«)

Die zwei Wege (picture: lebensmut.wordpress.com)

But Burckhardt, at Basel, knew this doubt, this feeling that the very specialized connoisseurship, mainly aiming to certify authorship, was a little narrow-minded (Morelli, by the way, knew this only too well himself, as we have pointed out above, and the connoisseur Morelli is simply that side of his nature that got known to the public and to posterity).

Morelli once had visited Burckhardt at Basel in 1882, and after having spent time with Morelli Jacob Burckhardt had embarked on a trip to various German galleries. In the end he was to write an often quoted elegy referring to Morelli also in a rather sarcastic way, and making a point about leaving Morelli/Lermolieff now in his suitcase, but unread. But what is less known is that Jacob Burckhardt had, on this very trip to Germany, quite enjoyed to pose, inspired by Morelli, as a connoisseur and to confuse people with his connoisseur opinions, people that eagerly had awaited Burckhardt’s opinions and had thought him to be rather on their side.

What Burckhardt actually had in common with Morelli was this waggish sense of humour. And if he did play the connoisseur’s role on his trip (or at least telling his friends so, in his letters) he did not mock attributional connoisseurship as such. Because Burckhardt felt a certain passion for questions of authorship, and was concerned about them, only not to the degree that a dedicated scientific connoisseur was or was meant to be concerned about it. It was a question of balance and of the right degree of attention or of the quantum of time to be dedicated to such questions. Being stricly scientific, as we have mentioned above, was not what Jacob Burckhardt did like. And if Burckhardt was less a scientific connoisseur in the strict sense, he was, if appreciation is the other side of connoisseurship, all the same an embodiment of connoisseurship.

But still we see his own student, Gustav Schneeli, with Morelli/Lermolieff at hand at Munich in 1894.

Burckhardt was aware, and we know this also from browsing the letters directed to him, that even among the dedicated followers of Morelli were some that at some point had had really enough of being involved in heated controversy. And it’s interesting to imagine what Jacob Burckhardt had though if he had heard Bernard Berenson loathing himself for dedicating years, even decades of his life to something that one part of Berenson considered as something rather trivial: questions of attribution – the nightmare of having chosen a wrong way, but realizing it too late.

Remedies known: the best possible remedy of which we know of is to think of connoisseurship in its best moments. We’ll speak about that in the future, and within some other section, but what we mean is: when in does not exclude every other meaningful way of doing art history or of dealing with art, but does encapsule every possible other way. Because the trying to determine authorship implicates the question: what does it actually mean to know an artist and his work? Is it only about knowing a formal repertoire? Or isn’t it much more about a knowing of a particular artist’s personality and of his intellectual and social world, not only of his formal, but also of his intellectual decisions? Of his sense of humour, and of his way to see the world?

And in that discussing authorship is only one step away of discussing artistic individualities. And if questions of authorship are discussed on such a level, everyone, who has ever been involved in a case study or has undertaken one himself, knows: connoisseurship can, in its best, in its most passionate moments, be one of the most intense ways of dedicating one’s time to artistic things. When it is not primarily, paradoxically, about the final attribution for the main, but about all the questions raised along the way that can possibly sharpen one’s perception as such, for works of arts and for artistic personalities as well or in particular. And in its best moments connoisseurship is about the being as close to art as one can get (if one is not doing art oneself).

Back to the starting page of Dietrich Seybold’s homepage: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/HomePage

© DS