M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

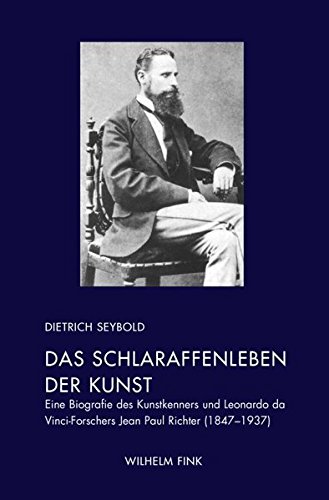

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Picasso (Not) Travelling to Moscow 1 (1947)

(29.1.2023) An exercise in biographical writing: we know that in 1947 Pablo Picasso had the chance to attend the 30th anniversary festivities of the October Revolution in Moscow on November 7, 1947 (AdP, 302). The Association France-URSS had offered him the chance to be part of their delegation; Laurent Casanova, who on part of the French Communist Party was the one to deal with the intellectuals of the Party, had passed this offer to him (and Casanova himself, as well as Party leader Maurice Thorez, with Jeannette Vermeersch, did attend these festivities (see Bulaitis 2018); Thorez was to meet Stalin for more than two hours on November 18) but Picasso did not travel, in 1947, to Moscow, nor when he was invited officially (in 1954). Why not? Do Picasso biographies tell us? If yes, what do they tell us, and if not – what mot make of all this?

Selected Literature:

John Bulaitis, Maurice Thorez. A Biography, London etc. 2018;

Gertje R. Utley, Picasso. The Communist Years, New Haven/London 2000;

Alessandro Brogi, Confronting America. The Cold War between the United States and the Communists in France and Italy, Chapel Hill 2011;

Pierre Daix, Pablo Picasso, Paris 2007

(Picture: Argentina)

The year 1947 is (as 1956) another pivotal year of the Cold War. It is the year when the Truman doctrine was defined and the Marshall Plan proposed (opposed by the French Communists, who, because of that, had to leave the French Government in May); it was the year when the Cominform was founded, it was the year in which a logic of polarization established itself (to use a neutral word), brief: the Cold War had, with Cold War structures, imposed itself on the world. But virtually nothing of all that we get to know from Picasso biographies (with one exception). It is as nothing of all that, despite of Pablo Picasso already being a member of the French Communist Party (since 1944), had anything to do with Picasso, who, however, already was one of three walking advertisements of the Party (with writer Louis Aragon and scientist Frédéric Joliot-Curie), and who, even if he was to do nothing at all, represented Communism with everything he did. Well, not with everything, but we will come to that. If Pablo Picasso was unpolitical by nature, his role was not. And this is the basic paradox we have to deal with here. Nothing really fits together in this story (of Picasso being a member of the Communist Party), and this is exactly what makes this story interesting and worthy to be looked at. Because it highlights any kind of tension within the communist sphere, as well as any tension in the world of the Cold War, any problem of being an artist as well as an activist, and any question of artist’s responsibility and credibility in a highly polarized world. And the problem shapes here, in the fall of 1947, in the year 1947, and I would dare to say that it shaped without Picasso actually being aware that it did so.

Thorez is seen in the front row, third from right, as being part of the Ramadier government

which he was to leave in May 1947, because the French Communists did oppose the Marshall Plan

The Artist Stalked

The fall of 1947, as well as the summer, Picasso spent, with Françoise Gilot and newborn son Claude (and with a maid), in Golfe-Juan. And what most biographers tell us is that he had just discovered pottery. Okay, these are the basic facts, these basic facts are undisputed, and a biographer can develop a narrative from that. This can go in the direction of showing toxic masculinity as well as the personal mess that this masculinity had created and was creating, showing Picasso rightfully stalked by his wife Olga, and trying to impose his dictatorship on Françoise and so on.

Or it can go in the direction of ignoring all the personal things by focussing on the art that was created in 1947 (very little painting, few drawings, a play being written (or begun), poetry illustrated (or continued to be illustrated) etc.). Picasso returned to Paris in December, and this is it. But such accounts remain rather one-dimensional, and, obviously, a political dimension would be completely lacking, not only a reference to an invitation to go to Moscow declined or ignored. But it is necessary to leave everything out?

I would say that at least raising the question if the whole political context of 1947 in any way affected Picasso is necessary at any rate. Because at least raising the question would avoid to repeat what Picasso perhaps did: taking his role as a walking advertisement of the French Communist Party and of World Communism far too easy, and this exactly at the time it might have been of the highest importance to be alert, just because it was the time when structures established themselves (and the French Communist Party was more rigidly guided, from now on, by Stalin).

And apart of avoiding biographical reductionism, such strategy does allow to enrich a narrative that, of course, has to encompass the private as well as the creative dimension, with several layers. Pottery, for example, was seen as something that brought the artist Picasso closer to the artisan and the worker. And even if Picasso would not have cared – this was a way his doing of ceramics was seen in the coming years. And the propaganda for the Marshall Plan, which encompassed posters with peace-dove like birds (see Brogi 2011, 140), actually preceded Picasso joining the Peace Movement in the next year, in 1948, and Picasso accepting one of his dove-images being chosen as an emblem of the Peace Movement (the choice was that of Louis Aragon). What happened later, in 1948, in 1949, had much to do with what had happened in 1947, only we are not told so in Picasso biographies, probably because art history oriented biographers do care too little for general history, but, in doing so, also miss relevant dimentions of the art (or artistic creation).

With the Exception of Pierre Daix

The Picasso biography by Pierre Daix (Daix 2007) is the one exception that does not ignore the political context as for the year 1947. But Daix became only closer to Picasso in the next year, in 1948, and not in 1947. And what Daix does is to stress that Picasso, in his view, was standing above all the political mess generally, including above all doctrines, in complete freedom, which, in my view, is rather ignorant as to the political role that Picasso had at the time, even if he might have more or less ignored the implications of that role, at least in the beginning, because later he did become aware of all the ambiguities.

And this narrative, apart from Daix blurring the chronicle of these years with suggesting that things that happened actually in 1948 were already relevant for 1947, also is avoiding to ask the question if Picasso was actually aware of what was happening in 1947. It would be only natural that he was not, that he could not see what, for example, historians can see in hindsight (which would mean that, generally, the important things would happen without ourselves being aware of them happening, which is unsettling, but probably true), but this is not completely true either: Picasso did make decisions, also in 1947, decisions also of, probably, not reacting to certain things, and deliberately taking certain things easy. For example the attack on him by Soviet painter Alexandr Gerassimov in the Pravda in August (something that Daix does mention, while most Picasso biographers do not even know Gerassimov and his role). Or perhaps Picasso did also deliberately not react to the aforementioned invitation to attend festivities at Moscow. Did he get the invitation at all?

It is likely that he knew of the invitation in time, because post was sent to him from Paris to Golfe-Juan as well as newspaper clippings. But as a matter of fact, this invitation seems also to have been completely unknown to Daix. Might it be that Picasso travelled, despite his general dislike for travelling, to Poland in 1948, just because he had not travelled to Moscow in 1947, as a sort of concession to his friends asking him to join the communist activities more actively?

Contributing to the Cult of Personality

At this time Picasso had already contributed to the cult around the leader of the French communists, Maurice Thorez. By contributing a Thorez portrait drawing to the autobiography of Thorez (which was actually written by a ghostwriter). Because this book was part of the cult of personality as far as Thorez was concerned. And one may ask, if Picasso was aware of what he did. Just as one may ask, why, if he was to complain repeatedly, in later years, that the Communist leaders were not taking him seriously, by not telling him anything about political interna or strategies, – why did he himself not take the culture of the French Communist Party seriously soon enough, that there was also a culture of security and secrecy that simply did not allow that someone like Thorez or Casanova actually would have revealed to party intellectuals what was going on on a level of party leadership.

Would this have been different if, in the fall of 1947, Picasso would have travelled to Moscow, as Casanova and Thorez, or even with them? Probably not. In 1947 Picasso was not yet the designer of the internationally popularized Peace Dove emblem, and his aesthetic was, as mentioned, the target of Soviet criticism. Yet Laurent Casanova had been among the personalities that had probably inspired Picasso to enter the Party, but it is highly unlikely that, after the festivities, Picasso would have gotten to know that Thorez had conversed, for more than two hours, with Stalin personally, or that he would have gotten to know about what (the transcript of that audience is published). But perhaps Picasso would have gotten to know earlier or more precisely, by what context, also by what organizational context, his role as a Party Intellectual was defined from now on. And if he was seen to stand above all this (which is a hindsight perspective, and probably to some degree also a projection by Daix, who needed Picasso as such guiding figure, towering above everything), this is at best a part of the truth. He might have cared little about doctrines, yes, but he did clash with them, and his credibility as an artist was to be challenged dramatically by the Stalinist era, the Stalinist-Cominform-era, that had just begun. In the fall of 1947 (with the first of the Eastern European show trials just taking place in Bulgaria), and with Picasso rather paying little attention to everything political, also due to his role as a father perhaps – than standing above everything knowingly, as Pierre Daix tended to suggest.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS