M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

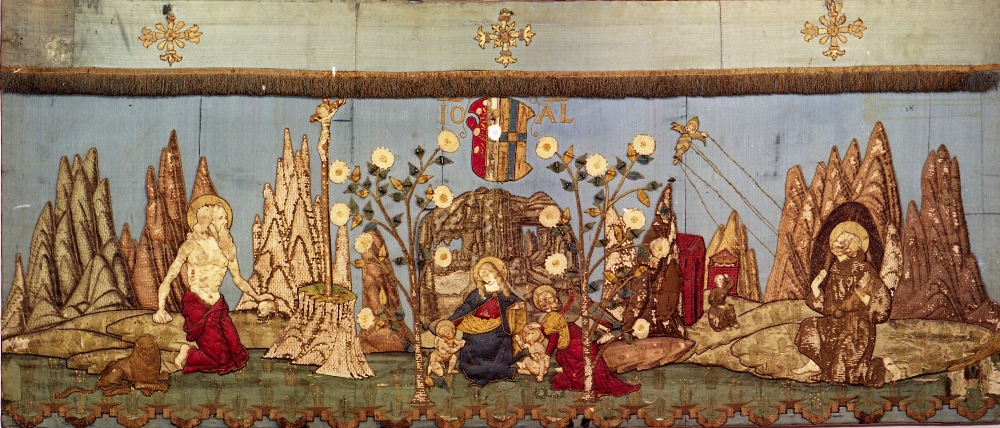

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Leonardeschi and Landscape  |

See also the episodes 1 to 18 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

A Brief History of Digital Restoring

And:

Leonardeschi and Landscape

(12.9.-14.9.2021) Autumn is coming. It is time to take a deep breath; and we are going to contemplate landscape.

›Landscape?‹, I hear my readers mumbling. ›Isn’t that boring? Isn’t this book supposed to be about Salvator Mundi history?‹.

It is. And the contemplation of landscape is supposed to be boring? How puerile. The contemplation of landscape can be as

wonderful as listening to your favourite song by Guillaume Dufay (you don’t know him? – then it is going to be hopeless).

And there is so much more in landscape. What I want to do here specifically is to contemplate the creative flow in and

around Leonardo. Art historians should ask less about influence, or better: ask about influence – but then ask what

someone makes of what he (or she) finds – and name it. This is also what we should ask as to Leonardo. Because Leonardo

is not the origin of everything: he did make something of what he did find. Yes, he was influenced, collected influences,

transformed them, and created. But also the Leonardeschi did. And yes, they are neglected by Leonardo scholarship.

Which is all the more unforgiveable as there is so much to observe. Again I hear my readers mumble: ›we want to hear more

about copyright lawyers, aggressive as mercenaries, while being well-informed about the latest trends, as a fashion

principessa would be‹.

Here is something I found about copyright and Leonardo. Because in fact we have one important source: Ambrogio de

Predis and Leonardo got into a conflict. About Ambrogio wanting to do a copy of the Virgin of the Rocks. But they had

the idea of having a Dominican monk settle their conflict (who does need copyright lawyers if you got a Dominican to

settle?). And here is what was the result: Ambrogio was allowed to do a copy of the Virgin, but he had to share what

he earned by doing that with Leonardo (see Marani 2005, p. 142)!

While contemplating landscape we have to keep that in mind as well. But now I want everyone to take a deep breath and to

comtemplate landscape and to become aware of a creative flow that includes also currents turning away from Leonardo (who

would have thought of that). And of course everything is about the Salvator Mundi as well, but indirectly. It is

about how to handle what you may find as an artist. About what you may borrow, and about the rules artists have given

themselves (to break them). But above all: it is about creative energy as such – the energy of one central since

extraordinarily gifted figure, and about the creativity possible next to such a figure. It is about such influence, and

about what people make of such. This is also what makes a difference in art. And this is exactly the difference

connoisseurship is about. A difference that allows us to ascribe authorship (if we have to). And about specific qualities

that we should acknowledge in their own right, apreciating them – for appreciation’s sake. As we should appreciate

the contemplation of landscape for landscape’s and for art’s sake. Here comes the nineteenth episode of our New Salvator

Mundi History.

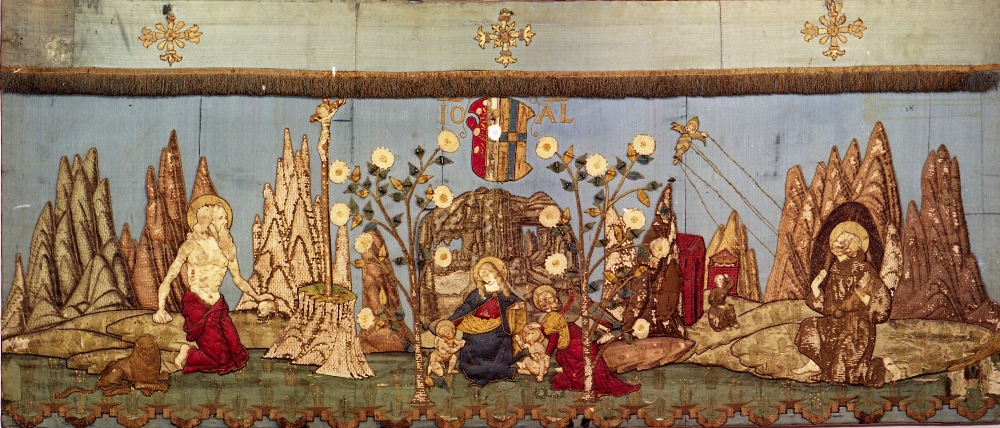

(picture above and in title: Sailko / Marco d’Oggiono; detail from; also title: museobaroffio.it)

One) Zooming Out and Zooming In

Let’s start with looking at a bud of modernism – at the time of the Renaissance. Our first example is the so-called

Paliotto leonardesco of the Museo Baroffio (Sacro Monte sopra Varese) (picture above: museobaroffio.it). ›Paliotto‹ means

›altar cloth‹.

It is dated c. 1490. We see that the Virgin of the Rocks-design has become an element within a wider conception as

well as within a new approach. One might say that we see a stylized abbreviation of Leonardo’s composition, an

abbreviation, almost a logo, that works within a less realistic or illusionistic whole. A whole that has perhaps more to

do with Gothic styles (or rhythms). But – and this is the ›but‹ of post-postmodernist viewers of the 21st century,

who can look back at all styles, but particularly at classic modernism after 1900, i.e. at all the isms that turned

away from academic mimetic art (including central perspective), and turned to styles that, in turning away, yet

remained linked to the tradition.

Looking at the Paliotto – it seems to say: ›we have seen Leonardesque atmospheric realism and illusionism now – we keep a

memory of it, but now let‘s turn to something else‹. This I would call a bud of modernism. It never blossomed (one may

assume), because no institutions supported such blossoming. But it is there. And it does remind of an rather early and

immediate zooming out in a double sense. A zooming out that results in a ›wide shot‹, a panoramic view, fit to include

further figures, but also a zooming out of an obsessive enhancement of mimetic realism. The Paliotto might be called

reactionary or – modern (a question of perspective), because it could have preserved, for a viewer knowing the Virgin

of the Rocks, the memory of atmospheric realism, but this memory is preserved by a design that itself avoids it,

turning to a more stylized not-, and almost: anti-realism – that still uses the ideas of Leonardo’s style. A style of

the (very recent) past, as one might say, if the date of 1490 is correct.

Our more or less innocent promenade has resulted with finding a beautiful microstory at the wayside, but now we have

arrived at a battlefield. The secular and eternal debate over the Louvre vs. the London version of the Virgin of the

Rocks is such battlefield – and I am going to avoid it, knowing that we would find sanity if delving into it, but also

much insanity, amateurism and dilletantism, by which I mean: reasonable reconstructions of the whole history of this

project do exist, but again and again such reasonable reconstructions are outshadowed by miserable rubbish.

We can avoid all that with a clear conscience, zooming out of that eternal debate, since two other versions of the

Virgin of the Rocks are more important to us anyway (pictures below: Sailko). But how is that and what do we see?

In our last episode I had said that we could also interpret the ›workshop‹ of Leonardo as a sort of ›consortium of

painters‹. Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono especially might have remained close to Leonardo all through their careers as

independant painters, which must have allowed case-by-case cooperation (as for example for another Virgin of the

Rocks version). And apart from that (which is also not exactly the same as being part of one constantly existing and

producing workshop) there might have been a sort of routine practice that we should consider a bit more seriously: if for

example Marco d’Oggiono produced another Salvator Mundi picture (or had his assistant produce one), he might have known

that Leonardo expected to be given a fair share of the earnings, since such picture was produced on the basis of a

cartoon initially (even if copied many times) having being created by Leonardo, who, as one might say, expected to be

compensated as the owner of the copyright (see again introduction above). And this might have been similar as to the

Virgin of the Rocks.

Both, Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono, having contributed probably to the London version of the Virgin, seem to have

produced copies in their own right (see Marani 2005, p. 141f.). And these are the two versions we are looking at (private

collection; Castello Sforzesco).

It is striking that both copies remain faithful to the Paris and not to the London version. But we should not be

mistaken: there are hints that place both copies in the period ›after the London version‹. Below we have the one version

that Pietro C. Marani attributed to Boltraffio. But it seems to me that the figure of the angel has much to do with the

Nancy Salvator Mundi (probably by Giovanni Agostino da Lodi; also below), which would allow to raise the question if

the picture does indeed belong into the period of the Zenale headed consortium of painters around the year of 1511. Since

both, Boltraffio as well as Giovanni Agostino, were being part of that consortium.

And also there are hints that place the Marco version into that period. Because Pietro C. Marani has also proposed that

this version might have been offered to Pope Julius II. Hence: two versions faithful to the original design (displayed in

the Louvre version), but later; and as such objects that raise the question if indeed the ›workshop‹ of Leonardo ›worked‹

as I have decribed it: 1) as a classic workshop with apprentices and assistants being instructed and educated; 2) as a

consortium, realizing case-by-case cooperations; and 3) as a loose group of colleagues and perhaps friends, being bound

also by informal cooperation that included free production after designs by Leonardo, but also the respecting of

copyright owned by Leonardo. Thus the question would be: Did the authors of these two versions share their earnings with

Leonardo? Are the authors indeed Marco and Boltraffio? Did the way these copies were being produced manifest the same way

that was applied as to the Salvator Mundi design? And finally: Did Leonardo see these copies, and did he, perhaps, also

appreciate the nuances of alternative versions? With Boltraffio more stressing the atmosphere of a rocky landscape in

greater heights, perhaps near to a glacier, and also more stressing the being blocked of opening views – by further

rocks. And with Marco stressing less the partly distressing, but rather the soothing views rocky landscapes can offer a

viewer, with large windows, not blocked by further rocks, but opening the view from the rather narrow space of a cave

shelter into the wide heavens?

Two) Rediscovering Bramantino

Bramantino is an artist who can arouse enthusiasm in a modern viewer – but only if he is well presented. Since he appears

to remain little known, one can assume that this is not always the case. Not even one of his most beautiful works, the

Story of Philemon and Baucis (Cologne) seems to be well known, judging from the lack of really good photographs.

But this is a beautiful picture indeed, a picture that tells the story, told by Ovid, in its various (but not all its)

episodes. And certainly this is a picture glorifying landscape, nature, the living outside rather than inside a hut, and

a wide heaven.

It seems to be an early picture, datable around the year of 1500, and it aroused the enthusiasm of Wilhelm Suida, who,

in 1905 and in the footsteps of Giovanni Morelli (who had assembled the production of young Raphael), assembled the

production of young Bramantino, dedicating an enthusiastic description to this particular picture.

If one does read the Ovidian rendering of the partly beautiful, partly rather grim story (the Olympian gods, by

extinguishing the not-hospitable inhabitants of the landscape, also extinguish the relatives of hospitable old couple), one

does realize that Ovid does stress the details of living inside a small hut in poverty, the details of how to be

hospitable under such conditions, and certainly he does not glorify landscape. But he offers hints that there is

landscape, by mentioning a lake, and by having the gods, with Philemon and Baucis, climb a mountain – to see the lack of

hospitality being extinguished.

This is not what Bramantino does, who has the story develop outside the narrow hut that, later is being transformed into

a temple by the gods, and perhaps the most important element of the picture is the wide heaven anyway.

The reason why it makes sense to include this picture here is the common motif in this picture as in the Virgin of the

Rocks: it is the motif of transformation, in its multifolded Ovidian sense, but also, with Leonardo, in its

Christianized sense: divine intervention, by ways of nature, has rock transformed into something fertile and, perhaps,

hospitable. A Christianized idea of transformational processes in nature blends with the Ovidian ways – and the creative

flow of artists serves as the medium that makes such blending possible, being its driving force. We see a picture that

might have been, partly, inspired by Leonardesque landscapes, at least one has suggested such influence; but we also see

a picture that might have worked as an inspiration for Leonardo, in its clever composition, its encompassing of many

angles of a story, and in its gloryfying of light and warmth. It is a counter point to the Virgin of the Rocks, in

that it manifests another aspect of the Renaissance, the taking of inspiration from Antiquity, and it is a counterpoint

in mood and atmosphere, comparable perhaps to a wordly polyphonic piece of music, while the Virgin is rooted in the

polyphony of meditative church spaces, which would remind us that we actually are looking at landscapes of the

imagination, in which meditative interior ones blend with the actual warmth and light of real ones being experienced.

Three) Marco the Modern

Marco d’Oggiono is not exactly the artist who has aroused enthusiasm among Leonardo scholars and worshippers. In fact,

in some cases at least, Marco has rather aroused disgust. And it is true – Marco is rather a simplifier and a

popularizer. Which is exactly what many Leonardo scholars are. Who have a rather worshipping relation with Leonardo and

have to be uplifted by him (while in fact they live on him), remaining blind for what could be observed in Marco, and in

Marco particularly. But what could that be?

I think that Marco must have been aware himself that, as long as he tried to follow Leonardo in his footsteps, that he

could only lose in comparison. He did follow him, partly, resulting with Leonarso scholars often seeing him as a

cross-eyed ›little Leonardo‹. But insofar as Marco also must have realized that, alternatively, he could also simplify

and popularize Leonardo, he comes near of being a modernizer. Because simplification tends to bring out artificiality.

And although I do not believe that Marco strived to bring out artificiality versus Leonardesque realism and faithful

illusionism (that aims at disguising artificiality, including manifest brushwork), in some cases, as in the Saint

Barbara shown above (picture: dguendel) he at least seems to do exactly that. Because this is a picture that could

have be painted by a 20th century surrealist. Again only a bud of modernism. But we find it in Marco, while Leonardo

does represent rather the tradition that 20th century modernism was striving to overcome. In fact Leonardo seems rather

to be worshipped today by people, who, in the 19th century would have been admirers of academicism, because Leonardo is

largely admired for being so realistic, so true to nature (which is only a part of what he is). And this is exactly what

a sterile academicism was admired for by (probably) a majority of people. A picture like the Saint Barbara above

these people would have laughed at. But, again, it would have been admired, in its also somewhat absurd nature (the

statuesque rendering of a Saint within a rather artificial landscape, and above all, the slightly absurd toy model of a

tower, the attribute of the Saint), by the surrealists. And yes, they also would have admired Marco instead of Leonardo,

just for provocation’s sake, but this is not what I want to do here. What interests me are these buds of alternative

aesthetics that we find at the wayside. Alternatives that, in case Leonardo noticed them, must also have aroused questions in

him. Whether to remain faithful to nature, and to represent it in all possible faithfulness, or to turn away from what we

can see and represent visually, turning to what we can only know, imagine, hallucinate or abominate – inventing ways to

visualize all that, instead of faithfully representing something already seen in nature.

Four) Zooming Out II – Spaces Within Spaces

But other artists – in this case we do not know who – also explored how mimetic realism could further be developed, in

this case exploring possibilites that I would call cinematic ones (picture above: mfab.hu).

As in the case of the Paliotto leonardesco discussed above, we see a wide, panoramtic ›shot‹ here in this

picture from the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. And it is in some respect an inversion of the Virgin of the Rocks,

since the rock formation that served as a shelter, can be seen, very prominently and well represented in the background.

This allows to focus on the Virgin and the two children, while becoming aware, or imagining, or recalling, that there are

spaces within the space shown that represent other episodes of a story. Perhaps idyllic ones, but in this case I am

rather reminded of looking at a scenery that also can be the environment of manhunt, and this is exactly what the Flight

to Egypt was a result of. We can imagine hiding places such as caves and catacombs, and of course, our conscience has

amassed all such scenes we have seen in many, many movies. We can enjoy the idyllic here, but idyll is – here – the

reverse of what is not explicitly shown, but, perhaps, with additional figures that often, as here, populate the

backgrounds of Leonardesque landscapes (often hunters, horses and dogs) we can imagine. A Madonna & Child by Solario, for

example, shows a landscape with two people giving a handshake, two people that could be hunters, but one might also think

of Joseph as well as of a local guide, familiar with hiding places or the paths of smuggling (of people). All this is

given space here, a space that is wide, not empty, but also wide enough to give our imagination some space. And all this

is achieved due to the Virgin of the Rocks composition, and due to a reversing of it and by another zooming out,

anticipating cinematic means.

Five) Finally Ovid Again

Wilhelm Suida saw Francesco Melzi as the artist who finished works that Leonardo could not finish himself any longer.

The painting in the Gemäldegalerie of Berlin, depicting the story of Vertumnus and Pomona (another tale, transmitted by

Ovid) might be such a picture. If the Gemäldegalerie Berlin had the painting cleaned and restored we would probably know

more as to the question if this painting might be, on the other hand, the one undoubted autograph painting by Francesco

Melzi. Who is supposed to have signed it (on a rock), with the signature no longer being visible, perhaps due to more

recent varnish covering it. And if a signature indeed would be found, we could also draw the conclusion that this picture

is not by Leonardo, with Melzi having finished it, but by Melzi, who certainly would not have signed a largely autograph

Leonardo as his own work. But perhaps one he did himself (on the basis of a cartoon).

With this picture we come full circle. At least to me it seems that there is a dialogue between this picture and the

Bramantino discussed above. Another painting glorifying nature, its fruits, plants, its hospitality. And another picture

displaying a very smart and very thought out and well balanced composition. As I have already pointed out in the second

episode of this history, an episode dedicated to ›unknown Melzi‹, it is also a picture about disguised identities.

Identities of people. But we may say now that there are also identities of landscapes, disguised identities and manifest

ones. Stone might be grim (another grim Ovidian detail: the possible turning into a stone of a woman refusing to love),

but it is eroded by waters, with fertility of ground being the result. Also this picture can be seen as a reverse of the

Virgin of the Rocks, because here, it is about people being transformed – as to their stance regarding love. This

picture is about Pomona being transformed, not expressivley on a bodily level as Vertumnus, but as to her stance

regarding love, while the bodily transformation of Vertumnus is only alluded to (his transformation into a man again).

In that Leonardo (or Melzi) shows Vertumnus as the old woman, however, the transformation by age that Pomona will have to

face in her life, is also rendered here (and not only alluded to). One might see this in a Christian context, but our own

epoch probably would prefer not to, with the question remaining if there is transformation after death or not, and if

yes, which one. Thus we see another picture that might be inspire meditation – perhaps, if there is such thing – a

secular one. But in the case of this picture, an undoubtedly largely worldly picture of the Renaissance would raise the

question of the boundaries of being secular. Another paradox. And perhaps one Leonardo might have struggled with himself.

Selected Literature:

Wilhelm Suida, Die Jugendwerke des Bartolommeo Suardi, genannt Bramantino, in: Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen

Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses 25 (1905), p. 1-71

Pietro C. Marani, Leonardo. Das Werk des Malers, Munich 2005

Frank Zöllner, »Hintergründe«. Ein Versuch über Leonardos »Landschaften«, in: Lorenz Dittmann / Christoph Wagner /

Dethard von Winterfeld (ed.), Sprachen der Kunst. Festschrift für Klaus Güthlein zum 65. Geburtstag, Worms 2007,

p. 37-46

Further Reading:

To the enthusiasm and passion of Mauro Natale for Bramantino we owe an exhibtion catalogue (2014) as well as the papers

of a symposium dedicated to Bramantino (published in 2017). If the pandemic had allowed it, I would have consulted these,

as well as the dissertation by Katinka Johanning on Landschaftsdarstellungen in der lombardischen Renaissance (Hamburg 2011).

The Bottega of Leonardo da Vinci

The picture of the bottega of Leonardo da Vinci is not as blurred as one might imagine (for details see Seidlitz 1935, p. 530; Marani 1998). We will focus here on the early and middle years (up to 1512), and not on the late years, and one might begin with saying that with Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono we see two figures enter the orbit of Leonardo at the beginning of the 1490s that we believe to know rather well. We also see Salaì enter the orbit, at a very young age, and we have, in addition to that, a couple of names, names of figures that we do not seem to know very well, or not at all (a Giacomo, Giulio Tedesco, Galeazzo). Last but not least we have the Giampietrino problem: Giampietrino enters the scenery, but it is a matter of controversy (as far as this question is debated at all), when, since also Giampietrino is still very young.

It is noteworthy that Marco d’Oggiono, already at the end of the 1480s, seems to have had an own apprentice, and that Marco and Boltraffio did create the Pala Grifi together (a picture today in Berlin; picture above), even before Leonardo began to work at The Last Supper in 1495. Due to the work of Janice Shell and Grazioso Sironi we today do know more about Francesco Galli, also called Francesco Napoletano, who did die in Venice as early as 1501. One might imagine that Galli went to Venice with Leonardo in 1501, and if Galli, during the 1490s, for example might have cooperated with Marco, we would have found an interesting perspective: since, if only one single picture of the Marco group would be associated with Francesco Galli/Francesco Napoletano, we would have a picture with hand option 2, a picture that must have been created before Galli died in 1501. Which would mean that hand option 2 must have existed early, and my theory of the pentimento in version Cook as a mere switching from (preexisting) option 1 to (preexisting) option 2 would be positively proven as well as the theory of the pentimento supposedly showing the creative energy of genius (changing his mind) would be definitively falsified.

Brief: in the 1490s Leonardo mentions once that he had paid ›two masters‹ (probably Marco and Boltraffio) for two years; and once that he had six bocche to feed (probably again Marco, Boltraffio, plus Salaì and some of the unknowns).

Below a rather early Marco picture (according to Janice Shell), the Young Christ Blessing of the Galleria Borghese:

And here is a picture (not the only known picture) by Protasio Crivelli, formerly the apprentice of Marco d’Oggiono (picture by Sailko; the date appears to be 1498; location: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte):

In 1501 (3.4.) Pietro da Novellara informs Isabella d’Este that Leonardo seems to live ›from day to day‹ (see Marani 1998, p. 14). And he has seen Leonardo intervening from time to time in portraits done by two of his garzoni (»fano retrati«). But who are these, and which portraits are these (if this would have been about a Isabella d’Este portrait, Pietro would have noted; and after the Sforza had been expelled, portraits of court ladies and courtiers made no sense)? After having written on the picture of a young woman in the Columbia Museum of Art in one of the last episodes, I would now suggest the following:

Leonardo might have done a portrait of a Sforza court lady in the early Milanese years (and still in the Florentine portrait style), a portrait in terms of a drawing or a cartoon. He might have begun also a painting, but since the Sforza court got expelled and exiled after the French invasion, he might not have finished such portrait. He might instead have used it for the instruction of his garzoni: the Columbia picture might have been the one begun by Leonardo (as he seems to have begun portraits with the face, as later in the Mona Lisa), a picture that he might have had a pupil finish, with him retouching it again, adding some lustre. The picture in a private Russian collection might be a second version that he had a pupil repeat (after the first version and the drawing, respectively the cartoon). The Columbia picture shows much gusto for the grotesque, the second version less so, but still to some degree. Thus we would see pictures that have their origins in the first Milanese period (and even in the early Florentine period), but were actually done later (after 1500). And Leonardo might have had a hand in the Columbia picture whose head with the hair as well as the ornated hair net superbly being modelled into the dark is of exquisite quality (as also a single one pearl is, while other pearls are rather mediocre as also the bust and the modelling of the dress is). We see, as I have attempted to show in episode 13, two pictures that fit into the context of Leonardo’s thinking and doing rather than into the context of Boltraffio’s autonomous work:

In 1504 a Jacopo Tedesco, in 1505 a Lorenzo (di Marcho) enter the orbit of Leonardo.

In around 1505 Fernando Yáñez enters the orbit of Leonardo, helping him with the Battle of Anghiari (as also does Riccio della Porta). Yáñez cannot be the author of the Prado Mona Lisa, if the Louvre Mona Lisa was finished only years later, since the dates (showing that Yáñez was active in Spain after 1506) do not allow to postulate it. In works of Yáñez done in Spain, however, we find echoes of Leonardo’s works (see the example below).

Around 1507 Francesco Melzi becomes a pupil of Leonardo (and also a sort of secretary).

In 1511 (or even earlier) Giampietrino is an autonomous master.

In 1511 Salaì seems to have created a (signed and dated) picture of Christ:

In around 1511 we see Marco, Boltraffio, Giampietrino and – Giovanni Agostino da Lodi in close contact, not only because we have a source indicating exactly that – we also have pictures indicating exactly that, and one of these pictures seems to be even dated (but the ›date‹ – ›XII‹ – is rather referring to the ›age of Christ‹):

The Prado Mona Lisa (below) was probably begun at the time Leonardo also started reworking or completing the Louvre Mona Lisa, probably due to Giuliano de’ Medici wishing so, and hence perhaps in around 1511/12.

In around 1517 Marco d’Oggiono is cooperating with Giovanni Agostino da Lodi (see Shell, p. 173).

***

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

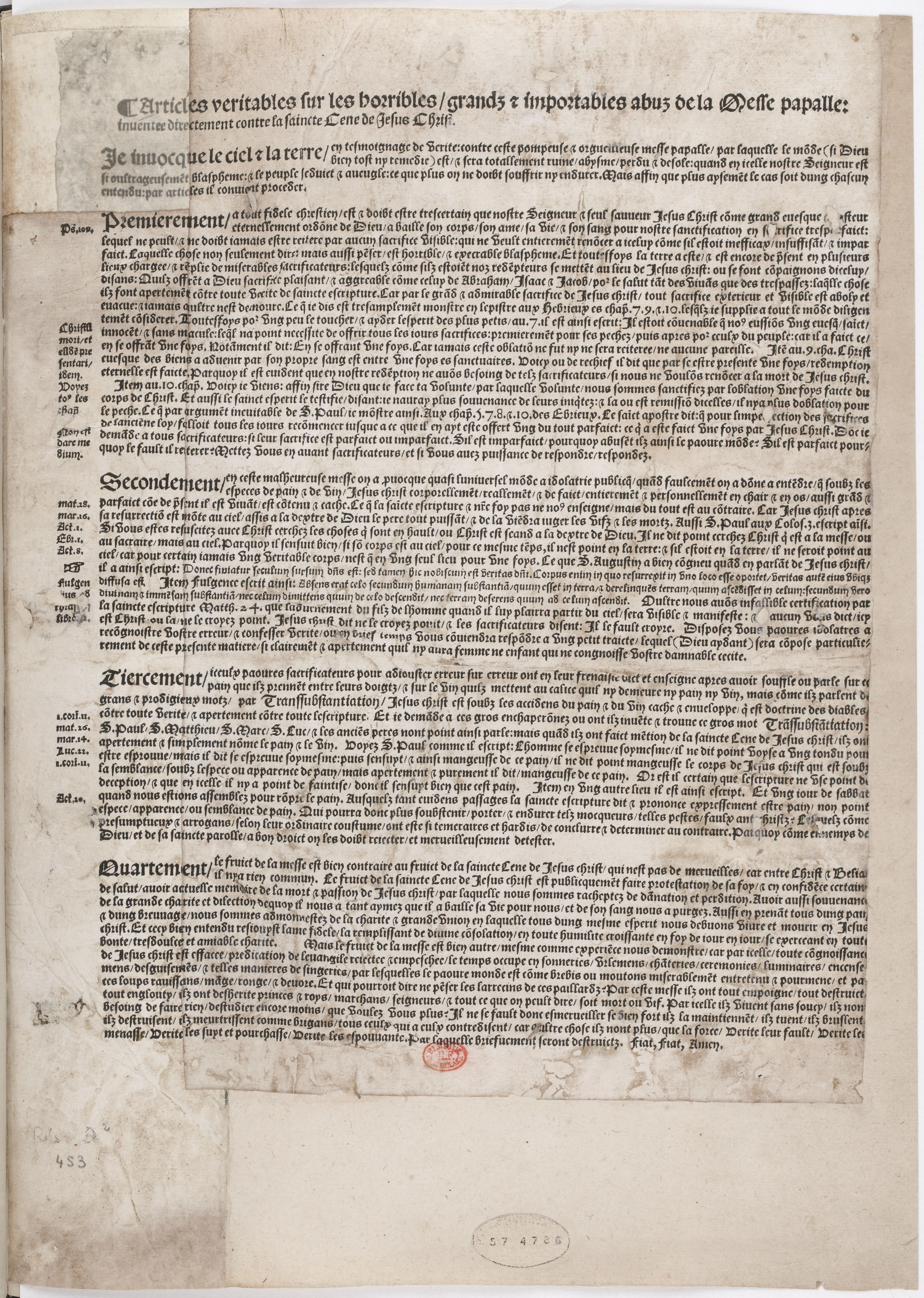

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

Leonardo’s one seminal contribution to landscape painting was the rocky landscape allowing to delve into a meditation on the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. A type of at the same time artificial, meditated and on the other hand very realistic natural environment, rendered also to relate to the experience of narrowness vs. open space (with the ›windows‹ within the rock formations), warmness vs. coldness, high vs. low, dark vs. bright, and so on, and all this condensed within narrow pictorial space. The dogma of the Immaculate Conception, however, was disputed, and pragmatism of artists must have been demanded, if, in some cases, its symbolism was to be rendered or – to be avoided, depending on the wishes of commissioners. Such controversial dogmatism might have resulted with artistic pragmatism, and such might also have led to the landscape of rocks turning into solid architecture. And with Zenale’s spectacular Denver panel (picture above: denverartmuseum.com) we will discuss Leonardeschi & Landscape in the next episode of our New Salvator Mundi History. Below pragmatic Giampietrino, who turned the rock landscape into a house, while keeping a window, opening the view into actual landscape.

See also the episodes 1 to 18 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

A Brief History of Digital Restoring

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS