M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

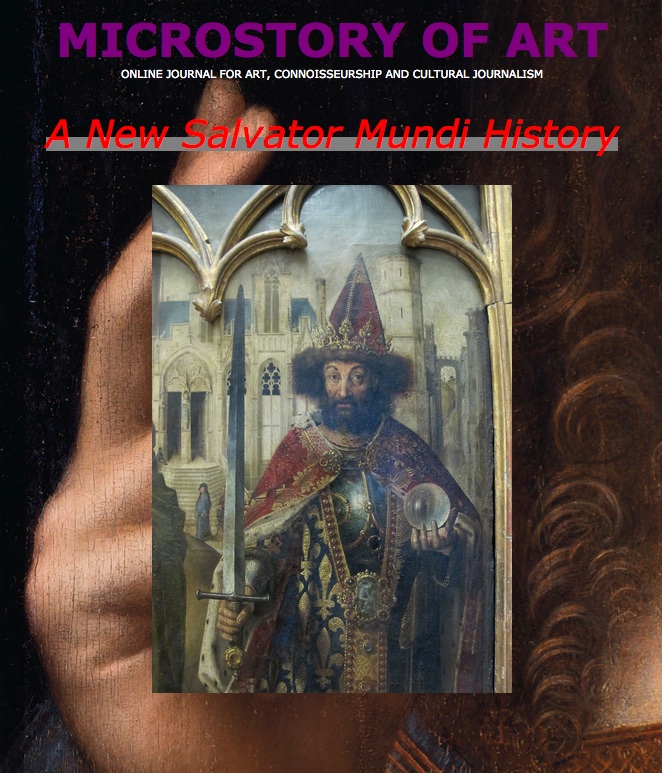

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

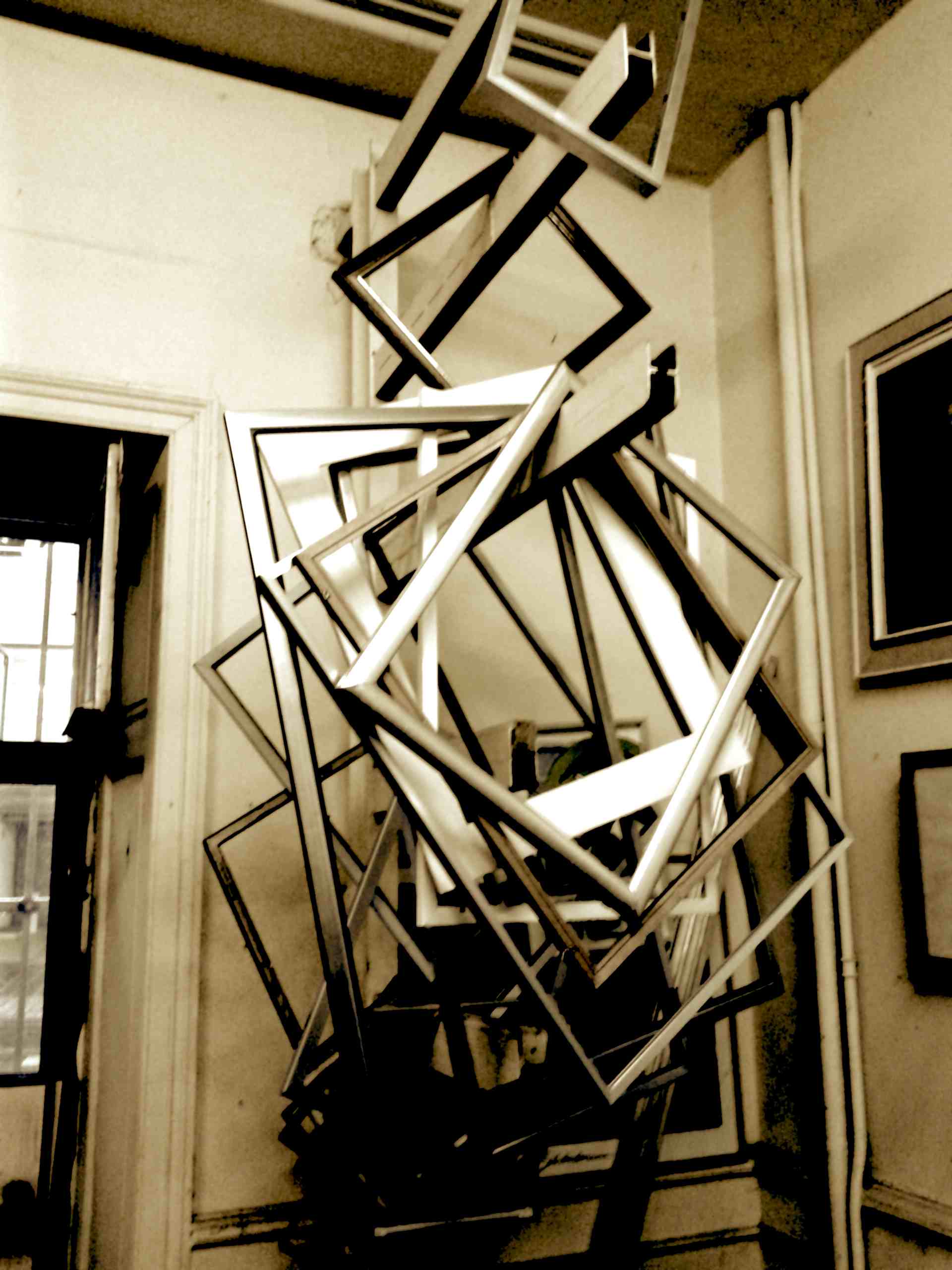

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Iconography of Sustainability  |

One: Conversations with Bruegel

(11.4.2022) If one had asked artist Pieter Bruegel (the elder) what he’d think of the concept of sustainability, he would not have understood at first. But after a short while, after some little conversation, perhaps theatrical, perhaps mockingly funny, he would have said: ›yes, I see – what you mean is in fact what we would call prudentia.‹

The world of Pieter Bruegel, the Christian world, had a different frame of reference for very similar ideas: because – what, in essence, is sustainability? What does this notorious notion essentially mean?

For our purposes here I would say that sustainability means that things, entities, projects and processes have a secured future, due to people caring about things etc. having a secured future.

If we look at the above engraving, not executed but designed by Bruegel, which is called Prudentia, we see, apart from the central allegorical figure of prudentia, people caring for themselves, for their community, to have a secured, or at least a less endangered future: they secure the dyke, care for provisions, and even do care for the Everafter. Which might remind us that sustainability is in fact a more modern and a rather secular term, having, in its narrowest sense, a history that goes back to 18th century forestry, but that it also includes a perspective that goes beyond individual lives, at least in terms of earthly lives, and that the idea of prudentia, the wise prudence, is aiming at exactly this as well: securing a future by anticipating the endangerments of such future, and this only in a wider sense. The Christian frame of reference is one that is wider and more decidedly morally oriented. Speaking of one virtue such as prudentia means speaking of all the seven virtues (and also of corresponding vices and sins). The shown engraving is coming from a series covering virtues and vices. And if one would now explain to Pieter Bruegel that the very notion of sustainability has come into fashion about thirty years ago, which means: around 1992, the year of the Rio Earth Summit, and that this very term, while it does not necessarily refer to the whole globe and its future, is usually meant to refer to exactly this: it is about the global future, the relation between North and South, the relation of economy and ecology, and the vision of perfect, or at least a better harmony in such relations – if one had explained all this to Bruegel, he would perhaps said nothing and silently, perhaps noddingly have pointed to designs meant to cover the sin of hubris. And he would be right: it is, least to say, ambitious, to think about harmonizing literally everything and in a global perspective and vision, that also and decidedly encompasses the dimension of global future of humans on earth and in relation to earth.

Two: In Search of an Iconography of Sustainability

But this is, among other things, what makes it interesting to look for and to study an iconography of sustainability. Thirty years of such iconography, but also, as we have seen, the much longer history of a very essential idea that goes back very far. I don’t know if such iconography, speaking in a wider sense, does even exist today, because I am suspicious that much associated with the idea of sustainability has also to do with illusions. But I am looking for it, for good and interesting examples, and I am aiming also at identifying and naming illusions. I am finding examples that might be interesting to discuss (such as the engraving by Bruegel), but it is essentially about confronting ideas, questions, with examples, and perhaps, as we progress, we might gather insights as to an iconography of sustainability, as to ways to visualize something that seems to be rather an abstract idea, and which turns out to be, after some reflection, as something rather complex in its actual realities. We might muse about the question if an imagery of sustainabilty might refer to utopian ideas more than to actual realities, and if such imagery, beyond visual slogans and icons (perhaps only pretenting the contribution of a coffee mug that has a logo on it to a more sustainable future), is not becoming only interesting if, perhaps, it deals rather with the more subtle, unseen endangerments of things or processes that show in marginal signs rather (that later, after some insights are gathered) might be termed as ›writing on the wall‹ (another Christian reference that we hardly might be able to escape).

We might have to deal with contemporary art in its often very superficial mere illustrating of thoughts, but also with rare exeptions of really impressing and interesting works of art (not necessarily to be termed as ›Environmental art‹) that in some way or other might deal with the idea of sustainability. In Bruegel, by the way, we find very elemental strategies of how one, in artistic, visual terms, might speak of sustainabilty, because Bruegel used the visual strategy of ›contrasting pictures‹, for example in his Alchemist (above), which means that we see an alchemist at work with his work leading to nothing, and in the background the alchemist’s family on its path to poverty. In other words: sustainability might mean: while we are looking for a success story or at a success story, we have to keep in mind what might happen if the story might take another path and if a chosen strategy might actually fail. A substantial iconography of sustainabilty would be based, might be based on more than one image, and perhaps, as here, on contrasting images within images. Brief: while, coming circle, sustainability, in its contemporary understanding (and usually without such awareness) actually envisions a paradise-like state of things in harmony, it is, also in contemporary understanding (and here with more awareness), opposed to the apocalypse. If a global path does fail, then everything fails. It is hard to escape the Christian shaping of our thinking and our concepts. Better: it is useless trying to escape such shaping. It is simply there, and we have to deal with it. A brief look at how articles on sustainabilty are illustrated does show, that opposing images seem to be the first choice, or the palm tree in the rainstorm, as a way to be very brief: the paradise is in danger. And perhaps such iconography is already so common that it is not necessary anymore to spell it out (as Bruegel did). It is already in our heads and minds. But is this a conscient way of dealing with the issue of sustainabilty or rather a lurid one?

Three: A Pictorial Atlas of Sustainability

As a frontispiz of my pictorial ›atlas of sustainabilty‹, of my confronting of images with critical ideas, I would choose a classic example from 14th century Sienese painting. An example that every art student does know, but I am framing it here in a completely different way. It is not about the all too obvious, the effects of good and of bad government on the countryside and on the city, as painted by Lorenzetti. It is about something else: the fresco displaying the effects of the bad government on the countryside (above) is in a rather bad shape. It had been painted on a wall that turned out to be more damp than the wall on which the effects of the good government on the countryside had been painted. And this I see as a metaphor of sustainability, which, beautifully also is associated with political content. But here, deliberately, it is about the material state in the first place: the future of a work of art dealing with sustainable ways to govern depends upon caring for appropriate choices of materials and strategies. One choice turned out to be more sustainable than the other. Accidentally, perhaps fortunately it was the fresco with the effects of the good government on the world around it (below). And the showing of contrasting paths, as we see, was in fashion even earlier than Pieter Bruegel, whom, still I would like to honour as the founding father of a reflected iconography of sustainabilty of the modern age, which, in the 16th century with its credit-based economies of conquest had just begun.

1992 (Learning to See in 1992):

(Picture: DS)

(Picture: DS)

(24.4.2022) I have lived three times through the year of 1992, which was the year of my 21st birthday. The second time was, when, as a doctoral student, I made the ›history wars‹ of the 1990s, and especially the international debates on occasion of the Quincentenary of Christopher Columbus’ first journey (1492-1992), the topic of my doctoral thesis (Geschichtskultur und Konflikt; published in 2005). And the third time was only recently, after deciding to dedicate a visual essay, this essay, to the topic of sustainability. Doing this visual essay means also to take a deep breath – to reflect on what has happened since that pivotal year of 1992.

Thirty years have passed, since I went on that interrail trip across Europe in the summer of 1992. We started with Prague, to turn to Scandinavia via Berlin, and the journey ended, after having reached Portugal, with a return to Switzerland via Paris. I was aware at the time that there was, also in the summer, an Earth Summit taking place at Rio de Janeiro (I still got magazine clippings from that period), and I was observing, also in newspapers and magazines, the Quincentenary, which actually had started on Columbus Day 1991 (12.10).

It was in the wake of the Earth Summit of 1992 that the concept of sustainability got popularized. I am proud to say that one of my first seminar theses was dedicated, in 1993/94 to a critical scrutiny of the concept of ›sustainable development‹. But who would have thought that, thirty years after the Earth Summit, sustainability would be such a buzzword, as it is now (after ordering a replacement for a power adapter recently, I got a confirmation of that order with ›sustainable regards‹). Only in recent years, let’s say: during the past three years, a new concept has emerged: and it is called ›greenwashing‹, and it reflects a growing awareness, that the popularity of the concept of sustainability goes along with an annoying superficiality in terms of how that concept is used (and perhaps misused).

I am studying a more recent newspaper clipping: its header reads ›Sustainability for Dummies‹, it is illustrated with bird’s eye shots of wind turbines in a landscape, and, next to one of the pictures, one reads: ›To live sustainably: everything ought to be in harmony.‹ Yes, it ought to be. But who is entitled of such simplification anyway? Because this is what happened in the wake of the 1992 Earth Summit at Rio de Janeiro. A somewhat abstract concept got simplified to a triadic structure, implying that there could be, ought to be harmony – in terms of harmony between the realms of economy, ecology and – not to forget – society. Again: who is entitled to such simplification? Since such glorious simplification suggests that there is no conflict at all between the aim of ›saving the planet‹ by capitalism, and ›saving the planet from it‹. The seeds of greenwashing had been sown only shortly after the Earth Summit. Because, briefly, the definition of sustainability that goes back to the report of the Brundtland commission of 1987 was probably too complicated, and we got a simplification instead in terms of a harmoniously sounding chord (which by the way, omits what was crucial: the dimension of time; intergenerational fairness; and fairness between North and South).

In 1992, by the way, French composer Olivier Messiaen passed away, and Toru Takemitsu dedicated to Messiaen his celestially beautiful piano piece Rain Tree Sketch II in 1992.

I am not surprised that many cultural trends that could be observed in 1992 are still en vogue. I am not speaking of the music of Michael Nyman here (or, beware, of Toru Takemitsu), but rather of identity politics, of ›cultural wars‹ and of ›political correctness‹. But I am somewhat surprised that, in the context of postcolonialism, the topic of slavery has grown to such prominence in recent years and on such an international scale. In some sense the ›history wars‹ of the 1990s prepared for this (the history of slavery was not unknown in 1992; and any historian not having lost his senses would have been aware of the relations between the conquista, the transatlantic slave trade, and the demographic history of the Americas, not to mention the history of civil rights). But still: it is a little bit surprising how mighty these currents have become only in recent years.

The 1990s also saw the so-called visual (or pictorial) turn of the humanities. But being suspicious of such turns, I’d like to state that, in my impression, especially the so-called Bildwissenschaften have not kept its promises. And one of the reasons to do a visual essay such as this, is the reason that the visual discourse of sustainability, as far as I can see, has not been dealt with. And if it has – it has not been dealt with it critically enough. Hopefully, what I am seeking to do here, might inspire others (this is the general reason to do such things). Perhaps it does also inspire myself, to do more such essays (and perhaps one day one will have to think of an essay on the ›Iconography of greenwashing‹.

(Picture: wikideas1; from section ›unconventional wind turbines‹)

At the time of the so-called ›visual turn‹ I was a student of sociology, history and literature. I turned to the visual arts more decidedly only later. So I am here going back to my roots, and, indirectly, reflecting on the way things turned out. It is, on some level, a synthesis, this undertaking of a visual essay on sustainability. I think that having a pictorial atlas of sustainability would be rewarding, useful, perhaps inspiring. And this is what I am aiming at.

In 2001 Wikipedia got online. In 2022 it is also one the major virtual art museums. Because there is, for example, a section on ›wind turbines in art‹ (and also a section on ›wind turbins in heraldry‹). Who would have thought of that in 1992?

(Picture: Ralf Lotys)

Apocalypse:

(Picture: Andrew Bossi)

(2.-4.5.2022) Wow, it is a beautiful day, and I am going for a short stroll.

To realize that I am living in a jungle of signs. Another Day In Paradise, but there is so much to decipher. Is the sun shining on nothing new? If only we would know – and there is so little guidance.

If we would turn left – we would reach, after a while, a recyling bin for clothes and shoes. It has a postcard shot of the Matterhorn on it, to strenghen the feel of doing something good – by giving your old shoes away.

If we would go straight, we would pass an ad for a local energy supplier. It has the buzzword on it: nachhaltig/sustainable. Is this our first greenwashing-alert of the day? I chose to go right. We already know that ›sustainability‹ has become a buzzword, meaning, in its most superficial sense: whatever is associated with sustainability – it must be something good. It must be ecologically correct, politically correct. Please ask no further questions. But this is exactly what we are going to do here – asking questions, while observing.

The iconography of sustainability, obviously, is deeply intertwined with an iconography of the apocalypse. And how could it be different? If sustainability means to secure a future (for you; for us; for everyone on earth), this undertaking could fail. And this would be the end of it. The end of the world. As we know it. Or in absolute terms.

Being brought up during the late Cold War-period I am familiar with various types of apocalyptic iconographies and songs (like the one by R.E.M. of which I have just quoted). We had Mad Max, to name another example (of which I have only a vague memory; but I do remember the hoarse and low voice of Tina Turner, singing Thunderdome; the song was called We Don’t Need Another Hero).

It seems to me (I seem to remember) that young people did not take the apocalyptic mood of the 1980s very seriously. This was rather something adults did, if they did that at all. The mood, whatever it was, was the normal mood – and nothing happened. Of course Schweizerhalle did happen (and I do remember this rather in acoustic terms as well – the radio, the car with a megaphone; but for us, as kids, it was more about ›do we have to go to school or not‹); the same with Chernobyl, which, at first, was something vague that just had happened in another country.

The age of Bruegel did not only know the apocalyptic mood of the Reformation and the subsequent – many, many – religious wars, but the age of Bruegel also knew the experience that prophecies (of a new deluge during the first decades of the 16th century) had been false. We know so little about Bruegel that we simply do not know, if this experience, in some way or the other, shaped his character. Perhaps something that is familiar to us, was already familiar to Bruegel: one does only act – as a society – if one is forced to act. Individuals might think that wise foresight might be something good, but I dare that a majority of people only moves, if it has to (by which I mean: if, by a democratically elected government, rules are being introduced that apply for all). And, despite all the sustainability-talk, I am rather sceptical as to Homo sapiens turning into a Homo wise foresightiensis right now. A collective mood might be inclined to support sustainability, whatever it might mean. This could be something good, if sustainability is decidely something good. If, yet, it is already and to a large degree mixed up with greenwashing, we do have to ask questions.

The ways Bruegel depicted the apocalypse, by the way, are still very prominent ways. We had Mad Max, and Bruegel had the Dull Gret (on the right), doing her stroll in a landscape of hell. Which means that we have both iconographies available. And of course, on posters the cooling tower of a nuclear power plant is growing out of Bruegel’s Tower of Babel.

Now we have reached another sign, which, however, does confuse me: a local blogger/poet has created a poster, transmitting the message that everyday experiences (›waste‹) should be transformed into literature. A symbolic globe is being thrown into a recycling bin, with the globe having a kind of ring (reminding Saturn), made out of the recycling symbol. This confuses me. But I do understand what is being transmitted here, and the particular use of symbols might just remind us that only a small move away from conventional use is turning symbols of sustainability into symbols of apocalypse.

Only as a student I learned about concepts like the ›society of risks‹ (from the discipline of sociology) or the concept of exponential growth (that, now, during the pandemic, has risen to enormous prominence again). In other words: I had learned that also things not obviously indicating apocalyptic scenarios can still be associated with apocalypse. The Limits of Growth-report (which, as to the German paperback edition, had a drastic cover – but Bruegel had been more drastic; see on the left and on the right) had worked also with the example of the water lily – to illustrate the concept of exponential growth. A pond might be covered – rather suddenly – with lilies suffocating the pond, and ›rather suddenly‹, because the pace, the dynamic of exponential growth is systematically underestimated by humans. If water lilies in fact do reproduce in such way – I am not a botanist, and I do not know for sure. But it seems to me that a large, large majority of pictures, the picture that I do find to illustrate the growth of water lilies, are rather meant to highlight the beauty of water lilies, and not the concept of exponential growth, and thus, the danger that might be arising from something seemingly beautiful.

(Picture: br.de)

(Picture: Patrice Icard)

(Picture: Celeda)

Banality (vs. complexity):

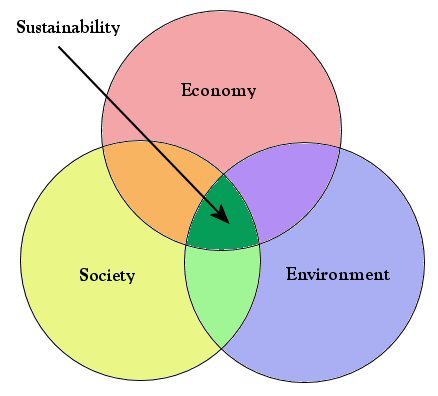

(Picture: Sustainability Hub)

(8.5.2022) What is kitsch? Kitsch is the pathetic failure, given a very, very high ambition. If you would ask me, for example, what I think to be the meaning of life – and if I would answer: 27 – this would not be kitsch, because it is (perhaps) funny (if stolen). It is not kitsch, because I would be rejecting the very, very high ambition ironically. But if I would try seriously to give a serious and meaningful general answer to that question (accepting the very, very high ambition) I would probably pathetically fail – producing (intellectual) kitsch.

If you would ask me, what, in essence, is sustainability, and my answer would be – seriously – that ›everything (economy, ecology, society, various societies) ought to be in harmony‹, then, beyond reasonable doubt, one might accuse me of producing intellectual kitsch. And the discourse, the iconography of sustainability, beyond reasonable doubt, is full of it. The question is rather: do we have an eye for it? Are we able to make a distinction? And again: the definition of kitsch, my definition, is the pathetic failure, given a very high – and serious – ambition.

The above diagram is not kitsch, but it is obviously banal. Let’s put it that way: if the above diagram would be a work of art, I would subsume it into the category of YO-art. What is that? This is my abbreviation for: Yes, okay – what else do you got? Because the diagram is too banal; it is not really worth to dedicate too much time to it.

The above diagram is not kitsch, in my view, because the intellectual ambition it is reflecting is probably not very high. And it is also not pathetically failing. It is just a lame simplification, an attempt that does not serve any serious purpose. If, however, such diagram would be presented as the essence of sustainability, one might refer to it as intellectual kitsch, since this would be a pathetic failure – given a very, very high and serious intellectual ambition.

Complexity (and the problem of abstraction):

(Picture: gaeanautes)

(6.5.2022) In the writings of economist Herman Daly, a key thinker as to environmental economics, we find few illustrations. A few diagrams, however, that seem to have been eye openers for some people (the empty earth vs. the full earth diagram, for example). – I am reading the Daly biography by Peter A. Victor (published in 2022), and why? Because in my 1993/94 seminary thesis on the concept of ›sustainable development‹ I had been drawing from the writings of Herman Daly. I had read, then, about the concept of a ›steady-state economy‹ and had become a little familiar, although, later, I moved away from economy and sociology, with the economic discourse of sustainable development, with the debate about growth vs. degrowth, and with a style of scholarship that can only be referred to as being rather abstract.

Now, roughly thirty years later (while I may be the only reader of the beforementioned biography who’s interested in the visual dimension of the economics of sustainability) it seems to me that the discussion is more or less at the point it was in 1993/94. I am saying that as a layman that might be a little more informed than a layman who has never been in touch with economic discourse at all, but still – this is my impression as a layman. Patterns of consumption that cannot be generalized seem as unethical to me today, as they seemed unethical to me in 1993/94. Has there been so little intellectual progress in roughly thirty years?

Be it as it may – but it may also be that, in recent years, we have seen more changes on a rather superficial level, and this, also might have had to do with the problem of complexity, as well as with the problem of how to transmit complex subject matters to a large audience. Above we have seen the banal dimension of an iconography of sustainability. Here we might be confronted with a more complex and demanding level of discourse. But it seems to me, thinking of the success story of the concept of the ecological footprint (also, in some way or other, related to the work of Daly), that more could be done to convincingly visualize complexity. The management rules of sustainability, for example, might be something that, if we think of the popularity of the ecological footprint concept, would deserve to be visualized convincingly as well. And this is a task that – informed – graphic designers might have to fullfill. In case that graphic design, however, enters the service of greenwashing, we will get more of impressive, suggestive superficial visualizations of alleged sustainability (which is, by now, lurking almost everywhere). But there has to be done more, to visually guide people. To help them to become observers. Decisive clues, in case such clues can be observed in reality (given than one is being informed), can be named. And things that are named, can be seen. Also by others. Diagrams suffer the fate of being seen and not being seen. Diagrams have entered the arts, if we think of painter Cy Twombly, for example, but what Twombly did, was to work and to play with the suggestive dimension of diagrams. What we are waiting for is more intelligent visualization of discourses that are very abstract, but still have to be transmitted to a large audience, since they are important. The concept of the ecological footprint has reached a large audience. At the same time much banality has reached a large audience as well. And this seems to be a problem that has to be dealt with.

Earth Summit:

(Picture: Bibliothek am Guisanplatz)

Apparently some 17000 delegates and some 8500 media representatives had attended the Earth Summit at Rio de Janeiro in 1992. A lot of folks, as one might say!

The historiography, however, covering this particular event, does not yet seem to be equally rich, as far as a variety of perspectives is concerned.

I have not found ›the one reference book‹ covering the Earth Summit of 1992 in all its aspects, but at least I have found a variety of perspectives; and I have decided to recommend four particular books, that, each in its way, do transmit something about this particular event:

– Swiss-activist Bruno Manser (on the left) had attended the Earth Summit as well, and the Manser-biography by Ruedi Suter (Bruno Manser. The Stimme des Waldes, Oberhofen am Thunersee 2005, p. 204ff.), has a sensitive and well-informed account of Manser in 1992, which includes the information that Manser, within a group of paragliders, paraglided, in tandem, from Corcovado hill.

– Choy Yee Keong, Global Environmental Sustainability, Amsterdam 2021, offers a rather affirmative perspective on the United Nation’s Journey toward Sustainable Development and puts the event in historical context in terms of including accurate chronologies.

– Which should be read together with Joachim Radkau, Die Ära der Ökologie. Eine Weltgeschichte, Munich 2011 (the perspective, here, is decidely more critical).

– And finally a book with some very critical remarks: Eugene Linden, Fire and Flood. A People’s History of Climate Change, from 1979 to the Present (New York 2022). From which I learn that »energy was dropped as a separate section in the Rio Earth Summit of 1992« (p. 105). Linden concludes (same page): »The conveners decided that they didn’t need a separate section on energy solutions at a conference whose primary focus was climate change and development.«

Footprint (ecological):

(8.5.2022) If we think the whole of the iconography of sustainability to be art, we may make a distinction between ›abstract‹ and ›figurative‹ art. A traditional distinction that we are transposing here, from the discourse of art to the discourse of sustainability. We have abstract art, because we have diagrams, complex ones and rather simple, if not banal ones. We have figurative art, we have metaphors. Like the ecological footprint. And we even may speak of conceptual art, if invisibility is made visible, by abstract or figurative means.

The discourse of the ecological footprint is interesting in several ways. It may be called the success story in terms of visually transmitting the problem of sustainability. Graphic designers seem to love it, to play with it. And yet it is not something banal, since the concept is based on serious reflection. Thus, what we are observing, in observing the iconography of the ecological footprint, is actually a chain of translations. Abstract concepts have been translated into a metaphor. And with this metaphor graphic designers love to work, adapting it for specific purposes. These processes deserve to be observed more closely (which may happen later). For the moment it may be enough to state that there seem to be success stories within the iconography of sustainability. And the broad perception of the ecological footprint concept might be one of them.

Goals:

(Picture: un.org; author unknown)

Hand (protective hand):

(9.5.2022) A Christian Allegory by Flemish painter Jan Provoost. And this is the hand of God that we are seeing here, holding a globus cruciger on its palm.

The many (pair of) hands that we are seeing today – holding and protecting alternatively a tree, a plant, or, as here: the whole globe on its palm(s), demonstrating a will to thoughfully, mindfully protect, to care for what is, at the same time, presented on its palm – might be seen, again, as faint echos of an iconography that is coming from far. Is man made after the image of God? Perhaps. But it was also a hand, probably the hand of a smoker, that did hold the package of cigarettes, the package that, afterwards was thrown into the basin that does water a local pond nearby. It even seemed to have the recycling symbol on it, the package. In the basin. But, at closer inspection, what had seemed to be a recycling symbol, had only been the advice to quit smoking. To throw the package away. By hand. But into a bin.

The eye of God has vanished, the hand has remained. But it is the hand of humans.

Invisibility:

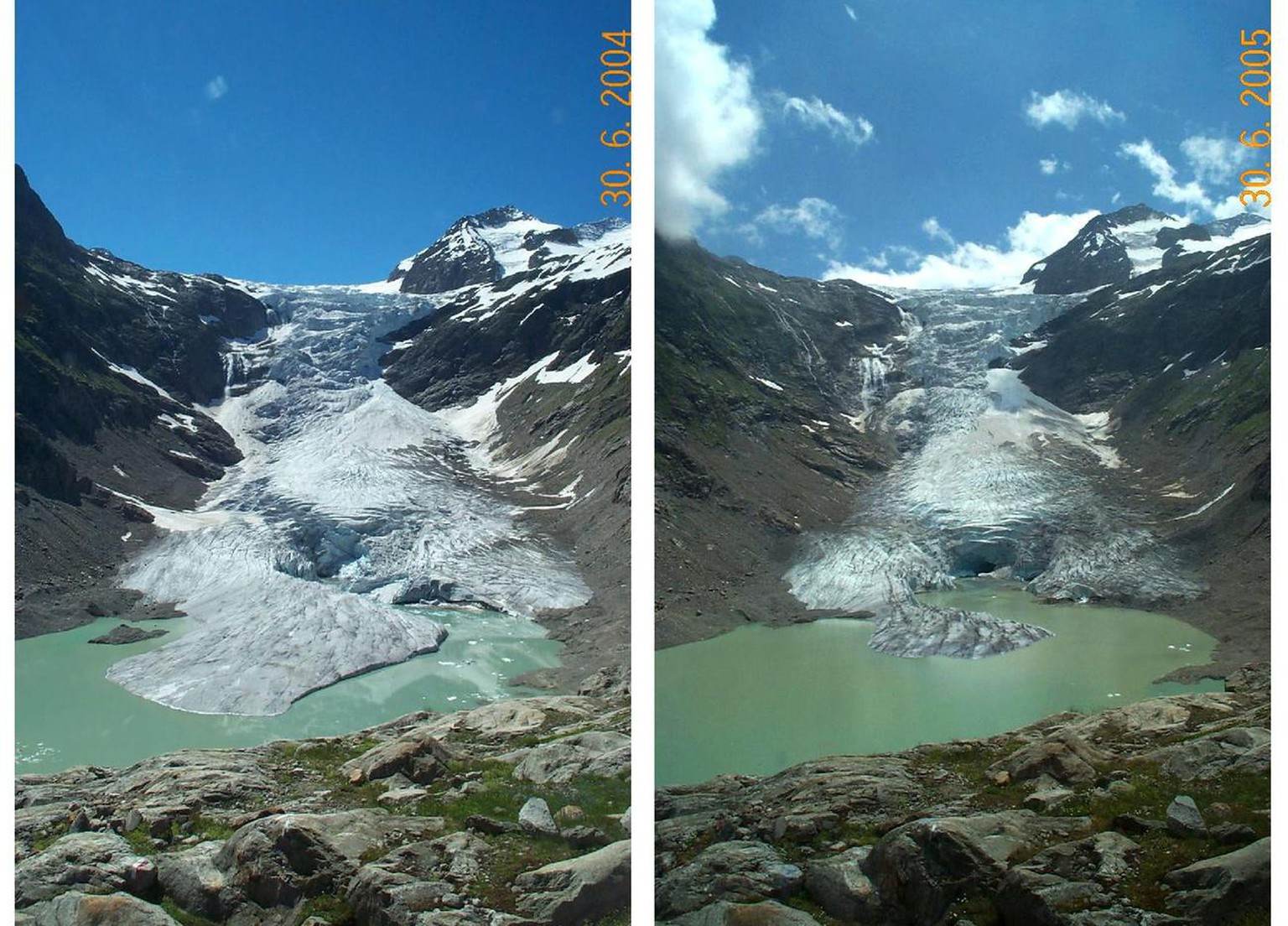

(Picture: VAW ETH ZUERICH ; Triftgletscher)

(1.5.2022) This is a paradox, but it is one gist of the matter: the matter is an iconography of sustainability, and sustainability is not necessarily seen, not necessarily visible. It might even remain invisible all the time, given that changes towards unstainable states (in systems) are not being noticed, not being watched and observed. How can one notice such changes? For example by way of time lapse sequences (see also: Recycling). And here are some examples (from a report on ›6 places where climate change can clearly be seen‹. Glaciers melting might be the one classic example, next to corals bleaching. If two images are juxtaposed, with the second image highlighting such changes and showing clues of unsustainable states having been reached or coming closer, one can conclude that the first image is representing something closer to normal (invisibility of sustainabiliy, but sustainability that can be made visible and graspable). So it is made visible here that one challenge of an iconography of sustainability may be, that it is about making things visible. But explanations remain always necessary. And representation of any king is always tricky. It has to be observed as well. Because it is not something natural but artifical. Something created by humans, just as the concept of sustainability is.

Observing the observing (picture: EPA/AAP/XL CATLIN SEAVIEW SURVEY)

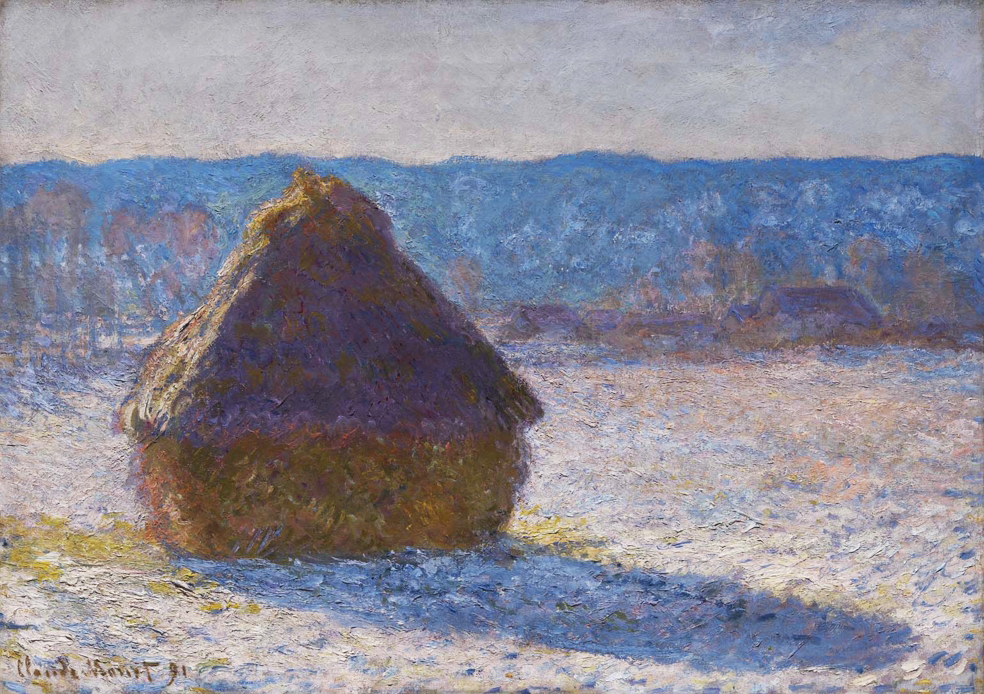

Monet:

(6.5.2022) Why reproducing some of the greatest hits of Impressionism here? Well, because French painter Claude Monet does belong into a gallery of sustainability. And this at least for two reasons:

First of all: his Haystacks, which are not haystacks, but Wheatstacks (covered with hay), may depict something that could be referred to as an unspectacular subject, being only interesting for it being seen in various lights (of summer, of winter). But why are these ›stacks‹ still there in winter? Was it because the painter wanted them to be there (he cared to have an oak arranged without leafs, to get a ›oak in winter‹ effect)?

No, these stacks are still there in winter, because they represent the traditional storage method, used by peasants at the time: wheat was harvested, then dried (in stacks, covered with hay), and threshed only, when the threshing machines came by (which could happen as late as in the next spring). So what we see, is actually good householding. Caring for future provisions. Providing for bread (in the next year). Although, of course, it is possible to focus on the change of colors and light in these pictures only.

The second reason for including Claude Monet here, has to do with the effort necessary to give us his apotheosis of Water Lilies. As mentioned above, water lilies have to be looked after, and the general effort necessary to have Monet’s garden at Giverny arranged the way Monet wanted it to be arranged, was huge. There were several gardeners, there were several crises (inundation; storm), not to mention the initial crisis, having to do with the fact that the local people did not want water lilies imported into their neighborhood. So what we see in Monet’s pictures is also the result of staging nature. And if we think of the effort necessary to stage it, we may become aware that sustainability is seen in these pictures, but as the result of an effort, not necessarily thought of or visualized.

Picture: Marion Schneider & Christoph Aistleitner)

Palm tree:

(1.5.2022) Is it Eurocentric to know of Joseph Beuys’ 7000 Oaks project, to know even the details (including the ways it was financed: by endorsing a Japanese Whiskey, among other things; and also by Andy Warhol contributed a sum) – while not knowing that Beuys had planted, in 1980, also two palm trees (one being a rare Lodoicea, also known as coco de mer) on the island of Praslin? Or was such act Eurocentric? (Not to mention the ecological footprint of such artistic endeavor.) One can read about the act in the Beuys biography of HP Riegel (see p. 457), and on the same page we learn also about the apparently relatively superficial ecological awareness of Beuys, and the ecological footprint of him as an artist (he loved to drive luxurious limousines). But such acts, the oak project especially, were meant to be a message to the future. They were meant to express the message that someone, at the time, did care (for the future), which, as we have seen above, is one definition of sustainability. Still the historical perspective is necessary. And in hindsight we become aware that the concept of an ecological footprint is relatively new. And it is also relatively recent that art critics and curators as well as artists do care about the sustainability of their own endeavors.

ps: the Lodoicea is named after King Louis XV of France.

Further reading:

(Picture: amazon.com)

Paradise:

(1.5.2022) Oh, it seems that I do get to write on the Bible and Ovid (myth of the Golden Age: Aurea prima satast aetas…). But no, I do get to write on Naked and Afraid. This reality series is so interesting. And it does pose a big challenge to the cultural studies. So, obviously, it is a must.

Why writing on Naked and Afraid here? Because the series, with each and every episode, also does highlight the subject of sustainability. Perhaps not obviously so, but it does. And the challenge is huge, as the participants, a man and a women, naked, are bound to sustain themselves for 21 days with very few items at first, and at a place that, for a viewer, might look like paradise, but usually for the participants, sooner or later rather does look like hell. In other words: the place is usually much stronger than the participants are, at first, and the series is about sustainability in terms of the two participants, an Adam and an Eve, having to create a sustainable existence for 21 days. So it is about sustainability in terms of securing a future for themselves and not for the environment that they are in, but with the environment that they are in. And all the bigger issues, sooner or later, come in: what about killing animals (in case one can be found at all; and in one episode the snake they found, in the end got overcooked)? What about the shame of killing animals for the purpose of human survival (and finally: entertainment)? And what about the goals of such living, and of human life in general? Because in a less obvious way the concept of sustainability comes in, in terms of the expectations the two participants have: most of them come with the goal of surviving, which means more or less: to reach day 21, and to get to the so-called ›extraction point‹, where they may, as successful competitors, leave the challenge, their paradise or their hell. But some come with the goal of ›thriving‹. Some come with the innocent wish ›also to have fun‹. And in a distorted way perhaps – but human ways of living depict themselves drastically and in very elementary crashes of concepts, characters and challenges here. The goal of ›thriving‹, obviously, is hardly ever reached. But in one episode it was to some degree: because the two participants did so well, so that they were able to produce even a little tv-show of their own. And it was not about the problem of how to cook the one snake, but about the problem of finding one, since the man, a Green-Beret-officer, thought that his fellow Green Berets would expect him to eat one (as they think of themselves as Snake Eaters). On some level, life did punish him for that, since at the end of the episode it did turn out that he, as one the most successful competitor of all times, still had contracted something like dengue fever, so that the narrative of this one episode could also be decribed as ›crime and punishment‹.

The paradise myth, which might also be equalled with the idea of living, innocently and without much awareness, in harmony with nature, is thus rewritten, with each and every episode here: and man/woman have to leave. Perhaps more mature (apparently in several cases). But also the Bible tells a tale of man/woman leaving paradise more ›aware‹ (or, if you like, ›woke‹). Only they have to leave, and there is agriculture, laborious work, to wait for them as punishment (and as a consequence farm animals get to be enslaved by men). What happens in Naked and Afraid is, that, in the context of a game show, two participants take the challenge of going (back) to a perhaps paradise-like setting, with some of them being vegetarians (but not necessarily ending up as such), to experience something that, in its outcome, depends on a variety of factors. With the weather only being one of those factors. Because strategies come in, very often colliding, and thus ideas. In one episode one competitor managed to produce a wooden bench to sit on. And yes, thinking comes in to become also part of the narrative itself, since every episode, to some level, depicts also a discourse between Adam and Eve. About how to survive, technically, but also according to what philosophy (spending as little energy as possible by lying around, or by being as active as possible), and to what end (in terms of what there is to transmit to a future life in civilisation).

What, perhaps, is most remarkable about Naked and Afraid is something that has much to do with philosophical ethics and the dilemmata of human existence. It is what one might call the culture of shame. And this is not the shame for being naked, but the shame of having just killed an animal for the purpose of human survival (and, in the end, commercial entertainment, and perhaps, learning). Because there is a whole culture of how to say sorry to the animal just having ›given his life‹, of how to ask for forgiveness and of how to be grateful to the animal just having given his life. I would subsume all this into a culture of shame. There is a discourse within the series and among the participants, but the problem discussed is also the problem of the series itself, which is, at the same time and drastically, highlighting this problem of human civilisation and history: How to deal with that – that humans have killed and still are killing animals for the purpose of their own survival (or ›thriving‹)? There is no anwer to that question yet, only cultural ways of dealing with it. And some are displayed, honestly or not, within that series, as well as by it.

In one episode ›Eve‹ managed to find water apples for her ›Adam‹

which helped to successfully end the challenge

(picture: Forest & Kim Starr)

Proverbs:

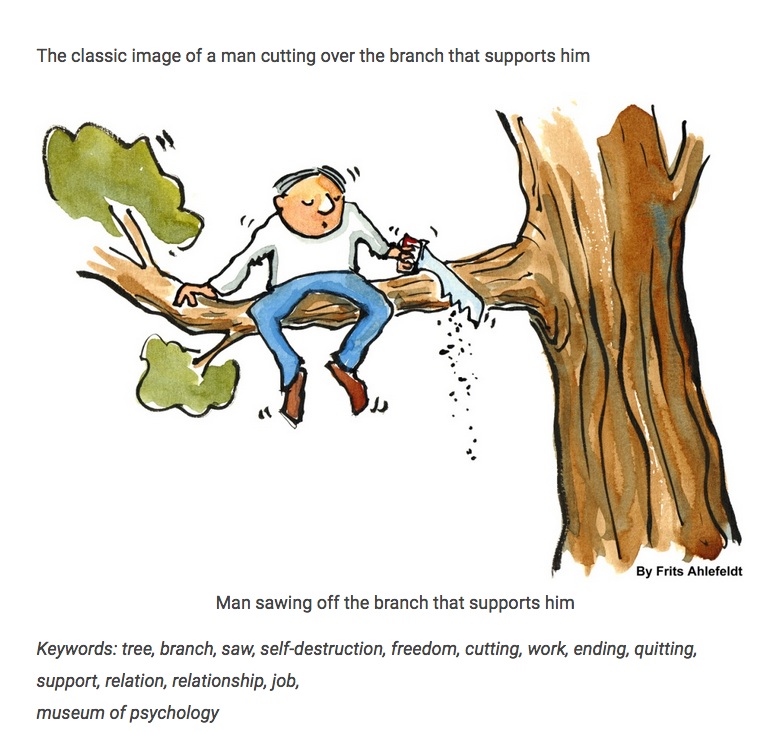

(Picture: museumofpsychology.org ; Frits Ahlefeldt)

The classic notion of sustainability, as one might say, the classic notion as it was developed by 18th century European forestry, is about resource management (as it is about living on wood growing back, without undermining the possibility that it might grow back). But there would have been other paths to develop such notion, since at least one of the proverbs Pieter Bruegel apparently covered in his Netherlandish Proverbs is dealing with another area of rural life, but about the very same idea: and this is the proverb ›shear them but do not skin them‹ (example on the left).

As you might expect from Bruegel this is, since it is dealing with a living animal, the sheep, slightly more aggressive and direct (perhaps one might say also: bloody).

If we are seeking abstraction from that very real idea of shearing sheeps or cutting trees, perhaps surprisingly, we still find a proverb dealing with wood: and this is the proverb ›sawing off the branch on which you are sitting‹, which might be regarded as the more abstract (ex negativo) expression of what sustainability means (with the branch representing a capital stock of whatever kind that ought not to be touched or undermined, since it is existential).

It seems that Bruegel did not cover this proverb, although it also seems that this proverb was widely known, probably since the Early Modern period. It is known, for example, from one Hodja Nasreddin story which I have checked, and which is interesting in its absurdity, and also: aggressiveness (a passer-by is alarming Hodja Nasreddin that we would fall down due to sawing off the branch on which he is sitting, which also does happen; and after which Hodja Nasreddin – perhaps sarcastically, perhaps not – is regarding the passer-by as a prophet, asking him for the date of his, Hodja Nasreddin’s death). Visual representations of this proverb do exist, although, seemingly, not in very great number (and the link to folk traditions such as the Hoja Nasredding tradition, in the present age, is usually lost). Some monuments, being spread across the globe, and bearing testimony to a general popular wisdom of the present age, do exist as well (see here).

Further reading: Hannjost Lixfeld, Ast absägen [›Sawing off branch‹], in: Kurt Ranke et al. (ed.), Enzyklopädie des Märchens, vol. 1, Berlin/New York 1977, columns 912-916

Recycling (time lapse):

(25.4.2022) The plane of a gunrunner has been forced to land. The scenery is Africa (South Africa stands in for western Africa), and in a time lapse sequence of 25 seconds length it is shown, how the plane is almost completely dismantled by local people overnight. The sequence is from the movie Lord of War, and one may wonder if this sequence might be called to be implicitly racist; but I do think that it is not, because in the context of the film it is made clear that the gunrunner (the Nicholas Cage character) is willing to have the plane dismantled by local people. A piece of evidence, one might say, the plane, is made to disappear. And this is what he wants. The locals are just implicitly or explicitly invited to – well – recyle the plane. Which seems to be what they do (on the level of the movie). Because this is also about recycling, about almost, but not wholly completely dismantling and – implicitly – recyling a whole plane. The sequence might be called spectacular, and one may wonder how this was done. Well, the audio commentary by the director of the movie tells us that this is a computergenerated sequence, done by VFX Supervisor Yann Blondel. Thus the landscape might be real (the time lapse of nightfall and dawning perhaps is not), and the dismantling was artificially done. It is not real, but still spectacular imagery of recyling. That may serve to raise questions as to an iconography of recycling as well: does it work (in the real world)? By whom it is done? To what purpose? To what effect? To what cost? A plane skeleton is remaining in the end. Perhaps reminding us that sustainability might not be something absolute, but rather something gradual. The plane that is seen in the movie was a real one. It crashed some time after it had been used for the movie.

Simplicity (vs. banality):

(10.5.2022) The recycling symbol works fabulously. It is fabulous, but one must not forget that not every circular process may be positive. Circularity characterizes, without any question, many intellectual processes, especially within the academe. I have referred to my impression that also the discourse on sustainability seems largely circular to me. Various camps are repeating, again and again, their arguments for, respectively against the fetish of growth. The concept of sustainability seems also much more popular than the perhaps more reflected and substantial concept of a steady-state economy (respectively the concept of ›sustainable growth). Banality is resulting from simplification. How fabulous a circular economy would be. How fabulous the various concepts of disconnecting growth from its – for now – persisting negative effects. How fabulous, if recycling has become so popular and the recyling symbol works as an emoticon. But the bigger picture is remaining the crucial one. And in the bigger picture we might see that a popularity of recyling symbols goes along with circularity in intellectual discourse. How fabulous, if there is no waste. But maybe there has to be some – on intellectual level at least. And if not – at least there should be more of an awareness that not everything becomes fabulous by using fabulous symbols.

Stamp:

(Design of stamp: Florian Pfeffer;

picture: bundesfinanzministerium.de)

(9.5.2022) Once upon a time it was a noble and intelligent hobby to collect stamps. It was a way to get to know the iconographies of the whole world. Many works of art I have seen – for the first time and in small, but handy reproduction – on stamps.

I don’t know if these days are over, or if children still do collect stamps. The stamps I once collected may count among the Old Masters of stamps now. And of course the iconography of stamps was rather Old-Masters-oriented than it was contemporary-art-oriented. A classic is never a compromise; or: if a compromise at all, then do at least choose a classic.

I don’t know if it was the period of the 1990s which calibrated the visual arts, largely and generally, to the level of shallow Pop radio; with instinctive consumers, rather than thinking human beings implied as viewers (and viewing often focussed at viewing the money, the glamour). The stamp shown here – I am afraid that, with the best of my intentions, I am not able to say much good on it – seems to be the attempt of someone trying to produce Pop radio, but the attempt of someone who does not listen to (intelligent) Pop radio himself. Good intention does not make good art. Good intention may make good graphic design, but people do feel, if a demonstration of good will remains rather shallow – because it is forced (and probably a compromise). What we do see here is the forced optimism of someone inviting to a party to save the planet. If kids at school are presented with such invitation, they might feel the shallowness and react with a rebellious and furious We’re in the Army Now-dance. Please stop this ›It’s such great fun to save the world together‹-Pop radio. It is so shallow. Thank you.

Sustainable/Unsustainable Art (and value):

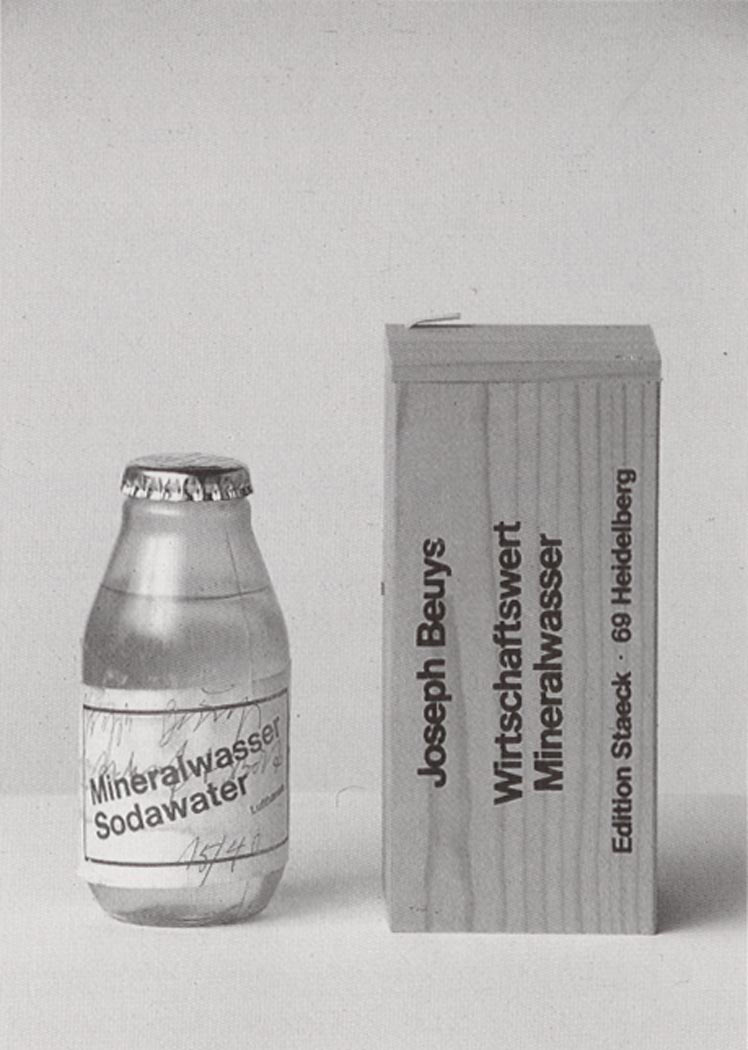

For this we hear Andy Warhol, commenting on a work of art by Joseph Beuys:

»We had breakfast with Joseph Beuys, he insisted I come to his house and see his studio and the way he lives and have tea and cake, it was really nice. He gave me a work of art which was two bottles of effervescent water which ended up exploding in my suitcase and damaging everything I have, so I can’t open the box now, because I don’t know if it’s a work of art anymore or just broken bottles. So if he comes to New York I’ve got to get him to come sign the box because it’s just a real muck.« (The Andy Warhol Diaries, p. 449; 8.3.1981—Düsseldorf)

ps: the work of art seems to have been a variant of Wirtschaftswert Mineralwasser, which can be seen at The Broad, Los Angeles (see here).

(Picture: thebroad.com)

Velázquez and Sustainability:

(8.5.2022) The The Waterseller of Seville by Diego Velázquez is a painting to inspire thoughts on sustainability. I am not saying that it is on sustainabiliy. But it is a painting that implies much and requires a viewer, a reader ready to fill in the space that Velázquez left him to fill in. Of course art historians are, largely, neither able nor willing to do such things, but this is not our problem (one might say, this one quibble may be allowed, that they are, largely, not ›inspirable‹). But what if a painting (like here) requires someone ›to work with‹ the painting, for the painting to make sense?

But back to our painting: an encounter between youth and old age is staged here. One might even speak of three generations being depicted, but the third person in the background, which is drinking, cannot be clearly identified as representing a ›middle‹ generation. What do we see? Water is passed from old age to youth, but the boy, who appears to digest something, something that might have been said to him, a wisdom that might have been passed to him, while he is not quite ready to digest such wisdom. And the important thing is that the boy is not yet drinking, as there is still a bond between old age and youth, since two hands stick to the glass. No eye contact is being made. But we, as viewers are directly looking at the person drinking.

What has to be filled in here, is the meaning that can be given to water (as an near synonym for life perhaps), as well as the meaning of passing something of that substance from old age to youth. It is not far-fetched at all, to think that the wisdom that has just been passed to the boy is vanity, and it is not far-fetched to think that the meaning of vanity cannot be grasped by a young boy (Velázquez, by the way, was still quite young when painting all this).

For a contemporary viewer it must have been quite clear that the waterseller was close to his death, but it is him who still passes the precious substance to the next generation(s). Vanity is to be thought next to youth. And water will be passed in the future (as long as there is a future). The boy will be drinking, the boy will live, but there will always be vanity next to youth. And if something is meant to be sustainable at all – it is this chain. The passing of life from one generation to the next, the passing of wisdom perhaps (because the passing may happen without anyone being aware of it – this would mean that life is without awareness of itself).

The painting is not without awareness of itself. The painting does know that a viewer has to meditate on the meaning of water, on the meaning of confronting old age with youth and so one. The painting does appeal to the viewer to do so. And if a viewer does not, there will be looking without any understanding (which, another quibble might be allowed) is not even consuming.

(I Was Meant to See This, Here and Now… (picture: DS; 9.5.2022 …it had to stop at a red light…)

Writing on the Wall:

(10.5.2022) The writing-on-the-wall-motif, as one could say, is about the instinctive feel, that there may be something threatening coming. It is about fear (growing out of a feel of crisis that is already there), but also, on a more abstract level, about the problem to decipher and to understand the writing, as well as about the problem to handle it, as far as the content of the message is concerned. Insofar the Biblical motif is probably a key motif of, as well as for our time, and certainly a key motif within the iconography of sustainability.

Thus we have assembled the kitsch here – by which I am not referring to the above painting, which is interesting in the way it stages the motif within a very wide space and places the message high above the court and the feast –, and we have assembled the essential core motifs that help us to deal with – well – our situation. One may, as we have seen, react with an invitation to a party, because Erde nur geborgt, and because everything can be solved by a coming-together-dance; but one may also analyse a state of things more seriously. And this also by using the traditional motifs, not without questioning them. The above painting, as suggestively dramatic it may seem, may also be used as a tool to help us naming the crucial problems and questions. Which are: how to read the signs, how to see them at all, how to decipher them – and how to act (if necessary).

Writing on the Wall II (Miami – Venice – Atlantis):

(28.4.2022) I have only visited Venice once and when still being a child, and I am not too keen to change anything about that. I have no problem, due to that one early visit, to imagine Venice as an exuberant half-oriental medieval city. And I have no problem at all to imagine it as a new Atlantis. Which is not to say that I would wish it to go down – certainly not. What I am saying is that I have no need to spoil my memory of Venice from early childhood, which I see rather as a perk, nor do I feel a strong need for artists telling me – by way of installing warning balloons for example, balloons indicating a future sea level, that Venice once, due to rising sea level, might become a new Atlantis. I find this very trivial. If I want to ›see‹ Venice in the clear light of winter, I can turn to reading Joseph Brodsky; and if I want to see Venice with the eyes of Hemingway, I can read Across the River and into the Trees, and I am even recommending that book – but only for its first part and for the way Hemingway has staged a most beautiful arrival at Venice. It may be a (virtual – literary) arrival by car – but I see no reason not to be happy with that.

But what about Miami?

I have never had the chance to visit Miami (but I have seen pre-Katrina New Orleans), and I have read a recent article by journalist David Signer about the future of Miami. Will Miami become Venice first, only to become another Atlantis? And how are real Miami real estate developers dealing with that? For all that I am recommending the article by Signer, a very appreciated journalist, who also mentions the story of that one octopus that, some years ago, had been found – and photographed – in a Miami parking lot. Do we see here a ›metaphorical‹ writing on the wall here, in terms of that one octopus? Or are we just inclined to interpret, due to a global climate change discourse, such images as a writing on the wall? At any rate: that one octopus does belong into a pictorial atlas of sustainability, for whatever flood it was that brought him there.

(Picture: Richard Conlin ; telegraph.co.uk)

Youth (intergenerational fairness):

(25.4.2022) What about wisdom? Is it rather with the young activist or with the – let’s say – more mature but somewhat disillusioned elder journalist? Was wisdom with my 20-year-old self in 1992, rather than it may be with me now, some decades later, and realizing that, the Earth Summit of 1992 is less remembered for its outcome (the Agenda 21) than for a young girl, Severn Suzuki, allegedly ›silencing the world‹ by giving a speech? Do we have to come to the conclusion that the iconography of sustainability is actually – an iconography of youth (which may be something sustainable or not)?

If, voting for the more broad perspective, we are inclined to ask the age of Bruegel and Bosch for an answer, we get a most precise answer from Bosch connoisseur Stefan Fischer. Who writes, in his impressive Bosch glossary (published in the magazine du in 2004), under the header of Youth:

»Youth does get away badly [in Bosch]: man elapses the vicious circle of vice, especially luxuria, only grey-haired and after having become wise like the Wayfarer [on the left], the Hermits [below] or the eldest of the magi in the Adoration of the Magi (Madrid, Prado) [on the left]; the youngest king shows bird sirens on the hem of his garment, indicating luxuria [on the right].« (my translation from the German)

A German television channel, perhaps pondering about the same question as I am here, had an intragenerational encounter organized and even – on some level – curated. An encounter between a young German activist (Carla Reemtsma) and an elder somewhat disillusioned journalist (Jan Fleischhauer), and had them discuss climate change. The encounter had the two of them – which is why I am calling the encounter ›curated‹, switching positions and taking also the view of the other side. If this experiment really succeeded, I couldn’t say. At least it resulted with something interesting, highlighting the question I am raising here. Again: Was wisdom with me in 1992, or may it be with me rather now, highlighting the iconography of sustainability, including, perhaps, an iconography of disillusionment, perhaps frustration (see picture below). A minority of youth might be voting for modesty and even sacrifice. While the elder generation is definitely guilty for having built a consumer society without boundaries.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS