M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

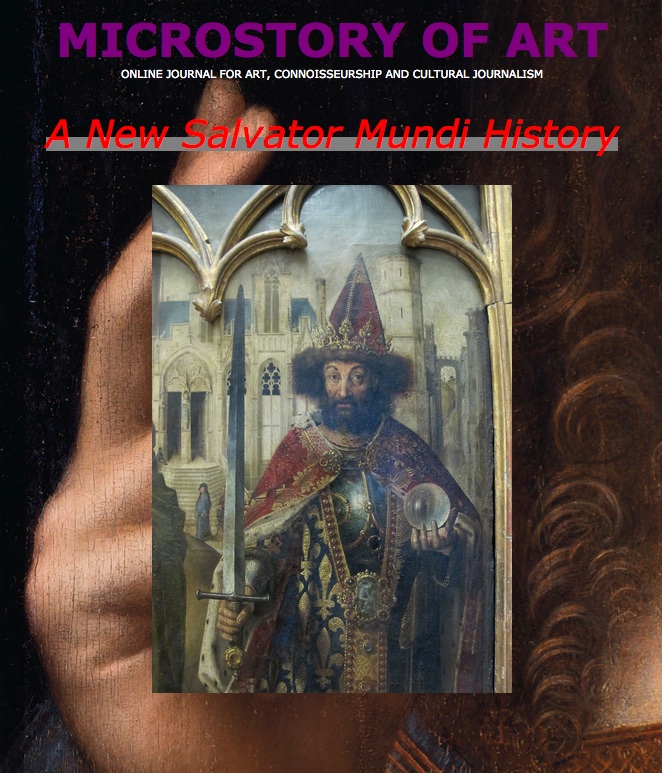

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

Dedicated to 1990s Painting

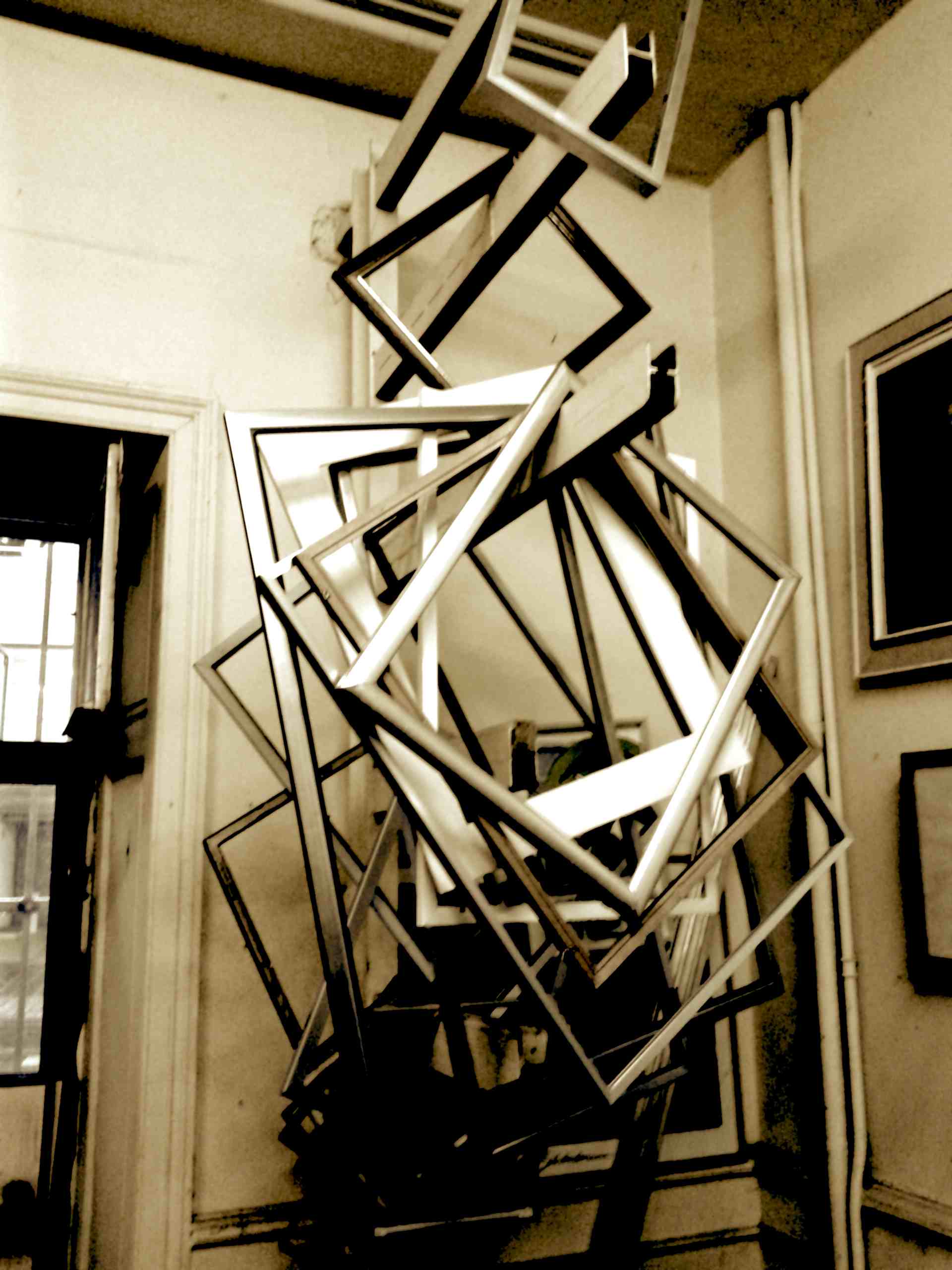

(Picture: Sailko; Studio of Francis Bacon who died in 1992)

How Painting Survived the 1990s

(20.-22.3.2023) When we look back at fifty years of painting after the death of Picasso (in 1973), there was one decade, the 1990s, when painting seemed to be in serious trouble, brief: in crisis. Not everyone would probably agree to that, because, of course, there was painting; and perhaps, one day, someone will say that, during the 1990s, painting was at its best, perhaps just because it was struggling (and not necessarily thriving). But it is not that difficult to assemble voices stating that, yes, the 1990s were rather hostile to painting. Film, video, photography was dominant, and, for various reasons that are interesting to look at also, painting was struggling and not generally thriving. But perhaps we should rather say, no, painting was not struggling, but during the 1990s it seemed not to be that attractive to paint, and the decade (or at least its first half) did rather not encourage young artists to paint (rather explaining to them why one should not do so). But some did, and it is tempting to imagine an exhibition that focusses on these artists, on their struggles, embedding their stories into a general history of painting in the 1990s, which, of course, could also be written from numerous angles. Whatever might be the truth of ›how and why painting survived the 1990s‹ – it is worthwhile to ask these questions, that, perhaps will lead us to a rediscovery of 1990s painting, of painting discourses, be such discourses subtle and intelligent, or rather boring and stupid. So let’s look at a few examples of ›how painting survived the 1990s‹, which is not meant to replace an exhibition on that topic, but to assemble some ideas on how such exhibition could be made.

One) Surviving Picasso

Since we have chosen the ›fifty years since Picasso’s death perspective‹, let’s briefly review a few 1990s ›Picasso dates‹. The throne of painting was empty, but invisibly Picasso still sat on that throne, also during the 1990s. But in the wake of the books by Françoise Gilot (1965) and Arianna Stassinopoulos Huffington (1988) a very critical discourse on Picasso was in the making or had already been established, a discourse that culminated in the 1996 movie on Picasso, which was called Surviving Picasso, a film (after the book by Stassinopoulos Huffington, which, on its part, was also based on interviews with Gilot), a film which – for legal reasons – could not actually show works by Picasso, which means that the film showed a version of the man, the colossus of painting, and hence – on some level – it showed, or better: established, reaffirmed, the throne of a colossus, without being able to actually show works of art by the artist. In other words: Picasso was there, but if he was an artistic influence during the 1990s was another matter. He was there, due to his status having been established in his lifetime, and after his death, he was there as a towering figure, representing the faith in art, painting and in the ability of artists of renewing painting, while, during the 1990s, film, video, photography was dominating.

And it is perhaps symptomatic for the decade that the presence of Picasso was intensely felt, without Picasso’s art being a direct influence. But chosing to be a painter meant to chose a role with which Picasso was still being identified.

One could avoid the direct comparison – by chosing a paradigm of painting with which Picasso was not associated at all (gestural painting; abstract painting) or by ironizing the whole approach (as Kippenberger did, in 1996, shortly before he died, in 1997, with his Bilder, die Picasso nicht mehr malen konnte).

Another towering figure, Francis Bacon, had died in 1992. And, as can be seen in the picture above, his studio got preserved as a lieu de mémoire. Which might, perhaps, be seen as an indication that, no matter what postmodern discourses said as to the end (death; but also: goal) of (gestural) painting, a basic faith in painting still seemed to be intact, even if a sceptic might add here: due to a cult of artists that, again, might have had much to do with the cult, or myth of Picasso, the colossus. (And perhaps this basic faith in the importance of painting and its cultural value did also show in the notorious fuss about an important cycle of works by Gerhard Richter being sold to the United States in 1995).

Two) Being an Apprentice, Being a Sponge: Hamburg

In hindsight things might look very differently, but this is also why doing history makes sense: it refreshes our views on our own lives. As someone who grew up with 1980s radio (on some level I have never turned off radio during the 1980s), I had not understood at the time that 1980s painting (for which I had not developed a particular interest) and 1980s pop music actually have to be seen as a whole, as being part of complex urban scenes and cultural configurations, in which also the more intellectually ambitious pop discourses had played an important role (but I never read Spex). Things might have dramatically changed with the year of 1989, and personally, when following the history of 1990s painting, I find the case of Daniel Richter, who chose to become an art student only in the early 1990s and was accepted as a student in Hamburg, particularly interesting. I would pick him as my Cicerone, while others might pick other biographies or artists, when reviewing 1990s painting and its struggles (Isabelle Graw who seems to favour Jutta Koether, says also that, at the time, at c. 1991, no one was able to value her importance as an artist, a hindsight view this is as well, but I am chosing another example). One might also start a review of 1990s painting with saying that the magazine Frieze had a Damian Hirst butterfly painting featured in the first issue and, yes, in my view the art scene of the 1990s actually tended to establish art on a level of pop radio, which I mean not in a favourable sense, but let’s focus on Daniel Richter, who seems only to have painted abstractions until his figurative turn of 1999.

Daniel Richter studied at Hamburg (Prof. Werner Büttner) from 1991 to 1995. 1992 was the year of his thirtieth birthday, and in 1993 (the year in which Neo Rauch found the first paintings that he accepted as valid and relevant), in 1993, it is said that, at the Hochschule für bildende Kunst at Hamburg (more precisely: at the automat for beer) Daniel Richter vehemently advocated abtract painting (see Saehrendt 2010; the author was another student then). Because social critique could not expressed anymore by means of figurative painting.

In hindsight it might look that Richter, then, was still to find himself. In 1995 and after that, he had solo exhibitions, and during that time he might also have been under the impression of the so-called ›Tate disaster‹ of 1994, another event of the 1990s, a disaster that R B Kitaj experienced (who was shocked and hurt by devastating critique; this is a point of reference in Richter/Putz 2020), but it depends upon how history is (re-)contructed. If the post-1999 Richter gives us a measure, one might say that Richter, in the 1990s, was on the one hand a beginner and a thirty-something-old student, and that, on some level and in the second half of the decade dominated by the new media, he did still work under cover (as an abstract painter). In 1999, with his figurative turn, he might have left that cover. At the end of the decade; and perhaps after digesting what had happened in that decade (and before). The cosmos, for which Richter is known, includes much, and I am inclined to suggest a wide perspective: that cosmos includes the music to which Richter is listening while painting, it includes the conversation his art is instigating (and Richter seems to be, judging by interviews, an interesting conversationalist). It includes a view on the views of new media art (the ways of looking through a camera or other optical devices, and it includes, of course, content, tradition, atmospheres, references to literature, cheap gags and so on. It is a productive cosmos, and all of it might be the result of what Richter did and digested. During the 1990s. Thus, even if Daniel Richter has become widely known after 1999, it is actually (also and perhaps primarily) a 1980s and 1990s cosmos, that further developed in the context of the post-2000 painting boom. And only one did see Richter bloom after the end of the decade of the 1990s, in which Richter perhaps experimented and thus acted as a sort of sponge. Absorbing everything. That later made his cosmos. The story of 1990s can be read, briefly, in two ways, as a success story with a post-1999 climax; or as a story of vulnerabilities, incertainties, changes of direction. And everything is important here: the beer automat, the Tate disaster, the new media, perhaps the optimism of gallerists, and, yes, finally also the success. This is, basically, how painting survived the 1990s (and the model that is given by Richter, could be compared with other cases of male and female painters, in the decade of the 1990s).

Three) Frankfurt, and, of course, Leipzig

Jean-Christophe Ammann is one of the voices stating that the decade of the 1990s was dominated by the new media and not by painting. The decade was also influenced by himself, and acting as the director of the Frankfurt Museum für Moderne Kunst, his doing is well documented, and it is interesting to see how Ammann, as someone who appreciated the wonderful and complex tradition of painting, also helped painting to survive the 1990s, and this in two ways: by analysing for example how the complex tradition of painting survived in, or better, fuelled the photography of a Jeff Wall (for example in his Storyteller, also exhibited in Frankfurt). And by including painting, and also new painting, in what he did in the Frankfurt museum (where the collection of 1960s art was reconfigurated, regularly, and also more contemporary art could be shown in the context of such reconfigurations). Cecilia Edefalk was shown for example, Marlene Dumas, and Miriam Cahn. Painting did survive, thus, on the one hand in the new media (and in the discourses Ammann helped to establish), and also, more physically, in places where painting was given space, because a sensitive and curious museum’s director was sensitive to some qualities of contemporary painting, as well as to the vulnerabilities of painting in the cultural atmosphere of the 1990s.

Being vulnerable – this can be seen as a strengh or as a weakness. Let’s see it as a quality here: the title that I would suggest for an exhibition of 1990s painting would be: ›Painting and its Vulnerabilities – the Decade of the 1990s‹, and certainly space would have to be given to the stories of Arno Rink and to that of Neo Rauch. It would also focus on self-confidence on the one hand, and on chronic self-doubts on the other (two further qualities, as I would stress). Neo Rauch who had been studying with Arno Rink earlier, in the 1990s, and after also having studied with Bernhard Heisig, was Rink’s assistant. As said he seems to have found his cosmos – I am deliberately choosing that word that also Rauch himself is using – in the early nineties. Neo Rauch is on record stating that he had had been wanting to become a painter always, a painter, not an artist, and that being a painter, on some level, was a way to avoid growing up. Such stubbornness does make one vulnerable, can make one vulnerable, under certain conditions, but it is the stubbornness that also, along with beer automat and so on, helped painting to survive the 1990s. And for these things, for paintings having grown out of such stubbornness, or games of stubbornness that, with the painter actually hardly knowing why and how, result in pictures, for these phenomena 1990s painting gives us many examples. Such works are memorable, and certainly more memorable than certain discourses on painting dedicated to the end of painting. Which are memorable also, but rather in terms of being a thorn, in terms of hurting, and not in terms of actually ending painting, and in the end: in terms of asking for the end (=the goal) of painting.

Further Reading:

Christian Saehrendt, Seltsame Symbole – latente Bedrohungen, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung No. 185 (12 August 2010), p. 45;

Peter Richter / Hanna Putz, Strich für Strich, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin No. 26 (26 June 2020), pp. 10-25;

Jean-Christophe Ammann, Bei näherer Betrachtung. Zeitgenössische Kunst verstehen und deuten, Frankfurt 2007; [along with] Andreas Bee (ed.), Zehn Jahre Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main, Cologne [2003];

and see: Der Maler Arno Rink – Wegbereiter der Leipziger Schule, Nicola Graef (dir.), 2018 [documentary aired on ARTE]; Neo Rauch – ein deutscher Maler, Rudij Bergmann (dir.), 2007

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS