M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

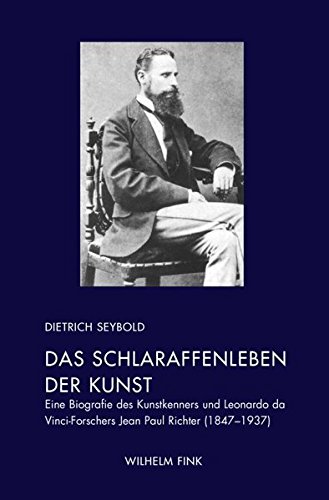

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

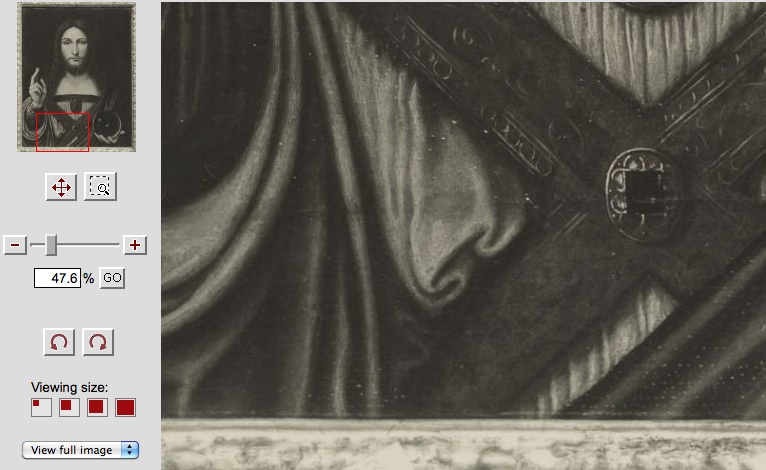

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

SPECIAL EDITION

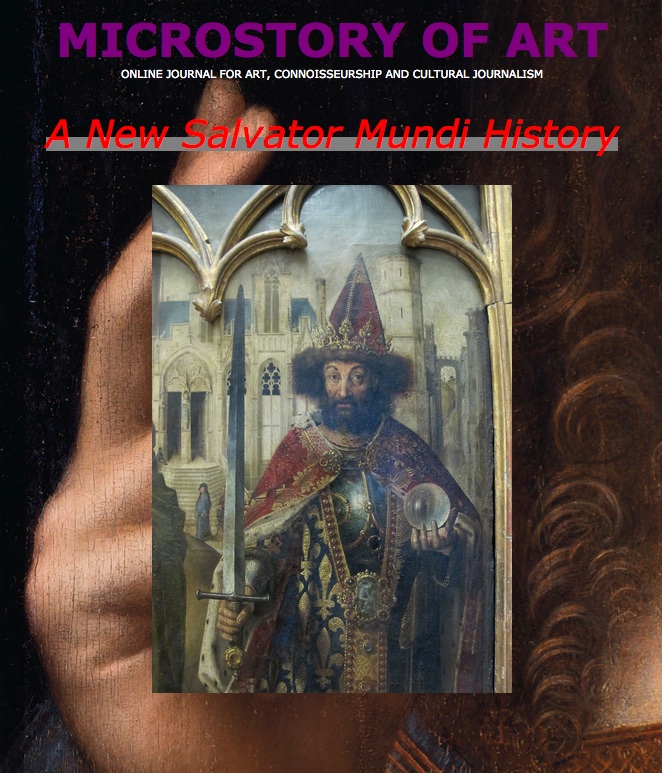

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Some Salvator Mundi Microstories  |

I’ve been observing the Salvator Mundi controversy from its beginnings, and it seems a good idea to me to assemble here – and to share – a few of my observations in an appropriate form. Not only because of the painting itself that has been attributed to Leonardo da Vinci (although most of the experts that went public, except Martin Kemp, seem only to regard parts of the painting as worthy of Leonardo; my own opinion also being a more sceptical one), but also since we are facing a Leonardo da Vinci year in 2019. Leonardo, who died in 1519, would certainly turn in his grave if he knew about his status today. But how to describe that status? It seems appropriate to me to speak of Leonardo really having become a figure of global imagination, and this is, beyond the attributional question, one of the fields I am interested in. Having written on the history of research, on Leonardo in a framework of intercultural history, on connoisseurial questions (not to forget), and particularly on the Leonardo’s notes as being inspiring to a whole line of writers and thinkers (beyond his achievements as a painter and engineer), I am sort of summing up here what I am observing. Unfortunately the public interest seems to focus on other areas that I am chiefly interested in, but never mind. A figure of global imagination is what I am seeing. Who does inspire people from all corners of the world. And the interest of these people from various cultures will sooner or later inspire new perspectives on Leonardo. Hopefully this will also inspire future research. Since a change of generations in research, as it seems, is due.

Arabia (Leonardo da Vinci and):

If one had asked Leonardo da Vinci about Abu Dhabi (and perhaps also about the Louvre Abu Dhabi), he would not have been able to place it on the map. But he was aware of the Ptolemaic geography, of the Persian Gulf (see further below), and also of the Red Sea, one of his main interests being the various seas, and particularly the various water straits on planet Earth.

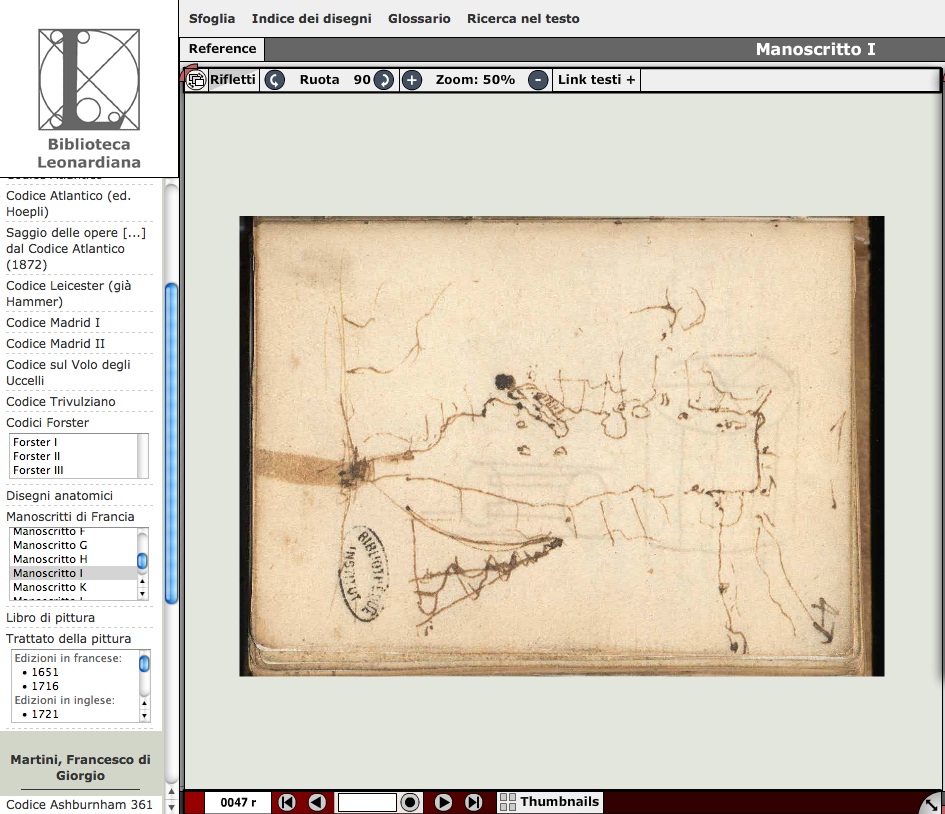

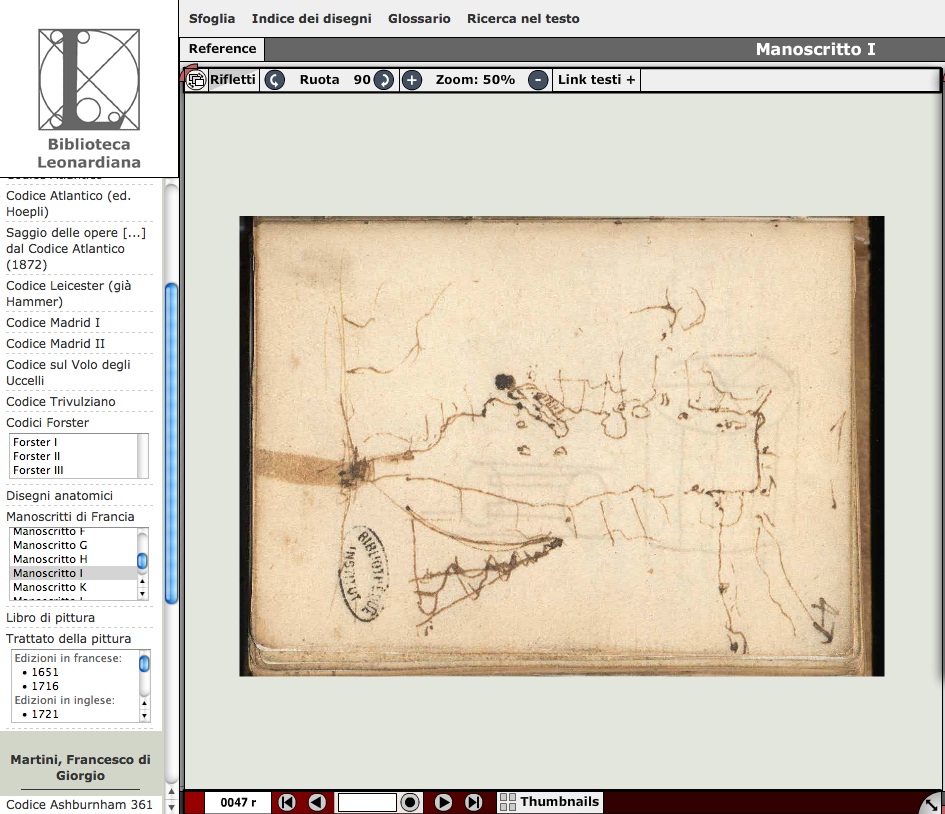

Here below we give his sketch of the Mediterranean Sea from Manuscript I (picture from leonardodigitale.com), which includes also the Red Sea and, as you can see, the western shore of the Arabian peninsula.

| From Ms. I (Sketch of the Mediterranean Sea with also the Red Sea and the Western shore of the Arabian peninsula) |

|

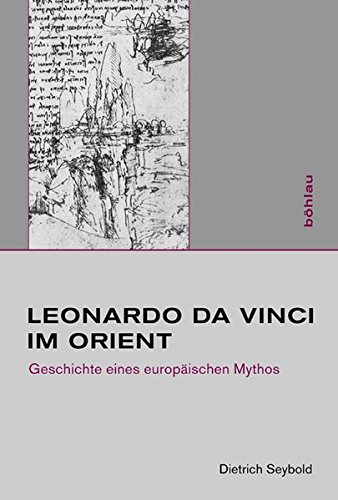

For an encyclopedic account on ›Leonardo Vinci and Arabia‹ see my: Leonardo da Vinci im Orient monograph, p. 329ff.

Beard:

Has the Salvator Mundi been shaved by time? According to the restorer who worked on it, this Salvator has always been beardless (a beardless Naples version she does regard as a copy after ›our‹ painting in question). In other words: if Hollar (see: Hollar Problem, the) had worked after ›our‹ painting, he must have deliberately added a pronounced beard. One of the many inconsistencies of the mainstream narrative, as I see it. Highlighting also the central question: Is this face of Christ really worthy of Leonardo? Those who depicted it along with the Mona Lisa, seem to think that yes. But to me, I am afraid, it seems more of a caricature of Christ. Since we are hearing also of Leonardo having used his particular painting techniques of working with his fingertips in the face area, we must again raise the question: If we are looking at the orignal paint layers in the face areas of the painting – is this face really worthy of Leonardo? And here the experts (see consensus of experts, alleged) are actually quite divided. Again: Has Christ been shaved by time? Are there or are there not abrasions in the areas where – it seems – there is no beard today (and where, perhaps, there never was one)?

Boltraffio problem (the):

About hundred years ago connoisseurs suddenly started to think that Leonardo was divine, while Boltraffio was more disgusting. And this connoisseurial tradition did embark to purify the oeuvre catalogue: out with everything Boltraffian – in only with divine Leonardo, as one saw it then.

The Salvator Mundi in question was shown to assorted experts prior to the National Gallery of London’s Leonardo exhibition. It was shown to them along with the London version of the Virgin of the Rocks. And this Virgin, being another ›problem picture‹ now exemplifies exactly what I’d like to call the Boltraffio problem: a reference picture that is as disputed as the picture in question (and the Louvre Abu Dhabi, with the so-called La Belle Ferronière already welcomed another ›problem picture‹, that has a long history of being associated with Boltraffio; see here).

The catalogue of the London exhibition rather arbitrarily decided to regard the Virgin as being by Leonardo alone (and this did not come as a surprise, since London connoisseurs always wished ›their‹ Virgin to be autograph).

But the problem remains: how to tell Boltraffio from Leonardo, if you don’t want to ignore the question alltogether. And what Boltraffio work, what Leonardo work, if you wish to avoid a circular argument, to use as a reference point?

Curls:

Our title graphic features – very maliciously, I know – the hair of the Met’s Girl with Cherries on the right, a painting today attributed to Ambrogio de Predis. John Charles Robinson had sold it, in 1890, to Henry Marquand as a Leonardo (see here). And Robinson is also, we don’t know exactly when, the person who rediscovered the now globally famous Salvator Mundi, which, however Robinson, in his days, had not attributed to Leonardo.

This happened only later, that is: in our days, and some experts refer to the unique rendering of hair, of hand and of the orb.

Or is the rendering of hair, in truth, far from passing as unique, if we look around among the Leonardeschi? This is exactly the question, one of the many questions we address here. See also under ›Finger tips‹.

Distant Relative, A:

If you are looking for a ›distant relative‹ of the Robert Simon Salvator Mundi, my first choice would be the Columbia Museums of Art’s Portrait of a Young Woman with a Scorpion Chain (picture: amazon.com).

Expert’s consensus (alleged):

»Sono di Da Vinci le mani, tutte e due, alcuni riccioli, il globo di cristallo di rocca, fatto di nulla, appunto, con qui frammenti vegetali al suo interno, e i panneggi.« (Pietro C. Marani, Interview in: L’Espresso, 22 November 2017)

Within the group of scholars that, as one does hear, did authenticate the Salvator Mundi, prior to the National Gallery of London’s Leonardo da Vinci exhibition of 2011, we find the opinion that virtually the whole picture (including the face) is supposed to be by Leonardo (Martin Kemp), along with the opinion that only the best parts of it are (or might be) by him. – I don’t seem to be able to regard this as a consensus, I am afraid.

Fingertips (use of):

»The artist known as Giampietrino is one of the most interesting of all the Lombard followers of Leonardo da Vinci, whose refined pictorial technique based of the transparent application of pigment Giampietrino emulated, together with the master’s ›manipulation‹ of the pictorial surface with his fingertips.«

I give this quote (Pietro C. Marani in: The Legacy of Leonardo, Milan 1998, p. 275) just in case you might hear about the (allegedly unique) use of fingertips in paitings attributed to Leonardo (in paintings attributed to Leonardo based on such alleged ›uniqueness‹)

As to ›unique‹ see also here.

(And once again we might also show here the superb Last Supper copy attributed to Giampietrino; note also how drapery is seen through glasses…)

(Picture: Royal Collection/Vimeo)

Globe/global I:

A figure of global imagination Leonardo da Vinci has become, we must say, as we are approaching the 500th year of his death in 2019. But we should not equal Leonardo, the individual that once lived, with his mythical and virtually superhuman counterpart. Let’s look, once more, at how Leonardo, the historical individual looked at the world. And the one way to do that is to look at his most beautiful rendering of planet Earth – his globe.

(Picture: telegraph.co.uk)

Globe/global II:

As the readers of contemporary science fiction from China, that is: as the readership of Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem (part I of the Trisolaris trilogy; 2008) does know, Leonardo da Vinci has a short entrance in chapter 15 of The Three-Body Problem. More precise: a virtual Leonardo has an entrance on the level of a virtual reality computer game. (Does it sound unusual? Don’t worry, Leonardo is wearing his familiar cap as in some well-known depictions of him; his comments on some astrophysical problems, however, are rather scarce and don’t seem to be that profound as one would expect).

For an encyclopedic account on ›Leonardo Vinci and the Far East‹ see my: Leonardo da Vinci im Orient monograph, p. 346ff.

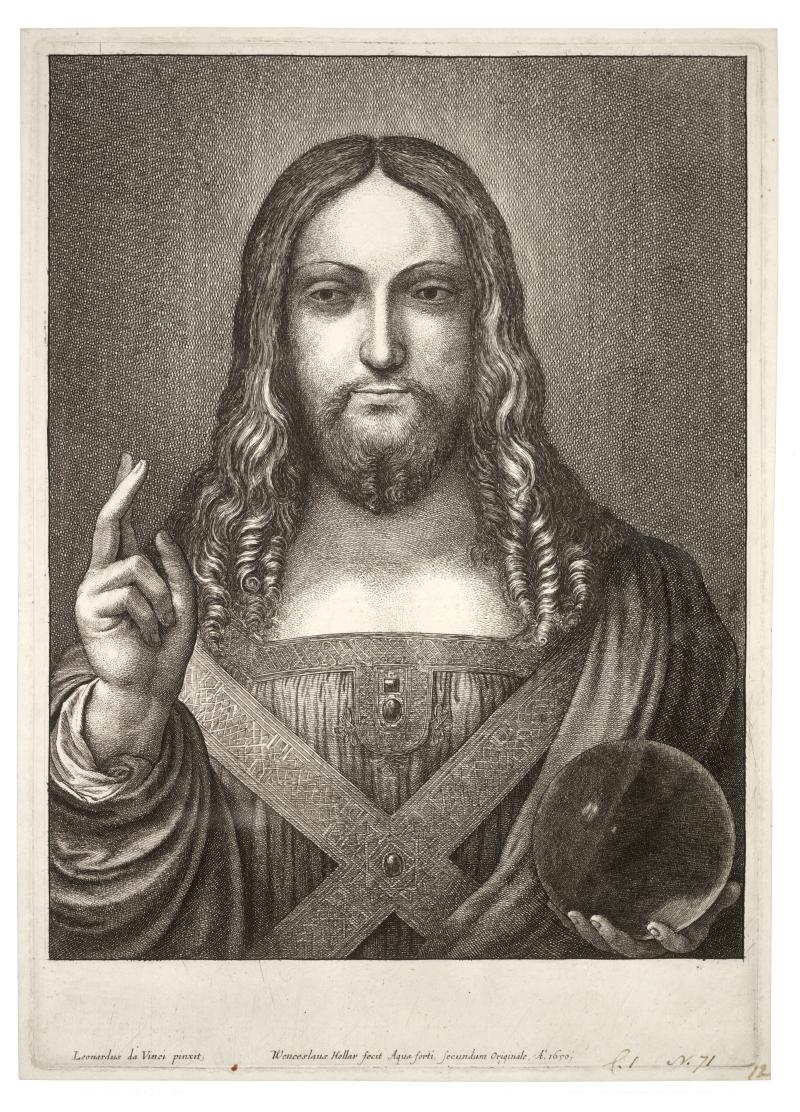

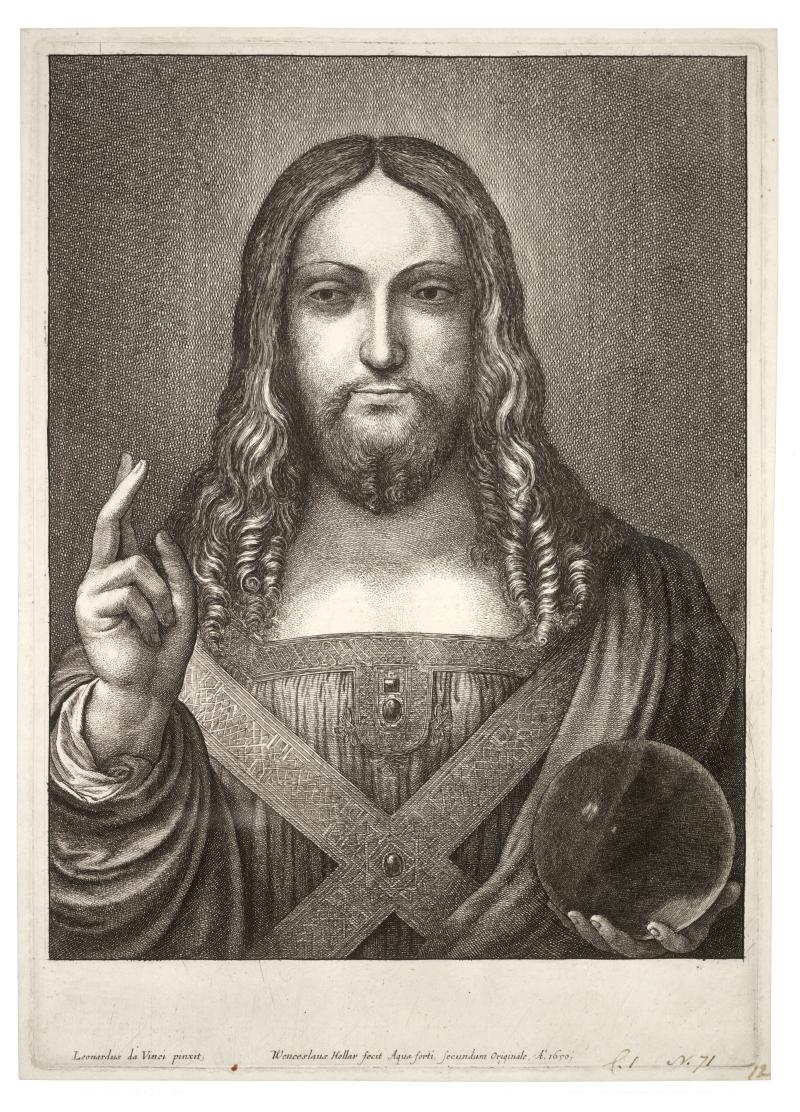

Hollar problem (the):

Wenceslaus Hollar, as we might say, is the crown witness of the Salvator Mundi mainstream narrative: since Hollar provided an etching after a painting that he considered to be by Leonardo da Vinci, it goes, there must be a painting by Leonardo da Vinci.

Today it seems that there is a fixation on that narrative. What, we might ask, if Hollar was wrong, since, yet at his day, there was a confusion between Leonardo and the Leonardeschi? What if the etching he provided, was in fact modelled after an ›only Leonardesque‹ painting. This (this fixation on alleged certainties) I would like to call the Hollar problem. The crown witness to an alternative narrative is Vincenzo Monti (see below).

Hollar in 1650:

In 1650 Hollar did not only provide an etching after a supposed painting by Leonardo, but also an etching after a supposed painting by Giorgione. Since we know that this Giorgione was in a particular Antwerp collection, it seems possible that Hollar did find also the model for his Salvator Mundi etching in that very collection. The mainstream narrative speaks of a Salvator Mundi in the collection of Charles I, but we don’t know for sure if a) Hollar had worked in fact after that ›Royal‹ Salvator Mundi (see above under: Beard) and b) if the painting in the Royal collection is to be identified with ›our‹ Salvator Mundi at all (the provenance still is fragmentary). Brief: We don’t know if the mainstream narrative will pass the test of time at all. For an alternative narrative see under: Monti, Vincenzo.

Hope value:

I have been following the Salvator Mundi controversy from its beginnings, and one of its most interesting details, I found, was the mentioning of the concept of ›hope value‹. Which means that buyers of artworks bet on the possibility that an artwork will be authenticated by experts in the future.

Since technology today allows all kinds of sophisms to argue that Leonardo might have had a hand in a particular painting, we will probably hear a lot more of that concept (which seems to be a conceptualization and further development of the more familiar concept of ›sleepers‹) very soon.

(See also here.)

(Pictures from Mickey Blue Eyes movie)

Inclusions (»frammenti vegetali«):

As you can read above, Pietro C. Marani mentions »frammenti vegetali« inside the orb. – While I can see inclusions, I must say that as yet I cannot see »frammenti vegetali«. (This, as by now, seems to be one of my favourite Salvator Mundi Microstories, as far as here the real details are concerned).

Lapis lazuli

Is the lapis lazuli used for the robe of »extraordinarily fine quality« (Nica Rieppi, as quoted by Time) or »rather coarse and contains particles of quartz« (restorer Dianne Dwyer Modestini; online brochure as provided by Christie’s, p. 71; and Modestini goes on to say: »I have wondered whether it was made by merely crushing the mineral rather than being the product of the elaborate process of extraction used in Tuscany.«)? – See also my list of open questions further below.

Lighting

Note that the Robert Simon Salvator Mundi is lit from the upper left while the Hollar version (allegedly made after this painting) is lit from the upper right.

(Picture: via.lib.harvard.edu)

Monti, Vincenzo

Vincenzo Monti was a librarian of Santa Maria delle Grazie, who did some research into the history of that Milanese cloister and church, famous for Leonardo’s Last Supper (see: here). In fact Monti is the only source that speaks of Leonardo da Vinci having provided a Salvator Mundi painting at all. But Monti does refer to a lunette painting in Santa Maria delle Grazie, a painting that was destroyed in the 17th century.

Our observations are the following: 1) Hardly anybody in the whole Salvator Mundi controversy does seem to know about Vincenzo Monti, that is: about that source. 2) That is, perhaps, little surprising if one stares at the mainstream narrative with Hollar (see: Hollar problem) working after a Salvator Mundi by Leonardo. But Monti gives room to an alternative narrative. Which goes: If Leonardo provided a lunette painting of a Salvator Mundi in Santa Maria delle Grazie, any follower might have started from that, or, if he got access, from workshop materials, for example a cartoon. If a swarm of Salvator Mundi paintings does exist even today (for an overview see here), this is not necessarily the case because Leonardo provided one famous depiction of The Saviour for a European king, that particular depiction, that served as a model for Hollar. It might be much more complicated to provide a ›family tree‹ of all that Salvator Mundi paintings that still exist today, a family tree with various lineages. And one feature to organize such a family tree, one philologically essential feature might the the shape in the drapery that Ludwig H. Heydenreich had baptized the ›Omega-shape‹. It is to be found in the workshop materials that one does partly ascribe to Boltraffio, but surprisingly not in ›our‹ painting where the shape is lacking. Therefore one more inconsistency to be found in the mainstream narrative (see also: Open questions, list of): If ›our‹ painting is supposed to be the one original from which all other versions are derived – why is that particular shape to be found in workshop studies and in other versions, but not in that now globally famous one version?

Open questions (list of)

As to the attribution of the now globally famous Salvator Mundi to Leonardo da Vinci (as by end of April 2018). Here it goes):

– Why does the Christ of the painting show beardless, if it is supposed to be the model for the Hollar etching (some seem to assume that the paint layers of the face are intact, and some don’t)?

– Is exclusive optical knowledge absent or present in the painting?

– Is the lapis lazuli used for the robe of »extraordinarily fine quality« (Nica Rieppi, as quoted by Time) or »rather coarse and contains particles of quartz« (restorer Dianne Dwyer Modestini; online brochure as provided by Christie’s, p. 71; and Modestini goes on to say: »I have wondered whether it was made by merely crushing the mineral rather than being the product of the elaborate process of extraction used in Tuscany.«)?

- Are the pentimenti to be interpreted as more than mere corrections or as mere corrections?

– Can it be excluded that the picture mentioned in the inventories of English Royal collections is the painting of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts?

– Why is the ›omega-shape‹ in the drapery, to be found in the preparatory sketches, lacking in the New York painting, while it does show in other versions, supposedly derived from or later as the New York version?

– How do the experts who do not mention the Vincenzo Monti testimony interpret it?

Optical Knowledge:

If you think that Leonardo da Vinci was the only Renaissance painter with an interest for optical phenomena and sophisticated representations of such, take a look at this detail from the Cena by hardly known Giovanni Agostino da Lodi: a Venetian sense of atmosphere meets a Leonardesque flair for observation (of bread seen through glass).

Pedretti, Carlo:

Doyen of 20th century Leonardo da Vinci scholarship, who passed away early this year (2018). Carlo Pedretti dismissed ›our‹ Salvator Mundi, that is: the Salvator Mundi painting in question here, based, as it seems, on judging by eye. Which means: not by judging the original (in the flesh), but by mere judging one or several photographic reproductions of it.

It is important to mention here that several attributions by Pedretti, over the years, have not found general acclaim, or have even proved to be wrong. And even more important it is to make a general distinction here, that has to do with Pedretti as a Leonardo expert, but also has a more wider bearing. In brief: someone who has studied the labyrinth of Leonardo’s written notes (as Pedretti had for more than half a century), is not necessarily an expert in questions and methods of attributions (its perils and its fallacies).

This said, everyone must form his own opinion as to the matters at stake here. You might stress the fact that Pedretti had virtually supported another Salvator Mundi version in the past, or you might stress the fact (as Christie’s did) that he never did expressively support this very painting. Or you might neglect the fact (as Christie’s did as well) that Pedretti, as I did mention, dismissed the painting here in question in 2011.

What I do recommend here is: do respect the experts in their strenghts (and weaknesses), and don’t listen too much to names, but to their arguments. Do they seem to be plausible and well-founded or not. This is, basically, what counts, and nothing else (and status, in the end, does not count at all on the level of mere scholarship).

(Picture of Louvre Abu Dhabi: wikiemirati)

Persian Gulf (Leonardo da Vinci and the):

Mentioned by Leonardo (as is the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean) in his Codex Leicester (31 r; see again leonardodigitale.com).

For an encyclopedic account on ›Leonardo Vinci and Persia‹ see my: Leonardo da Vinci im Orient monograph, p. 333ff.

Pushkin Museum’s Salvator Mundi, The:

We have been showing the Pushkin Museum’s Salvator Mundi on this website (see here) since 2016. And it was also here, pointing to the already known English Royal provenance of this picture, that the question was raised for the very first time, if the identification of the pictures mentioned in English Royal inventories was correct (this was made more explicit in 2017). Since The Art Newspaper, in their November 2018 piece on the matter, did not acknowledge my work at all (and in the following neither The Times nor any other media around the globe) I have to make clear that the ›rediscovery‹ of the Pushkin Museum’s picture in the context of the Salvator Mundi controversy is my (Dietrich Seybold’s) intellectual property. For everyone with eyes to see the Moscow painting is not only much better preserved than the Robert Simon Salvator Mundi, it is also artistically (and regardless of attribution) the much better painting. At least in our virtual museum, we would place the Robert Simon picture in the basement study collection, while the Pushkin Museum’s painting would belong into the regular collection. We trust that the two pictures will argue this out among themselves in the near future.

The Pushkin painting can be interpreted as a visual reflection on firmness vs. insecurity. The blessing gesture more alluded to than executed, the young Christ serious as a child can be serious and socially insecure at the same time. And there is nothing of that sensibility, which makes the Moscow Salvator Mundi a superb painting, in the Robert Simon picture. (Leonardo da Vinci, by the way, even at the time of #Leonardo500, seems to be admired mainly for skillful naturalism and for special effects; but one should not take this too seriously, because this is really not what art is all about.)

See also: A Salvator Mundi Provenance

Some Salvator Mundi Afterthoughts

Some Salvator Mundi Variations

Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

Leonardeschi Gold Rush

A Salvator Mundi Geography

A Salvator Mundi Atlas

Index of Leonardiana

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Some Salvator Mundi Microstories  |

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS