M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

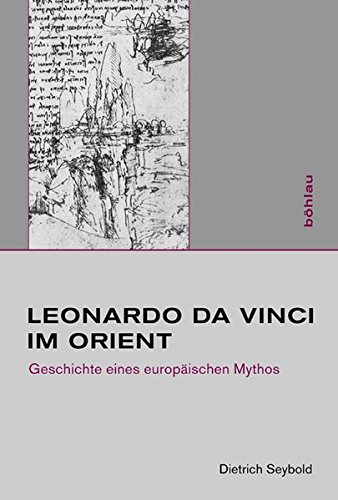

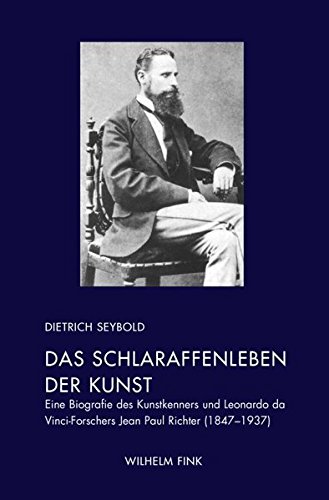

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Three Veils |

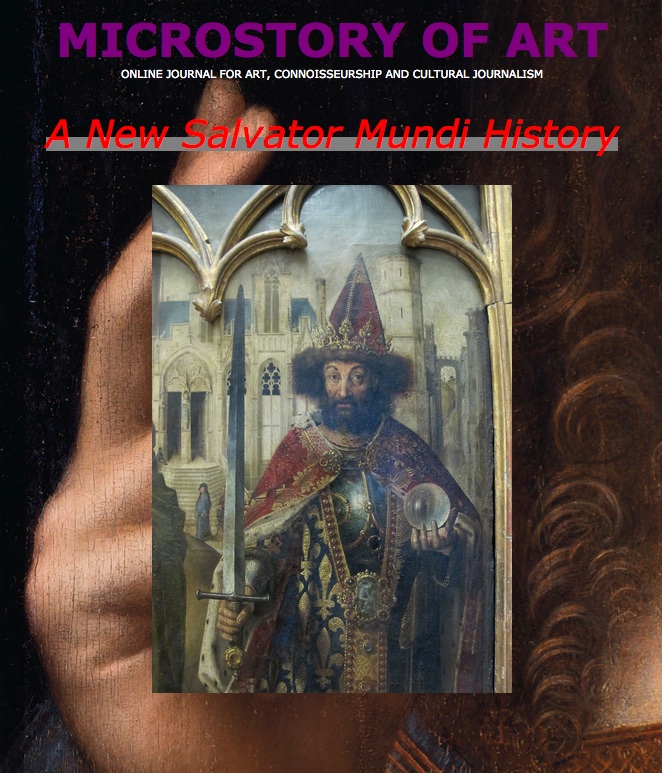

See also the episodes 1 to 26 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

A Brief History of Digital Restoring

Learning to See in Spanish Milan

And:

Three Veils

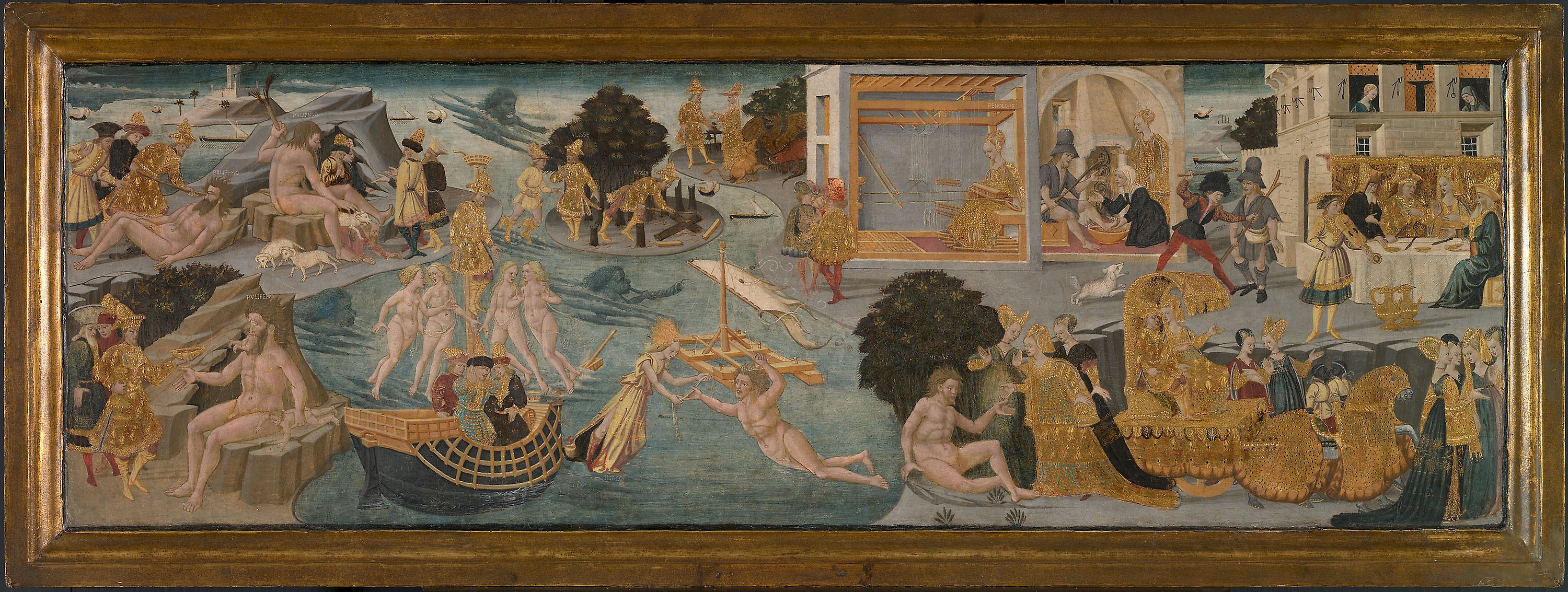

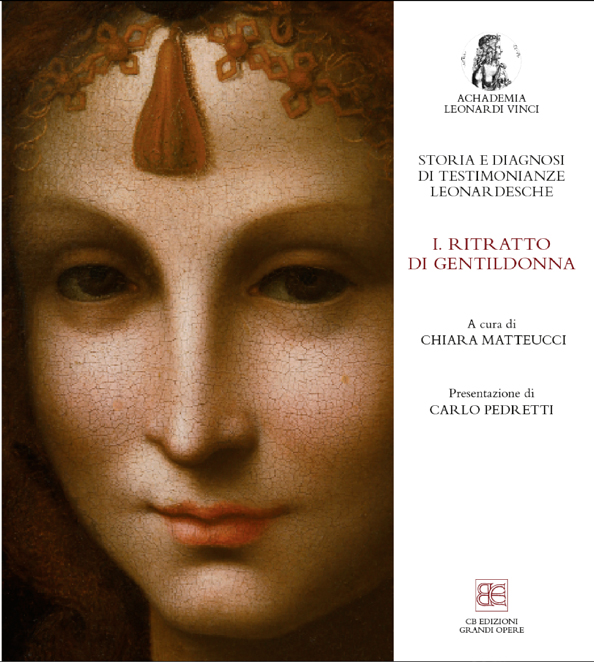

(24.-25.10.2021) This 27. episode of our New Salvator Mundi History is meant to intensify Pomona scholarship. In other words:

It is meant to intensify Francesco Melzi scholarship, and we are assembling and showing here, perhaps for the very first time,

the essential sources and documents as to the Pomona and Vertumnus in the Berlin Gemäldegalerie (above) – a Melzi-attributed

picture and, perhaps, the most important Melzi-attributed picture, since, as it seems to be the case, it once had beared

a signature, attributing the picture to the perhaps most mysterious of all the Leonardeschi, a signature that, during the

1990s, had been spotted again (but then, alas, had been forgotten again).

We will also muse about the motif of the veil, in connoisseurship, but also in Gender Studies or Cultural Studies or

other fields of study that could, potentiall all, assemble in the arena of connoisseurship, to contribute something to

connoisseurship (but it had to be something other than mere ideology, it had to be based on observation), and at the end,

when we will come back to the Pomona, we will raise the question of what further could or should be done in Melzi

scholarship, after we wil have found out to which degree it had been neglected.

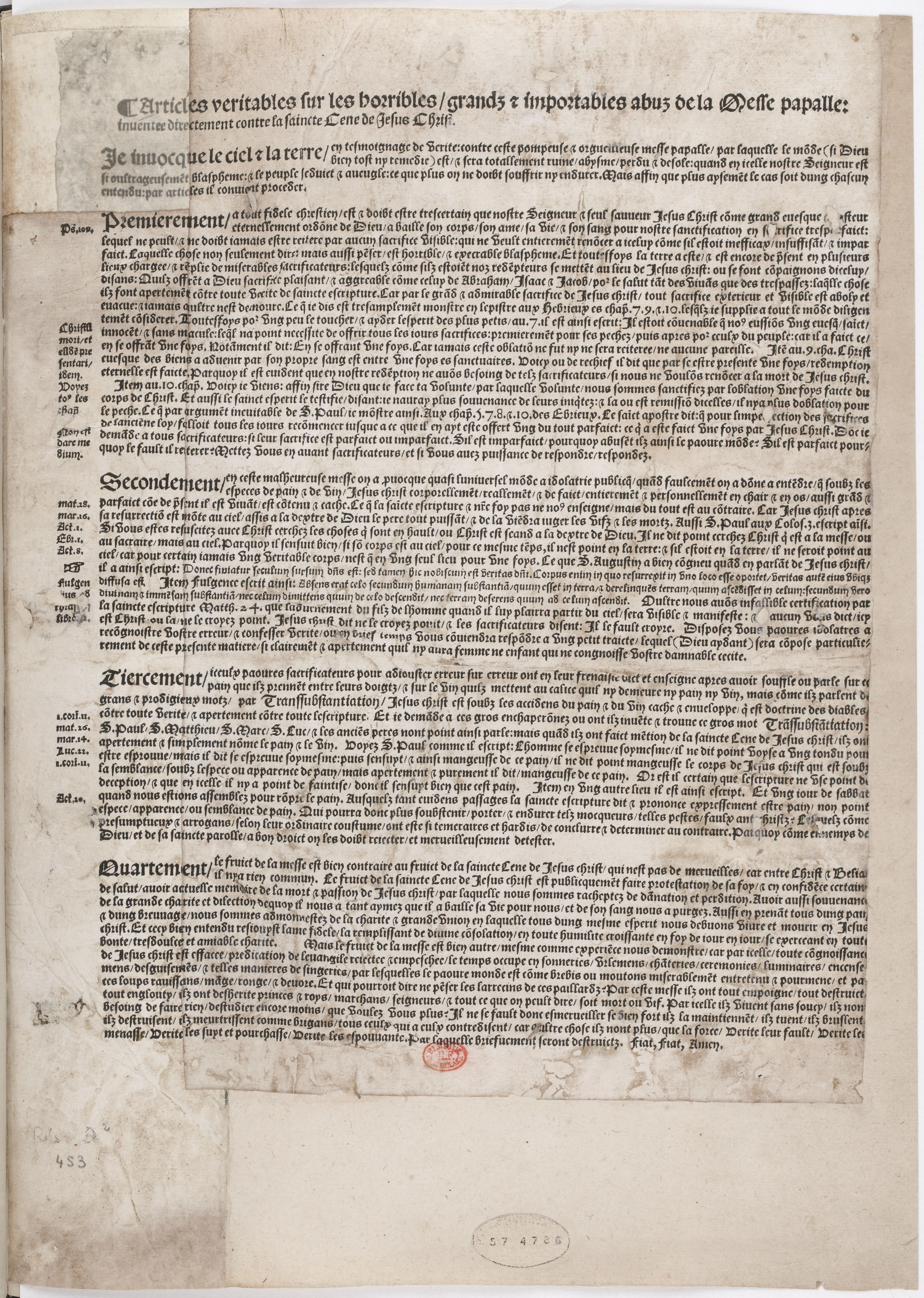

One) The Pagan and the Christian Veil

The politics of the veil have a long history. We find such politics in Homer and Paul the Apostle, to name representatives of the

pagan as well as the Christian tradition, because these traditions we see intersecting – perhaps coexisting – at the time

of the Renaisssance, and we might start with looking at a fine representation of the adventures of Ulysses (above).

Ulysses, who has only survived a storm, because the goddess of the sea had borrowed him her veil – something that he had

to give back, after having reached a shore. And having reached a shore he is rather immediately confronted with politics

of the veil as well. Since Nausikaa and her companions – at least in the text – have put aside their veils to play ball,

and so on. What we see in the above example is a Ulysses, getting the veil of the goddess of the sea (in the center), and

a Ulysses, being confronted rather with strict cultural conventions as to clothes and nudity, or, having been painted

rather by a master sticking to strict conventions as to unveiled nudity in art (later artists handled the subject of the

Nausikaa episode less coyly; and also Giampietrino might have found the painting a bit reserved).

With this picture we already have touched a number of sensitive issues – because almost every aspect of veil history

seems to be sensitive –, such as the veil as, usually, rather defining the boundary between human and pagan god, also

something that protects humans from being, directly, confronted, with divinity; and the Nausikaa episode might speak for

itself. Veil, as well as hair, can be though as something to cover, which has to be covered, or as something to unveil

something that is supposed to be, or could be unveiled, even if unveiled nudity, not necessarily is what, in the end,

painters or viewers (male or female), are striving for. The striving for, or briefly: desire as such, might be the

essence of what the veil is about, as well as control of desire, might be the or one essence of veil politics.

Which, in the Christian tradition, have a prominent, but also very controversial exponent with Paul, who, as the layman

notes, said things about the veil that triggered a tradition of commentary and interpretation that has not come to an end

(one is not sure, to be frank, what actually and exactly he did mean, and how it is to be interpreted and implemented in

veil politics). And Christian tradition has, with the veil of Veronica, and with the Maphorion (the veil of Mary),

further traditions that certainly every artist of the Renaissance was familiar with. Actually veil politics, at the point

of intersection between theology, politics and art, are so sensitive that one might also attempt to classify artists as

to their point of view and way of expression. But as far as I can see such classification has not yet been undertaken.

Two) Lomazzo and Melzi

What is striking with Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, our first witness as to the politics of the veil in Leonardo and the Leonardeschi, is that

he seems to look at the veil as a painterly problem only. Not that I would trust that statement on the spot, but this is

what he says. And he says the following:

»Di Leonardo è la ridente Pomona da una parte coperta da tre veli che è difficilissima in quest’arte, la quale

egli fece à Francesco Valesio primo Rè di Francia, […]«

Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, Idea del tempio della pittura, Milano 1590, p. 132

What Lomazzo does not say, to name this right away, is that the besaid Pomona was at Fontainebleau, but Lomazzo is

associating a Pomona with Francis I, King of France. And the difficulty with Lomazzo is, to name this right away as

well, that, according to what he says explicitly, he must have been in touch with Francesco Melzi (who, according to

Lomazzo, told him things), while on the other hand, Lomazzo is saying things about Leonardo that sound doubtful to us,

although we may assume that Lomazzo indeed had been in contact with Melzi. But this does not necessarily have to be a

contradiction, because we don’t know how intense such contact with Melzi might have been. But it has to be noted that

Lomazzo, for example, speaks of the ›Monna Lisa Napoletana‹ (which is a statement as delicate in the context of Mona

Lisa scholarship, as is all veil politics delicate alltogether, but Mona Lisa scholarship and/or obsession is not our

concern here).

The question Lomazzo leaves us with is the question if, with the Pomona, as well as with the three veils, he is

referring to the Berlin picture, and if yes, if this picture is by Leonardo, and if not (and if the picture is by Melzi),

why is Lomazzo not saying so, if he had been in touch with Melzi, who might have informed him about things.

So Lomazzo is not necessarily making things easier for us. Rather his statement has to be named as the statement at the

beginning of much confusion. And what we are attempting here, is, in a way, only to make this confusion more transparent.

Finally: as I am writing in late October and in a beautiful autumn (if not exactly in autumn light), it seems to me (as

probably to many other viewers) that the Berlin Pomona and Vertumnus is yet luminous in colour, but painted rather in

a local-colour-oriented style, and not in a style that goes to extremes as to the representation of atmospheric

phenomena, as, perhaps, we might expect from Leonardo. And this style of the Berlin picture, has, by convention, been

referred to as ›Melzi‹, and one has associated other pictures in a comparable style (usually also pictures with flowers

or at least many plants) with the Berlin picture and with Melzi, so that this artist, on some level, was born (in the

context of art history). His style, as one may add, was not one meant to be inspected from whatever distance, but rather

one that works considerably well, if viewed from a certain distance.

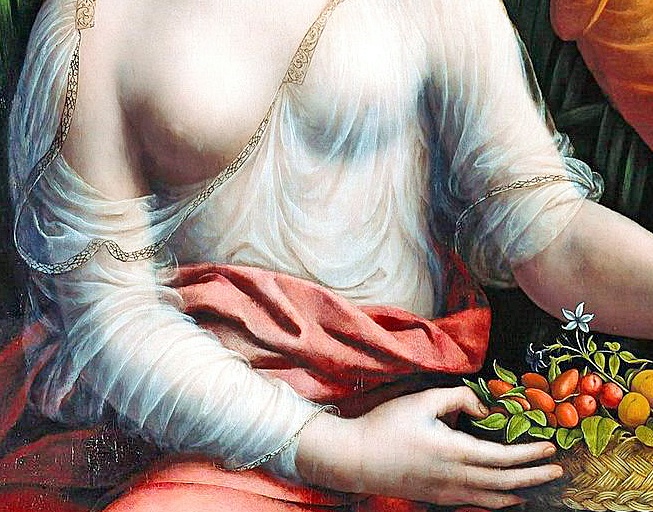

The Hermitage Flora (below), however, one of the aforementioned pictures and despite the nudity, does not depict a Flora

(or Pomona) covered with three veils (or a three-fold-veil, or whatever exactly Lomazzo does mean).

Three) From Mariette to Morelli or From Certainty to Scepticism

His late birth as a painter (or his creation as a myth, to name that possibility as well and on the spot) Melzi owed to

the 18th century connoisseur Pierre-Jean Mariette, who displayed self-confidence as a connoisseur in his statement,

and a self-confidence that, as we will see, is in striking contrast to what Giovanni Morelli was going to display a

century later. But first we have to listen to what Mariette said:

»MELZO (FRANCESCO). Il n’a pas seulement peint des miniatures; il a aussy peint à huile dans la manière de

Léonard de Vinci son maître. M. le duc de Saint-Simon a un tableau qui est de luy. Son nom et sa qualité de gentilhomme

milanois, écrits en grec dans le fond du tableau, ne laissent aucun lieu d’en douter, et cependant il avoit toujours

passé pour estre de Léonard jusques à ce qu’un habile curieux eût fait remarquer cette inscription; il m’a assuré qu’il

estoit peint avec sécheresse. — Je l’ai vû et j’en pense de même. J’ajouterai que la composition en est misérable; le

sujet est Vertumne et Pomone; cette dernière est représentée nue. Le tableau est entre les mains d’un brocanteur qui

cherche une duppe, et, pour empêcher qu’on ne le donne à un autre que Léonard de Vinci, il a eu soin d’effacer

l’inscription.«

Charles-Philippe de Chennevières / Anatole de Montaiglon (eds.), Abecedario de J. P. Mariette et autres notes inédites

de cet amateur sur les artes et les artistes, Paris 1856, vol. 3, p. 378f.

By referring to Melzi as a miniaturist Mariette was referring probably to Lomazzo, who had regarded Melzi as such

(another Lomazzo-Melzi-mystery, perhaps, but perhaps also no mystery at all, because, after returning home from France,

Melzi might have indeed reduced his painterly activity, turning to miniatures, to teaching, to painting on a smaller

scale, and to the editing of Leonardo’s manuscripts). Perhaps Melzi had also been rather modest, but this exactly is the

question, because someone who signed a work as the Berlin picture might also be seen as someone displaying his

self-confidence. And there might be, on the whole, much less reason to apply Melzi signatures on Leonardesque pictures,

for the owner of a picture, than to scrape them off, and if Mariette, very decidedly informs us that he had inspected the

picture, he on the one hand appears as a sceptic in Leonardo studies (and attribution), and self-confident as a

connoisseur (even if he is wrong in calling the composition of the Berlin picture miserable.). One has also questioned if

he was referring to the Berlin picture at all, since Mariette is referring to a nude Pomona (see the early 20th century

Berlin gallery catalogue), but this might just be due to the ambiguity of what a veil is, unveiling something more

strikingly than mere nudity does, or covering something more strikingly and ambiguously as other clothes usually do.

Giovanni Morelli, the advocate of scientific connoisseurship, did not trust Mariette, nor the curators of the Berlin

gallery. In fact Morelli was a deeply sceptic man, and I have considered his doubts and his scepticism as a connoisseur

as his strengths as a connoisseur. Even if, in this case, I do seem to have reasons why not to follow Morelli’s

scepticism. Which, on the one hand led him to question everything about Melzi, but on the other hand also to do Melzi

research (as far as documents are concerned); and in the end Morelli left the question of the Berlin picture and its

author undecided, claiming that, if it had not been painted by Melzi, he would not know another author. A very Morellian

ambiguity, in the end, very characteristic of the man and his methods, that easily are being misunderstood, especially by

people not willing or able to hear both: the scepticism and certainty.

»Nun mögen meine Leser mir erlauben, einen Moment noch bei dem Bilde Vertumnus und Pomona zu verweilen, da

dasselbe seit langer Zeit schon einem Meister zugemuthet wird, von dem kein einziges beglaubigtes Werk bis auf uns

gekommen ist; ich meine den Francesco Melzi. Bei Nennung dieses Namens möchte ich vor allem, die Präliminarfrage

aufwerfen: hat es denn im eigentlichen Sinne des Wortes je einen Maler Melzi gegeben? Trotz aller Nachforschungen ist

es mir wenigstens nicht gelungen, ein authentisches Bild dieses Freundes, zum Theil auch Zöglings des Lionardo da Vinci

ausfindig zu machen.«

Ivan Lermolieff [Giovanni Morelli], Die Galerie zu Berlin, ed. by Gustavo Frizzoni, Lipsia 1893, p. 141

Was there a painter Melzi? Here are the reasons why I am thinking that there indeed was one:

Because Leonardo da Vinci decided to bequeath everything related to his profession as a painter to Melzi;

because Antonio de Beatis saw an able pupil of Leonardo (or heard about his qualities, probably from Leonardo) at

Amboise. And it is quite unlikely that this pupil was Salaì, the only other candidate;

because Melzi is named as someone painting well in a 1520s source, whose author yet relativizes his judgment by saying

›per quanto intendo‹, but this is not necessarily to be translated (as Morelli does) as ›as far as I have heard‹, but

has also been translated as ›as far as I can judge‹, implying that we hear an eye witness.

because indeed we have a group of pictures, assembled due to stylistic peculiarities as named above, a group that we cannot

simply attribute convincingly to another name;

because there are statements such as that by Mariette, that not easily can be explained away;

and because we have also references to Melzi as having been a teacher or at least a reference for Girolamo Figino, a

painter having been rediscovered only recently.

And all of the above makes me say that Morelli, in this case, might have been too sceptical, even if his scepticism,

also in this case, is most valuable, because it forces us to name the reasons why we still can regard Melzi as more

than just a myth as a painter, and why we cannot solve the ›Melzi problem‹ by just ignoring it.

Two drawings, by the way, to be associated with the Berlin picture, one in Windsor and one in Milan, I am neglecting

here; the Windsor drawing of a face can be seen here; a picture of the Milan drawing of a foot is supposed to be in the

so-called Codex Resta in the Ambrosiana; I do not have any picture of that drawing.

The 19th century further did unfold the interpretation of what Lomazzo had called three veils, or better: it did unfold

further imaginations of what a veil in art might mean. The striking example is the occultist Joséphin Péladan, who,

in this respect, has to be heard:

»Léonard avait peint une Pomone, renommée pour l’exécution du triple voile qui la couvrait. Il faut entendre qu’elle

réunissait dans une combinaison subtile les trois saisons de la beauté: virginité, nubilité, maturité, ou

s’adressait-elle en même temps aux sens, à l’âme et à l’esprit?«

Joséphin Péladan, Pomone, in: Joséphin Péladan, La décadence latine, vol. XX, Paris 1913, motto on title page

Recent scholarly literatur has claimed that Péladan, with the above statement, was paraphrasing Lomazzo, but this, as

can easily be seen by comparing the statements, is not exactly the case. Lomazzo did not speak of three seasons of

beauty, nor did he speak of the three veils, respectively the triple veil other than referring to them/it as a painterly problem.

Four) The Veil of the Leonardeschi

Since a veil in a painting can be regarded as a highly demanding painterly problem in terms of finesse, but also in terms

of an artist defining his stance in the context of any politics of the veil, a veil can be regarded as an extraordinarily

interesting criterion of distinction. And it would be a rewarding task to assemble all veils in Leonardesque paintings

in order to study this crucial criterion of distinction more systematically. This is not our aim here, but a few hints

may still be given. I see veil connoisseurship as potentially rewarding in three distinctive contexts:

1) The relation between the Melzi-attributed Berlin painting and the Prado Mona Lisa (picture above right:

flickr.com/Lomovolga; detail from) could be studied in close detail. Also for the latter painting Melzi has been named

as a candidate (by the Prado), while it seems that, presently, the museum prefers to speak rather of an anonymous ›pupil

of Leonardo‹, avoiding now also the naming of Salaì (who, earlier and little convincingly, had been the alternative

candidate of the museum);

2) Since several of the Leonardeschi embarked on further developing the (usually mythologized) nude in painting, and

since in many of these paintings also the veil is a crucial motif, a more systematic study of the veil could result in

finding clues as to authorship (currently we have a far-ranging confusion, with arbitrary attributions being suggested

and dismissed again and again, without actual progress in scholarship; examples might be two paintings (occasionally also

associated with Melzi) of nymphs (?) in a landscape (see above and below), which also might be discussed in the context of

discussing the consortium of painters headed by Bramantino (and Zenale) in around 2011; links to Giampietrino and Marco

d’Oggiono, both members of that consortium, as well as to Luini, should be studied more systematically (the National

Gallery of Washington seems to have sticked to a Luini attribution as to the painting shown below, although a Melzi

attribution had been suggested by Pietro C. Marani);

3) The whole complex of the Madonna with a Yarnwider versions could be studied more systematically; we see two groups

(with and without a veil, as far as the representation of Mary is concerned); we see a Spanish group, which raises the

question, if the Spanish Leonardeschi transmitted the motif by transmitting (copies of) a cartoon; which further raises

the question, if not the the most complete versions (showing very distinctive motifs in the background) could be

interpreted as a – perhaps very late – going back to the earliest versions of a design; the question if the existence of

a cartoon does allow – and also here – very complex chronologies of versions should be taken more seriously.

But the most crucial context for veil studies, in our context, seems to be the potential identification of Melzi as the

author of the Prado Mona Lisa, as well as the potentially more decided identification of Melzi as the author of the

Berlin picture of Pomona and Vertumnus (picture above and below: flickr.com/Lomovolga; details from), on the basis

of a decidedly more committed discussion of the topic of a signature in the Berlin painting (below the notorious rock,

on which, earlier, a signature, respectively remnants of a signature had been spotted).

Five) A (Missing) Signature and Some Conclusions

The way the question of the signature in the Berlin picture was handled is a good example of the way Leonardo scholarship

is often handling things: in a too-casual, occasionally even negligent way. This casualty, combined with a general

disinterest in Leonardeschi studies, and set against a background of general slow motion in the academe, makes Leonardo

studies miserable and mediocre. There would be other ways, more worthy ways also. And here is what happened:

In 1994 a student named Peter Hohenstatt completed his studies at Berlin with a Magisterarbeit (thesis to complete

the degree of master) on the Berlin Pomona and Vertumnus. This thesis seems to exist as a typoscript, and it seems

also that Leonardo scholar Pietro C. Marani had been made aware of this thesis and that a further publication on the

subject of the Berlin picture was planned (see Legacy of Leonardo, p. 373ff.). But such publication does not seem to exist.

One can assume, due to the informations Marani had, and had also inserted into his discussion of Melzi, that the picture

had been cleaned, and that, after cleaning, it had appeared to Hohenstatt or to the Berlin curators, that parts of the

signature mentioned by Mariette could still be read (or again be read). The photo in Legacy of Leonardo is not very

telling, and after the publication of Legacy of Leonardo, it seems, no-one seems to have cared about the question

anymore.

Now, some 27 years after the Magisterarbeit by Hohenstatt, we still do not see any progress in Pomona

scholarship, and online resources available as to the Berlin picture are scarce. No documentation can be found, and in

the meantime, technology has also progressed.

What I hence would propose, given that progress in Pomona scholarship would be wanted, and given that we have progress in

technology, is to have Pascal Cotte, with his camera, inspect the Berlin picture, and particularly the rock at the feet

of Pomona and Vertumnus, to have the camera look at it and at the remnants of the notorious signature, and to have the

results of such inquiry inspected by Leonardo and Leonardeschi scholarship. I am rather certain that we would see

progress, while I don’t know, of course, in what direction. If yet a signature by Melzi could be indeed detected, we

would know a lot more about which parts of the tradition recalled above, might be called trustworthy, even if a signature

could not be regarded as decisive proof for Melzi authorship. Still we would see an earlier testimony as to a tradition,

perhaps, thinking that Melzi indeed had been a (perhaps modest) painter, who had to be forced to be born. As a painter,

and possibly, yes, this possibility does exist as well, as a myth. I don’t think that Melzi was a mere myth as a painter

(and for Leonardo he certainly was not), but more energy is needed, and the will to know has to be rediscovered, to find

out. More. If perhaps the full truth will never be uncovered (detail picture above and below: flickr.com/Lomovolga;

detail from).

Further Reading:

Paul Hills, Veiled Presence. Body and Drapery from Giotto to Titian, New Haven/London 2018

The Bottega of Leonardo da Vinci

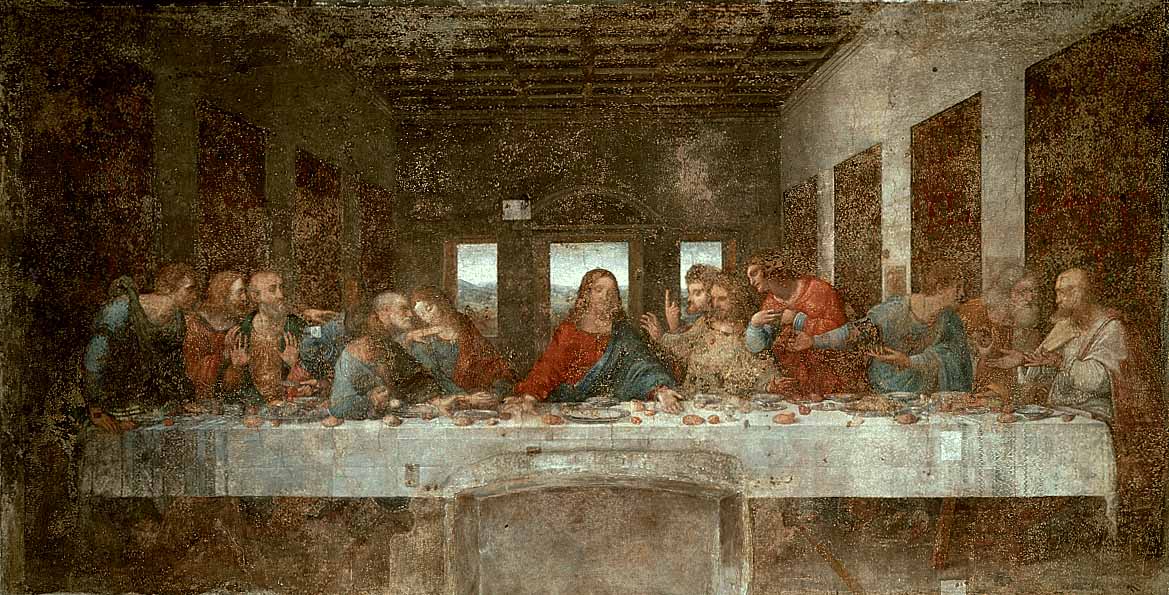

The picture of the bottega of Leonardo da Vinci is not as blurred as one might imagine (for details see Seidlitz 1935, p. 530; Marani 1998). We will focus here on the early and middle years (up to 1512), and not on the late years, and one might begin with saying that with Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono we see two figures enter the orbit of Leonardo at the beginning of the 1490s that we believe to know rather well. We also see Salaì enter the orbit, at a very young age, and we have, in addition to that, a couple of names, names of figures that we do not seem to know very well, or not at all (a Giacomo, Giulio Tedesco, Galeazzo). Last but not least we have the Giampietrino problem: Giampietrino enters the scenery, but it is a matter of controversy (as far as this question is debated at all), when, since also Giampietrino is still very young.

It is noteworthy that Marco d’Oggiono, already at the end of the 1480s, seems to have had an own apprentice, and that Marco and Boltraffio did create the Pala Grifi together (a picture today in Berlin; picture above), even before Leonardo began to work at The Last Supper in 1495. Due to the work of Janice Shell and Grazioso Sironi we today do know more about Francesco Galli, also called Francesco Napoletano, who did die in Venice as early as 1501. One might imagine that Galli went to Venice with Leonardo in 1501, and if Galli, during the 1490s, for example might have cooperated with Marco, we would have found an interesting perspective: since, if only one single picture of the Marco group would be associated with Francesco Galli/Francesco Napoletano, we would have a picture with hand option 2, a picture that must have been created before Galli died in 1501. Which would mean that hand option 2 must have existed early, and my theory of the pentimento in version Cook as a mere switching from (preexisting) option 1 to (preexisting) option 2 would be positively proven as well as the theory of the pentimento supposedly showing the creative energy of genius (changing his mind) would be definitively falsified.

Brief: in the 1490s Leonardo mentions once that he had paid ›two masters‹ (probably Marco and Boltraffio) for two years; and once that he had six bocche to feed (probably again Marco, Boltraffio, plus Salaì and some of the unknowns).

Below a rather early Marco picture (according to Janice Shell), the Young Christ Blessing of the Galleria Borghese:

And here is a picture (not the only known picture) by Protasio Crivelli, formerly the apprentice of Marco d’Oggiono (picture by Sailko; the date appears to be 1498; location: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte):

In 1501 (3.4.) Pietro da Novellara informs Isabella d’Este that Leonardo seems to live ›from day to day‹ (see Marani 1998, p. 14). And he has seen Leonardo intervening from time to time in portraits done by two of his garzoni (»fano retrati«). But who are these, and which portraits are these (if this would have been about a Isabella d’Este portrait, Pietro would have noted; and after the Sforza had been expelled, portraits of court ladies and courtiers made no sense)? After having written on the picture of a young woman in the Columbia Museum of Art in one of the last episodes, I would now suggest the following:

Leonardo might have done a portrait of a Sforza court lady in the early Milanese years (and still in the Florentine portrait style), a portrait in terms of a drawing or a cartoon. He might have begun also a painting, but since the Sforza court got expelled and exiled after the French invasion, he might not have finished such portrait. He might instead have used it for the instruction of his garzoni: the Columbia picture might have been the one begun by Leonardo (as he seems to have begun portraits with the face, as later in the Mona Lisa), a picture that he might have had a pupil finish, with him retouching it again, adding some lustre. The picture in a private Russian collection might be a second version that he had a pupil repeat (after the first version and the drawing, respectively the cartoon). The Columbia picture shows much gusto for the grotesque, the second version less so, but still to some degree. Thus we would see pictures that have their origins in the first Milanese period (and even in the early Florentine period), but were actually done later (after 1500). And Leonardo might have had a hand in the Columbia picture whose head with the hair as well as the ornated hair net superbly being modelled into the dark is of exquisite quality (as also a single one pearl is, while other pearls are rather mediocre as also the bust and the modelling of the dress is). We see, as I have attempted to show in episode 13, two pictures that fit into the context of Leonardo’s thinking and doing rather than into the context of Boltraffio’s autonomous work:

In 1504 a Jacopo Tedesco, in 1505 a Lorenzo (di Marcho) enter the orbit of Leonardo.

In around 1505 Fernando Yáñez enters the orbit of Leonardo, helping him with the Battle of Anghiari (as also does Riccio della Porta). Yáñez cannot be the author of the Prado Mona Lisa, if the Louvre Mona Lisa was finished only years later, since the dates (showing that Yáñez was active in Spain after 1506) do not allow to postulate it. In works of Yáñez done in Spain, however, we find echoes of Leonardo’s works (see the example below).

Around 1507 Francesco Melzi becomes a pupil of Leonardo (and also a sort of secretary).

In 1511 (or even earlier) Giampietrino is an autonomous master.

In 1511 Salaì seems to have created a (signed and dated) picture of Christ:

In around 1511 we see Marco, Boltraffio, Giampietrino and – Giovanni Agostino da Lodi in close contact, not only because we have a source indicating exactly that – we also have pictures indicating exactly that, and one of these pictures seems to be even dated (but the ›date‹ – ›XII‹ – is rather referring to the ›age of Christ‹):

The Prado Mona Lisa (below) was probably begun at the time Leonardo also started reworking or completing the Louvre Mona Lisa, probably due to Giuliano de’ Medici wishing so, and hence perhaps in around 1511/12.

In around 1517 Marco d’Oggiono is cooperating with Giovanni Agostino da Lodi (see Shell, p. 173).

***

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

»…in the evening at twenty-two o’clock we saw the Holy Sindon or Shroud«, Antonio de Beatis is writing in his travel account, his trip across Germany, France, the Netherlands and Northern Italy having enabled him to recall, as an eye witness, essential sights of the visual culture of Europe in 1517/18. These sights included, as said above, the Ghent Altarpiece, the Turin Shroud and also Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan (picture of the Turin Shroud: Dianelos Georgoudis). Only the now so-called Turin Shroud, however, did apparently stimulate him to include a visual reproduction, a drawing, into the manuscript copies of his account.![]()

See also the episodes 1 to 26 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

A Brief History of Digital Restoring

Learning to See in Spanish Milan

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS