M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Study

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY CABINET IV: Mouse Mutants and Disney Cartoons or: Reinterpretations of the Morellian Method  (Picture: disneyclips.com) |

We discuss various representations of Morelli here in this chapter. Knowing that from early on Morelli had known something of representing people. Because during his studenthood not a few Munich artists had actually made portraits of him (used also throughout this monograph).

Some of which had become his friends (like Mende and Genelli); while at least Wilhelm von Kaulbach, who had also represented him, was later not much liked by him (and we don’t know if this also does apply to Kaulbach’s portrait of Morelli).

While we thus may assume that Morelli must have had at least an intuitive and physical feel of how artists imposed their habits of the hand and mind upon the image he yet had of himself, we may also assume that this is one experience – being the sitter to a portrait –, among many other experiences to which the originating of his connoisseurial thinking might traced back to. And we may say that he did never stop to think about how and why artists left their individual imprint as artists upon representational form in art.

But we know also that Morelli did like to play with representations of himself, that is with outer appearence, and we have to stay aware that Morelli might not have liked static representations of him. But rather causing a little confusion here and there. By making for example people believe that he had been a sitter to Genelli’s representation of Prometheus, which is probably not true, but just an invention.

And thus we have to remain critical as to any representation of Morelli (or alleged representation), and stay in the habit to critically compare the most diverse representations of him. Which is what we do here, focussing in particular on representations of his method.

ONE) GIOVANNI MORELLI SEEN THROUGH THE EYES OF… (I)

CABINET IV: MOUSE MUTANTS AND DISNEY CARTOONS OR:

REINTERPRETATIONS OF THE MORELLIAN METHOD

(ONE) GIOVANNI MORELLI SEEN THROUGH THE EYES OF… (I)

(TWO) MOUSE MUTANTS AND DISNEY CARTOONS

(THREE) GIOVANNI MORELLI SEEN THROUGH THE EYES OF… (II)![]()

›After all you do hold my knowledge and expertise in all too high esteem and indeed would like to turn my little person into a grenadier. My vanity, by this, yet does feel very flattered, but does still not prevent me, though, from thinking of Icarus’ fate.‹

»Sie hegen überhaupt von meinem Wissen und Können eine viel zu hohe Meinung und wollen durchaus aus meiner kleinen Person einen Grenadier machen. Meine Eitelkeit fühlt sich dadurch zwar sehr geschmeichelt, hindert mich aber doch nicht, an das Schicksal des Ikarus zu denken.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 17 November 1879 (M/R, p. 91); from Milan)

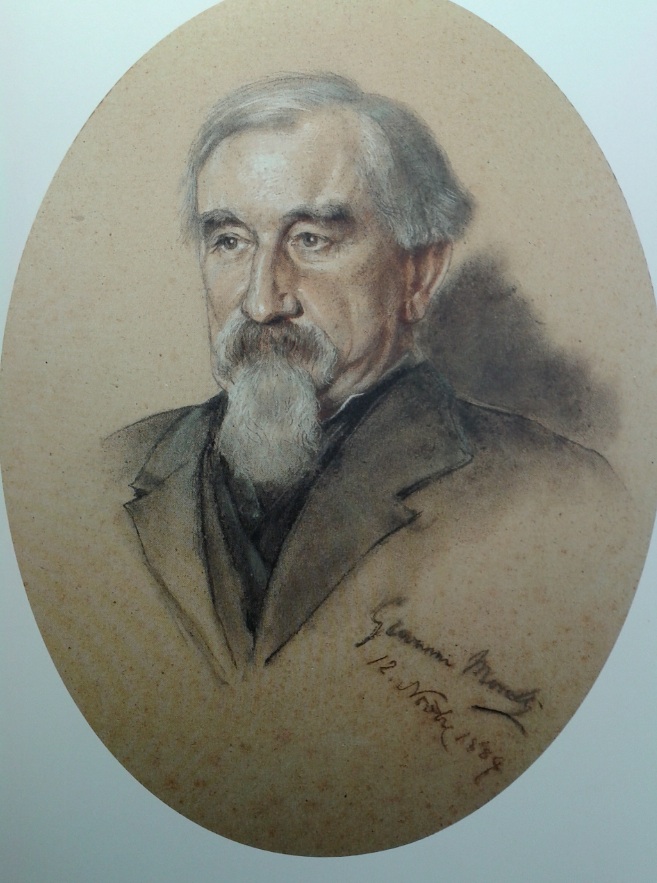

During his lifetime only few people knew Morelli as posterity is used to see him: showing a more disgruntled face, showing an apparently more morose character. And it does not surprise that those who knew him from close, felt slightly puzzled by the two Morelli-portraits by painter Franz von Lenbach. This was not the Morelli they knew (and Lenbach, without any doubt, had actually gotten to know the more cheerful Morelli as well). This was not the hilariously cheerful Morelli, known for his distinctly waggish sense of humour. Much loved for being not only cheerful, but warm-hearted, and for being attached to his relatives and friends. And little surprising: those who really knew him were able to see the smiling eye only in the much lesser known portrait by the Prussian Crown Princess Victoria (small picture on the right).

This would not present us with a problem, if posterity would know or had remembered that the two Lenbach portraits do show a rather rarely seen Morelli, in that they do show an apparently less well-humoured Morelli. And not to be misunderstood: a gloomier side did exist as well. Morelli in fact had a, if much less seen, gloomier side, could feel depressed, momentarily, if for example suffering due to his recurrent bodily ailments, and saw everything, as he put it himself, in a gloomy lighting.

And during the last decade of his life, the smile from his face, speaking figuratively, disappeared more often. His polemicizing turned to be rather stereotypical. The playfulness, occasionally, seemed gone, as seemed, at least for moments, his irony.

And his more stereotypical polemicizing, if only being read, if being read without recalling an impression of an generally smiling eye, reads rather grim. In the end, at several occasions, the warmth, the deep affection, the compassion that Morelli had shown throughout his life, a compassion he was radiating, and also and maybe particularly after having harshly criticized some of his antagonists (which is: feeling sorry for having critized them all too harshly), seemed to have left him and gone. What remained were, sometimes, metaphors of war. And Morelli, in the end and occasionally, indeed seemed to fight against, to polemicize against shadows, as the clear-sighted journalist Sigmund Münz did put it once (Münz 1898, p. 89).

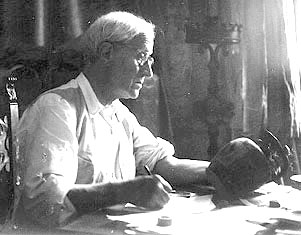

Giovanni Morelli (sitting, on the right) looking over the shoulder

of Colonnello Guicciardi in 1866 (source: Bora (ed.) 1994, p. 82

(only detail from original photograph being used here))

On a more metaphorical level, it is not only the smile of Morelli that posterity did not and does not recall: it is the whole complex of his life that had to do with the genre of comedy. And much of his life had to do with comedy, and many years of his life he had cherished the dream to become a playwright and to present Italy with a new comedy.

Because with this, at least on some level, Morelli did fail, he did not like to remember this other passion of his life: the passion for the theatre, the comedy, which, in later years, showed mainly as a certain flair to occasionally turn into an ironical and also dialogical style of writing, when writing about art.

But compared with his earlier, hilariously-burlesque letters to his friends as the Frizzoni brothers, or compared with the quixotic adventures that Genelli got to hear and read about – his art historical writings read somewhat tame. One does still feel the impulse, to turn into, to unfold more burlesque scenarios, but one does also feel the restraining impulse: this all had also, somehow, to fit into an image of someone suggesting art history and particularly art connoisseurship to become a serious science.

Posterity, in a word, did struggle to unite this various impulses within one image of a man, as Morelli had struggled to unite these various sides of his character in his person. His sceptical side with the more optimistic and enthusiastic side. And what had helped him to unite both was irony. Because irony could relativize: relativize the all too serious (and systematic) positivistic claim, but also the temporarily felt all too deep abyss of scepticism. Abbreviated by the thought that everything, everything, and also the project of turning art history into a science, was mere illusion and in vain.

But on the other hand it is also ironical that a sort of copyright was given to Morelli by posterity, a sort of copyright as to a connoisseurial working with formal analogies as such, a copyright as to a rigid study of form in works of art. As if such a tradition had not existed prior to Morelli entering, late in his life, the stage of European art connoisseurship.

And such a tradition had also existed, rather independently, next to Morelli: Ludwig Scheibler, for example, who had studied under Carl Justi, and, for some time, worked under Bode at the Berlin museum, was thought, by Justi, to have worked – as did work Morelli (see Carl Justi to Jean Paul Richter, 26 December 1889, Bibliotheca Hertziana). Using his eyes to spot formal analogies. As earlier had Carl Friedrich von Rumohr, and many other a connoisseur of art. Even in the 18th century, And beyond. But still, and this also might be seen as a distortion of a historically balanced image of Morelli: after Morelli – almost every style of close observation was associated with him, could be associated with Morelli. And this probably due to his one feature that singled him out, made him different, if compared with other also rationally working connoisseurs, aiming at rational explanations of what they had found by intuition (thus making, intuition and find, verifiable and falsifiable).

This one feature, this one single trait that singled him out had been that Morelli, publicly, and in his specific and also ironic way, represented the claim that art connoisseurship should or could turn to be organized based of scientific principles, and he had represented the ambition to carry out such a project, fostered by a tool such as the Morellian method, even if his doing had not resulted in getting very far, as to the more broad ambition.

Still it is possible to assemble traditions that trace their own pedigree, more or less, back to Morelli. Such a tradition in the field of archeology and the study of ancient art deserves mentioning (see Beard 2002; Agosti/Manca/Panzeri (eds.) 1993, vol. 2, pp. 399ff., pp. 409ff.), although or because, in this very case, it is not always stated very clearly, why actually the working with formal analogies should be traced back to Morelli only (and not, for example, also to Rumohr, Lanzi, Bottari etc.). And why not also to the more broad ambition to institutionalize the rational approach to connoisseurship (for example being represented by Rumohr), beyond a mere ad-hoc applying of it.

This Morellian tradition in archeology is certainly outshadowed by the main tradition in art history, represented by no other than Bernard Berenson. And the question if, and to what degree, Berenson is actually rightly seen to be the one representative of a Morellian tradition.

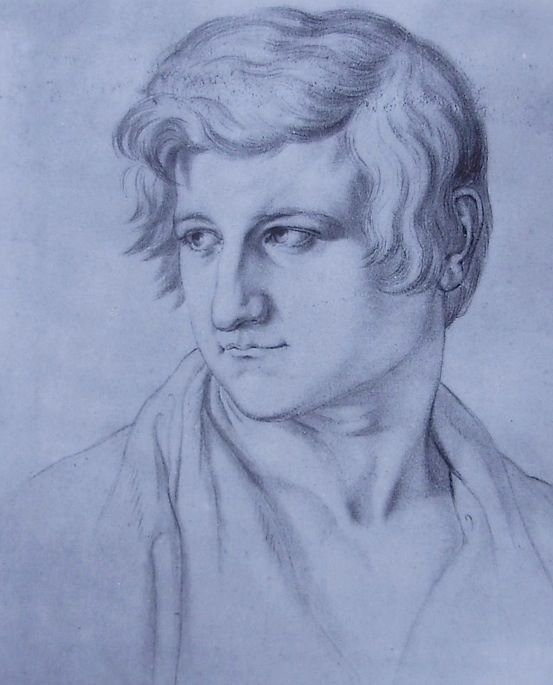

21-year-old Giovanni Morelli as seen

by Bonaventura Genelli in 1837

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 114)

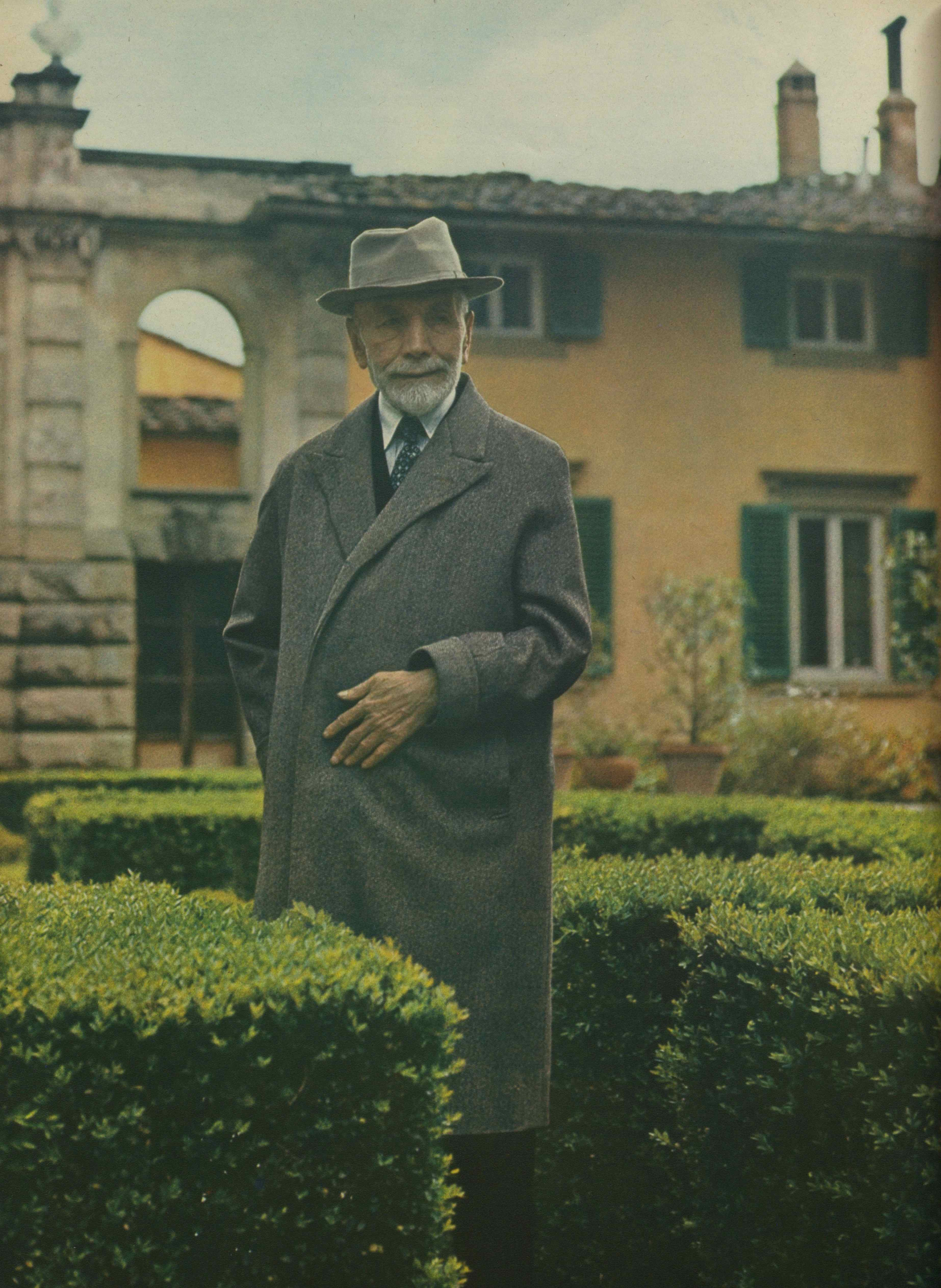

Bernard Berenson (1865-1959) in 1891 (picture: npg.org.uk)

Bernard and Mary Berenson (picture: itatti.harvard.edu)

(Source: Du. Schweizerische Monatsschrift No. 10

of October 1954/Theo Bandi)

(Picture: itatti.harvard.edu)

Giovanni Morelli as Seen Through the Eyes of Bernard and Mary Berenson

It has become a commonplace to speak of art connoisseur Bernard Berenson as of Giovanni Morelli’s actual ›heir‹ or ›pupil‹ (compare for example Zeri 1989, p. 6). This notion implies continuity. But a more in-depth image of the relations between the two foundational figures of the Golden Age of connoisseurship, we will only attain, if we also ask for discontinuities.

In February 1891, about a year after young Bernard Berenson had visited Giovanni Morelli for the very first time, he stated (to Mary Costelloe) that he could not really speak to him, Morelli wanting to be treated as a ›master‹ (McComb (ed.) 1964, p. 4).

Berenson, who at least on two occasions attempted to speak with Morelli in 1890 (or to impress him, one might also imagine), had actual opportunity to see Morelli ›in the flesh‹. The question, however, how Berenson, the younger Berenson, but also the elder Berenson, in fact ›saw‹ Morelli is not an easy, but rather a difficult question. Because this seeing of Morelli might have changed over the years; because Morelli was not someone that easily could be grasped, and because Berenson’s interests, from the beginning, might have been multi-layered.

In 1924, when Richard Offner meekly questioned publicly some of Berenson’s attributions (Secrest 1980, p. 335; Samuels 1987, p. 360f.), Berenson, in remaining silent, was not actually representing scientific connoisseurship. Because this Berenson who had publicly been challenged, could not allow his authority, his reputation to be challenged. And why? Because he simply lived on his reputation, on his authority. And it would have been too risky, putting his social position at risk, and because of this what he feared most, apparently, was disregard.

But as usual things are more complicated with Berenson, because in 1924, he did also represent scientific connoisseurship. In that he tried to show apprentice connoisseurs how a connoisseur could work: with his essay Nine Pictures in Search of an Attribution he did try to give an example of connoisseurial practices, to, idealistically, make connoisseurship interesting to young people, to the interested public, and to contribute to the general visual education of everyone.

In brief: in 1924 Bernard Berenson represented, one may say, various subcultures of connoisseurship at the very same time, a subculture of scientific connoisseurship, not averse to a culture of empirical verifiability, and a subculture of applied connoisseurship, meeting the demand of dealers, a subculture wherein scientific standards may have played a role or not – Berenson did not stick to the myth of the ›mere looking‹ by principle (this myth was rather, although paradoxically also challenged, perpetuated by Kenneth Clark (compare Clark 1960) –, but this subculture of connoisseurship, without any doubt, was averse to scientific standards in terms of empirical verifiability and transparence, and inclined to secrecy.

And the meeting of scientific standards of empirical verifiability would have meant that the general public, not only the scientific community, but the general public, would have had, at any time, the possibility to challenge Berenson’s claims, his views, his arguments. And this, for someone, whose social position was not a secured one as the social position of a professor at an university is a secured one, was simply impossible. Thus he remained silent, stopped answering letters by Offner, did not speak to Offner any more. And only after some years was to speak with him again.

One does not know if Berenson ever took seriously Morelli’s vision that art history should, in the future, turn to be a Kunstwissenschaft, based on scientific connoisseurship, because this would have meant that he would have had unfolded what Morelli only had envisioned: a scientific culture of connoisseurship, dedicated to the rigid study of form, but also complying to a logic of the good reason. And this meant that everyone was expected, at any given moment in time, to explain his or her reasons for or against an attribution.

Bernard Berenson (in close cooperation with Mary Berenson; compare for example Tucker 2014) left us, among other things, with lists (that, from a scientific standpoint, do only represent hypotheses, mere opinions or yet unfounded claims), and to such a culture of scientific connoisseurship Berenson did, with his lists, not or only indirectly contribute. What he inherited from Morelli was not this ambition of establishing and institutionalizing a new building of Kunstwissenschaft (his library and his legacy might be interpreted as his indirect offer to such an institutionalizing), but a powerful tool: the Morellian method (and all that it did achieve, or suggested of being able to achieve). A tool that helped him a great deal to establish as an authority (with his monograph on Lotto among other things), be it that Morellian tests in fact did play a major role in his connoisseurial practices or not (this might, by the way, differ as to the individual case).

Berenson, even prior to his monograph on Lotto (Berenson 1895), in about 1894 had written an essay on Morelli that he was going to publish only in 1902 under the title Rudiments of Connoisseurship (Samuels 1981, p. 371ff.; now in Berenson 1914-1920, vol. 2, pp. 111ff.). And this very essay can and also has to be put under scrutiny as to the question how Berenson did actually see Morelli: as the great inventor, who, unfortunately, or better: to Berenson’s luck, had chosen not to unfold his teachings, his method systematically, not to explore the field as a conquistador of connoisseurial positivism. And this, it seemed, was now up to Berenson. And what he did was to unfold the positivistic element in Morelli more or less systematically. And in doing so, probably unintentionally, Berenson helped to shape the impression (and the misunderstanding) that Morelli’s connoisseurial practices were nothing than the application of what Berenson chose (quite concisely) to call ›Morellian tests and controls‹.

Morelli seen throught the eyes of the author of the Rudiments of Connoisseurship lacked, suddenly, all of the other elements that were actually equally characteristic and important for Morelli/Lermolieff: the deep scepticism, the colorful eclecticism, and not the least: the sense of quality. This alleged Berensonian contribution to connoisseurship, the new weight that was given to psychological critique and to a sense of quality, however, was a questionable one, since Morelli’s books are not only scattered with illustrations of hands and ears; Morelli, in fact, used the argument of quality throughout (if often or mostly laconically). And it actually could not be claimed to be an innnovation to allegedly reintroduce the connoisseur’s sense of quality, and allegedly go on to work where Morelli allegedly had left off (but in fact one could do so, since, after having established this image of an extremly one-sided and merely positivistic Morelli). In fact: Morelli had simply taken for granted that Morellian tests were to be applied after a painting had been put under scrutiny intuitively. And this could mean to unfold everything imaginable, also psychological critique and also a speaking of artistic personality in a more general sense, although Morelli only on some occasions did so.

And Berenson did simplify Morelli also in that he aimed to show that, as to the rigid study of form, it was about a working with the stereotypical shape (compare Provo 2010, p. 63, note 198, with quotation from Berenson), which, as whe have stated in chapters one and two, is a simplification on the brink of misinterpretation, because Morelli aimed at a working with basic types, that have to be seen as a mental construction, derived from series of examples, and he did allow variance, not expecting a painter to repeat shapes mechanically and stereotypically (which can be demonstrated, for example, as to the case of Raphael).

But all this only requires further study, further discussion as to what rigid study of form is all about, and on how the working with formal analogies is also in need of empirical testing as to the validity of alleged analogies and alleged stylistic regularities (or even stereotypical shapes). And in this sense, again, Berenson, did not contribute to scientific connoisseurship, fostering rather the spreading of a one-dimensional image of Morelli, stripped of important features of his working practices and indirectly of his nature, and this to the benefit of, perhaps, unintentionally highlighting Berenson’s own contributions to connoisseurial methodology, which, if put under scrutiny, appear less original and innovative than they might have appeared in general and at his day. And this ironically again: while Berenson, as he repeatedly did, claimed to be a Morellian.

Finally: one cannot help to mention that Berenson probably knew rather little as to Morelli as a man, about his biography, his character, although he had had the chance to see him ›in the flesh‹. It may seem that Berenson’s image of Morelli, in that he suggested that scientific connoisseurship was a mere ›relief from politics‹ (as he had written in his Sketch for a Self-portrait), simplified also the complicated connoisseurial biography of Morelli. Who had seen connoisseurship also, earlier in his career and from about 1860 on, as something to keep solvent, and at the same time as something to help to protect the cultural heritage of Italy. But it was true, ironically, that at the time Berenson actually did meet Morelli in the flesh, the latter indeed was, i.e. had become a more or less disinterested scholar, beside of being a senator. Identifying with his intellectual project, and touchy as to young ambitious men wanting to impress him, but indeed only occasionally giving away (or selling) paintings anymore, and not relying, economically, on applied connoisseurship. And this, in brief, Berenson, might also have observed – and later recalled – perhaps not without envy. Because in his biography the Morellian method served as an aid to establish as an expert socially and economically, as an expert who could, in later years, only occasionally contribute to the subculture of actual scientific connoisseurship. Having to or wanting to make a living on applied connoisseurship. And with only occasionally and to some degree fostering the visual apprenticeship of young men like he once had been himself: at the time, when he first had met Morelli in the flesh. When being still and almost exclusively enthusiastic, mostly disinterested and willing to learn, to learn to see, and teaching others how to see. As he was again inclined to, when writing for example his Nine Pictures essay in 1924, wherein he does refer to connoisseurship as a kind of ›sport‹. As an intellectual and sensual practice that had to be practiced for its own sake, for the enjoyment, for the (precious side effect of) learning. And not for the merely utilitarian purpose. A purpose that, in the worst case, could result with having to remain silent if being challenged. Because speaking, teaching, debating would have meant to put his reputation and unsecured social position recklessly at risk.

(Picture: nybooks.com; jewishlives.org)

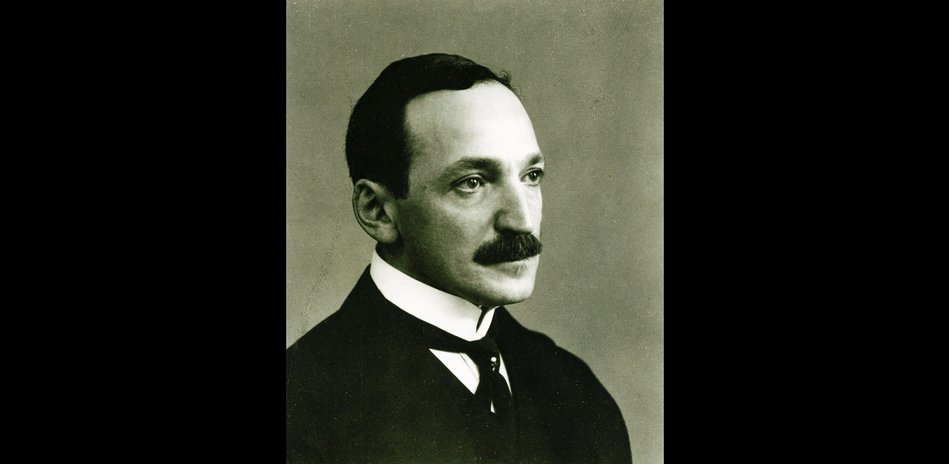

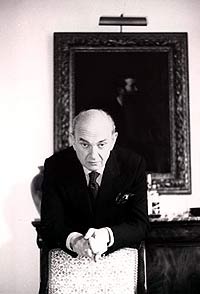

Max J. Friedländer (picture: smb.museum)

18-year-old Giovanni Morelli in 1834,

as seen by Wilhelm von Kaulbach

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 70)

Giovanni Morelli as Seen Through the Eyes of Max J. Friedländer (and Wilhelm von Bode)

Berlin-born connoisseur of art Max J. Friedländer (1867-1958) has become an authoritative voice, if it is about commenting upon (and also critically challenging) Morellian connoisseurial practices (see Friedländer [1992]; and compare for example Tummers 2011, p. 32f.). This is not unjustified, but at the same time it is necessary to become aware that at the time Friedländer was writing, yet confusion reigned as to what the Morellian method exactly was. And moreover, that Friedländer did not stand at all above this confusion, but, in struggling with various notions and perceptions of the Morellian method, was actually part of it.

Giovanni Morelli would have seen it with some wistfulness – that even as sensitive a man as Max J. Friendländer was entangled in two different interpretations of the Morellian method, although, in the end, one might also say that Friedländer, at least in a way, still got it right. But there was confusion, without any doubt, and it was widely reigning. If even someone as intelligent and cultured as Max J. Friedländer was somewhat confused. Could somebody in fact have managed to revolutionize art historical studies (as tradition sometimes has it), if, as to this someone’s methods, confusion does reign to a degree that even the most sensitive and intelligent ones remained confused? Because Friedländer’s interpretation of Morelli and of the Morellian method, made public in 1946 (re-edited in 1992), remained Friedländer’s primal and only publicly known statement. And it is the testimony of a mess. Of a mess, nevertheless, that easily can be entangled, but it is necessary to distinguish two different interpretations of the Morellian method, and it is also very useful to distinguish these differing interpretations. And thus this mess might also have something good. In that it is forcing one to entangle various interpretations of the Morellian method and its respective implications.

Had Morelli attained what he had attained (his attributions, his claims) by applying his method, or had he attained his results by intuition and had only, in retrospect, explained his results (won by intuition) by using his method. This was the question for Friedländer, and he tended to think, no, he was decided to think, that the latter was the case: of primal importance had been intuition, and the method that, as Friedländer knew, Morelli had designated (realistically, as he did agree with him) as a tool, had been of secondary importance. Only that this is, this understanding of Morelli is the expression of the classic misunderstanding of Morelli, a misunderstanding that Morelli, probably unintentionally but due to his being motivated to recommend his method eagerly, had also been fostering. But the method had been meant, and if Friedländer had also checked what, as to this matter, had been Morelli’s last word, to encompass both: intuition as well as an application of the Morellian tests and controls. There was no separating of these two sides of a coin, and exactly this had been Friedländer’s (and many others’) misunderstanding: that the Morellian method had been meant to replace intuition; that intuition, as a tool, was to be dismissed; and thus understood, the Morellian method, naturally, had appeared as a threat to all those whose primal tool was intuition, and who tended to think of intuition as the primal tool of the connoisseur, who, at best explained his intuitions after the fact, after having attained results, names, designations, intuitively (or did not explain at all; and to such a not-at-all-explaining the Morellian approach indeed was meant and still is a critique and a challenge, even if the Morellian method, understood in its narrow and specific sense, and aiming primarily at anatomical detail, is being dismisssed and replaced by another, possibly wider version of style criticism; what remained, still, in any, case, was the ambition of a scientific standard and of working routines that deserved to be called scientific).

But in fact there was no disagreement with Morelli at all, the disagreement was due to a simplified and narrowed interpretation of Morelli, which likened the work of the connoisseur to the (also simplified image of the) working of a botanist, who allegedly did only look up particular shapes in a book (containting all possible shapes, and containing also respective designations to such shapes). This widespread interpretation of Morelli did exist, no doubt, and Morelli knew of it, and one can blame him for having fostered a misunderstanding, or for not having done enough to put this right (he tried to do so. but, apparently, not loud enough; and, unfortunately, no pupil of his, no follower was capable or interested to do it for him, on the contrary, if we think back to Berenson); but to be fair, one would have to blame also some pupils of Morelli, and also Wilhelm Bode, the superior of Friedländer (and his predecessor as the director of the Berlin gallery), to have spread the word saying that Morelli, allegedly, wanted the connoisseur only to spot particular shapes and to dissect the canvas, in search of the distinctive shape, that one had to look up in an ›atlas of forms‹ (a tool, by the way, also imagined by Morelli, but never carried out, and not meant to be the expression of a narrowed methodological approach). Only that this all was a distorted picture of Morelli. But one, probably, and also due to the popularity of Friedländer and his rich connoisseurial wisdom, due to a little being known of other voices (for example of Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes; compare Ffoulkes 1911b, also as a counterpoint to Berenson) and due to the simplicity of the image – a simple checking of the earlobe –, one image to epitomize a simplified, and by simplification distorted image of Morelli, an image that, probably, will also persist (not least, one cannot help to say, because of Friedländer, despite his sensing what actually had been Morelli’s practices).

And if Friedländer still got it right, in describing how Morelli actually might have worked, relying on intuition, and attaining hypotheses thereby, hypotheses that were to be rationally controlled, tested, and possibly dismissed, Friedländer suggested that Morelli had also been dishonest. In that, allegedly, he had recommended something else than he had actually been practicing. But this image of Morelli, in an atmosphere of absolutist positivism, might also have created itself, and even without first-ranking connoisseurs articulating it. By itself and in spite of Morelli not at all wanting to represent such absolutism of scientific positivism, and in spite of his irony, that was not only meant to entertain or to cheer up, but also to relativize justly such absolutism of scientific rationalism, that, during the 19th century, and particularly in the second half of the century, seemed to be wanting to replace religion, in favor of a religion of science.

If Morelli would have been able to watch how the interpretation of his approach evolved, he would have seen it – we imagine – not with a smiling eye, but rather with disappointment, if not to say with horror, since, as dear was comical effect to him, and as much as he had liked to foster confusion occasionally (confusion resulting from comedies that he had enjoyed to stage himself), it certainly was not to the benefit of what he had seriously wanted, to have what he wanted being distorted to unknowability. And certainly, and maybe also fortunately, no scientific revolution in connoisseurship, understood as the absolutist reign of scientific positivism, resulted from all this, but neither did a more realistic and more subtle discussion of Morelli’s recommendations and his actual connoisseurial working practices.

Edgar Wind and Carlo Ginzburg

(picture: bodleian.ox.ac.uk; de.wikipedia.org)

Giovanni Morelli as Seen Through the Eyes of Edgar Wind and Carlo Ginzburg

In 1960, one year after Bernard Berenson had died, a new era as for Morellian connoisseurship was about to incept. Edgar Wind presented his subsequently influential Reith lecture(s) (later updated and published in Wind 1985); and the two daughters of Morelli’s apprentice Jean Paul Richter edited, partially, the correspondence between their father and Morelli (who also had been the godfather to Irma A. Richter).

Ellis Waterhouse, in reviewing this edition (Waterhouse 1961), gave expression to his sensing of being allowed to listen into the conversing of two gentleman. Which only can be interpreted as the result of heavy editing as for the full content of this letters. Because, for one, only about two fifths of the correspondence were published at all, and everything that had more directly to do with dealing was left out, as were censored the occasionally showing anti-Jewish resentments of both correspondents, and as was the all but gentle tone of many letters.

Nonetheless, a basis had been laid as for a getting to know better the nature of teaching of Morelli and the nature of the connoisseurial practices within the inner circle of Morellian connoisseurship. But another Italian connoisseur, Roberto Longhi, and also reading through this partially and partially heavily edited correspondence (Longhi 1985b), was inclined to ask, if Morelli had had any sense of quality at all (which might lead to the question, if actually Longhi had gotten to know Morelli at all, as a person, connoisseur, and particularly as a collector).

Edgar Wind, when lecturing, in 1960, on Morelli had not in mind to dig deep into the sources, nor was his lecture based on anything but a reading of the publicly available sources. And, as later Carlo Ginzburg, who based much of his subsequently famous essay Clues (Carlo Ginzburg 1979a; 1979b; 1988) (that also made Morelli famous) on Wind, the latter had meant his interpretation of Morelli to lead to a more general reflection: a reflection on a contemporary mentality of looking, as it were, that had its roots in the Morellian approach of allegedly being obsesssed with cherishing the authentic fragment; while Ginzburg, beginning in 1977, also did interpret Morelli as being representative for something over-individual, an intellectual paradigm, a style of (positivistic) thinking that was abbreviated in referring to a so-called »evidential paradigm«.

Ginzburg was sensing, already in 1977, that Morelli actually had been a character, eluding every all too simple picturing as a connoisseur and as a man; and Ginzburg, the brilliant historian, was all too aware, that a comprehensive Morelli monograph was actually lacking.

The presentation of the evidential paradigm, a much discussed concept in the humanities subsequently (compare Thouard (ed.) 2007), did, nevertheless, not result with many scholars digging deep into the extant archival sources, to gain a more in-depth image of Morelli. On the contrary. Much of the subsequent discussion remained on a rather theoretical level, while only few scholars – above all Jaynie Anderson – worked to make more source materials available (which is a process that as yet goes on).

Ginzburg, in the following, got also aware that he had, partly, misinterpreted Morelli (as had Wind), and since he had based much on his interpretation of Morelli on Wind (important as to a correcting of some misunderstandings/simplifications was Zerner 1978). And the author of Clues, according to more recent statements (see Agosti/Manca/Panzeri (eds.) 1993, vol. 2, p. 431; and see Carlo Ginzburg 2007, respectively Carlo Ginzburg 2009), apparently became also aware that the discussion had more or less excluded the debating of Morelli’s actual practices, and had focussed too much on theory.

All in all Ginzburg had made Morelli to some degree famous, in associating him with Sherlock Holmes, a figure of Western and of global imagination in its epitomizing the triumphs of reason, and with Sigmund Freud, another major figure of Western (and global) imagination (and specifically of the exploring of human psyche and imagination). But nonetheless Ginzburg had presented a rather one-sided interpretation, lacking the eclectic elements in Morelli’s practices. And lacking a more critical and in-depth questioning, if Morelli had actually lived up to his occasionally made explicit positivistic ideals (or to what degree he actually had lived up to these ideals).

And both Wind and Ginzburg had missed and left out something that had been part of Morelli’s nature: a deep, a strong scepticism that had fought, recurrently or actually all the time (and not being compatible with alleged triumphs of reason), inside Morelli’s nature or better: psyche, and had fought with his only occasionally confident (or even self-opinionated) positivism.

Not to mention his sense of fun, of (Socratic; romantic) irony (compare also Locatelli 2009, pp. 63ff.; and compare Uglow 2014), and his taste for practical jokes, for mimicry, and for various techniques of staging appearances, techniques that, actually, had rather little to do with with neither an »evidential paradigm« (Ginzburg), nor with a »cult of the fragment« (Wind), but all with the ambiguities of Morelli’s practices, with Morelli’s theatrical and often comedic inclinations, and, in a word, with his complicated nature and his complicated identity as a man that was, on the whole, as much inclined to self-expression as it was to secrecy.

**

TWO) MOUSE MUTANTS AND DISNEY CARTOONS

1937 Snow White trailer screenshot or:

Presentation of a stylistic paradigm

Inspired by Giovanni Morelli, whom he addresses once by his first name, Giovanni, Animator magazine author Barry Salt adressed the legendary Disney movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs of 1937 in the Winter 1987 edition of that magazine (see: Salt 1987). Stating that the Morellian method worked better, if applied to Twentieth century popular art (like animated movies), than it worked, if applied to the »high« art of the Renaissance, because Morelli, in Salt’s opinion, yet recognized, but still underestimated the problem of having enough reference material at one’s disposal, he assembles a sequence of observations of stylistic differences as to the rendering of the main character, Snow White, and also in the rendering of the squirrels, explaining these differences by the fact that various units of the studio were responsible for various sequences of that movie.

Snow White does indeed, as the title claims, »meet« Giovanni Morelli, who by 1987 and thanks to Carlo Ginzburg, was enjoying a certain popularity, even beyond the academia. Salt’s approach, in several aspects, emulates Morellian practice, but in our opinion isolates the empirical work from its theoretical framework, and in doing so ressembles rather a Berensonian application of the Morellian practice, if we understand by that the mere working with formal analogies on a mere empirical and formalistic level (not speaking here of the intuitive side of Berensonian and also Morellian practice), leaving any theoretical framework behind.

But the shifting from high art to popular art indeed is to be called illuminating, because it reminds us of Morelli’s theoretical presumptions about why formal regularities can be observed at all: Because it is the artist’s mind, wherin his inner notions of anatomy or landscape are, as it were, encapsulated, that expresses itself by, so to speak, externalising visual renderings of that inner notions. A contemporary of Morelli did probably understand Morelli correctly, if he did assume that the artist was doing this by nature, although Morelli himself, once under the influence of the philosopher Friedrich Schelling (Münz 1898, p. 91f.), whom he had read, met and translated as a young man, did prefer to leave it open, if artists did produce such signature properties, that helped to recognize them, in his opinion, not with an absolute, but with a higher level of certainty, more instinctively or more consciously (more crucial it was to see that the artists were allowed to do so not while realizing a stylistic paradigm as such – as the stylistic paradigm, given by the Disney studio as a framework for the individual artist to work with –, but only if – more relaxedly – realizing marginal parts of such very paradigms.

(Picture: derekwinnert.com)

In sum: What Salt points us to may be signature properties but these properties do rather belong to the class of properties Morelli called mannerisms or habits of the hand. He regarded these as potential clues or identifiers as well that could help to identify authorship (as connoisseurs since the 16th century had), and in this regard he did indeed point to the fact that of a great number of reference works were needed to work with these class of properties). But he regarded the mannerism as a different class of properties than the more classic Morellian properties, which were those that were to be seen as expressions of the artist’s mind and that were, more or less exclusively, the artist’s own. Not or very unlikely to be found within a different artist’s oeuvre, while, yet it remained still possible, that such properties could be copied (and attributions, in Morelli’s, opinion, were not to be based on the indicating to such properties alone).

We tend to think that the individual artist, contributing to the Snow White movie did not express his inner notions of anatomy, if he or she did render the main character Snow White, because a) this seems to be a central and not a marginal area within the stylistic paradigm, leaving room for mannerisms, but not leaving room for individual expression of artist’s minds, the reference being the studio’s model sheets. And b) because the shifting from anthropomorph characters like in Renaissance high art to anthropomorph animal anatomy like in the Disney world (less in Snow White, but in the Duck tales) requires a more conscious approach that again, leaves little room, for the natural expression, unless an artist had incoporated such thinking that it had become the core of his or her artistic activity itself, and thus an instinctive doing. Nonetheless, and despite the blurring of Morellian categories (which is ubiquitous, even within Morelli literature, not least because it is inherent to the contributions of Edgar Wind and Carlo Ginzburg), we would consider Salt’s feature as an original and illuminating contribution to the reception and interpretation of Morelli, that not least inspires us to recall the theoretical framework of the Italian connoisseur, even if the same applies to the theoretical framework as to the Morellian method as such: an orthodox, systematic and exhaustive discussion of this framework Morelli did, to the frustration of his pupils, never provide.

(Picture: novatale.com)

*

It is not without irony, a very welcome irony however, that another interpretation of the Morellian method has been provided by two Italian authors, one of which is to be associated with the European Mouse Mutant Archive. But their essay, published in the Journal of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology in 2012 (see Tocchini-Valentini/Tocchini-Valentini 2012), is not about Duck tales or Snow White – it is about the one Morellian classic, the one attribution that made Morelli, among other things, famous, and that is still being regarded as the one triumph of Morelli – although it is not always very clear why. It is about Giorgione’s Venus at Dresden. The one of Morelli’s finds that the two authors, Glauco P. and Marta A. Tocchini-Valentini, not hesitate to call »spectacular«.

The authors, in the beginning of their essay stay very close to Carlo Ginzburg’s famous Clues essay, that was, as far as Morelli was concerned, and as Carlo Ginzburg has become aware over the time, all too much relying on Edgar Wind’s Morelli radio lecture Critique of Connoisseurship. And we will see why.

As to the biographical informations on Morelli it bears repeating that yet Morelli did specialize in comparative anatomy at Munich – but the result of his studies was, that he gave natural sciences up altogether, aiming instead at a career as a writer, and especially as a playwright. And it is this passion for the theatre, that lead Morelli do other things than incessantly study art, is the one aspect of his biography that almost every writer on Morelli does fail to mention (because Morelli did, in later years, not like to recall this one passion he left behind and thus did not like to inform others about it).

The summary of Ginzburg’s essay that the authors provide suffers of the same shortcoming that already Wind’s lecture did suffer: if melts the two categories of properties that Morelli did distinguish into one (using the terminology of ›inconsciously‹ produced mannerisms, that Morelli found to be rather the less important category for both classes), and since we have spoken of the two categories above we don’t repeat ourselves. And more important: the authors step into a trap, that one would call classical, if it yet was a known trap:

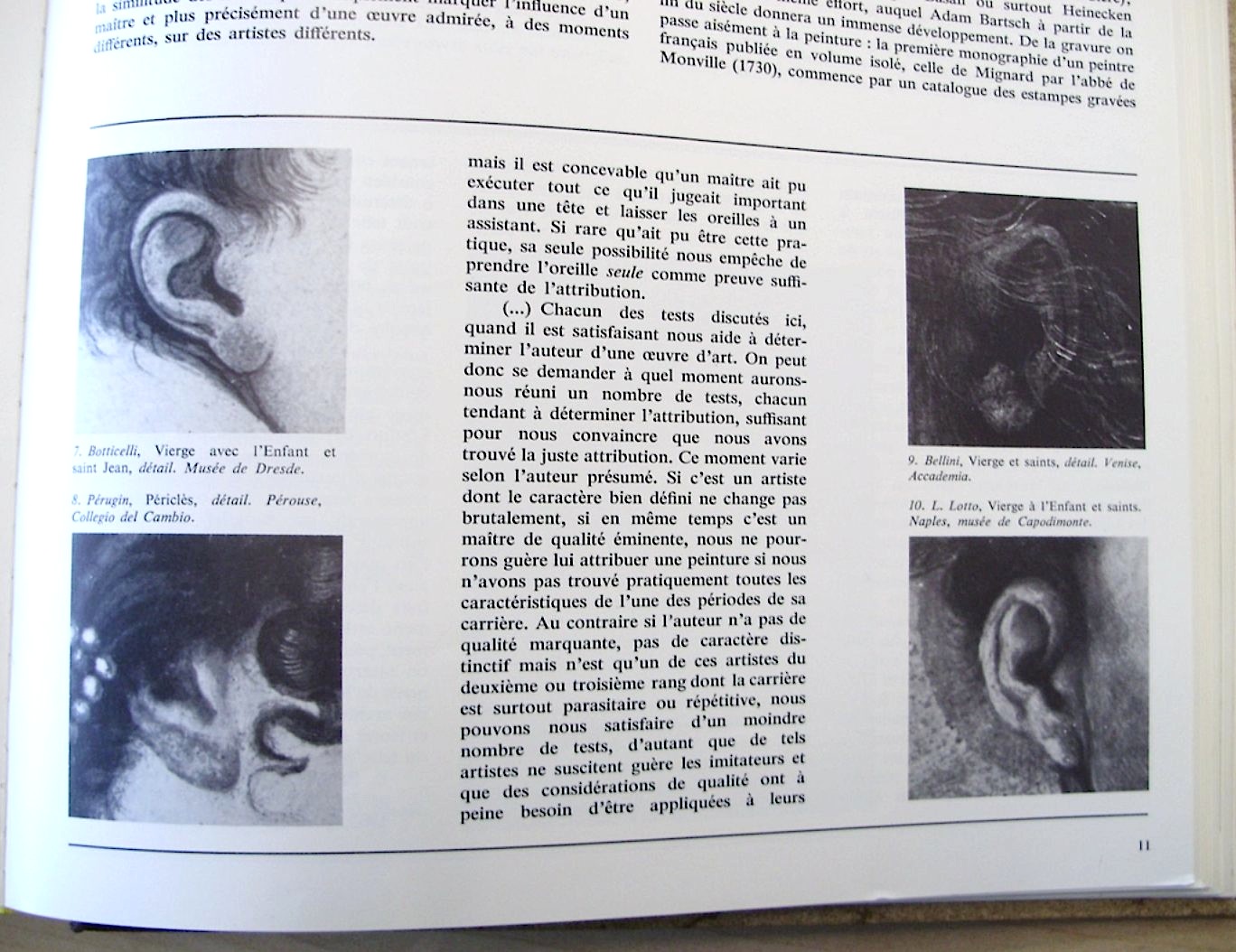

On this very page Morelli uses both notions: the notion of ›type‹ and the notion of ›basic form‹ (within the note) (picture: storiadellarte.com; Morelli 1890)

Although Morelli did represent shapes of hands and ears visually in his books – these shapes are not to be understood as stereotypical shapes that we are meant to find reproduced stereotypically in works of art by one and the same author. Morelli calls these shapes »basic forms« (Grundformen) and these shapes, rendered in his books represent the typical (as abstracted from many examples) in an even exaggeratedly typified form (»slightly caricatured« is what Morelli says himself). It is not about a matching or not-matching of shapes – it is about interpreting something (an actually found shape) as a realization of one particular type or not.

This is, paradoxically, not being of importance for the two authors discussing now the Dresden Venus. Because they simply seem to assume that a Giorgionesque shape of ear (the authors falsly think of a stereotype) does exist, and that a Giorgionesque hand does exist as well etc.

This is what most Morelli commentators (not all) do assume in discussing the Morellian method usually only on a theoretical level. Thus they fail to ask a simple question: how do these Giorgionesque properties actually do exactly look like?

Morelli himself names and even enlists various Giorgionesque properties in his books (compare our discussion of the subject here). He even names the ›pointy finger‹ as one. But how exactly does such a finger look like? And of what nature are the properties he names (no ear among them, by the way, although in unpublished notes Morelli seems to refer to, or to seek a Giorgionesque ear as well). In any case: no »basic form« nor actual example of the properties that he found to be the most important for the distinguishing of works by Giorgione from works by other authors, were actually discussed by Morelli in his books. And even more important, because it is about a »spectacular« find: his actual reasons for his seeming certainty to attribute the Dresden Venus to Giorgione were given publicly. Upon which properties did he test the picture? It simply rests unknown and is open to speculations, be them based on what Morelli actually says and alludes to or not.

This all does now not mean, in our opinion, that the two authors discussed here work on completely inadequate premises: No, they did understand the principle of the Morellian method well, but they did misunderstand the nature of the properties Morelli used to work with and simply give, like many others before, Morelli much credit, although he failed in giving transparent justifications for his attributions that meet only most basic of scientific standards and expectations of any scientific community (and one might add: it is not our duty to deliver what he failed to give and maybe only kept to himself).

What is original in the authors discussion of Morelli, something they actually add to the method in interpreting it, is the suggestion to formalize it in terms of relative probabilities, referring to Baysian principles. And we finish the discussion of our second example of a modern interpretation of Morelli with saying that, in our opinion, a more formalized procedure is one way to think Morellian principles further. But it seems to bear the risk of formalizing something that is of a different, and less stable and regular nature than the authors seem to assume. And the speaking of visual properties in terms of Baysian principles runs at the risk of another suggestion: That the interpretation of visual detail is as scientifically progressed as the formalization is.

It is definitively not. Because the Morellian method, if it is assumed that it is about the having an eye for and to memorize stereotypes, is simply misunderstood due to simplification. This is what its propagators occasionally did suggest. In withholding the fact (or due to their own misunderstanding of Morelli) that Morelli himself did not think Morellian properties as to be stable like a fingerprint. It is about a level of stability rather, and again, of that of signatures. And as we all know our signatures might be rendered in stereotyped shapes – but try to match the stereotype with an actual signature and you know what I, in this section, was talking about. And another way of checking my interpretation of Morelli, given here, is the comparing of the examples that Morelli refers to as representing examples for one and the same type. In brief: whoever does visualize what Morelli is talking about may check our here talking about it.

**

THREE) GIOVANNI MORELLI SEEN THROUGH THE EYES OF… (II)

In 1978 the Revue de l’Art – in numéro 42 – came back to Morelli

(Picture: beazley.ox.ac.uk)

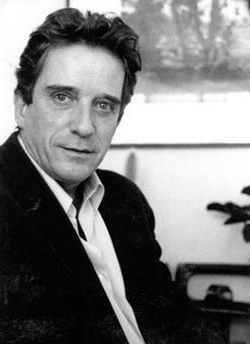

In his 1984 TV film Wer war Edgar Allan?

the Austrian director Michael Haneke had,

in a sequence, an art student wandering around at the university

looking for the lectures on Morelli

(compare Grundmann (ed.) 2010, p. 292)

(picture: tvspielfilm.de)

Morelli who had mused, in 1861 and on his journey with Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, about a ›certain Raphaelesque something‹ in the painted rendering of fingernails (compare Anderson 2000, p. 52; Morelli 1890, p. 45), certainly knew about the comical effect of being obsessed with such detail.

In other words: since he was inclined to comedic appearances, he could actually live with such effect.

If however, he could have lived with a Morelli caricature asserting that he did recognize painters solely ›by the earlobe‹, is another question. Because distorting simplification beared on an intellectual project he was keenly dedicated to and reduced this project to something ridiculous. Thus: he did, repeatedly, contradict the mentioned assertion which is nothing but a terrible simplification, even in the mouth of well-known and respected art historians.

A more specific and more recent context of a coming back to Morelli:

discussing the form of Giovanni Bellini’s signature

(see Hegener (ed.) 2013, pp. 232ff. (Debra Pincus),

and specifically pp. 236ff.).

Still: the Morelli caricature is part of his fortunate-unfortunate fortuna critica. But if Morelli was belittled and also more and more ignored, the here unfolded intellectual panorama of his aftermath one may rightly call impressive: he did indeed inspire other thinkers, other connoisseurs, art historians, archeologists, historians, cultural historians and writers. And if he had managed this by solely being obsessed with ears, hands and fingernails – blessed may be these nails.

In fact: it probably had been also due to his inclination to wayward appearances that he has become – deservedly – an embodiment of close observation, although close observation had existed in other ages as well, and if Morelli does indeed and rightly so represent a positivistic, in its ambition (and not necessarily in its real appearance) positivistic version of close observation and style criticism, one should not forget that he was and remained a sceptic. In a word: such contradictions made one think as well, and any historian dealing with Morelli has to work his or her way across these contradictions.

Another more specific context

of a recent coming back to Morelli:

as regards technical practices used by Leonardo da Vinci,

Morelli’s opinions on black bone under modelling

have been, in 2011 and 2012, considered as being

still relevant (Anderson 2014, p. 10 and p. 12, note 10;

the context being also a discussion of the painting known as

the Salvator Mundi, that only recently has been attributed

to Leonardo); Morelli’s letter of 1880 had dealt with

the Paris version of the Virgin of the Rocks,

and less known, in this context, seems to be the fact

that Morelli considered the London version as not being

an original by hand of Leonardo;

see: GM to Jean Paul Richter, 14 July 1883.

We have addressed the question how other connoisseurs, first-ranking connoisseurs did see Morelli. We have addressed the Morelli interpretation of those writers who did much to secure him a renewed fortuna critica. And we have discussed two examples of style criticism, inspired by and referring explicitly to Morelli.

In our final section we come to discuss the question of how Morelli was seen by two renowned French art historians (and thus: in France), and we close this chapter with two philosophers taking a look at the Morellian method, not without mentioning that now also the Morelli interpretation of art historian Erwin Panofsky (contained in a only recently published letter) can be studied and questioned, and that the question of how Sigmund Freud did see Morelli has been dealt with in Cabinet II and Cabinet V.

Hubert Damisch and Daniel Arasse (1944-2003)

(picture: artforum.com; typotext.hu)

Heinrich Wölfflin (1864-1945)

Giovanni Morelli as Seen Through the Eyes of Hubert Damisch and Daniel Arasse

If one was to think of Giovanni Morelli as the author of a picaresque novel, and of his alter ego Ivan Lermolieff as the hero of that picaresque novel, crossing the boundaries of nationalities and intellectual milieus and ambiences, one would also have to dedicate a special chapter to Lermolieff in France. To Lermolieff entering France, entering Parisian ambiances, and the milieu of the avantgarde journal Tel Quel very in particular. Lermolieff, in fact, that picaresque hero, born from the head of Morelli, entered that milieu too (as he already had entered various others, for example that of psychoanalysis), when French art historian Hubert Damisch, in the early 1970s, not only discussed the relation Morelli-Freud (as Jack Spector had in 1969 (Spector 1969), and some years later Carlo Ginzburg was to discuss it again), but also a special relation that Damisch, in some sense, did rediscover (Damisch 1970; compare also Cohn (ed.) 2003). And this was the relation between Morelli and Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin, a relation, that in some sense had to be rediscovered, since, after Morelli had died, connoisseurship and Kunstwissenschaft had pursued more and more separate ways, and also, and certainly more than Morelli had wanted, had developed separate cultures and lived biographies rather of stepsiblings, of half relatives, and had not seen themselves as being as tight a family as the vision of a Kunstwissenschaft based on scientific connoisseurship had implied and also fancied this relation to be.

Lermolieff entering France had to overcome various problems of terminology and language, but in the early 1970s found himself among intellectuals discussing the structural dimension of language (as the language-like structure of the human subconscience); and if Morelli had lived to see the future career of his’s and his alter ego Lermolieff’s career this far, he would have noticed that as narrow his intellectual approach might have seemed to some, as inspiring it also seemed to others, more inclined to think on an abstract level, to think also, very in particular, about the detail and the whole in abstract terms, with the notion of the whole now acquiring seemingly a new meaning, if Damisch, with Wölfflin, was now referring with it to the formal evolution of art history and in art history, and not only to the whole of the single art work that had to be placed into the whole of history; by using the means of applied connoisseurship, the practice that had ever seemed to be a very narrow-minded, merely instrumental practice to some (not being homme de lettres).

But actually this meaning was not new at all, and Morelli had always implied to think of art history, in analogy to natural history, as an evolution of styles, individual styles, but also ›family‹ styles, schools, regional cultures, national cultures (made of regional cultures). And if it had seemed that Wölfflin had turned away from Morelli (with whom he had exchanged letters; see M/R, p. 578; Wölfflin 1893; Goldhammer Hart 1983, p. 237ff.; Kultermann 1991, pp. 37ff., p. 47; and compare also Frommel et al. (eds.) 2012), Wölfflin, in his turning to the overindividual dimension of stylistic evolution and his naming of overindividual categories of style, had only explored the one extreme that Morelli, in his vision of art history, had implied (while the other extreme had been the determination of authorship of the single object in question). And it was only naturally to think of these two art historians as belonging to one and the same family. Morelli might have represented connoiseurship, but his actual ambition had been to rebuilt art history in terms of a Kunstwissenschaft. And the latter term was also the term that Wölfflin had used, a Kunstwissenschaft ›without proper names‹, which might have seemed as a dismissing of the problem of discerning individual styles, but actually no history of art, in fact, could ever be thought of without objects, representing (if not names) particular moments in space and time.

Daniel Arasse, on his part, and another French art historian, had early in his career even identified with Morelli to the degree that he had developed the vision of writing crime fiction screenplays with a detective named Jean Morelli (Maak 2003); but in the following had turned away, but again seemingly, from him. In that the chose the thinking about the detail as a major issue (Arasse 2008), in that he chose to write essays on works of art and motifs also associated with Morelli (see Arasse 2002; the motifs of the Titian/Giorgione Venus, the Magdalen), in that he dealt with the problem of attribution more from the intellectual dimension of the art work (thinking intellectual decisions, manifesting in works of art as a clue), and in that he stressed the significance of the detail not only in terms of a clue, but also in terms of something potentially subversive to an (ideologically defined) vision of the whole. The detail, thus, represented the cheeky objection against any master narrative having lost its sense for the marginal, repressed and falsely neglected. And with this Arasse, to some degree and in spite of his seeming turning away from him, again ressembled Morelli, who once had instrumentalized the detail, in some sense, to mobilize subversive potential and energies, to be used against the master narrative of his favourite sibling antagonists, namely Joseph Archer Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, who on their part had represented other interests and other ways to think the history of art to be written, but missed, one cannot help to say it, the flights of the mind of Lermolieff, who, born from the head of Morelli, still today is on his way to cross many a border, and to ever enter many a new intellectual territory in the future.

(Picture: amazon.fr)

68-year-old Giovanni Morelli as seen

by Crown Princess Victoria in 1884

Richard Wollheim (1923-2003)

(picture: berkeley.edu.com)

Giovanni Morelli as Seen Through the Eyes of Richard Wollheim (and John H. Brown)

Theorists have looked at the Morellian method from the point of view of theorists. And generally theorists looking at the Morellian method have found rather little to be worried of. But theorists, namely, philosopher Richard Wollheim (Wollheim 1974), showed also rather being worried about what practitioners seemed to have rather neglected over the course of years.

But what practicioners? Who would there be to blame, if there seemed to have been so little empirical testing of the Morellian method (see Wollheim 1974, p. 190)? And who would there be that one could ask how the illustrations from Morelli’s books actually were to be read (p. 192)? And we are confronted with the paradox, that actually philosophers, theorists, seemed to have a far better understanding of the Morellian way of thinking, its strengths, but also its shortcomings, than other connoisseurs might have had. Not to speak of the art historical tradition that neither had shown inclined to empirically test the method at all, nor to clarify confusions that up to the present day do simply prevail.

A paradox that also could be turned into a severe critique of art historical tradition, but the philosophers, Richard Wollheim and, in more recent times, John H. Brown (John H. Brown 2008), remained rather mild in their critical judgment, but still made clear that, in their view, there was little to say against the Morellian method from the point of view of a philosopher, but that comment on the Morellian method had still been rather poor.

And in the eagerly being dedicated with the Morellian method, there was something else that, indirectly, did show: the Morellian way of thinking with its latent analogy to natural history, with its unspoken systematic ambition (unspoken probably due to Morelli’s knowing that he could not be a systematist) appeals rather to scholars being receptive to theoretical thinking and also to a debating of theoretical and methodological questions. If this is lacking, no interest to test, to question, to comment upon, not to speak of a further developing of an approach will ever be the result, all the more, if a basic interest to implement scientific connoisseurship (or scientific standards in connoisseurship) is lacking.

It is a pity that such keen interest seems to be represented by theorists, who obviously do better understand the theory and do better see the practical implications of a theory than practitioners, but in the end, also lack the practical experiences in working with the Morellian recommendations and routines. Which would have, if it were differently and as we imagine, also have resulted in being a little less favourable in judging the Morellian method that not only might ever have looked convincing from the point of view of theorists, but also might have looked fuzzy from the point of view of many practitioners, who also might have had their point, but did not speak up to tell of their experiences, as at least two philosophers, two theorists, as clear-sighted as Richard Wollheim and John H. Brown, did do, telling of their experiences while trying to think and rethink the Morellian method.

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH PART II:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet I: Introduction

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet II: Questions and Answers

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet III: Expertises by Morelli

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet IV: Mouse Mutants and Disney Cartoons

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet V: Digital Lermolieff

Or Go To:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | HOME

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Spending a September with Morelli at Lake Como

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | A Biographical Sketch

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Visual Apprenticeship: The Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Connoisseurial Practices: The Giovanni Morelli Study

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | The Giovanni Morelli Bibliography Raisonné

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | General Bibliography

68-year-old Giovanni Morelli as seen

by Crown Princess Victoria in 1884 (detail)

Cabinet IV: Mouse Mutants and Disney Cartoons

We discuss various representations of Morelli here in this chapter. Knowing that from early on Morelli had known something of representing people. Because during his studenthood not a few Munich artists had actually made portraits of him (used also throughout this monograph).

Some of which had become his friends (like Mende and Genelli); while at least Wilhelm von Kaulbach, who had also represented him, was later not much liked by him (and we don’t know if this also does apply to Kaulbach’s portrait of Morelli).

While we thus may assume that Morelli must have had at least an intuitive and physical feel of how artists imposed their habits of the hand and mind upon the image he yet had of himself, we may also assume that this is one experience – being the sitter to a portrait –, among many other experiences to which the originating of his connoisseurial thinking might traced back to. And we may say that he did never stop to think about how and why artists left their individual imprint as artists upon representational form in art.

But we know also that Morelli did like to play with representations of himself, that is with outer appearence, and we have to stay aware that Morelli might not have liked static representations of him. But rather causing a little confusion here and there. By making for example people believe that he had been a sitter to Genelli’s representation of Prometheus, which is probably not true, but just an invention.

And thus we have to remain critical as to any representation of Morelli (or alleged representation), and stay in the habit to critically compare the most diverse representations of him. Which is what we do here, focussing in particular on representations of his method.

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship I

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Interlude I

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship II

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Interlude II

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship III

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet I: Introduction

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet II: Questions and Answers

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet III: Expertises by Morelli

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet IV: Mouse Mutants and Disney Cartoons

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet V: Digital Lermolieff

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS