M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

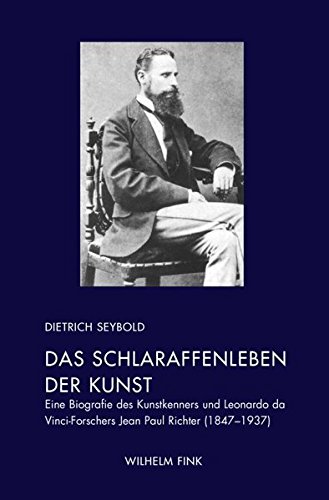

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

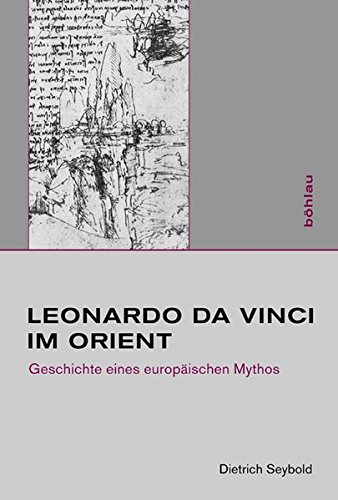

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Three Scenes of Connoisseurship

Three Scenes of Connoisseurship

This is about three symbolical scenes, i.e. about scenes being of a symbolical meaning for the history of connoisseurship. One might call them also mythical images, but here it is more about analysing the narratives – the how these scenes were and are still being told (because this is about often, maybe all too often quoted images, that for once are put here also under scrutiny. We ask what the narratives may be hiding, about the historical context of these scenes and not least about the function of these myths.

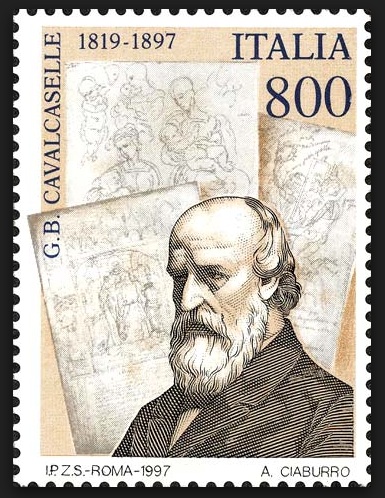

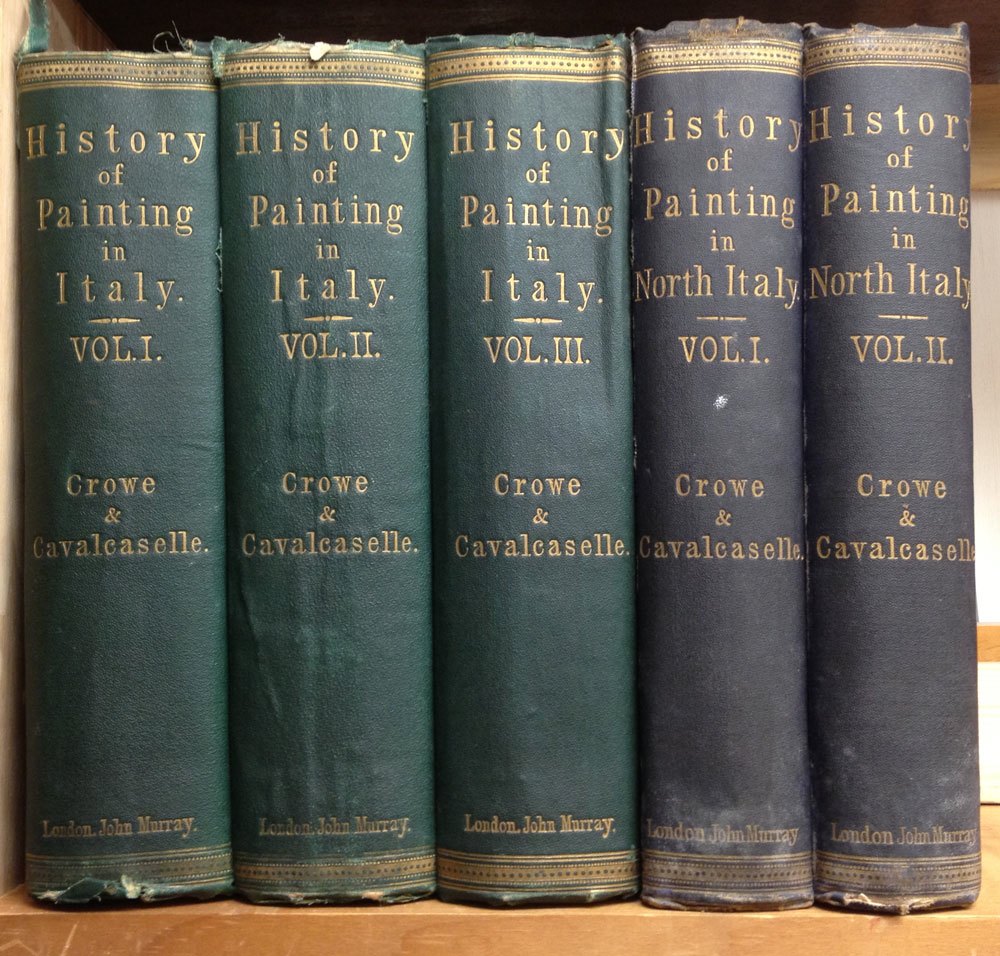

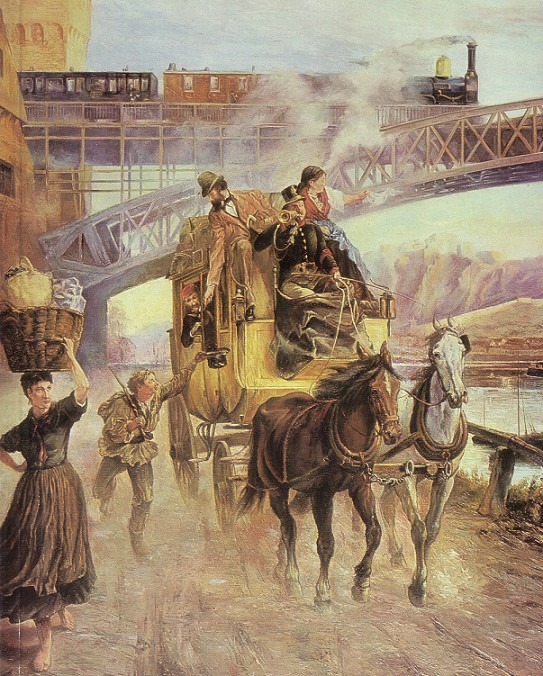

One) Joseph Archer Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle Team Up or The Stagecoaches and the Railway between Hamm and Minden

(Picture: artearti.net)

(Picture: Yann Caradec/flickr.com)

In his memoirs of 1895 English journalist and writer Joseph Archer Crowe recalled his first seeing of his later collaborator Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle:

»He was about seven years my elder, with black hair and beard, a coloured complexion, Italian, an artist. He was, as we immediately found, going round the world, though not as a globe-trotter. He was a painter who had given up painting, as he told us in picturesque but broken French, who had determined to look at those pictures of his countrymen which had found their way out of Italy, and to compare the lost treasures of his country with those which still remained at home.« (p. 65)

(For full text see here.)

What later resulted in voluminous books, in a history of Italian painting that might look like a fortress (later attacked by Giovanni Morelli), was the actual teaming up of Joseph Archer Crowe and Italian connoisseur Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle. Both having, by the way, a painter’s history. But why is it about the means of transportation here? Because the often recalled first meeting of these two men that led to the later teaming up occured at a stagecoach relais station between the German cities of Hamm and Minden in 1847. And it might have occured as well, if the railway between the two cities had opened a little earlier (it opened in October of 1847), but it might have occured in another way, because at such relais stations the passengers were not free to choose with whom to share a Postkutsche, and the account of the first meeting of these two men would have been a different one. And not one that implicitly speaks of having been organized and orchestrated by fate.

Joseph Archer Crowe (1825-1896)

(Picture: doullbooks.com)

What had these two men actually in common when they first met, one might here begin to ask. Cavalcaselle’s French was, as mentioned, picturesque and less than fluent. Crowe, on the other hand, had lived in France (see: http://eyrecrowe.com/biography/life/), because his father had moved there with his family and worked as a liberal journalist. And in 1840 Joseph Archer Crowe had even entered, following his elder brother, a Parisian studio. He would later, in 1852 and in his 1895 memoirs, picturesquely describe the studio of painter Paul Delaroche. To the right above we show the 1840 version of Napoléon 1er à Fontainebleau le 31 mars 1814 that is in the Army Museum of Paris. A picture that might inspire another question? How were the two men thinking politically at the time, in 1847, the year Giovanni Morelli allegedly did publish a newspaper article that displayed his (then) enthusiasm for Pope Pius IX as a possible godfather of Italy’s unification? Europe was one year away from another chainreaction outburst of revolution. And the two men in 1847, that both had left painting, as a profession, behind them, were meeting, because both were heading to Berlin to see pictures.

(Picture: briefmarken-forum.com)

Crowe was already committed, like his father, who was actually with him on that trip to Berlin, to language as he was to painting, having joined the staff of the Daily News in the 1840s, the newspaper founded and briefly led Charles Dickens. And The question of language inspires here still another question: how did this teamwork actually work in later years? Contemporaries thought of Crowe more as the translater of Cavalcaselle’s thoughts. But Crowe’s role was apparently a more substantial one, at least the one of an editor of scattered notes that had to be brought into a structure, not to speak of literary form. And it does not seem that their common work has ever put under scrutiny as to the vocabulary and literary style, as to the interpretation of what an Italian connoisseur had tried to make out of his thoughts and observations in front of pictures, probably guided by, but we don’t know this exactly, notions and expressions someone had once taught to him. But the actual teaming up ocurred much later anyway, when both men lived in England in the 1850s and after the European revolutions of 1848/49. Yet this teaming up had its own history, and this history begins at a stagecoach relais station (we don’t know, which one) between the two all-known cities of Hamm and Minden.

(Picture: briefmarken-forum.com)

Crowe had travelled to Hamm, apparently, by train. In 1847 Charles Dickens, Crowe’s former editor, was publishing a novel that not least was about the railway, a technical novelty, a spectacular sensation as to speed and energy, but also much debated as far speculation was concerned – and the destruction of landscape, or at least of structures that had grown for long and over time.

Had the two men now met in a railway wagon (but what if they had’t?) they could have spent much more time together. But what did actually occur, between Hamm and Minden, and later between Minden and Berlin, was a meeting, not apt for an actual teaming up. But, as it was interrupted from time to time, by the rhythm of the changing stagecoaches at various relais stations, it was an ideal way of gaining a first impression. Of rethinking the impression. Of gaining another impression. And in a railway wagon one would have met in a completely different way that might even sooner have led to an actual teaming up. But for a first encounter of two men dedicated to pictures – fate actually did take an interest in. But it did not force the two men to spend much time together – but rather invited them to think about a first impression, followed by another impression, and this all under a bit ludicrous circumstances of travelling by stagecoach, but organized (or imposed) by the organization of the postal service in the Germany of the Deutscher Bund.

The Altes Museum in the 1850s

If the two men, when having arrived finally at Berlin, looked back upon the travelling by stagecoach, they probably were already aware that the age of the Postkutsche was coming to an end. But they certainly were not aware that their first meeting under these circumstances now found its following in quite a comparable way. Because they were now to meet again in front of a (and not in) museum, and under the circumstances organized by the way the Altes Museum of Berlin, where the collection of pictures was housed, at the time was organized.

Crowe had been out early. For smoking a cigar on the boulevard Unter den Linden he did, as he tells us, »narrowly« escape arrest (as we see below, a or even this cigar is given him as an attribute in his portrait). A few minuntes before ten o’clock he found himself in front of the Museum »waiting for the opening of the doors«.

»Who should appear, with a note-book in his hand, but my Italian fellow-traveller! He confided to me that he had come to Berlin to study the Italian masters in the Museum; I confided to him that I was going to do the same thing for the Flemings. We entered. He turned to the left in the gallery, I to the right.« (p. 65)

Crowe stages the scene a trifle like a comedy. One might imagine the two men running in opposite directions. And it is the Italian, it is Cavalcaselle who actually makes a first move fowards Crowe. A first move towards a negotiating a teaming up. Because it’s him who returns, from the wing of the Italians. And by that time, and according to Crowe’s account, the two had exchanged not even names, nor profession or address:

»Presently I saw him running in my way. Breathlessly he called on me to follow him, give up my stupid quest of the Flemings, and come and look at a wonderful masterpiece on the other side. But I had already found the panels of Van Eyck’s Agnus Dei (see: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genter_Altar), and was lost in admiration of them – so much so that I stopped my friend and tried to persuade him that he was prejudiced; and, to my surprise and great pleasure, I gradually saw a smile of enjoyment playing about his features. He looked at the pilgrims and hermits riding and marching to the adoration, and he burst out at last with the confession that he had never seen the like by a Flemish master.« (p. 65f.)

The teaming up is still somewhat in question. But it is the Van Eyck which acts here as the patron of the future bond. It is the common passion (and note the »smile of enjoyment playing« about Cavalcaselle’s features and compare with the material assembled in the sections on the iconography of connoisseurship). What if the Van Eyck had not been brought to Berlin? But it is there, an essential, even central element of Crowe’s narrative, and it is more than fate, it is a almost divine light that plays about the scene. Years later a book on the Flemish painters, the first product that resulted from the teaming up, was to follow in 1857.

At Berlin, in 1847, the story of the teaming up in steps goes on:

»We spent the day together, made closer acquaintance, communicated to each other name, profession, address, and next day Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, for so he was called, dined with my father at the Hôtel du Nord, and we all went to hear the Freischütz together at the opera. Once again we met, and then shook hands – I bound with my father to Vienna, he proposing to take some other route.« (p. 66)

A route into the revolution of 1848/49, i.e. into Italy’s first war for independence for Cavalcaselle. According to what he later told his friend Crowe, Cavalcaselle escaped only narrowly from being executed by the Austrians. But they did team up, after having met once more in Paris, by accident (but is one to call it still »by accident«)? And finally when both men were living in England.

On Eduard Gaertner’s Unter den Linden of 1852 we see, from the center a bit to the right, the Staatsoper. In 1847 the smoking of cigars on the street was indeed forbidden, although cigars could also be bought in shops Unter den Linden. In Munich in 1847 an Englishman got actually arrested for having a cigar in his mouth while passing a guard and not reacting to the guard’s calling him in German, although apparently an actual prohibition did not exist). To the Altes Museum we have to go straight up and then to turn to the left.

The story may be put under scrutiny for further details. It also may be questioned for its narrative as such. But the story, as Crowe recalls it in his memoirs, assembles a number of details, which all can be seen as tiny glowing centers in themselves. The cigar may one make to think that the revolutionary year of 1848 did start, in Milan, with a provocative »tobacco strike«, that, tragically, got out of control during the first days of the year (with Giovanni Morelli being an eye witness).

Two) The Finding of a Method or The Sala Botticelli as a Theatrical Stage

The only account about the when and about the how Giovanni Morelli allegedly did find his notoriously famous method stems from Morelli’s actual apprentice Jean Paul Richter (1847-1937). And it is this account, not about an invention by the way, but more about a finding »by accident«, that we will have to put under scrutiny here. About the when Richter does not give us precise informations. Because it is after his speaking of Morelli having spent »most part« of the 1850s seclusively at Bergamo – concerned with historical studies in the beginning, but more and more inclined to the study of the history of Renaissance painting and from the beginning with a feel of dissatisfaction as to the state of affairs in attribution – that Richter goes on to render the following scene:

The Sala Botticelli today (picture: uffizi.org)

»It was on a visit at the gallery of the Uffizi at Florence, when he [Morelli], contemplating the paintings by Botticelli, made the observation that for the numerous figures in one and the same painting the hand as well as the ear was modelled in a strikingly corresponding way [in auffällig übereinstimmender Weise]. And this observation found its confirmation in an examination of other paintings by the very painter. In continuing these studies it became apparent that in the works of Botticelli’s pupil, Filippino Lippi, the apprehension or form of the extremities, especially the hand and the ear, was a different and yet again characteristic [eigenthümliche] and independent one. The investigations expanded to the certified [beglaubigten] works of the other Florentine masters effected a same result. In singular cases, when the method was failing, it became apparent that the designations of the pictures were unsatisfactory or poorly certified. The getting of results at Florence prompted Morelli immediately to do the same investigations in the other artistic centers of the country, at Perugia, Siena, Bologna, Ferrara, Venice, Verona, Milan and at other places.«

As to the »when« Morelli himself provides us with another information: Because it is in May of 1885 that he tells Richter in a letter, that »about 25 years ago« he had still been looking at pictures judging them by the mere »general impression«, yet feeling a »discouraging uncertainty« as to attribution. And that it had been this feeling of uncertainty that had led him to the »Lermolieff’sche Methode«. »About 25 years ago« – which would give us a date of 1860 for the pre-Morellian state of affairs that had still been prevailing.

Four years earlier, in 1856 Morelli had been asked to join the staff of the newly founded Eidgenössische Technische Schule at Zurich that had opened its doors in 1855 – and not as an art historian (this was to be Jacob Burckhardt), but as a professor for Italian literature.

This might give us a first hint that it is complicated with the professional career of Giovanni Morelli, and it is precise to say that he had many professions during his life, but the actual profession he did never find (or only later, when he published his writings on Italian art, from 1874 onwards, when he was 58).

But in 1856 he was exactly 40 years old and not a little embarassed by the request from Switzerland. And this for complicated reasons.

He actually was Swiss still at the time, since Italy, that he felt was his homecountry, did not yet exist. And he was driven to literature, at times much more than being driven to the visual arts, but driven to be a writer himself and not being a teacher of literature. Thus, for a number of reasons, he declined in 1856. But this was not yet the actual decision for a life dedicated to the study of the visual arts. It is even more complicated.

Because in 1857 he still wished that some of the plays he had written from the 1830s onwards, would be represented on an Italian theatrical stage (he mainly thought of Turin) and he asked the epochmaking literary critic Francesco de Sanctis for his opinion about three of them. De Sanctis owed him something because it was him whom Morelli had recommended for the chair at Zurich that de Sanctis actually took for some time. And this is about the last we hear as to Morelli’s three comedies. Because in 1857 it is still »dramatic studies« and the study of pictures that concerned him – in 1858 it is only the latter. And in sum: What Richter tells us might be broadly correct, but occurs under very complicated circumstances. And we haven’t even reached the year of 1859, which brought the Second Italian War of Independence – and independence in 1860. But this meant not only the joy of patriot Morelli, but another request he was somewhat embarassed again – the request of being the representative of Bergamo, the city that he considered to be his home. And he did not flinch from it.

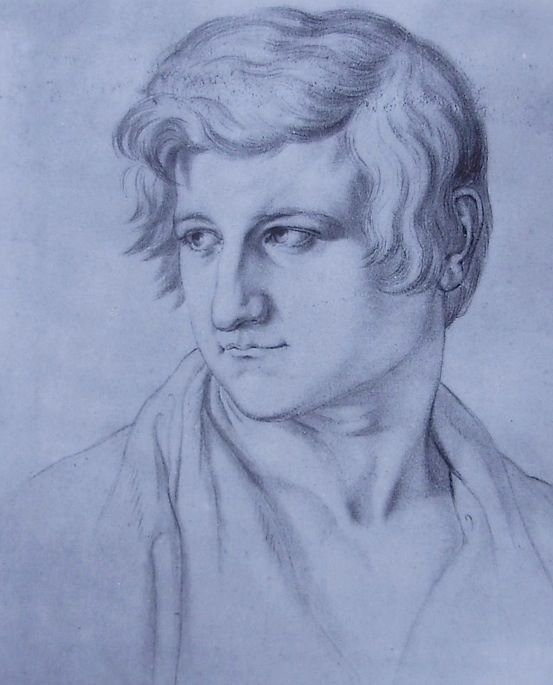

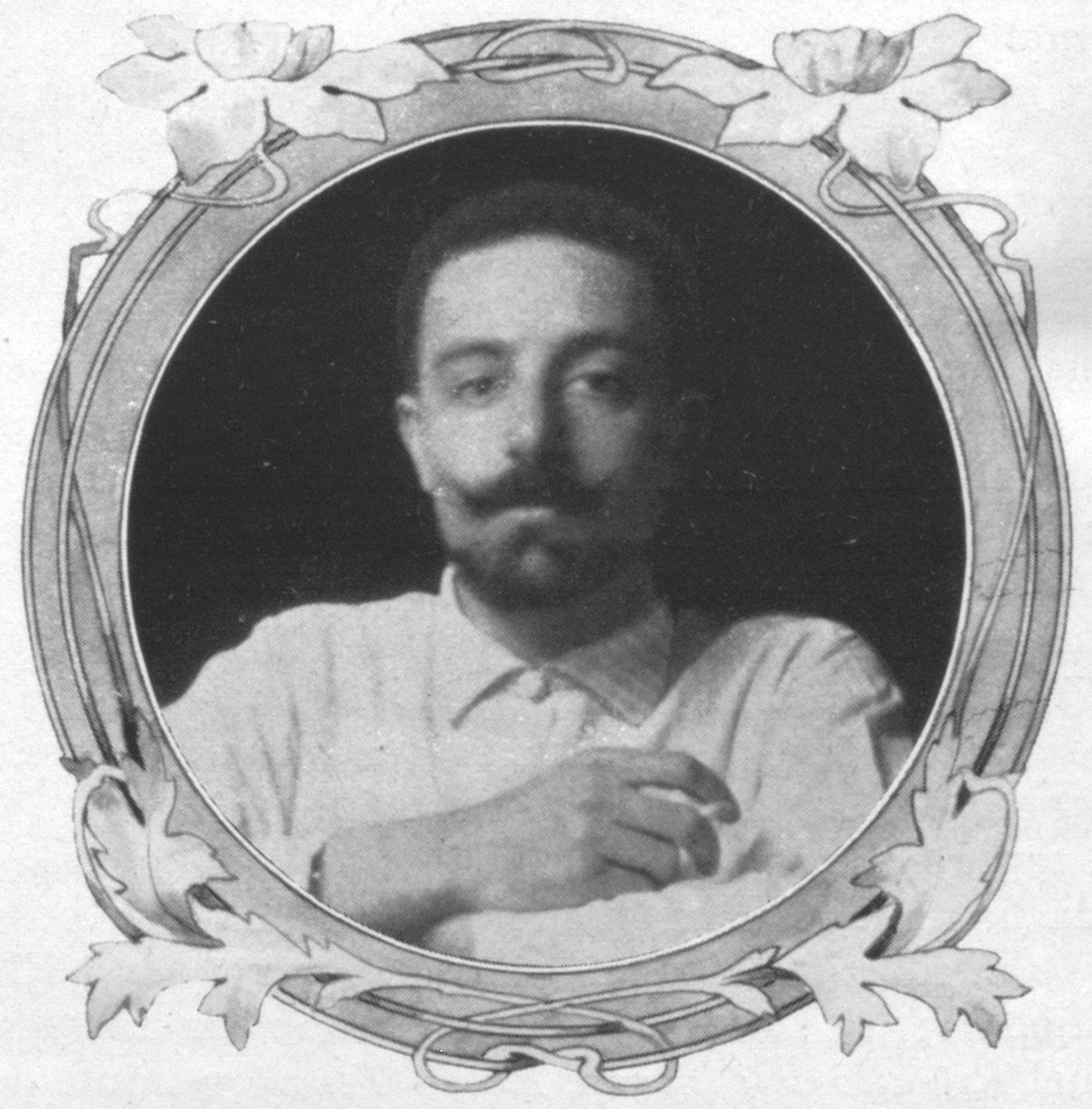

Francesco de Sanctis

Having roughly sketched the historical and biographical of the symbolical scene of the Uffizi (you will find more about in in my forthcoming Morelli-portrait) we realize that the theatrical stage of the Sala Botticelli is still rather empty. By which we mean that, according to the Richter narrative, Morelli worked out his methodological guidelines all by himself, as a solo artist, one might say, and that he found a method either »by accident«, and even, as some Morelli scholars have it, did »invent« connoisseurship all by himself. But this version does not bear testing, although we concede that many of the dramas Morelli’s life was made of were rather silent dramas that he preferred to deal with all by himself. But we simply proceed here by assembling some of the major influences and the people that represent those influences on that stage as well – next to Morelli and interacting with him.

Giovanni Morelli as seen

by Bonaventura Genelli in 1837

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 114)

First of all we have to say that Morelli, in his youth, found connoisseurship to be something rather crowded by fools. Which also means that he accepted that there was »real« connoisseurship and not the whole was pretentious in itself. But at the time, when being a young student, he rather thought of painters, and some of his friends were painters, being the »real« connoisseurs. In 1846 he pledged, however, never to enter a gallery or art museum, accompanied by so-called connoisseurs. Because it did bother his enjoying of art being pointed to some minor details, the little mistakes, artists do as to anatomy etc. And with this more or less serious pledging he was referring to a little argument he had had with one of his best friends, namely Giovanni Frizzoni, who had died early, in 1849 and because of an infection, but represents an early influence on Morelli. But complicatedly, at the time, Frizzoni did point to things that, at the time, Morelli did not wanted to hear about.

His experiences with comparative anatomy as a student, of course, add to this early experiences, but it is, for quite a long time, not Morelli’s aim to become a connoisseur himself.

One major influence, during the 1850s, was to become Otto Mündler, and it was to large degree Mündler’s influence that Morelli’s passion for the visual arts renewed at all. Because he thought, as we have said, to be a writer, but started now to collect works of art as well. There was no actual need to be an expert himself, but he enjoyed the studying with Mündler and others, after 1860 especially with the restaurer Giuseppe Molteni as well (who, however, as a restorer, tended to correct these little mistakes the artist falls in as to anatomy… and thus can be seen as another individual influencing Morelli’s methodological thinking).

But as one of the major influences on Morelli we also have to recognize the literary tradition of connoisseurship as well. And Morelli, although he did not like to acknowlegde his predecessors (and even less, if they were Jesuits, like Luigi Lanzi knew this tradition rather well. If we go back in time we find Morelli not only reading Carl Friedrich von Rumohr, but even meeting him. We find Morelli reading Passavant, Mariette, Baldinucci etc. etc. And even the various elements that make the whole of Morelli’s practices as a connoisseur, that make his method, can be traced back into this tradition of connoisseurship. Morelli did even know the name of Richardson by 1836, when he was only 20 years old, but here we have to concede that he probably had come across the name by reading Winckelmann, because the English language, he did, it is true, read, but it was not one of his preferred languages. The search for the influences on Morelli could be proceeded, but it is enough here to say that the Sala Botticelli of the Uffizi might have been empty as a stage, but inside Morelli’s head all these influences, recollections, experiences were coming together. And it is possible to think of the interaction of all of these influences as something theatrical. Not least because Morelli did occasionaly like to enter into a little argument with this or that predecessor (as for example with Rumohr) in his later books.

We will discuss what Bernard Berenson has to say about Morelli as a connoisseur and as a politician below. And we like to finish here with underscoring that the finding of methodological principles (which are not to think as a coherent system or of exact procedures to follow) occured over long spans of time. During the 1860s Giovanni Morelli acted as the representative for Bergamo, and he did turn to cultural politics especially. But another of the many silent dramas that made his life, was his urgent need of money, especially during the first half of the 1860s, which, for Morelli’s household – he had an income on land and indirectly on silk production on that land – brought economic crisis. This reason added to the other reasons, be they scientific, idealistic, patriotic, that explain his turn to connoisseurship and to be a marchand amateur at this very time. And for this profession, or replacement of profession because of loss of income on land, certainty as to attribution of pictures was urgently needed, and therefore methodological reflection. All these reasons together made a complicated mix of, partly contradicting, reasons for a turn to connoisseurship, long after young Morelli’s feeling the urge of ridiculing foolish connoisseurs in a theatrical play (a play that for understandable reasons he later did not like to be reminded of). But if something has to be made clear it is that scientific connoisseurship, as represented by Giovanni Morelli, decidedly was not merely the outcome of a truthseeking idealism. This idealism was part of it too, but as we think we have made clear it was the outcome of complicated circumstances, and among other things the outcome of one individual’s biography who led a complicated lifelong struggle for its own identity. The connoisseur’s role was one role that Giovanni Morelli took on during his life, and especially in his later years, but it may have been his life’s main role, and even more so in retrospect, but on the other hand it was never a role that Giovanni Morelli considered himself as a role without alternatives or as the one role that ever did perfectly fit.

From Morelli to Berenson

Three) A Rickety Table Outside a Café at Bergamo or Enrico Costa and Bernard Berenson (not to mention Charles Loeser nor the White House Cézannes)

The main and maybe the only witness was dead for 29 years, when almost 76year old Bernard Berenson, in February 1941, recalled a declaration of seemingly youthful idealism: »You see, Enrico…« goes the familiar tune, about dedicating one’s life to the noble and merely scientific task of finding out who painted what. Familiar because so often quoted, and rarely put under scrutiny, this famous tune stems from Berenson’s Sketch for a Self-Portrait (published only in 1949). And since Berenson accused himself of being guilty of all crimes in his old age (which might mean that he actually was guilty of none), we have to be especially careful here.

What if, for once, we would consider Enrico Costa as Morelli’s heir, as his actual successor, and not Bernard Berenson? Enrico who?

Enrico Costa was one of two young men that Jean Paul Richter, Morelli’s apprentice, provided with introductions to Giovanni Morelli in 1889 and again in early 1890, and that he introduced even to each other, as he says in January of 1890. They went to see Morelli in 1890, and although Morelli’s speaking joyfully of both of them due to their passion and dilligence, one thing he later said to Richter was also: Take care of this Costa – he does deserve it. And this he does never say of Berenson.

Morelli might have seen both young men as promising students of art, but Morelli and Berenson, on occasion of their few encounters did not exactly hit it off. This is was Berenson felt himself, if he was saying, in a letter of the time, that Morelli wanted to be treated as a master. And even more frank: that he could not really talk to him. Much later in life he also recalled of having been proud and shy in his earlier years. And this sounds like Berenson, then, in 1890, having been wanting to show Morelli that he was not only preparing for becoming of something like a connoisseur, but also showing that he already did know this or that (Morelli agreed to that, by the way, in referring to Berenson’s first visit in January 1890, and in, as it were, conceding that the young student had already brought it quite far). One may remind here that Jean Paul Richter, about fourteen years earlier than Berenson, had found his way to deal with Morelli and into a close and fruitful cooperation, just because it had been absolutely clear who was the revered master and who the thankful pupil who did not know anything, but was more than willing to learn.

To speak about Berenson and Costa is, if it be allowed to take a comparison from sports, a bit like talking about Pelé and Garrincha. There are careers, brilliant careers, and there are biographies one may also call careers, but these biographies representing rather the somber, less brilliant, but still significant sides of a sport (and of a society a particular sport is embedded in). And it is not necessarily wanted by those who are admirers of the brilliant careers to be reminded of the biographies of those who fail. Because it’s these very biographies that remind that the forces or circumstances that lead to a failing in one case are to be found in the more brilliant careers as well (if only in terms of dangers). But those who identify with connoisseurs like Berenson did certainly rather not want to hear of Costa, who in some ways did tragically fail. And they certainly do not want to hear of Morelli finding expressively so Costa being worthy of further support.

What Morelli said – it may sound somewhat strange here – might have had to do with the fact that at the time Costa was well-to-do, if not saying rich. While on the other say, one may add, that Berenson was at the time poor as a church mouse. Costa could not only afford to travel, this is what Morelli probably was also referring to, but he could also afford to buy art and to collect. While the circumstances under which Berenson lived at the time when he was introduced to Costa were to be described rather as precarious. Because he was not standing on his own feet, and being supported by rich Bostonians, who were also potential (and even at the time) not only potential buyers of art, was only one step away of advising these Bostonians about what to buy, more as a favor and due to thankfulness, and still another step away from taking a fee for doing so, and only one or two steps away from taking 25% of the profit for selling a work of art that had been authenticated by Berenson.

Robert Hughes (picture: haddonpearson.blogspot.com)

When art critic Robert Hughes in 1979 reviewed the Berenson biography by Meryle Secrest and the first volume of Ernest Samuels Berenson biography for The New York Review of Books he obviously found himself, judging from the verve of this remarkable review essay, to be enthralled by the drama of this biography. Calling Berenson one of the savviest men who had ever lived, Hughes referred, among other things, to the ways Berenson had dealt with appearance and reality. And if one would think – this is what we think now – that to enter the world of Bernard Berenson, the world of Villa I Tatti, then and now, does only mean to learn something about art, one would be falling into the very misunderstanding of taking appearances for real, as many, yet not all, contemporaries and later critics of Berenson did. And it’s these appearances, Berenson was also a master to work with, and not only his eye.

How to be seen was and is the very question, and not only the how to see (and if it was about the teaching of others how to see, would be another question). But one thing seems certain: It’s the key problem Berenson biographers face, it’s the question where to draw the line between appearence and reality (or how to discuss the interactions). For example as to Berenson’s Sketch of a Self-Portrait of 1949. And what we face here is the problem of dealing with Berenson’s strategies to deal with appearence and reality on a level of memoir literature.

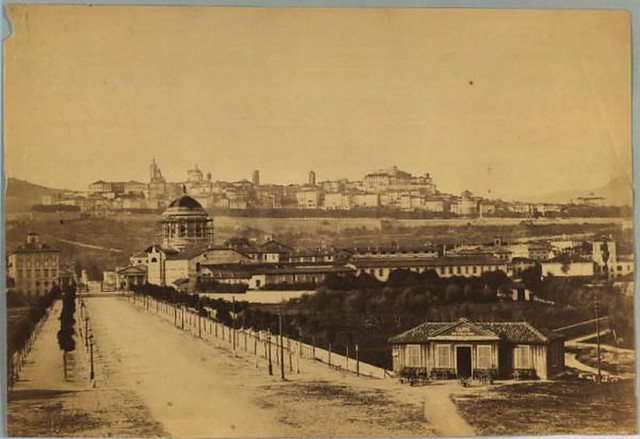

Bergamo bassa in c. 1860 (picture: Paolo Motta/flickr.com)

Paolo Motta writes: »Una splendida vista del Sentierone di Bergamo bassa, allora Via Roma, oggi Via Giovanni XXIII°. Sulla destra si riconosce un bar ristorante, oggi trasformato in un McDonald’s, la cupola di Santa Maria delle Grazie e sullo sfondo la città alta.«

It’s only about the very scene here wherein Berenson quotes his speaking to Enrico Costa when »one morning towards the end of May« sitting at that famously »rickety« table outside a café of lower Bergamo. The year almost certainly is 1890 (and not 1889 as Hughes has it in his essay; because Richter claims of having introduced Berenson to Costa only in January 1890), and because of Morelli’s speaking about having met the two of them in the evening of May 16 1890, about their common enthusiasm for Lorenzo Lotto. And about the two of them already having studied the works of Lotto at Bergamo and surroundings, and of their taking now a train to Ancona to further study the works of Lotto. The scene, if it was only one real scene, that Berenson is recalling in his memoirs, might have occured prior to the visit of May 16th, or afterwards, »towards to end of May«. But the common enthusiasm for Lotto is there, the very town of Bergamo is there and it seems rather difficult to situate the scene in other years. The question of dating, however, is a problem, because the background of 1889 might have been a more innocent Berenson, but gradually this innocence is vanishing, and a declaration of youthful merely idealistic truth-seeking connoisseurship is something else if set against an more innocent or less innocent background.

A cafè at Borgo San Leonardo (picture: borgosanleonardo.org)

In any case the only one who speaks in that scene is Berenson, and Costa acts only as a silent listener. And in a way Berenson silences the only witness of his speaking, because at the time the memoir was written, Costa was already dead for almost thirty years (having died in December of 1911). »Were I writing memoirs«, Berenson says, »I should have a great deal to say about him«. And we note that the Sketch of a Self-Portrait was not meant to be seen as a memoir, nor that Berenson ever said a great deal about Enrico Costa. And while Berenson goes on to stage his own entering of connoisseurship, given his own high aspirations, as a failure (yet vaguely stating that it brought »material advantages«), he uses Costa as the mirror image of his own idealized self, owning the great qualities Berenson himself was lacking, but after all remaining silent about Costa’s later life. And given the numerous quotation of the passage, as the central message most readers have understood to be the following passge:

»I recall saying ›You see, Enrico; nobody before us has dedicated his entire activity, his entire life, to connoisseurship. Others have taken to it as a relief from politics, as in the case of Morelli and Minghetti, others still because they were museum officials, still others because they were teaching art history. We are the first to have no idea before us, no ambition, no expectation, no thought of reward. We shall give ourselves up to learning, to distinguish between the authentic works of an Italian painter of the fifteenth or sixteenth century, and those commonly ascribed to him. Here at Bergamo, and in all the fragrant and romantic valleys that branch out northward, we must not stop till we are sure that every Lotto is a Lotto, every Cariani a Cariani, every Previtali a Previtali, every Santa Croce a Santa Croce; and that we know to whom of the several Santa Croces a picture is to be attributed,‹ etc., etc.« (p. 60)

Ambiguously referring to what oneself does might be yet another strategy, after the silencing of the witness, of creating appearences. But the speaking of Morelli (and also of Marco Minghetti) within the actual speaking to Costa that Berenson recalls, is still another matter. Because of what Berenson says of Morelli might be correct in terms of how Berenson saw Morelli at the time. But if he, in the 1940s or even later, still believed to be correct what he writes of Morelli, which is that connoisseurship had been for him a relief of politics (which also suggests: mainly this or: this and nothing else), Berenson either knew very little of Morelli. Or this very passage has to be seen as a deliberate strategy of giving the youthful declaration of truthseeking idealism an air of future professionalism. Whereas Morelli had, be it willingly or as an outcome of circumstances, always remained an amateur. In any rate the speaking aims for contrast. And what the young (or old) Berenson (speaking or writing) completely lacks of acknowledging is the political dimension that connoisseurship had for Morelli in itself (because it was about re-organizing museums, inventorizing the cultural heritage of the country, education, schools of restoring and so on), not to speak about the financial need we have spoken about above.

(Picture: bestofbergamo.com)

But the even more manipulative strategy is or was to profit all of his life from the aura of Morellian connoisseurship as the most advanced and scientific way of professing the business of attribution (supported also by the association with Sherlock Holmes), while on the other hand Berenson did little or nothing to cultivate the scientific standards of connoisseurship, namely as to transparent acknowledgments of all the reasons that did speak for or against an attribution. In later years, still claiming or suggesting to be a Morellian, Berenson did explain nothing at all, nor made his methods transparent, nor did explain why he had left behind him, what once had been the ambition of Morelli – to work towards a future science of art, based on connoisseurship. And the result being that, today, art history is based on something whose scientific standards are referred to as a »mess«.

The subtlety of the scene that we discuss here, is however the subtle staging of it as a declaration of youthful truthseeking idealism, leaving it to the reader to decide if what Berenson was doing afterwards could be or had to be seen as the actual fulfillment of a promise given on that day to Bergamo, to Lotto, to Costa, to Italian art, to the world or to himself (and he is, at least, suggesting so, because it is embedded into a story of someone, himself, loosing his destined way, of having taken the wrong way by delivering an Opus magnum on the Florentine drawings, in sum: Berenson is suggesting that he had taken the path that his youthful, only wrongly directed, but still merely truthseeking idealism had pointed him to; how exactly he was to make his living was something else, largely outside the frame shown to the reader).

The scene, read for itself, could also be read as ironically giving a promise like a student does who is only imagining what one might do in life, ironically because of the student is already knowing or having a feel for it that life is more complicated than to allow for mere truthseeking idealism. And Berenson, as is rather clear from the circumstances under which he lived at the time, certainly knew much better at this point of time than his memoir does show him to know. The only question is – did the reader know enough of Berenson or not (to adequately judge the scene). And does he know today. After decades have been spent to discuss less the morality of how to deal with appearence and reality, but mainly the morality of how to do business. And it remains to be clarified the passage from the age of Morelli to the age of Berenson within the history of connoisseurship. Because if one does perceive Berenson only as Morelli’s heir, as his successor, one lacks to acknowledge the changes in mentality, in practice and, yes, in scientific and also human ethos above all. And only from knowing Morelli much better one would gain an actual true image of Berenson, namely by using his own strategies, i.e. by deliberately contrasting opposits.

Enrico Costa (1867-1911)

(source: Carlo Gamba, Necrologio [Enrico Costa], in: Rassegna d’Arte 12 (1912), p. IV)

But what happened to Costa, after having left Bergamo, after travelling to Ancona where we left him? Enrico Costa, had been taken under the wing of Jean Paul Richter, and he remained being a well-to-do travelling companion for Bernard Berenson, although tensions led to a splitting of the two after a couple of years. Costa, who probably spent too much of his money and possibly made debts, was apparently forced to leave Europe in 1897 for South America. After lecturing on art at Bogotà, after travelling also in Brasil with Berenson intimate Charles Loeser, he did return to Europe.

»He was half Genoese and half Peruvian, with a slim long face, nose thin and slightly aquiline, delicate sensitive mouth and fine black eyes, black hair too, and of course a dark complexion. His name was Enrico Costa and were I writing memoirs I should have a great deal to say about him.« (p. 59)

(Picture: npg.org.uk)

Some letters to Jean Paul Richter are extant that speak, among other things, also of landscapes he had seen on his trips. But Richter failed in providing an appointment for Costa at the library that was to open as the Bibliotheca Hertziana in 1913, although the coming back to Europe probably had much to do with giving him this future perspective. Costa then joined the circle of Charles Loeser and Carlo Gamba. And died, rather unexpectedly, aged 44, in December of 1911. Gamba’s obituary speaks of his great talents, his enthusiasm, and quotes from letters that might be extant somewhere, but all in all the personality of Enrico Costa, Count Costa, as he was, has drawn little attention. Although here in there one does encounter his name among those early collectors of Cézanne, that as early as in the 1890s bought some pictures (according to Gamba, Costa, who had been born and raised in Paris, was in possession of one or more works by Cézanne as early as by 1892). And it might well be possible that the interest for Cézanne that existed within the Berensonian world of connoisseurship, more represented however by Charles Loeser than by Berenson himself, could be, if more information was available, traced back to Costa.

One of the works by Paul Cézanne, once owned by (Count) Enrico Costa.

This one’s being now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

(picture: metmuseum.org).

And we finish by speculating that, indirectly, even the bequest of works of Paul Cézanne, owned by Charles Loeser, to the president of the United States (it has become common, recently, to speak of the White House Cézannes, although the story is more complicated), might have had something to do with the, as it appears, difficult life of a passionate student of art that, however, did not manage to pursue, not to mention of actually making something like a career.

Back to the starting page of Dietrich Seybold’s homepage: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/HomePage

Charles Loeser (1864-1928)

(picture: itatti.harvard.edu)

© DS