M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

MICROSTORY OF ART ![]()

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

Dedicated to Richard Serra

Of the place where I live, just outside the gates of the city of Basel, I have three works by Richard Serra within walking distance. One, Intersection, has been a matter of controversy in around 1992. It’s the one I can reach in about 25 minutes, but this is not the one I am mainly interested in right now. Another one cannot be visited, because it is housed within an industrial area not generally open to the public. And the third, the one that I am dealing with here in the following, is Open Field Vertical/Horizontal Elevations (for Brueghel and Martin Schwander) of 1979/80 at the Wenkenpark of Riehen.

As the Basel Programmzeitung has written, only attentive flaneurs take notice of this work, as it were, immersed into the landscape. And in that it does represent the other extreme as to the destiny of works of art in public space, while Intersection (as also the Programmzeitung has written) today is »more tolerated than appreciated«. I can reach Elevations in about a two hours walk and, to begin with, it is an interesting question, if this would make sense. Would one do a two hours work to get to a work of Brueghel that only could be experienced there, at Riehen, Wenkenpark? Certainly, one would. But to take a stroll that far to mainly think about the quaint dedication of this Serra work – »for Brueghel and Martin Schwander«, is another matter. We’ll see if this makes sense. But it is also a stroll to Brueghel and, as usual, to a couple of other things.

With this contribution we open the Microstory of Art Online Journal whose two godfathers are two art historians that particularly have thought about the detail, Giovanni Morelli and Daniel Arasse, who also represent a particular attentiveness to detail (Giovanni Morelli, by the way, did like to take long walks as I do, but if both art historians would have joined me on my mission, I don’t know). What I am intending to do with this journal is to experiment with new forms of essay writing, cultural journalism and scientific publishing. The journal will be dedicated to art, connoisseurship and – cultural journalism, and it does look at the world from Basel (and from times to times at art at Basel and also, like in the following, the near surroundings).

A Landscape Piece or Looking at Brueghel with Serra

A damp day with clouds from white to dark grey. Some spotlighted from somewhere and therefore bright white, but all hanging low. A damp day in summer, after much rain had be falling. In sum or étants donnés: ten forged steel cuboids, certainly very heavy, due to their high density, a landscape park, few people, and dampness, which is to say – the very day. And, not to forget, a visitor, interested in all this.

How to approach a landscape piece? Or are we rather to say: how to enter a picture? Is there a main entry? Or are there many alternatives? And not least: are there any rules at all to this?

Yes, there are, because space is full of rules. Traffic rules, for example, and rules, legal and moral, as to the respecting of property, of not entering private ways, for example, and there are quite a few. Elevations, however, can be approached from various sides (it is legally possible, it is probably even wished so by the artist, but – as a bird, unseen by me, flew away with an extraordinary yelling, when I was about to enter a side path – I do imagine an unseen exotic bird of extraordinary colors, but I do also feel sorry –, it is not necessarily wished so by the animals). Still there is only one point in space at all, where the visitor is explicitly hinted to the landscape piece, its creator, its title, its date, its material, its owner, its (or one of its) inherent ideas. But what is being written remains partly mysterious. Above all the dedication. »für Brueghel and Martin Schwander«, it says, on the outdoor museum’s plaque, but the typography does not make clear, if this seeming dedication is to be meant to be a part of the piece’s title or not. Actually it is only part of the German title, the translation, given underneath the English title, but on the other hand: the line with the dedication begins with a small letter, which probably means that it is part of the full title, at least in German, and the dedication is not being given in parentheses, after all.

Compiling of information might lead to a false lead, but still an interesting one: a Martin Schwander is more visible than another one, at least in virtual space (where the two personalities, by the way, partly have melted). Yes, the dedication certainly refers to the curator, art advisor and former director of the Kunstmuseum Luzern, but books on art are also (at least within the only Martin Schwander Wikipedia entry), attributed to another Martin Schwander, who, in the late 1960s became known as a figure of Swiss counterculture. While it is not altogether likely that Richard Serra did dedicate his landscape piece to this Martin Schwander, due to Serra’s political attitudes, it is not necessarily completely impossible, and if the still politically active Martin Schwander did actually publish books on art, it would become even more likely. But it has been made clear by Sam Keller recently that the Serra on the Basel Theaterplatz would not be there »without« Martin Schwander, who was present, when this statement was being made, because Martin Schwander, the curator, was meant to be Serra’s interview partner for an hour or so at Fondation Beyeler. And the bond between Martin Schwander, the curator, involved also in the 1980 exhibition at Riehen Wenkenpark, named Skulptur im 20. Jahrhundert«, for which the piece was made (it actually was a comissional work), has been a bond for quite some time.

Étant donné: a cuboid, only seemingly a cube, close to a park path, and belonging to a family of ten (picture: DS)

*

As far as I remember I did not attend the 1980 exhibition, but it is not altogether impossible that I was there. For my family had just moved to Basel at the end of the year 1979, and maybe – but I do not recall – we made a visit on this occasion at Riehen, Wenkenpark (for Wenkenhof and Wenkenpark see here). I would not be surprised if pictures would come up with me and the Serra (or other works of art), but I was only eight years old then and maybe interested in drawing onto pieces of our household’s furniture or on one of the many Picasso »coffeetable« books that we had (on one cartoon slipcase there is actually a drawing to be found that, however, I would date earlier, and also on the underside of a low living room coffeetable, where only children get to draw at all.

In brief: it is also a walk to or a visit at a site that has, at least for me and because of its date, a symbolical meaning. The Serra, it had no meaning at the time, settled there at the very time when we settled or tried to settle at Basel (broadly speaking, because we actually settled at Binningen, but this is, although its a different Kanton (Basel-Landschaft), also Basel suburb, while Riehen, politically, is a part of Kanton Basel-Stadt).

It, the Serra, has been there as long as I have been there (at Basel). And if it has come into age, I have come into age as well (although I had been eight years older then already). And although I don’t know if Serra ever has done a landscape piece within an actual border area, it is easy to imagine one cuboid on one side of an imaginary or real border, and another one on the other side. Not least because, if you look at the cuboids for some time, they seem to have their own character, not to speak of their own will, seemingly moving away from a place, maybe because of a border, pulling back from a centre of attention or striving to it (and one even wanting to slip down a slope).

And maybe they move like snails, but this I was not able to find out on that day in summer. In any rate: they are meant to make us feel and to explore space in that they invite us (everyone of them, because of everyone being an element within a structure) to connect them and to look from one element to another one, or to the other ones as a group; and if there were borders, if only in a children‘s game, you would feel the space all the more intense, and not only the merely topographical, geographical dimension of the landscape park, but also a political topography. Space Richard Serra does think sculpturally, i.e. as if it were material, and if you think space politically, sculptures that define space sculpturally would become or be political sculptures.

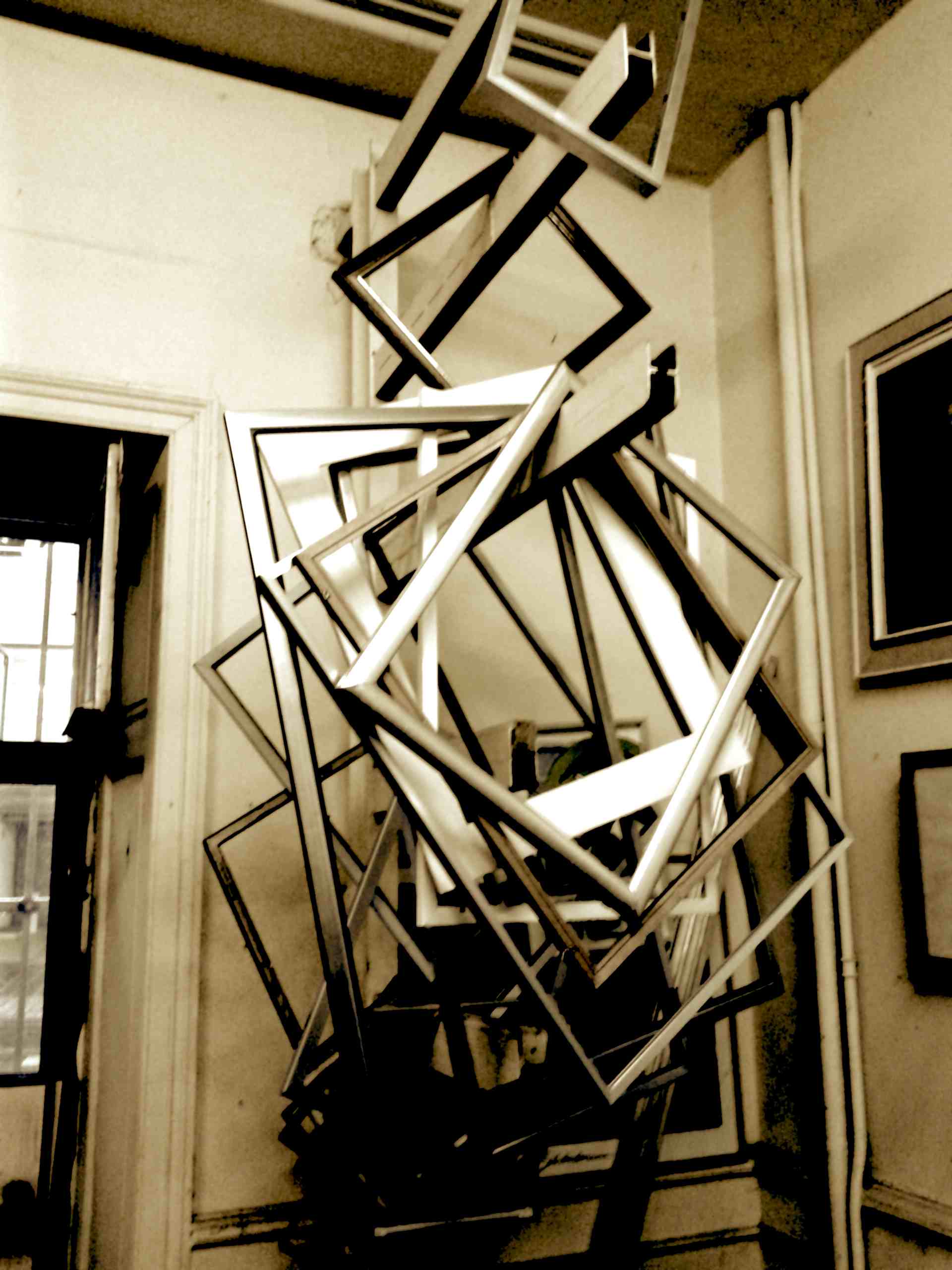

Thinking space sculpturally (detail from the Corn Harvest)

But this is not what I was thinking when being at Riehen Wenkenpark that day in summer, because the atmosphere, all the more so on a damp day in summer, with only few people on the park paths (and only one, in particular, and for mysterious reasons, leaving them), was a more peaceful, more detached, more introverted one, although it might be still the kind of day that you breed out more radical, more political ideas nonetheless. But for me it was a day whose atmosphere was probably best defined by musingly observing a man, being there with his dog, somehow and repeatedly trying to apologize to his dog for something that apparently had happened to that dog or would be happening to that dog. And if there were other people, few other people, they seemed to be musing too, and the only loud voices I heard that day were voices of probably two students, being there with one child’s cart each, discussing matters of completing some degrees. From what I say it is already becoming clear that the piece, at least on that particular day, was also about focussing one’s attention to what is going on within the structure set by Serra and within other structures seen and also explored. And Elevations, this is just one way to see it, could be interpreted as a mere grid or frame, or better: a cluster of frames, and invitation to think about frames of perception.

In sum, it was a day, where one’s attention could be drawn to basic things. To geometrical patterns for example that you are moving in, and the few people on the park paths, for some strange reasons, brought out this even more intensly. Because if there are only few people, and you are with them within the structure of a park (another artwork), your attention is drawn to them, to how they move, to who they are, to who they might be.

No people there with quadrocopters yet, that day. But if one would have wanted to take a survey picture of the park and especially of the section where Elevations has settled, not to mention a border area within or without a children’s game, this would be one of today’s possibilities: to have a quadrocopter with a camera attached to it, taking a bird’s eye picture or a series of pictures of Elevations.

Because there is no point in space, at least I did not find one, that offers you that view that one is, if exploring something, instinctively looking for: a tower, a rock, a higher level. What you get are partial views. And like the completion of a panoramic picture or a map, this completion happens largely in your mind. Or maybe, later, on a piece of paper or a screen.

*

I had only a vague idea that day, why Serra did dedicate this landscape piece to Pieter Brueghel (I imagine: to Pieter Brueghel the Elder, but the plaque does not make this clear either). When, earlier, I had taken notice of this work for the very first time, it had been the connecting of the site with Brueghel and Martin Schwander that had fascinated, puzzled, irritated me. Instinctively you look at the landscape theatre of the park, the groups of trees, the gentle slopes, but there are actually no »open fields«, as I would understand open fields to look like, and I did not see Brueghel either, strictly speaking. But you are, as often by works of Richard Serra, rather gently invited to do something: for example here, to think a painting by Brueghel that large size, that parkscape large size, or at least in relation to something large as this site. And you may think a painting by Brueghel as a real landscape with slopes you may, on a damp day, slip downwards. And with water in it, which is or appears to be as real, as drops of water that were still sticking to some leaves of grass that day. Instinctively you do project your idea of Brueghel into that landscape as well, and depending on the weather or the season, it might be a different painting of Brueghel, that, maybe, and as a child, you did encounter in form of sigsaw puzzle and therefore you do know quite well, especially as something meant to be explored in detail, something to be entered. And we realize that the mere associating of the site with Brueghel, invites you to look at the park landscape in a particular way. In search for detail, while on the other hand, you may want to look for works of Serra, or for comparable experiences that you just have made within the Serra, within pictures of Brueghel (including to watch other people, within pictures of Brueghel, making experiences with space).

(Picture: DS)

What Serra did, seems to be like what a painter does, when doing the very first steps of defining a composition with some marks. I did read only now that Serra did this, in 1979, with banana boxes first, but then Serra obviously did leave the way of what a painter (or a mere banana boxes artist) would do: by choosing his signature material, the forged steel, by choosing geometrical strict forms, that look as being opposed to the generally less strict shapes of nature, even within a landscape park (not the French garden of Wenkenpark, by the way), and by choosing simple forms as elevations, as opposed to the unpredictable moving of people and especially of groups of people and of large crowds; by choosing the more subtle strategy of positioning five cuboids vertically and five horizontally and, last but not least, by associating the piece with names like Martin Schwander and Brueghel (which is what a painter might do as well, but not the associating of names with a real landscape being part of a landscape piece).

I believe that the deeper meaning of this dedication is or was that Brueghel, like Velázquez, for Serra, when still trying to become a painter, meant a challenge. And, maybe together with other painters, the challenge that led Serra finally to give up painting for sculpture. Because, as he felt (he explained that in an recent interview), he could not think or make pictures that addressed and involved a viewer like a painting by Velázquez does. He could not do this by painterly means. But Elevations does, as I am describing here, address and involve the viewer in a gentle way, which makes me to rather prefer the notion of inviting, by the way. And maybe, as I imagine, just because a large landscape painting by Brueghel once did challenge (or invite) Serra to choose his viewpoint, to develop his attitude in front of it, to think of it as a landscape that – at least in imagination – could be seen from other viewpoints, i.e. from alternative viewpoints inside the very scenery –, in sum: because a painting by Brueghel did once invite Serra to enter it as a picture and to be part of it, by taking a stroll within, by joining this or that group of people, by taking a walk from this or that elevation to another one, – just for this very experience (that might have added to other ones) he was able, as an artist, to invite a viewer on his part to do the same thing, but by sculptural means and after giving up painting.

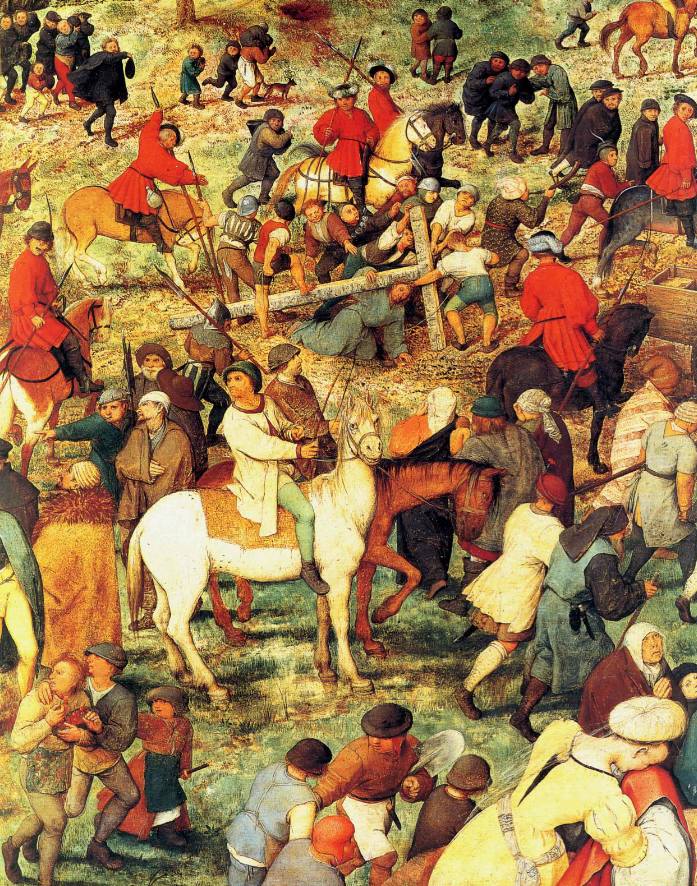

From the first moment of rethinking my personal experiences with Elevations, I thought of Brueghel’s rendering of the Cavalry mountain, of his Christ Carrying the Cross or The Procession to Cavalry. Because this is a scene that challenges you (to choose your attitude, speaking morally), that also challenges you as a landscape (because, for example, there are extremes of high and low viewpoints to be seen), and that also invites you, in a gentle Brueghel, and I may add, in a gentle Serra way, to enter the scenery like a visitor enters a scenery where the already assembled people indicate that something socially important is going on. You may enter the scene with more radical or more gentle ideas in mind (or with no ideas in mind at all); by choosing the main entry or the hidden entrance of a side path, by choosing you means of transportation, which is, by choosing the tramway to Riehen (and bus No. 32 to Wenkenpark), or a horse or a mule (if you have one), or your own feet, and by choosing to stick to the rules of traffic, by choosing to stick to the laws and rules in general, or not. Not least: by the way, as to conventions, that may turn to be rules as well, of how to look at pictures and how to look at art, and, if there are rules at all to be found, how to look at a landscape piece, and especially a sculptural piece like this one by Richard Serra. And last but not least: by choosing your own attitude towards of what you experience, politically, morally, and as a human being.

What I have chosen here is a way to look at art that has more to do with being amazed by the drops of water sticking to the leaves of grass that day, with being amazed by the geometrical shapes of hedges and by being amazed of a man repeatedly apologizing (or expressing his being sorry) to his dog, and this is exactly what I want to take with me, when looking at a Brueghel painting now in a fresh way: when bringing back and transmitting the experiences made with, and inspired by Elevations by Serra to Brueghel, to Pieter Brueghel. In one word, if looking now at Pieter Brueghel with Richard Serra.

The first thing that I had noticed when, while preparing for my visit, looking with only a vague memory of Serra at Brueghel’s Procession to Cavalry were the clear geometrical shapes that give the picture, although a scene of masses, a structure and your eye a footing. The cross (in T-shape) at the picture’s very center, of course, but also the geometrical pure shapes of the cart’s wheel, the spears, the windmill’s wings (again in T-shape) or the erected wheel (by which space within the picture can be thought of sculpturally, too, and maybe was thus seen by Brueghel). Further the elliptic shape, resulting from a circle of spectators, indicating, within the distance, the site where the executions are going to take place, and, as a particular sublety, the probably actually rectangular flag, that due to movement (of air or of the flag itself) shows as a triangular, arrow-like shape, indicating and underscoring the curve direction towards the execution site at Golgatha that the procession is about to take (and all the other movements and groupings of people can be seen in deliberate or not deliberate relation to that curve and to that chain of actions as anticipated and known by the Biblical narrative (which by the way, is not to say, that the picture would not allow or even comprise other narratives).

Geometry, dedicated to (or signed by) a Selina (picture: DS)

This was basically before visiting Wenkenpark again. And only after having come back from my visit, however, the bodily experiences added to the more abstractly seen, and this is something to be taken with us now, when entering a painting. While it seems to be of some danger to see (hidden) cuboids and geometrical shapes now everywhere, it is the real experience that adds to the already seen. The being focused to elements of a structure and to the relation between elements within space. It is the real life experience that there is geometrical strictness and simplicity, for example of traffic signs, and as opposed to the less strict (or more complicated shapes of a landscape). While there is no strict geometrical order at the section of the park where Elevations is situated, there is nonetheless order, too, and for example a basic opposition of those lawns cut and that left to be growing. The simplified shapes may represent order and simplicity, in opposition to the less culturally structured and more chaotic.

On a very basic level the Serra brought out, for me, the experience that we move in landscape while the experience of moving within landscape is basically determined and organized by this basic opposition as is the opposition of order and chaos, of cube and non-cube, of the spherical and the non-spherical, while the accidental form can also be thought of as being composed by the geometrical simplicity, so as a flow between the two extremes can be thought as well, and geometrical simplicity and bodily order within nature might be destroyed or eroded by time as the skull in the foreground of the picture is or will be. But to work with steel, on the other hand, can be interpreted as an attempt to oppose, what culture is able to oppose, to this future decomposition, and at the same time still to anticipate this future decomposition by various forces of nature. To think of all the people shown to us by Brueghel, as having some notion of this as well, or of having an even better grasp of it, or experiencing the same thing right now, appears to me now as one particular interesting way of entering the Brueghel painting, in that we do not project our experiences of exploring space into it, but in that we ask to what exploring of space the picture does invite us.

Geometry in beginning decomposition (picture: DS)

Exploring Brueghel with Serra (I): A Sense of High and Low

(Picture: mediavoiceovers.com)

»You know who does react to my sculptures most directly?«, Richard Serra did ask in a recent interview. »Children. They have no preconceived opinion about what they see.« And why not imagining of being standing on top of one of the Elevations cuboids, and to imagine of being observing what is going on on the ground, at the park, and to check, if one of your playfellows climbs on top of another cuboid as well, and by doing so, relates to you, like you relate to the other cube your playfellow is standing on and now to your playfellow, and in the end you may see your playfellow as a closer friend or suddenly as a competitor. This playfully exploring of objects and relations within space might end with a jump from the cuboid, with a more or less soft landing in the grass, with a fight or a hug, and in fact this playful exploring of a higher level of observation is of the very kind of my earlier looking for a higher level of observation. As before mentioned I did not find one that did allow an overview upon Elevations (and a quadrocopter with a camera was not at hand just now), but I did at least find a higher level of observation, literally and metaphorically speaking. And I have become curious, what levels of observation the Brueghel pictures might be rendering (and in rendering: offering).

One might realize only now that the Brueghel painting is full of extremes: a bird’s eye view is alluded to by the many birds. But the points of observation are manifolded, and from all this points within the picture you may draw an imaginary axe of viewing to one of the picture’s centers or to another viewpoint, and in that the picture offers endless possibilities of relating things, and Brueghel pictures do this anyway.

(Picture: artboom.info; picture processed)

The partial view offered to the viewer of the painting as such is, on one level, the privileged one, but there is no reason not to ask, what spacial experience the view from the windmill rock upon the scene might be offering on its part. There are many points from where the whole scene might be overseen, and at the same time there are many people rendered that have, at the very moment of time that is rendered, extremly limited viewpoints right now: the picture shows the limitedness of perception as such (although it alludes to overall views as well and actually does offer a wide view). For example by showing a child being concerned with not getting its clothes wet while crossing something like a stream (it is water within the picture as well, but as to the stream it is only a partial view that is offered to us, who don’t know exactly from where it is coming from and where it is flowing to). Another children being focussed while exercising riding or while being concerned with completely other things. Because of being a child and living in childhood dreams, or because of being concerned with how to get something done. Or because of being concerned with how to get the best view upon an execution (which might be one of the most brutal insights into human nature that the painting might offer at all, that human nature, if it is free to choose or not, allows empathy, represented by the Pietà group at right foreground, as well as it allows indifferentness and voyeurism). And one might say that the Serra invites you to visit and to explore a structure every day, because every day what you might experience within the structure of the artwork that it is not thought to be as being pictorial as such by the artist, becomes pictorial in a different and unexpected way; the Brueghel on the other hand offers a limited multitude of things and endless relations between things and aspects of things that to explore a lifetime might not be enough. And another modest, but not actually trivial insight might be, that while the Serra anticipates a »loading« of the landscape piece with personal experiences of various kinds and of different viewers, the Brueghel in a way anticipates the reducing of an infinite number of relations to be drawn between elements, and here it is about a viewer’s choice, ableness and will. And both approaches implicitly, for as long as the two works of art do exist, thus do implicitly address the notion of infinity.

The Brueghel painting, by the way, has recently inspired a movie that apparently explores the lives of chosen protagonists from within the painting; the Serra on the other hand, after having explored it for a while, recalled my watching of the first series episodes of the TV serial Lost, and especially the one episode where a mysterious hatch made of steel is being found on the island where a group of survivers of a plane crash explore what it means to survive and to maintain or to create or recreate civilisation. This might be just another scenario of popular culture TV serials, but actually it is nothing but another scenario of a children’s game, and thus another way of exploring objects and relations of objects within space. A invitation to think of subterrenian structures within the Serra or the Brueghel landscape piece. Because the cuboids remind of mysterious objects, to be found on mysterious islands, and the site of Golgatha, outside of Jerusalem, might actually have been connected with the very city of Jerusalem by means of tunnels. Such subterrenian structures apparently exist, but of course Golgatha is not a place that has been geographically located as one specific site within the surroundings of Jerusalem. But while if it might be more natural to look for higher levels of observation, it may worthwhile as well to think of subterrenian structures and of what connects the society at view within the landscape with the city and no the least with its structures of power. And within children’s games, cuboids may become treasures, mysterious extraterrestial objects, a chance to step upon a pedestal, a chance to hide behind it and thus, since to hide is only one step away from disappearing, to enter other, for example subterrenian worlds. In sum: why thinking the relations between the cuboids as relations seen and as relations above the ground? They might as well be seen as elements that are connected by a subterrenean structure, and in fact they are: because the configuration of the elements, the placing of objects within certain, exactly defined measures – this is one idea the museum’s plaque refers to – for the artist had to do with the landscape’s topography and its measurements, i.e. with its downward gradient. And it may enough to point here to the question why and how the various objects seen in the Brueghel picture are actually there where they are (for example the stream).

(II): In and Out of Frames (Forbidden Ways, Diggers and Secret Entries)

(Picture: lescaret.blogspot.com)

One element of Elevations is actually placed very close to a small passage already outside the Wenkenpark. It’s the one cuboid that is placed higher than all the others. And it was probably this cuboid, which almost seems to slip down the slope and thus alludes to the fragility of the piece and to fragility as such, also because, in a bright night in fall of 1985 (by that time and now a teenager I had seen the Brueghels at Vienna), apparently this very cuboid almost did crush a teenager, being part of a group of teenagers that tried to dig a hole underneath the cuboid, for the cuboid to disappear (and surprisingly for the group, the cuboid did actually slip). Samuel Herzog, the art critic of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung did publicly recall this episode in 2010 (see here), interpreting the acting of the group of teenagers also as an unconscious fulfilling of their parent’s wishes as to the Serra (and one might be tempted to think about what the children and teenagers are doing in the Brueghel picture in relation to their parents wishes, and to see a picture in terms of being loaded with such wishes might be another way of seeing a picture anew).

It is obvious, if one explores the site that the particular cuboid is very appropriate for such a nightly attack, because of its being close to a public way, that is, however situated in a neighborhood of villas, private gardens, private walkways and, as Herzog did allude to, probably guards with dogs.

We are exploring space at the very margin of the Wenkenpark, searching for other entrances to the park and also the picture of the landscape piece that we load with our experiences. And in doing that we make a stroll through a neighborhood where making a stroll is already something else and at nighttime might even be under suspicion.

But if we enter the park, following a legal way into it, we suddenly face views upon elements of Elevations that we now see, having only halfway followed the the path, being hidden by bushes and lowly hanging leaves of trees. The repoussoir scenery we show here also in a photograph shows thus the unseen entering of a picture, while it is not being totally clear where the picture actually begins. In any rate we explore the feeling of being at the margin, of hearing loud voices within some distance, voices of people that do not actually see us, and that we do not see neither. Again space, that organizes socially around the elements of Elevations, turnes into something else here: a scenery of potential secret observing, of voyeurism and of pulling back, because it does not seem decent to surprise people, that actually might actually being discussing private issues. The cuboids now appear as aims, that are, because of our pulling back, outside our reach. Space has been structured because of social rules of politeness, of respecting privacy within the public space, but without the cuboids it would be just a matter of being polite, and with the cuboids it is something that leaves a mission of getting something or getting to something actually unfulfilled. And again one may asked of by what social rules the Brueghel picture is loaded of (and of what secret entries it does speak, of if it even does render space turning from something into something else, even if the making of experiences is something that unfolds within time and human activities that unfold within time have to be rendered indirectly within pictures).

(III): Spacial Iconography of Noise and Silence

(Picture: DS)

Detail from The Procession to Cavalry (source: artboom.info; picture processed)

It’s another interesting question if the Brueghel picture shows people actually pulling back within all silence from the scenery. It does show musicians, or at least one musician. It does show human conflict, horses, groups of people, but the painter offers such a vast view, that it is possible to think of that, at the margins of the high plane of Golgatha, we would also be noticing such pulling back for whatever reason (for example to come back better equipped). Why should all people strive into the picture’s center of attention? There might be people, completely realizing what is going on in all its implications, unwilling to become involved. And the rendering of such characters would require the visually rendering of doing something – unnoticed by the group – in silence. To steal away from the what is happening, to deliberately turn one’s eyes away, or, to whatever reasons, to turn one’s eye to something, and again swimming against the stream of people. Silently taking a glimpse with whatever consequence.

Noise and sound, less in terms of commanding, of giving military signals, might be another challenge in terms of how to render pictorically. But the very sight of a child hiding behind a cuboid would be associated with silence, of wishing to remain unseen and, to the aim of remaining unseen, to remain unheard.

On the other hand: while being hidden by bushes and leaves of trees, I did hear voices, and why not imagining visually depicted people, that seem to be half hidden, of hearing things. And why thinking that the Procession to Cavalry shows largely people without empathy? And one would again be tempted to look at the picture in search of people indirectly showing empathy (possibly combined with indirectly showing of being powerless).

(Picture: artboom.info; processed)

Damp grounds, by the way, can be thought of being particularly noisy. And the cart wheel, that is shown as already being muddy, might inspire to actually hear sounds instigated by the merely seen, and one may finish by asking if this picture By Brueghel is a particulary loud or silent one. And again it would be about choices about what to perceive and what to leave out of consideration because the yet limited number of elements allows an infinity of possible relations and interpretations of that relations. The Serra landscape piece, is a work of art that you experience depending on a day’s atmosphere and depending on what comes through you, as a result of what you might be able to perceive of what you wish to perceive and what you don’t. There is little preconceived, as, probably, in a painting of Brueghel much less is preconceived as one would think. At any rate: As a result of looking at Brueghel with Serra, I feel inclined that Brueghel, would he have been interviewed, might have said something comparable as – it’s children that react most directly to my paintings. Because they have not preconceived opinions about what they see.

Postscript: The great connoisseur Max J. Friedländer considered Aldous Huxley’s short essay Breughel, that was published within Along the Road of 1948, as »in its whole perhaps the best that has been written« on that master.

Huxley’s essay can be found here.

and we finish with quoting Friedländer: »He [Huxley] calls the master an anthropologist and a social philosopher. I would say: connoisseur of human nature, expert of his countrymen and contemporaries, poet of tragicomedies, wordly preacher, humorist.« (Erinnerungen und Aufzeichnungen, p. 32)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

A gloomier side of the day: view from inside the park upon the panorama terrace of Riehen Wenkenpark on the other side of the Bettingerstrasse (picture: DS)

Taken on occasion of a later visit in September… (picture: DS)

View upon the entry of Riehen Wenkenpark from across the Bettingerstrasse with the panorama terrace behind you (picture: DS)

© DS