M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

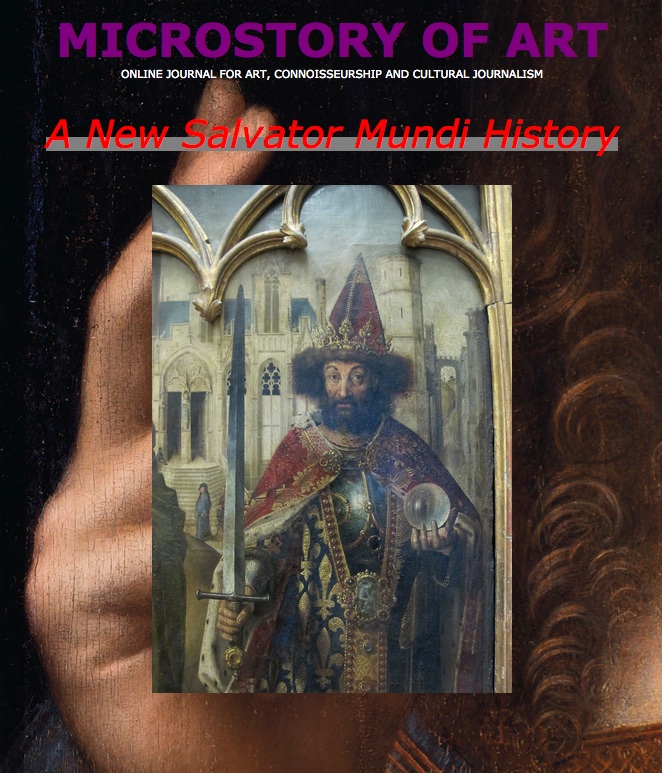

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

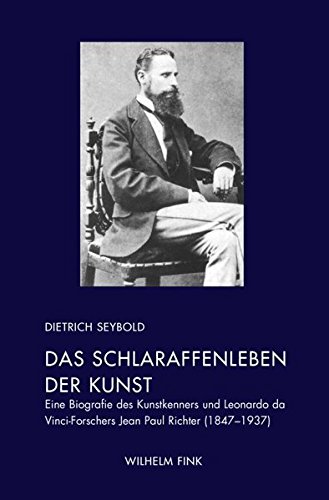

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

SPECIAL EDITION

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM The Fontainebleau Group  |

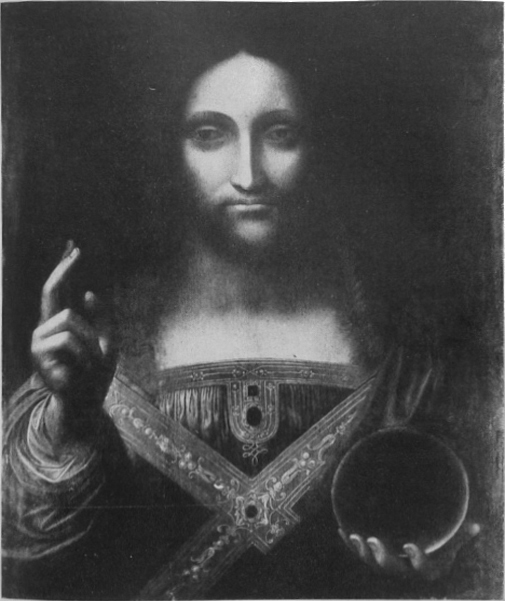

(2.1.2023) The written tradition as to the art collections in Palace of Fontainebleau names Jean Dubois as the author of a copy after a Salvator Mundi painting considered to be by Leonardo da Vinci (see Fagnart 2016). I am attributing, hypothetically, as always, the Salvator Mundi version of the Detroit Institute of Arts (see picture above and below on the left) to Ambroise Dubois or his circle. Ambroise Dubois was the father of Jean, and court painter to Maria de’ Medici (mother of Henrietta Maria, Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland). Below I am going to expound the reasons for this new attribution, the general consequences that follow from it regarding a whole group of Salvator Mundi pictures (which I am calling the Fontainebleau group) and regarding the provenance of the notoriously famous Salvator Mundi version (version Cook), as well as the consequences regarding the history and future of Salvator Mundi studies in general.

[Preliminary note: solid informations on Ambroise Dubois can be found in the Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon (AKL), vol. 30 (this volume published in 2001); the informations provided there I have been using as a general basis; Stanislas Wirth has since then conducted research on this rather neglected painter (the abstract to his thèse de doctorat can be found here; his 2022 monograph has not yet been available to me; bg picture in title: Nathan Hughes Hamilton]

(Picture: Kries)

(Picture: photo.rmn.fr; RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Fontainebleau) / Jean Schormans)

1) What are the reasons for the attribution of the Salvator Mundi version of the Detroit Institute of Arts to Ambroise Dubois or his circle?

I have been following the path that I had sketched out in my Salvator Mundi Geography, which had nothing to do with Jean Dubois.

We know that the Detroit picture (on the left) is painted on a Baltic oak panel that has been dated by means of dendrochronology. By which also the old attribution to Giampietrino (or other Leonardesque painters) has been falsified. My hypothesis had been – due to the apparence of cherub motives in Antwerp Salvator Mundi prints – that the author of the Detroit picture was from Antwerp. While updating my knowledge on the Franco-Flemish painters of the so-called Second School of Fontainebleau, I got to know the painting shown on the right, which is at Fontainebleau (and probably never left it), it is by Antwerp-born Ambroise Dubois, and shows virtually the same type of brooch with pearls – in combination with a cherub motive – as in the Detroit picture (where such brooch appears, in combination with several cherubs, on the stole). My conclusion, due to this (double) match on the level of micro-motives, was that the Detroit picture must be by Ambroise Dubois or his circle (since there is hardly an alternative explanation to this match), which is consistent with the renewed dating of the picture based on dendrochronology.

The person wearing the brooch is Maria de’ Medici, mother of Henrietta Maria (perhaps shown as Minerva, as also Rubens showed her, later). The painter Ambroise Dubois did work for Maria de’ Medici and commemorated, in this certainly official and representative picture, the wedding in proxy of Henry IV and Maria de’ Medici (the official title of the picture seems to be today Allégorie du mariage d'Henri IV et Marie de Médicis).

The attribution seemed all the more reasonable, due to the naming of Jean Dubois, son of Ambroise, as the author of a copy after a Salvator Mundi painting that was thought to be by Leonardo da Vinci. And it should also be mentioned that we know that Ambroise Dubois was commissioned also to paint a copy of the Mona Lisa. Nevertheless Ambroise Dubois seems to be a very neglected painter that only recently, due to the work of Stanislas Wirth, seems to see a rediscovery. The new attribution might add to the renewed interest in this painter.

2) Why Speaking of a Fontainebleau Group?

It is due to a combination of reasons: we see a group of Salvator Mundi pictures of which every picture shows the same type of face, with very characteristic eyes (in shape of mandorla), nose bow and especially mouth with slightly assymmetric beard and very characteristic lower lip (compare for example the Detroit version with the Warsaw version; on the left; and with the Zurich version, on the right). While Detroit has been dated on the basis of dendrochronology, this has also happened with the Warsaw version (formerly attributed to Cesare da Sesto, another attribution which has been falsified), and in addition to that I have shown (and, I think, proven) in my Salvator Mundi Atlas essay that the Zurich version is related with the Detroit version, since virtually identical micro-details in the left-side folds of the garment are appearing in both pictures. All these reasons combined – and again against the background of also the written tradition naming Jean Dubois – allow to speak of a Fontainebleau group, with one picture now being ascribed to one particular author, Ambroise Dubois, who had also been commissioned, as we know, to copy the Mona Lisa.

We have to stay aware that Ambroise Dubois did not work alone. He seems to have been supported by a workshop of Franco-Flemish painters, he was close to other Franco-Flemish Fontainebleau painters, and he did also cooperate with various other painters in Paris (working, in the Louvre, again for Maria de’ Medici).

I am showing here three examples of pictures that I am regarding to be part of the Fontainebleau group; but the group encompasses more (known pictures, as for example the Ex-Versailles version, and the version at Holkham Hall, which is probably a derivative), and possibly even more pictures that might be lost.

3) Is there a reason why the Salvator Mundi might have multiplied at Fontainebleau?

I believe that there might be a simple reason, and this is the reason that Maria de’ Medici may have wanted all her (five) children to get such picture, in view of the religious upbringing, but also in view of later having to represent the Catholic faith abroad, after having been married for political purposes (the best example for that is Henrietta Maria, known for, and being very unpopular due to her Catholicism, in England). The Salvator Mundi iconography, as I have described and discussed recently, has also to be seen as being part of the imagery of the Old European Order, due to representing the metaphysical side of the so-called Divine right of kings. Hence such pictures had not only a spiritual value, but had much to do with religious as well as political instruction of princes and princesses, since it was Political Theology, in which theology as well as political philosophy united.

4) What are the consequences of the attribution as far as the provenance of the notoriously famous Salvator Mundi (version Cook) is concerned?

It seems possible and is, in my view, even likely that the early provenance path that has been, in the last ten years, been associated with version Cook, the notoriously famous Salvator Mundi version, is, in fact, the earlier part of the provenance of the Detroit picture.

If the Detroit version, as is shown here, comes from Fontainebleau, it comes from the place where Henrietta Maria had grown up, and the author of the picture is one of the court painters of her mother. Do we know that she got an original by Leonardo da Vinci? No, we don’t, this is simply an assumption. Is it possible that the original remained at Fontainebleau (probably as the property of the dauphin), and that Henrietta Maria got a copy? Yes, this seems possible, and it seems even likely, because the known provenance of the Detroit picture more or less exactly starts where the known alleged early provenance of version Cook ends. We see – as we might say – the ends of two provenance threads that come very, very close. How close? We see one picture (version Cook, as its defenders claim it to be), at Buckingham House at the end of the 18th century, and we see a musician, the oboist John Parke, buying the Detroit picture somewhat after 1800. But this musician, this oboist had performed in Carlton House. Which means that he had moved in Royal circles. Coincidence? The defenders of version Cook may say, yes. But the provenance of version Cook is one oboist’s performance in Buckingham House away from imploding. Johne Parke might have seen the picture even before Mr. Troward bought it. At any rate: the question has to be raised, if the Troward-Parke picture, in fact, is the Buckingham picture.

What would be the consequence of such implosion? The consequence would be that version Cook, which indeed might have been at Fontainebleau (this is likely, as I also have shown in my book, my New Salvator Mundi History) has no provenance earlier than being in possession of Joseph Hirst in the 19th century.

But this is not necessarily a disaster for defenders of version Cook. It might have been the Luini Head of Christ from the collection of Luigi Calamatta, a picture which was for sale in 19th century London, and one might start to establish a real, solid provenance from there, working backwards. Only: what has been presented to a world audience in the last ten years as the provenance of version Cook, would simply reveal to be a fiction – the result of scholarship that chose to ignore the biographies of other Salvator Mundi pictures, due to a fixation on one picture only, due to all-too-little knowledge, as far as the dangers of attributional hypotheses are concerned, that never should be presented as facts prematurely.

But what about the Hollar etching, defenders of version Cook may ask. Isn’t the Hollar print showing version Cook and is therefore something like evidence that version Cook still was in possession of Henrietta Maria?

My answer to that is: I consider the idea that the Hollar etching shows version Cook as falsified (for the reasons see again my Salvator Mundi Geography; the Hollar etching resembles the Fontainebleau pictures more than version Cook; Hollar, as a matter of fact belongs into that group). It seems much more likely that Hollar saw a picture from the Fontainebleau group, a work by an Franco-Flemish artist, that is, and not by Leonardo. But in my view it is not a version that we know, respectively have. The similarities of version Cook and Hollar may explain by an intermediary version (an unknown version from the Fontainebleau group).

5) What are the consequences as far as the history and the future of Salvator Mundi studies in general are concerned?

The first and most important consequence is the insight that, at Fontainebleau, a new chapter opens, in the history of the Salvator Mundi design that goes back to Leonardo da Vinci. At around 1600 various Franco-Flemish painters, not Italian painters, are reinterpreting the design. And the second important insight might be that, in view of the almost systematic confusion of Italian and Franco-Flemish pictures, in view of myriads of false attributions (false attributions of pictures by Franco-Flemish artists to Italian artists, to the Leonardeschi, primarily), it should be asked why such systematic failure in connoisseurship, in attribution could happen, and it should be asked what the consequences of such systematic failure should and could be.

Selected Literature:

Laure Fagnart, L’appartement des bains et le cabinet des peintures du château de Fontainebleau sous le règne d’Henri IV,

in: Colette Nativel (ed.), Henri IV. Art et pouvoir, Tours 2016, p. 53-65

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS