M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

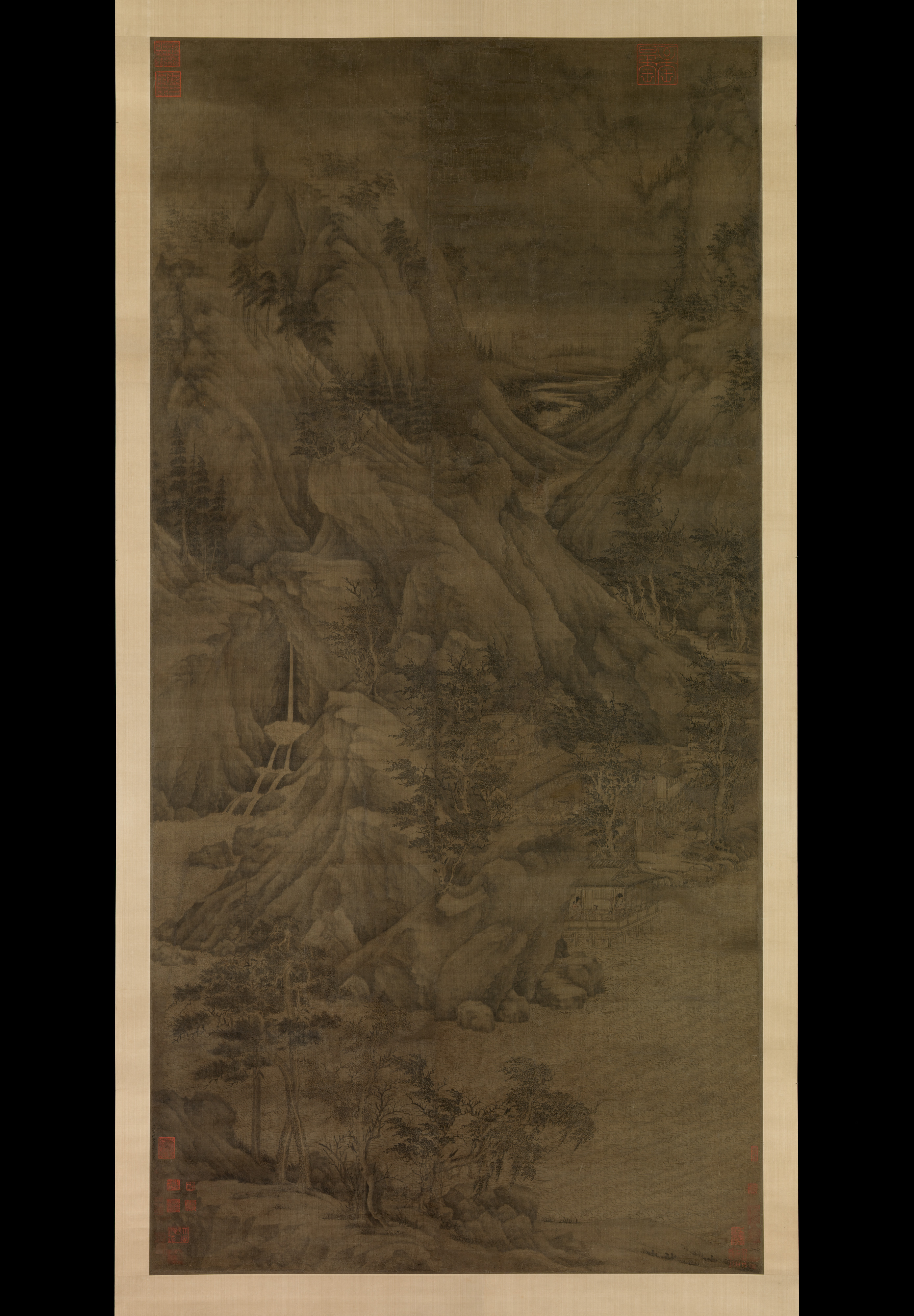

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

James Cahill vs. Zhang Daqian

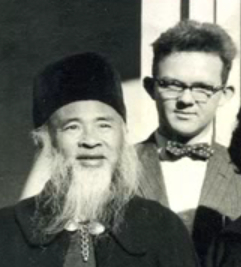

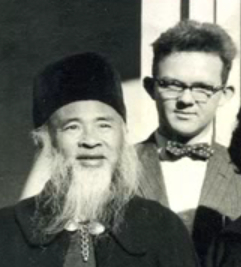

(Picture: arthistory.berkeley.edu)

(3.-6.11.2022) James Cahill (1926-2014), seminal figure in the history of Chinese art history met Zhang Daqian (1899-1983), seminal figure in the history of Chinese painting, connoisseurship and forgery, for the first time in Kyoto in 1955. In Japan, where Cahill did spend some time as a Fulbright student, he even consulted Zhang before buying a Chinese handscroll for himself (»Chang [Zhang] pronounced it genuine, and I bought it.«). After leaving Japan late in 1955, Cahill went on to work, in the spring of 1956, for Osvald Sirén in Sweden, before travelling extensively in Europe and then returning home to the US, where he was to start working at the Freer Gallery at Washington, D.C, in 1957.

It was during these very years – 1955-1957 – that Cahill was beginning to realize that the role of Zhang Daqian, within the history of Chinese painting, connoisseurship and forgery, was rather ambiguous (to put it mildly). And it was during these years that something was taking shape that I would like to describe as an antagonism (one could also try to describe it as something else, and we will see how we will describe it in the end). In Cahill’s words: »The project of following Chang Ta-ch’ien's [Zhang Daqian’s] tracks and trying to detect his fabrications became a fascination for me; it was like playing a complicated game with a very capable adversary.« And this game went on even after Zhang Daqian had died in 1983, and till the end of James Cahill’s life.

I have chosen to look more closely into the relationship of these two men – focussing on the years 1955-1957 – because, for a number of reasons it seems worth to do so: because the history of connoisseurship is not only a history of European connoisseurship (of European art), and it seems very reasonable not to neglect, in fact to include the history of Chinese connoisseurship into this history. But also to raise a number of questions (this page, in fact is assembling materials, so that certain questions can, perhaps, be asked more precisely, and I do not claim at all, that all of these questions could be answered at all, or very easily). What questions are these? For example, what kind of Western connoisseurship was it, represented by Cahill, that encountered Chinese connoisseurship, represented by Zhang Daqian (if, in fact, he represented such)? What was the state of things in Western connoisseurship, when James Cahill took on this challenge, on the basis of Western, but not only Western expertise, to detect forgeries by Zhang? From what point of view, certain ›forgeries‹ are to be seen as forgeries at all, and what about Chinese standards of perceiving deception, authenticity and truth? (Is there only one standard, as is often implied, or does, as in Western connoisseurship, a number of very diverse traditions exist?)

What I am starting here, is meant as a kind of experiment. I’d like to find out, if it seems possible to expand my horizon and to enlarge my view as to the history of connoisseurship. And it seems like a good choice to me to start with studying in more detail the relation of one notable American professor of Chinese art history with one legendary (exiled) Chinese painter, connoisseur and forger.

(Picture: author unknown;

detail from a 1958 picture James Cahill showed

in one of his lectures that are available on Youtube;

according to Cahill the picture was taken on occasion

of a visit of Zhang Daqian at the Freer Gallery in 1958)

Whoever reads through the numerous reminiscences written by James Cahill, or listens to his

lectures, will notice that his judgment on Osvald Sirén is rather harsh and fairly negative.

Sirén represented an old school in scholarship, with which Cahill no longer felt at ease.

And the problem posed by Zhang Daqian and his ›fabrications‹, Cahill was encountering just

at the time he was embarking on developing his own understanding of attributional studies

in the framework of Chinese art history.

Zhang Daqian was becoming a sort of friend for Cahill (he called him a friend, when blogging,

in 2012, on ›Old Mr Zhang‹, but also a ›ghost haunting him‹), and this ambivalence

has to be taken into account from the beginning. Zhang was becoming a friend, but the

professional identity as a professor that Cahill was to build, was built on a more rigid

approach towards attributional problems, than the (Berensonian) approach practiced by Osvald

Sirén did represent.

A clash did perhaps not really happen, but the ›game‹ than enfolded – one might think also of a dance –

was due to an antagonism that Cahill could not avoid. His professional identity as a professor (in Berkeley,

beginning in 1965) demanded that Zhang Daqian could not ›get through‹ with what he did. And this

explains why Cahill, till the end of his life felt haunted by Zhang Daqian, and why he awoke,

one Sunday in 2012, thinking of his old late friend, Mr Zhang, and also felt the need to blog on him.

Anyone interested in the history of connoisseurship has to note that James Cahill embarked on an endeavor

at a time connoisseurship was becoming really unpopular in Western circles of art historians, especially

the Berensonian approach (but usually no other approach was known). I have, in a different context,

spoken of the years around 1960 as a ›watershed‹. Berenson had died in 1959, and from the viewpoint

of someone seeking for a more rigid approach in attributional studies, Berenson’s legacy was simply

a desaster. There was not much, in terms of methodology to build on. Western art history had failed

to establish a truly scientific culture of connoisseurship. Connoisseurship had become and was something

else, and nobody, at around 1960, was interested to go back to beginnings, which would have meant to

go back to Giovanni Morelli, and to think about what scientific connoisseurship actually had meant and

had wanted to be. And what it could mean in the future. In the framework of Chinese art history things

were a little different: if Sirén was outdated, there was also not much attributional studies could be build

on, the field had to be discovered anew, or in other words: the field was open. But while art historians

of Western art tended to discard connoisseurship without feeling the need of finding a replacement, since

a fundamental order of things seemed to exist, James Cahill obviously did not feel at ease with the state

of things. This does not say that Cahill was necessarily a ›born connoisseur‹, but, as a young scholar,

we was in the position to do something in the field that had opened to him.

If one does look at how James Cahill embarked on identifying ›fabrications‹ by Zhang Daqian, and if one compares

his approach with the Cahill in 1999, arguing in the notorious Riverbank controversy, it does clearly appear

that the connoisseurial approach of James Cahill never turned to be a very systematic one, based on clear

premises and methodological rules. He was drawing from experiences made in the past by other connoisseurs, Eastern

as well as Western, but never developed a very systematic approach, but rather an improvised one, that could also

develop rather in an ad-hoc manner (typical are the many ›postscripts‹, which means also: new lectures, new lists,

new arguments found. The matter was actually never finished. And what Cahill never embarked on, is represented in a more

recent German dissertation (on Dong Yuan): the more systematic study of the types of arguments used by connoisseurs

in (for example) attributional studies dedicated to Dong Yuan over times (see Christian Unverzagt, Der lange Schatten

des Ursprungs, PhD-dissertation, University of Heidelberg, 2005).

This might be a path into the future; but the beginnings of James Cahill, of getting to know about Zhang Daqian, forger,

at all, are also interesting. Due to the nature of the reminiscences of James Cahill (rather unsystematic as well, so

that the informations are rather scattered), it is not quite clear how exactly this happened. But it seems that Cahill

heard stories about Zhang Daqian’s ›fame‹ as a forger for the first time when looking at pictures in Hong Kong. And it

seems significant that this was a story about ›fame‹ rather, than about criminality.

Cahill described his stance towards Zhang Daqian as a forger once as ›non-judgemental‹. But he was well aware of the moral

questions that at least surrounded and are surrounding the activity of a forger (and also Zhang himself was obviously

aware of these questions, because otherwise he would not have carefully avoided to go too far in what he did). Cahill

in some way just ›suspended‹ to raise such questions and seemed to handle the matter in a sporty manner (which may be

the right strategy, if one wants to remain a friend to a forger). But he did express also Schadenfreude, when on

the one hand admitting that he himself had been taken in by Zhang, and on the other hand describing how the British

Museum had been taken in. And it is just one step from informal norms that actually would forbid Schadenfreude, to actual

rules and laws that would forbid art forgery. On forgers, diverse resentments can be projected (Anti-British, certainly

also Anti-Western) and it is only too obvious that the popularity of Zhang Daqian has also to do with such resentments

(people who have such can easily identify with him). Cahill seems to have identified to some degree with Zhang (and also

admired him to some degree), but strived to keep out moral (or legal) aspects from the matter. And a similar ambiguity

seems to come in sight when Cahill addressed Zhang’s ability as an artist, belittleling him to some degree on one

occasion, but speaking of him as a giant on others. Brief: it may not have been that easy to come to terms with an

adversary such as Zhang Daqian.

James Cahill in 1955-1957 (and beyond)

1955

James Cahill spends a year as a Fulbright student in Japan, where he meets Zhang Daqian for the first time. The Fulbright year is prolonged for a couple of months. Osvald Sirén, who also stays at Japan, is inviting Cahill to work with him in the next spring as an assistant. Via Hong Kong Cahill travels to Rome (at the end of the year or early in 1956).

1956

In the winter/spring Cahill works for Sirén near Stockholm, helping with lists of works of art by Chinese painters (a brief reminiscence is dedicated to Working for Sirén; after than he extensively travels in Europe, before returning to the US (a sketchy reminiscence is dedicated to that year of rather restless travelling ›from Stockholm to D.C.‹). In Germany he meets Victoria Contag.

1957

Cahill has returned to the US to finish his dissertation and to become a curator at Freer Gallery, Washington D.C.

(Picture: Thiago Santos)

Cahill: »Chang [Zhang] visited the Freer on several occasions during these years, to see paintings and talk; […]. I learned a lot from going through parts of the old Freer collection with Chang, showing him paintings I had discovered among the neglected ones, asking and recording his opinions on these and others, and listening always for clues to his practice of making forgeries. I remember once asking him over dinner (at the Peking Restaurant, out Wisconsin Avenue) about the several versions of Chang Feng’s portrayal of Chu-ko [Zhuge] Liang: one in Japan (published in Yonezawa’s book on Ming painting) and another in the hands of a New York dealer – both paintings for which I knew Chang had been the source; and a third, which I took to be the original, published in the volume of Ho Kuan-wu’s collection, T’ien-ch’i shu-wu ts’ang-hua chi. Which, I asked him, was the genuine work? But Chang was not to be cornered: his answer was that Chang Feng was quite fond of that subject, and painted it several times. They were all genuine. Foiled again.«

Cahill: »Another of Zhang’s Dunhuang forgeries was offered to the Freer Gallery of Art while I was curator there, in 1957 or ’58, and fared less well under examination: the yellow pigment proved to be a chemical compound not used until the 19th century, and our then-scroll mounter Takashi Sugiura immediately pronounced the silk to be modern Japanese. Technical examination of paintings can sometimes supply negative evidence; it can virtually never prove authenticity.«

1991: Chang Ta-ch’ien’s Forgeries of Old Master Paintings

2001: Chinese Art and Authenticity

2008: Chang Ta’chien’s Forgeries

2012: All About Old Mr Zhang

»I may have related already, but let me do it again, my regrets over having turned down his [Zhang’s] request, delivered to me by Zhang’s son, that I write another essay for an exhibition of his paintings – I had done one, which he liked and often reprinted, for a 1963 show of them in New York, I think it was at the Hirschl & Adler Gallery. This second request came after he had moved to California and was living at Pebble Beach near Carmel, and had begun painting in a new style in which he splashed ink and color onto the paper as if (but not really) randomly and then added some fine drawing – a few houses, perhaps – to pull it all together into a landscape. Why did I decline? Because I knew that this new style, hailed by some as Zhang’s brilliant response to Abstract Expressionism, was in considerable part adopted because his eyesight was failing – he had diabetes – and he wanted to minimize the need for detailed drawing in his paintings. Splashing was easier. And I didn’t see how I could write about his new style without revealing this truth about it, as I didn’t want to do.«

How does one write on Zhang Daqian as a historian? All that self-fashioning, all that self-mystification,

and all these uncritical narratives in the wake of all that self-fashioning. Does a multi-faceted personality

like Zhang Daqian really deserve this amount of rubbish?

Writing as a historian, I am becoming aware, that I am running into the danger to become a spoilsport.

But this is interesting, because this is exactly the position James Cahill was in, when finding out about

some of the games Zhang Daqian played. And James Cahill had no other choice than to become a spoilsport,

and he somehow did manage, still to perceive Zhang Daqian as a friend and not to harm him (by insistingly

working against the forger Zhang Daqian). But it seems that all the noise about Zhang Daqian as a forger just

made him more interesting anyway.

If I choose to write on Zhang Daqian as a historian, this does not mean not to appreciate some of these

games Zhang played – as games –, this is simply a different level. But to say that – and to enjoy some of

these games – requires to have developed an understanding of how some of these games worked. And this seems

not to be that easy.

I choose to be a spoilsport for the moment. Because some of the rubbish, concerning the encounter of Zhang Daqian

with Picasso, has to be contradicted. This is the historian speaking. And here are some corrections:

No, Zhang Daqian did not meet Picasso in Nice (or in Paris), and not in 1950. The two men met in villa

La Californie at Cannes – in 1956. And about how exactly this took place I am going to say much more

in my book dedicated to the matter.

And no, Picasso had not seen works of Zhang Daqian in Paris in 1956. In 1956 Picasso never left his Cannes home,

except when attending some bullfights in the South of France.

And no, the press did not take notice of that encounter at all, nor was it labelled an encounter of two champions

representing East and West (if fact the meeting got totally ignored, which was different, when, in 1961, Zhang

met with painter André Masson; this meeting got some attention).

And no, Picasso was hardly inspired by Chinese ink painting. I am also going to say more on that matter in my book,

but for the moment I can say that Picasso produced ink paintings in the July of 1956, and he seems to have realized

himself that these looked somewhat similar to Chinese ink paintings, and it is true that he had been given a

Qi Baishi album by a Chinese cultural delegation – that had visited him weeks before Zhang Daqian did –,

but it is very easy to find similar ink drawings by Picasso – done in the same style – in earlier periods.

And the visit by Zhang did not stimulate a Chinese ink painting frenzy in Picasso. If we trust the writer

Claude Simon – it was rather the contrary, but stop.

As far as I can tell Zhang Daqian really does seem to be an interesting artist, multi-faceted and capable. But

I suspect that much of the international fuss made about him is based on very superficial views. What seems very

suspicious to me is the general, perhaps also exaggerated praise of a superstar that goes along with a total disinterest

for artistic detail (the worst sacrilege possible!). And one would expect that people venerating this superstar would

care about the subtle interplay between image and poetry (that seems to be there), but rarely the art of Zhang Daqian is

made transparent, to a Western audience at least, on that level. It seems rather that people like to admire an alleged

synthesis of Eastern and Western art (while the same people do not seem to know that this kind of marketing is hardly

new, because other artists have long been presented as such, and been associated with such ›brand‹ in the past). It

rather seems that artists representing such synthesis seem needed and wanted. But this does not say much about Zhang

Daqian, who, roughly in the middle of his life, got exiled, and half of his life lived abroad, far away from Chinese

mainland, and could also be seen as someone brutally torn between tradition and contemporary art in the era of

Postmodernism.

Did Zhang Daqian ever feel ›haunted‹ by James Cahill? It does not seem far-fetched to ask this question, since what

Cahill did, could also be seen as highlighting the internationally active criminality of a forger, who, perhaps,

may have been simply in need of money, to sustain a large patchwork family in various countries (such as Argentine,

Brazil, the US and Taiwan). But the general picture of Zhang Daqian is that of a charismatic, amiable, sociable, funny

guy, although it is not that difficult to find also critical voices, which, however, seem to represent a small minority.

But one does also hear that he was spoilt to the extreme and very egocentric (and the pupil who said that lived

near him for some time, observing him from close).

The question if Zhang Daqian ever felt haunted, can be answered affirmatively. Apart from the fact that Zhang seems to

have addressed personal and also painful memories in some of his pictures) he had left China, when the Communists came to

power, and it seems that he left China because the Communists came to power. After the ›opening of China‹ in the era

of Nixon and Kissinger, Zhang Daqian left the US, apparently disagreeing fiercly with the US policy of establishing

relations with the People’s Republic of China, resulting with him in settling now in Taiwan, where Zhang was to live till the

end of his life. While Zhang Daqian might have become a superstar on the level of the international art market, this

superstar seems to be a rather unpolitical one. But the whole existence of this exiled painter had to do with the

political situation on the international stage, and also at China. And it will be interesting to compare Zhang Daqian

and Picasso, for once, on that level. Because also Picasso was exiled – from Franco Spain, and to some degree ›recreated‹

a Spain around him. But this never went thus far as it went with Zhang Daqian, who not only lived in/with Chinese

communities abroad, but also used to build Chinese gardens and homes, and – for many – embodied the Chinese painter per

se, whereever he walked. Although one could also say that he fashioned himself as a literati painter (which is, as a

social figure that had existed in specific social contexts in history), who actually lived, at closer inspection, a very

postmodern life, or better: the lives that a postmodern world demanded him to live, or: was offering him to live.

Zhang Daqian in 1955-1957

1955

While actually having built a home in Brazil, Zhang Daqian visits Japan in 1955, where he publishes books dedicated to his own collection of works of art; he also exhibits own works in Japan and visits Taiwan.

Cahill: »I met Chang first in Kyoto in 1955, when I was a Fulbright student and he had come to work with the publisher Benrido on the four volumes of reproductions of his collection, Ta-feng-t’ang ming-chi. He was staying at Kyoto's most elegant ryokan, the Tawaraya, and I visited him there. Since he had studied textile making in Kyoto for two years from 1917 and had been back to Japan often since then, he knew the city well, and spoke some Japanese, so that we could communicate; also, he was traveling with the art critic Chu Hsing-chai, who served as his English interpreter. My memory is of sitting with Chang drinking tea and talking about particular paintings; he had a brush and paper in front of him, and was sketching passages from them as we talked – I would ask ›What do you think of the so-called Ch’ien Hsüan [Qian Xuan] in Detroit?‹ and he would do a detail from it, perhaps a frog and dragonfly, as he replied. This was my introduction, and an extremely impressive one, to his extraordinary visual command of the whole past of Chinese painting.«

1956

In Tokyo Zhang Daqian exhibits his copies of paintings from Dunhuang that, afterwards, are exhibited in the Musée Cernuschi at Paris; also at Paris, in the Musée d’Art Moderne, 30 of his own works are shown; Zhang travels to Switzerland and further travels in Europe; in July: meeting with Picasso at Cannes, an encounter that often has been mythologized as a seminal encounter of two artists representing East and West; the Paris based Chinese artist Pan Yuliang creates a Zhang Daqian bronze bust.

Cahill: »[…] in 1956, the Honolulu Academy of Arts had purchased the ›Sleeping Gibbon‹ with a Liang K’ai signature; I saw another version in the collection of the Falks in New York. […] One of the collections in Kyoto to which Shimada had introduced me during my Fulbright year there was that of Professor Ando; and in it was the painting that served as a source for both forgeries: one of a pair of pictures of gibbons attributed to Mu-ch’i. It had been published in Kokka magazine in 1926, and I assume that Chang made his forgeries from that reproduction, although it is possible that he saw the original in Kyoto.«

1957

Via Hong Kong and Japan Zhang Daqian returns to his Brazil home, a farm that includes a Chinese style garden (Bade Garden), where he has been living since 1954; he suffers from problems with his eyes; problems that on the other hand stimulate him to develop a new ›splashed ink and color‹ technique.

Cahill: »In 1957 the Musée Cernuschi in Paris acquired the ›Horses and Grooms‹ handscroll ascribed loosely to the T’ang master Han Kan, which was said to have been bought by Chang Ta-ch’ien from a local official while he was at Tun-huang. According to a colophon written by P’u Ju, it had been discovered in 1900 in one of the caves. I had been able to see it when I was in Paris at the beginning of 1956, and now recognized it as one of my growing group.«

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS