M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

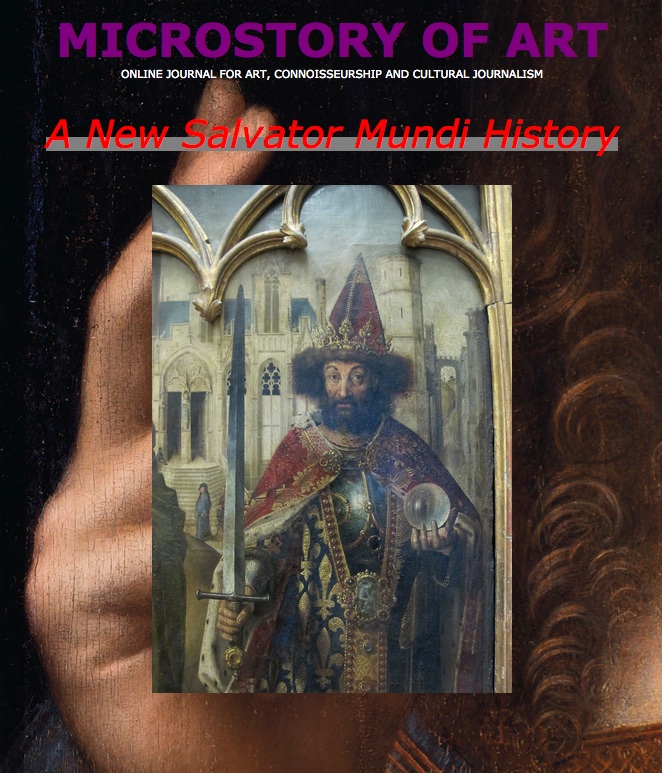

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

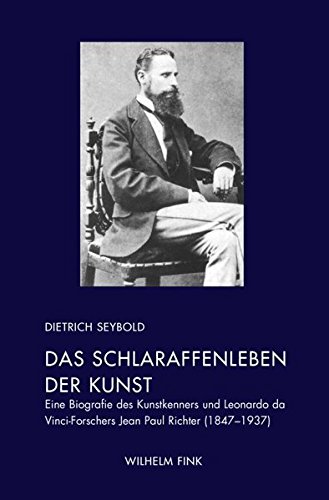

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

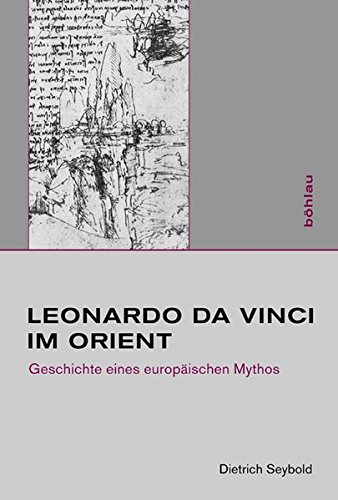

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

Spending a September with Morelli at Lake Como or: Excursions into the Lombardic Pre-March Era  (Picture: villacarlotta.it) |

This introductory visual essay is meant to set the scene and to introduce some of the main characters. Next to the – in 1846 – 30-year-old Giovanni Morelli, we see two of the three Frizzoni brothers, Giovanni and Federico Frizzoni, his closest friends from Bergamo, but also his fatherly friend: German professor Johann Georg Veit Engelhardt, who did spent the September of 1846 with Morelli at Lake Como and did, with his reports, provide us with some microhistorical insights (see Engelhardt 1847). And we hear also of his two other, but absent mentors, Florentine nobleman and historian Gino Capponi, and Munich-based artist Bonaventura Genelli.

ONE) FROM LECCO VIA VARENNA TO BELLAGIO

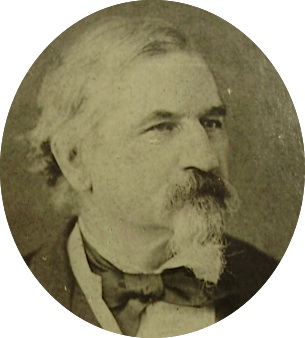

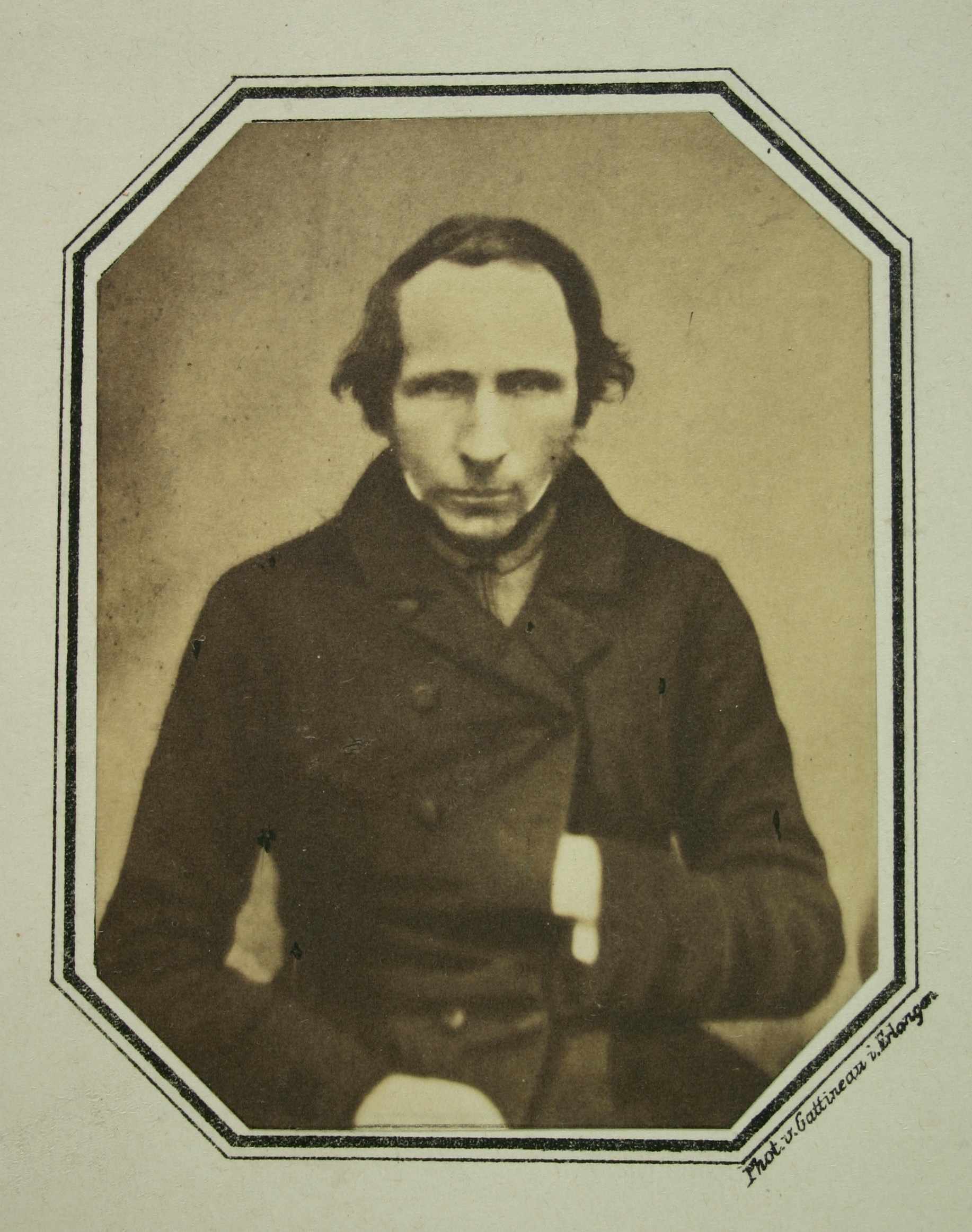

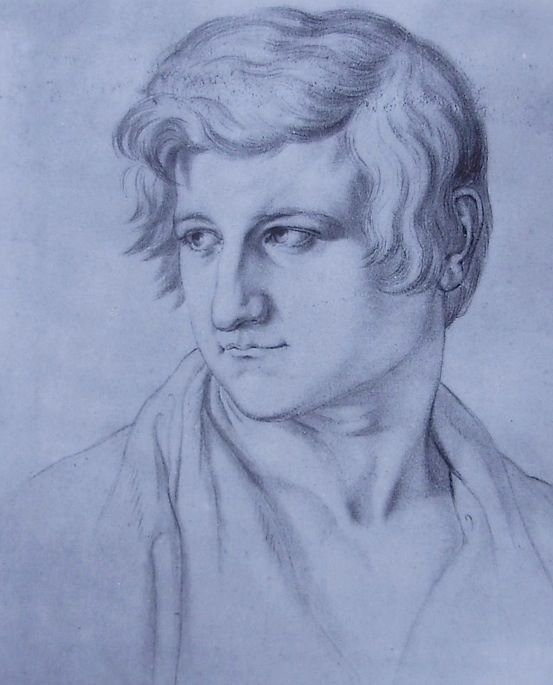

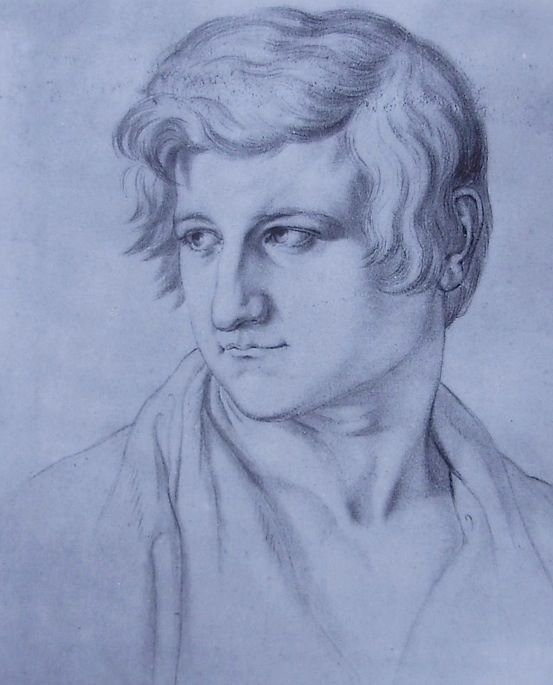

Johann Georg Veit Engelhardt (1791-1855)

(source: Universitätsbibliothek Erlangen-Nürnberg;

published with kind permission of the library)

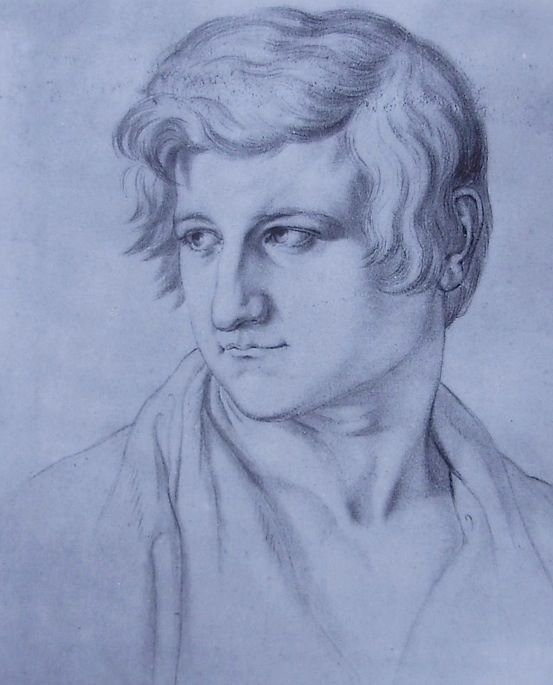

Giovanni Morelli as seen

by Bonaventura Genelli in 1837

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 114)

The two travellers had just taken a meal, consisting of a soup with macaroni, of chops and fish and, not to forget: of red wine from the region, when entering a carriage that was going to take them from Lecco, at the southeastern tip of Lake Como, to Varenna, where the two were planning to enter a boat that would take them to Bellagio. It was a day in September of 1846, and the two travellers were 30-year-old Giovanni Morelli and his fatherly friend from the North, 54-year-old German professor Johann Georg Veit Engelhardt, a professor of theology at Erlangen who was specialized in the history of the church. The two were coming from Bergamo, and Engelhardt was going to spent a whole month at Lake Como. His travel companion, and more than that: his guide was his young friend Giovanni Morelli who had settled, some years earlier, in this region, and was going to provide Engelhardt with some insights, not only as to the country and its people, but also as to his own personal life.(1)

(Map: Markus Bernet)

It may have been early in the afternoon of this day in September, that the two passengers now entered a carriage. And possibly the impressions of Lecco were still lingering in their minds, when entering the landscape scenario of famous Lake Como.

A fair was held on this particular day at Lecco, the city of their departure, and after our two passengers had finished their meal at an inn, they had, from the first floor, listened yet to a band of musicians, playing on the street. A band consisting of four, a bass trombone, two clarinets and a double bass, playing and singing a murder ballad (›Moritat‹) that, possibly, was now echoing in the minds of our two travellers, being on their way to Varenna. The text of that ballad had also been offered for sale to the people listening or passing by.

On a road that only recently had been finished, our two travellers were now heading towards Varenna, on a road above the right lakeside, partly being very narrow, and partly leading also through galleries, through tunnels that only recently had been driven into the rocks. And after a while, after having let first impressions of Lake Como sink in into his mind, Engelhardt, the professor, now began to muse about a certain problem, an issue that certainly rather seemed to be of a very delicate nature to him.

Not about the murder ballad Engelhardt was musing, but about the fact that famous Lake Como, the much sung about and highly praised Lake Como seemed, as far as Engelhardt was concerned, not exactly meet the high expectations raised by so much praise. The lake, in a word, seemed not exactly justify high expectations that one was entitled to have concerning this particular lake, high expectations as to the beauty of that lake and its surrounding landscape.

And how to tell this, how to tell this rather sobering fact to friend Morelli? This was, in short, the delicate problem that Engelhardt, the lake to one side, a wall of rocks to the other, was musing about.

›I thought of the peaceful serene mirror of strung-out Vättern with its lovely island of Wistingsöe and the romantic backdrop of its sudden and yet unexplained currents, the serene Jönköping being situated on its Southern beginning, the tiny cities and sites, being of historical significance, on its right shore; I thought of the Mälaren, surrounded by bushes, to which the magnificent Stockholm grants such a splendid observation point, of the Lake of Zurich with its abundance as to culture, buildings of leisure and fertility, of the lakes in close-by Bavaria, the morning-fresh beauty, the evening mildness, full of premonitions, of Lake Starnberg with the background of his steep Alps, of lovely Ammersee (I thought), being situated behind Murnau like a gem within a wreath of lovely hills, of the serious meaningfulness of the Bartholomäussee with its mysterious drain, of the open vasteness of the Chiemsee and of a many other lovely image of a lake. This all was meant to be surpassed here.‹

························································································································································································································

»Ich dachte an den friedlichen heitern Spiegel des langgestreckten Wettern mit seiner lieblichen Insel Wistingsöe und dem romantischen Hintergrunde seiner plötzlichen noch unerklärten Ströme, das heitere Jönköping an seinem südlichen Anfang, die historisch bedeutenden Städtchen und Orte an seinem rechten Ufer; ich dachte an den umbüschten Mälaren, dem die prächtige Stockholm einen so glänzenden Aussichtspunkt gewährt, an den Zürchersee mit seiner Überfülle von Kultur, Lustgebäuden und Fruchtbarkeit, an die Seen im nahen Bayernlande, die morgenfrische Schönheit, die abendliche ahnungsreiche Milde des Sees von Starnberg mit dem Hintergrunde seiner steilen Alpen, an den herzigen Ammersee, der hinter Murnau wie ein Juwel im Kranze lieblicher Hügel liegt, an die ernste Bedeutsamkeit des Bartholomäussees mit seinem rätselhaften Abfluss, an die offene heitere Weite des Chiemsees und an so manches andere liebliche Seebild. Das alles sollte hier übertroffen werden.«(2)

But since it could’t be helped, Engelhardt finally decided to confront his fellow traveller, 30-year-old Giovanni Morelli, with the sober fact that Lake Como had not yet surpassed all this, certainly being aware that Morelli was in the habit of referring to Lake Como as of the ›King of all freshwaters‹.(3)

It could’t be helped, since Morelli trusted Engelhardt like a father, whilst Engelhardt, on his part, knew, that Morelli, the passionate Lombardic patriot was inclined to hot-tempered outbursts, in case his sensitive pride had been insulted (or the country and its people of which Morelli was deeply proud of). Just as Morelli could be exuberant, if feeling that he had to give vent to his feeling of joy, he could feel compelled to give vent to his anger and rage. And it was not advisable, at least not in Morelli’s presence, to refer to Lombardy as being ›prosaic‹ and to look ›like a cabbage garden‹ (a German writer, apparently, had been found guilty of that particular crime),(4) because hot-tempered outbursts could be arise from this. And as far as the Austrian rule over Lombardy was concerned (Lombardy being a part of the Austrian-ruled Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia) Giovanni Morelli was simply and literally an angry young man of his day, a young man who did hate nothing more than the foreign rule, and it could happen that Morelli, in his patriotic pride, worked himself into a state of excitation and even did terminate friendships due to a trifling cause (even if he was to painfully regret it, only a little later, if his anger had died down).(5)

And it was not advisable either, by the way, to direct the conversation towards the recently and (and under Austrian guidance) constructed and finished road, on which our two travellers presently were heading to Varenna. Namely the question if the Austrian rule had (possibly) brought also something good, or if Habsburgian Austria had in fact neglected necessary improvement of infrastructure, was one of these sensitive questions, better not to be discussed while a hot-tempered Lombardic patriot was present.(6) And even less, if one just headed to Varenna on one particular road that also was of the highest importance as to the mobility of the Austrian military and could serve as a link between Lecco and the Valtellina, and thereby as a link to the army road that led to the Tyrol.

This all beside the fact that on that particular road, one could also get to Varenna where, as our two travellers were planning, one could enter a boat that was to take one to Bellagio, the proverbial pearl of Lake Como.

F. Mojo, La Galleria di Varenna (1843) (source: Volpi et al. (eds.) 2006, p. VI)

But Engelhardt and Morelli were on such familiar and friendly terms that hot-tempered outburst were not necessarily to be expected, even if it was about the ›King of all freshwaters‹. They had known each other for nine years now, since they had first met in the fall of 1837, when Morelli, who had graduaded in Munich, continued his studies with a short stay at Erlangen, where Engelhardt held his professorship. The originally planned three weeks had turned into seven months, also due to the bonds of friendship between the elder and the younger, being a result of this stay.(7) And Engelhardt was a quiet, modest and balanced nature who was entitled to discuss delicate issues with Morelli, and be it Lake Como not exactly meeting high expectations as regards to that lake. Engelhardt had also been a friend to yet another sensitive young man, namely to poet August Graf Platen von Hallermünde (who though, in 1835, had died), and Morelli’s answer to his fatherly friend’s confession, was indeed calm and also judicious. And foreseeing that his friend’s judgment most likely was to change during the next couples of weeks, and perhaps also in joyful anticipation of seeing such a change of mind in his friend any time soon, but most certainly in generally joyful anticipation of a longer stay at Lake Como with his dear friend Engelhardt (and to experiencing a beloved country anew and with a friend and therefore to love the country and its people only more), Morelli answered, as Engelhardt did recall it later:

›Lake Como, he had said, is the kind of lake that, to be able to appreciate it, one has to become acquainted with it, to settle into it.‹

························································································································································································································

»Der Comersee, hatte er gesagt, ist von der Art, dass man mit ihm vertraut werden, dass man sich in ihn einleben muss, um ihn würdigen zu können.«(8)

*

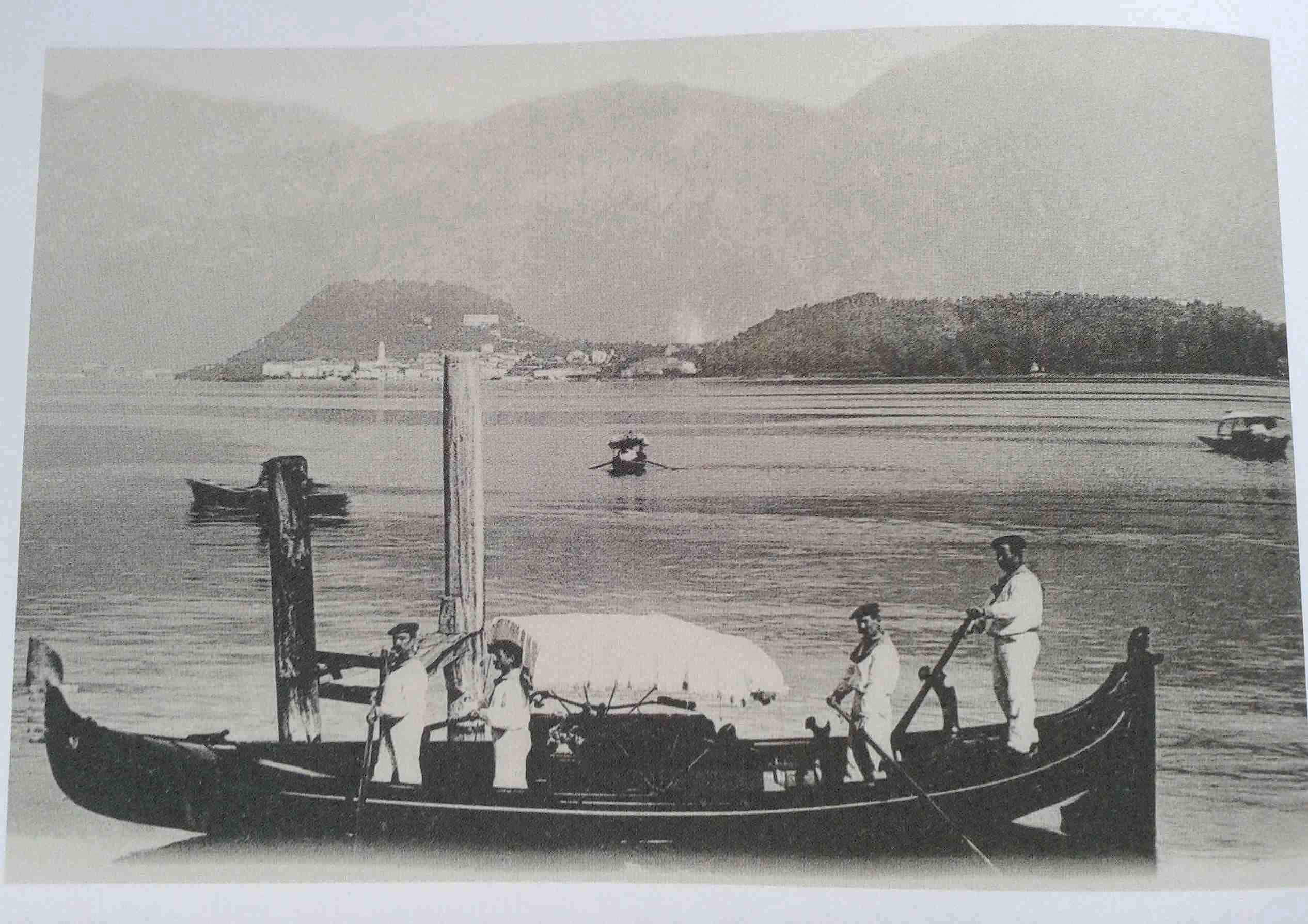

(Picture: Joyborg)

TWO) SOME CLUES AS TO A MORELLIAN GEOGRAPHY AT LAKE COMO

If close friends of Morelli memorialized themselves by erecting impressive buildings at splendid locations – Morelli himself preferred more modest lodgings. According to his nature, which tended to see human pretention rather from its comical side, he decidedly preferred to settle in half-disguised, but functional lodgings that were situated rather somewhat beside the main roads. And if one thing was clear, then it was that mimicry, for Morelli, was more important than splendor.

But he also used to be a guest, a most welcome guest, as one has to add, in the more exquisite, more glamorous lodgings and villas of his many friends. And this also, and particularly at Lake Como.

Some of his many friends were well-to-do, but some had to be referred to as being extraordinarily wealthy. While Morelli, in 1846, was well-to-do in a rather modest way, being the owner of a small manor that was located at one of the satellite lakes of famous Lake Como, namely the Lago di Pusiano, situated in the so-called Brianza, the landscape that stretches between the North Italian lakes and Milan. His manor was located at San Fermo (also: Sanfermo), a small village near Pusiano.(9)

While nothing probably has remained of Morelli’s then lodging – the central part of the today Grand Hotel Villa Serbelloni at Bellagio goes back to the villa that one of Morelli’s best friends from youth, namely Federico Frizzoni, was to build to himself on the tip of the Bellagio promontory. And Federico, or Friedrich (Fritz), as Morelli had it also, was probably to chose that splendid site, one of most exquisite sites for a hotel in the whole world, only because it had eluded him to buy Villa Arconati (also named Villa Balbianello) on the Western shore of the lake, and also being situated rather close to Bellagio (we will come back later to that site).(10)

The Frizzoni family, the two Frizzoni brothers Giovanni and Federico, that have to be considered as Morelli’s best friends (he was less close to the third and eldest brother Antonio), this was the one family in his circle of friends that was not only to be considered as well-to-do, but simply as being rich. And the wealth of the Frizzoni family that allowed members of the family to memorialize themselves, not only by means of erecting buildings, but also by means of multifarious acts of philantropy, had been assembled, how could it be otherwise?, by being active, by being most successful in the silk trade.(11)

The today Grand Hotel is not to be confused with the so-called Villa Serbelloni, situated on the wooded hill above the actual center of Bellagio, and being surrounded by a park. But this villa has also to be seen as a central site within a Morellian geography at Lake Como. But it has turned into being such a site only in the 20th century.

The villa houses today (and since 1959) the Bellagio Center of the Rockefeller Foundation, a charitable foundation, founded in 1913. The Bellagio Center does organize and host international conferences and does welcome scholars and intellectuals from all over the world, and in 1977 it had hosted a conference on the subject of »The Humanities and Social Thought«: And it had been on this very conference that, for the very first time, a paper, an essay had been presented that has be be considered not only being a classic, but also as being crucial to the fortuna critica of Giovanni Morelli, the art connoisseur of the 19th century, in the 20th century and beyond.

Carlo Ginzburg, the Italian historian, at Villa Serbelloni, at the Bellagio Center of the Rockefeller Foundation, had presented, in 1977, the first version of his subsequently widely spread essay Clues.(12) And to this essay, without any doubt, Giovanni Morelli does, in the main place, owe a certain posthumous fame within the Humanities, a posthumous reputation, since Ginzburg had, in this very essay, defined a troika of 19th century figures, consisting of Giovanni Morelli, Sherlock Holmes and Sigmund Freud.

A view on the promontory with Bellagio

and also (in the background) with Taronico

(picture: cercaristoranti.it)

Becoming aware of a Morellian geography at Lake Como, we may even imagine that Giovanni Morelli himself was, many times, glancing over at Villa Serbelloni from his actual, more modest and half-disguised later own lodging at Lake Como, namely at the village of Taronico, also situated on the promontory, above and somewhat behind Bellagio. To settle at Taronico (which Morelli did only in the 1850s), one might say, meant to be able to survey the left arm of Lake Como on the left and the right arm on the right, as if from the position of a rider, the promontory thought being a long saddle.(13)

And we may now even imagine that, being half-hidden in his modest lodging, and perhaps at first not being all-too amused about Morellian geography being revealed here, we still may imagine Morelli looking down on us, and being, all in all, amused about what he did see.

If observing, not the least, the institutional landscape that has settled at Lake Como, with the Rockefeller Foundation, for example, by which presence Morelli certainly would have been reminded of a satirical piece that he once had written (but had never published), a piece that had had a Mr. Johnson, a ›Yankee from Chicago‹, contemplating the late 19th century European art world, and this Mr. Johnson (of course another alias of Morelli himself) also advising his fellow-Americans as to art affairs.(14)

And Morelli would have become aware, with mixed feelings, as we may imagine, of a »Deutsch-italienisches Zentrum für europäische Exzellenz« at Menaggio, since not only himself was someone trying to unite Italian and German culture in himself, but he had actually been someone explicitly demanding narrow political cooperation between Germany and Italy in 1848, and had become deeply disappointed by German politics tending to ignore such (idealistic) ideas.

Resulting with that to to all things German, at least for many years, Morelli was to become most touchy. Despite, or just because of his once wanting to be a cultural transmitter, bringing German culture to Italy (with mixed success). And in general Giovanni Morelli had cherished a love-hate-relationship with all things German throughout his whole life, and particularly with all things German associated with art history and connoisseurship, and being present on Italian grounds.(15)

Our two travellers, having arrived now at Bellagio, and by boat, are right now just taking coffee at the center of Bellagio. But according to their plan, Engelhardt was now to be introduced to Morelli's friends. Which meant that Engelhardt had to be taken to the neighbouring village of San Giovanni. And Engelhardt had to be shown how Morelli’s best friends, how the Frizzoni’s lived. In 1846 Friedrich Frizzoni had not yet built his villa at the tip of the promontory. But Giovanni (Johann) had settled in a villa at San Giovanni. And to this lodging our two travellers were now heading to:

(Picture: villacrella.com)

›After we had had coffee, we went to visit friends in a neighboring villa. We strolled down the hill, on which elevation Villa Serbelloni shows itself all around, on a broad footway which is kept clean, leaving Villa Giulia on the left, to which one ascends many stairs on a broad stairway, made from stones, and leaving elegant and graceful Villa Melzi on the right, with its serene garden at the shores of the lake. The footway then led over the footbridge across a mountain stream first, which brings much coarse gravel into the lake, then between high walls through the narrow alley of the village of San Giovanni, then between gardens, and towards the foot of the hill, on which the villa, our aim, was situated. A pergola, still preserving leftovers of an abundance of grapes, which had been the splendor of it, a week earlier, led up to the hill. We stepped out to a large, broad terrace; having the large house on our left. On the terrace were several children, devoted to their playing; but when catching sight of my companion they stopped their playing, and, with cries of joy, they were darting at us, flinging their arms around the well-known friend of the house’s neck. Soon the ladies of the house neared, and the man of the house [Giovanni Frizzoni], and for the first time I found myself in one of those much-praised Italian villas, within the circle of the owners.‹

·····················································································································································

»Nachdem wir Kaffee getrunken hatten, gingen wir Freunde in einer benachbarten Villa aufzusuchen. Wir schlenderten den Hügel hinunter, von dessen Höhe herab die Villa Serbelloni sich weithin sichtbar macht, auf breitem reingehaltenen Fusswege, die grosse Villa Giulia, zu der man auf breiter Steintreppe viele Stufen hinaufsteigt, links, die elegante zierliche Villa Melzi mit ihrem heitern Garten am See rechts liegen lassend. Der Fussweg führte dann erst über den Steg eines Bergbaches, der eine Masse Steingerölles in den See führt, dann zwischen hohen Mauern hindurch in eine enge Gasse des Dorfes San Giovanni, hierauf zwischen Gärten durch an den Fuss des Hügels, auf welchem die Villa, die unser Ziel war, gelegen ist. Eine Pergola, die noch Reste von der Traubenfülle bewahrte, mit welcher sie die Woche vorher geprangt hatte, führte uns den Hügel hinan. Wir traten auf eine weite freie Terasse heraus; das grosse Wohnhaus stand uns zur Linken. Auf der Terrasse waren einige Kinder im eifrigen Spiele begriffen; als sie aber meinen Begleiter ersahen, liessen sie das Spiel und flogen mit Freudengeschrei uns entgegen und dem alten wohlbekannten Hausfreund an den Hals. Bald kamen die Damen des Hauses, es kam der Hausherr heran, und ich fand mich zum erstenmale auf einer jener vielgerühmten italienischen Villen im Kreise der Besitzer.«(16)

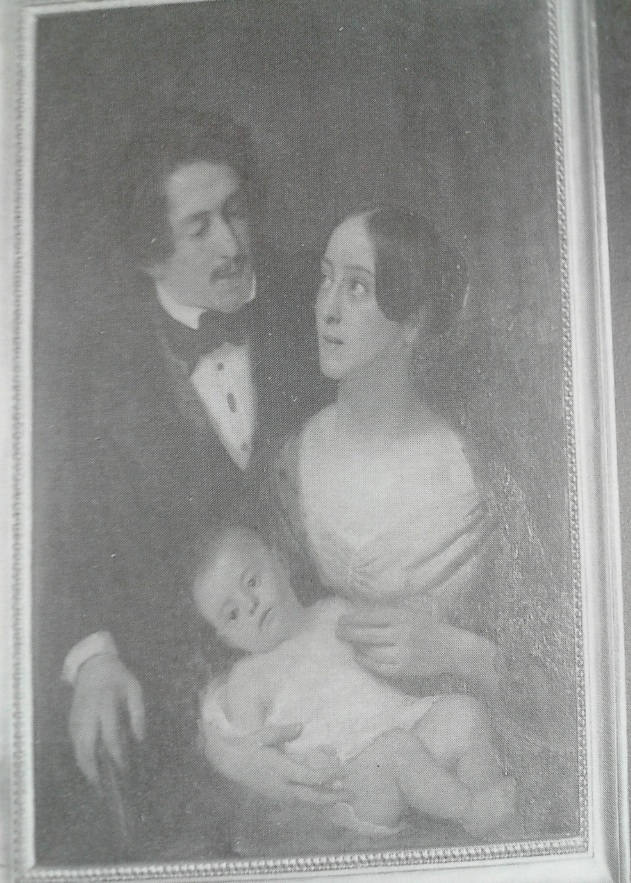

Giovanni Frizzoni (1805-1849)

Giovanni and Clementina Frizzoni (1815-1894)

with piccolo Teodoro (source of the two pictures:

Honegger 1997, p. 87 and p. 190)

Giovanni Frizzoni was, in several aspects, admired by the about eleven years younger Giovanni Morelli; but as fond as Morelli was of the other Giovanni, as fond he was of Federico Frizzoni too, who appears to have been, compared to his brother Giovanni, less extroverted, and more inclined, especially in later years, to the study of religious philosophy, while Morelli, nor a decided supporter of any church, nor inclined to a musing about philosophical or religious issues, shared literary and art historical interests with both friends.(17) Giovanni Frizzoni was married to Clementina (née Reichmann), the daughter of a German who had settled in Milan to run a hotel that was widely known among those who, coming from the North, travelled to Italy. Giovanni Morelli was also very fond of her, and this friendship, after the premature and tragic death of Giovanni Frizzoni in 1849, did also endure. Morelli later was to care especially for Gustavo Frizzoni, one of Giovanni and Clementina’s children, who, in the September of 1846, had just had his sixth birthday.(18)

What Engelhardt was now to experience with Morelli and the Frizzoni’s was the life of a cultured and endearing circle of friends, whose relaxed way of living was certainly to be referred to as being Italian, but also as being a combination of German, Swiss and Italian cultural influences. One was to play music in the evenings, if one was not playing billiard, or if not selections from works by Ariosto and Manzoni were being read aloud.

If Morelli excelled in reading aloud – it is not known to us, but only several years earlier he had had the chance to hear and see one of the most gifted reciter in Germany, namely Ludwig Tieck, whose one-man programmes of reading, reciting and rendering plays by Shakespeare and other playwrights to an audience (with all parts rendered and interpreted, masterfully, by his own voice), enjoyed an almost legendary reputation in German literary circles.(19) And Morelli had also been in touch with Gustavo Modena, one of the most gifted recitors of Italy, or Morelli, at least, had also had the chance to see and hear Modena recite, to play and to direct.(20)

With the works of Alessandro Manzoni Morelli was, of course, not only familiar, but as a most welcome guest also in the poet’s own house, he was someone who was more than just superficially acquainted with the writer and his works, situated, as far as the famous I promessi sposi are concerned, also in the Lake Como landscape (and also at Bergamo).

The Frizzoni brothers, on their part, had, in 1830, paid visit to no other than Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at Weimar.(21)

And if, at Villa Crella at San Giovanni, also selections from the Orlando Furioso by Ariosto were being read aloud, one may imagine that the house was not only filled with voices, with laughter, but also with images and sounds from chivalric adventures. Inspiring, not the least, actual excursions into the Lake Como landscapes, excursions that were to take place during the coming days and weeks.

*

THREE) ON LAKE COMO WITH MORELLI

›Thus we seated ourselves in a simple boat and, whilst having a vivid conversation and enjoying the glorious sun, had us pitch and toss over the waves.‹

························································································································································································································

»So setzten wir uns denn in einen einfachen Kahn und liessen uns über die Wellen hinschaukeln, indes wir lebhaftes Gespräch führten und der herrlichen Sonne uns freuten.«(22)

Detached from the civilisation’s goings-on, being away from society, being seated in a peaceful garden, we see Engelhardt with his young friend Morelli, only being seated in a simple boat, having these vivid conversations that Morelli certainly had joyfully anticipated, when knowing that his fatherly friend was to visit him again in his home country. And now they were having these conversations while rocking in a boat and on Lake Como.

It was in the very year of 1846 that an issue of the Baedeker had been published, dedicated to all German and to all Austrian territories, and as unfamiliar as it may sound today – this Baedeker issue, of course, did also include all the today Italian territories that were, to Morelli’s chagrin, being a part of Habsburgian Austria then.

Naturally this Baedeker did also dedicate several pages to the Como Lake region, and the traveller was, among other things, also informed on prices and on how to deal with rowers.(23)

That sort of preparations would certainly have appeared as being rather obsolete to Engelhardt, since his younger friend Morelli was, at the shores of Lake Como, practically at home. And having an intense conversation, on probably all things in life, we see our two travellers now, who were not only being on very familiar terms, but several years earlier had also come to a certain understanding as to how to, conveniently, express, and also publicly, many an opinion as to goings-on in the today world.

30-year-old Morelli was not in the position to publish his opinions as to cultural or political affairs – opinions, uttered passionately, and often being rather extreme – in German newspapers. But by courtesy of Engelhardt, in some sense, he nevertheless was. Since Engelhardt was a fully trustworthy name to the editors of the Allgemeine Zeitung, printed at Augsburg, and one, or even the one German newspaper of international reputation that was naturally also being read (for example by Swiss residents) in Italy.

And the point was that, if Engelhardt did publish articles or essays in the Allgemeine Zeitung, he was, not always, but sometimes, also slipping in the one or other text by his younger friend Morelli, segments from letters, namely, that Morelli had sent to Engelhardt. Resulting with Morelli, one may say, and certainly to Morelli’s and also to Engelhardt’s delight, resulting with Morelli being printed incognito.(24)

Passionate Morelli being censored or mildened, one might also assume or say, censored and mildened by Engelhardt. But be it as it may: indeed Morelli’s opinions, now and then, were to be read in the Allgemeine Zeitung, and the Engelhardt/Morelli cooperation presents us with a nice and also challenging problem of attribution. Because it is yet clear which articles, not very many articles, but some, were in fact Engelhardt/Morelli cooperations, but still it is not that easy to divide, one may say, the hands.

Although it might seem that the passionate voice of Morelli is clearly audible, if one does read the series of Italienische Briefe that was the actual main outcome of that having once come to an understanding, some years earlier, but still the historian or biographer is well advised to remain cautious as to the attribution of one or the other opinion to Engelhardt, to Morelli, or to both. However it is clear, and this without any doubt, that these articles are to be seen as an very adequate and also characteristic, since nicely hidden monument, that is as a monument to the Engelhardt-Morelli-friendship.

And what Morelli did when writing to Engelhardt (and by this in some sense writing for the Allgemeine Zeitung), was also documenting and portraying, explicitly and implicitly, his other important friendships. To the house, for example, of the already named poet Alessandro Manzoni. But also to the house of the Florentine nobleman and historian Gino Capponi, and the (informed) reader of the Allgemeine Zeitung was also to know about his friendship with, and about his particular admiration for the playwright Giovanni Battista Niccolini.

Beside that the reader of the Allgemeine Zeitung was to know also of how German travellers in Italy did misbehave and misunderstand the country and its people.(25)

But as an example of how Morelli did portrait and made known his friends to the German reader, we should like to take his portrait of Capponi from the Allgemeine Zeitung as an example:

Gino Capponi (1792-1876)

›He is a man of as noble a nature as of as illustrious a name, a man whose unusual erudition does all the more astonish, as it does not, as it often does occur, suppress, or at least has brought to a bay, the common sense and the rightful tact, but in him both have met in a most delightful accordance. His impressive appearance does vividly recall those men living at the day of Leo X, being the ornament to the court of Urbino; his stature, particularly his expressive face, would be worth to be eternalized by a Titian. He does belong to the few remainings of Italian thoroughbred. To him God has given, to a high degree, the astuteness to recognize and to accept everyone in his particular line of mind and temper, which is so rare, so most rare in our days, in which an eye for individuality hardly is to be found at all. This gift of a psychological astuteness of mind marks this Italian as an authentic artistic nature. To find this being true in its most complete sense, one has to listen to him speaking on Italian history, has to hear how he does outline, in fiery narration and with his low and Herculean voice, the stature and personality of this or that Pope, with indeed Shakespearian brushstrokes, [one has to see] how his face then turns to be more and more meaningful, how his eloquence turns to be more ravishing, and how the noble man in the ardor of passion does forget his misfortune. Because ever since several years he is blind.‹

·················································································································································································

»Er ist ein Mann von ebenso edler Natur als glänzendem Namen, und dessen ungewöhnliche Gelehrsamkeit um so mehr in Erstaunen setzt, als sie nicht, wie oft zu geschehen pflegt, den gesunden Menschensinn und den richtigen Takt verdrängt oder doch in die Enge getrieben hat, sondern beide sich in schönster Eintracht bei ihm zusammengefunden haben. Seine imponierende Erscheinung erinnert lebhaft an jene zu Leo X. Zeit lebenden Männer, die den Hof von Urbino schmückten; seine Gestalt, zumal sein ausdrucksvolles Gesicht wären wert durch einen Tizian verewigt zu werden. Er gehört zu den wenigen Überresten italienischen Vollbluts. Ihm hat Gott in hohem Grade den Scharfsinn gegeben, jeden in seiner besondern Geistes- und Gemütsrichtung zu erkennen und gelten zu lassen, was so selten, so höchst selten in unsern Tagen ist, wo ein Auge für Individualitäten fast nicht mehr gefunden wird. Diese Gabe des psychologischen Scharfsinns bezeichnet diesen grossen Italiener als eine echte Künstlernatur. Um dies im vollständigsten Sinn wahr zu finden, muss man ihn über italienische Geschichte sprechen hören, muss hören wie er im Feuer der Erzählung mit seiner tiefen und herkulischen Stimme die Gestalt und Persönlichkeit dieses oder jenes Papstes mit wahrhaft Shakespear’schen Pinselstrichen zeichnet, wie da sein Gesicht immer bedeutender, seine Beredsamkeit hinreissender wird, und wie der edle Mann in der Glut der Begeisterung seines Unglückes vergisst. Denn er ist seit mehreren Jahren blind.«(26)

If we see now Engelhardt and Morelli rocking in a boat on Lake Como, we might imagine that they were talking about further such articles and about further journalistic cooperations, but we should not assume that Engelhardt, although being a fatherly friend to Morelli, was the one only fatherly friend to Morelli. In truth, and this is very characteristic for Morelli who had lost his own father when being only four years old, he had at least three such friends. Next to Engelhardt, or next to the one German fatherly friend, there was Capponi, whom Morelli did love as much as Engelhardt, and explicitly loved like a son loved his father.(27)

Capponi had experienced, as we have read, the tragic fate of having almost completely lost his eyesight, and apparently, Morelli’s love to him went as far, in times that one was experimenting with hydrogene cyanide as a medication, as to thinking if this substance could not be of help to Capponi, and namely as to thinking about experimenting with hydrogene cyanide in apparently wanting to apply this substance to an already blind horse.(28)

If Morelli used to compare Capponi – who disposed of this particularly impressive voice, a bass voice, that was also referred to as a ›voice of Menelaos‹ –(29) to Renaissance men and to a circle of courtiers and artists, he did in some sense, refer to himself as belonging to the second generation of such a circle. And if Engelhardt also did advise Morelli as to own journalistic and particularly literary activities, so did Capponi, and the two men, both being men of the world and in their own way experts of human nature, do represent to us the two sides of Morelli’s cultural identity, the German side, the side of German Bildung, and the Italian side, the Renaissance side, if one likes so, since young men like Morelli did find their cultural references partly in their contemporary culture, but mainly, the more admired cultural references, they did find in the Italian past. And Capponi, who as a young man had witnessed historical events such as the execution, at Mannheim in 1820, of student Karl Ludwig Sand, the assasin of writer August von Kotzebue, and who had stood in front of Napoleon Bonaparte (wearing ill-fitting emperor’s vestments, as one did specifically recall)(30) did certainly recommend classic literary models to Morelli, beside that contemporary politics and literary affairs were being discussed within the Florentine Capponi circle.

To the two Frizzoni brothers Morelli had described Capponi also in the following way:

(Picture: scalaarchives.com)

›The blissfulness that I sense, to be allowed to associate with a man like Capponi, I can hardly express in two words. Who does know him better, in him does find the open loving harmlessness of a youth, the serious maturity of the complete man, the full extent of knowledge, the cordiality of serious, serene, simple and substantial conversation; no ostentation, no pettiness, nothing dry-as-dust, sophisticated, no secret-mongering nor touches of tenseness, as this is more often the case with scholars and literary men, who, as one does say, are to be considered as ›shining‹. And this all permeated by that deep and yet serene melancholy, which always does accompany the great and unfortunate man, spiced by own features of Socratic irony, by which from time to time he does give vent to his unwillingness and his pain. […]‹

··································································································································································································

»Die Glückseligkeit, welche ich empfinde, mit einem Manne wie Capponi Umgang zu haben, kann ich kaum in zwei Worten ausdrücken. Wer ihn genauer kennt, findet in ihm die offene liebevolle Harmlosigkeit eines Jünglings, die ernste Reife des vollendeten Mannes, den vollen Umfang des Wissens, die Herzlichkeit einer ernsthaften, heitern, einfachen und gehaltvollen Unterhaltung; keine Grosstuerei, keine Kleinlichkeit, nichts Trockenes, Sophistisches, keine Geheimniskrämerei noch Anflüge von Gereiztheit, wie dies bei Gelehrten und Literaten, die, wie man sagt, auf dem Leuchter stehen, öfters der Fall ist. Und dies alles durchdrungen von jener tiefen und doch heitern Melancholie, welche immer den grossen und unglücklichen Mann begleitet, gewürzt durch eigene Züge sokratischer Ironie, mit welchen er von Zeit zu Zeit seinem Unwillen und seinem Schmerz Luft gibt. […]«(31)

All in all one may say that Morelli, if he was mentored by Engelhardt and by Capponi, was mentored by men, that were representing a European literary culture, but each representing also a more specific culture, and a more specific, and of course also individual world view. And it is Morelli’s biography, it is Morelli, as an individual, who was educated by such men, who is enabling us today to make this journey, this rather unusual journey, a transnational journey through 19th century literary cultures, and through 19th century politics. And this journey, due to such mimicry as indeed was the Engelhardt/Morelli mimickry of common authorship, is not lacking elements of the picaresque novel and particularly not lacking elements of comedy, although the picaresque elements of Morelli’s biography do also specifically reflect the difficulties of having or wanting to settle in various cultures, and to lead a transnational or bi-national existence, which was, to Morelli’s chagrin, often also an existence inbetween the cultures, and one may add, also, and paradoxically, due to Morelli’s talent for friendship, an existence of being torn between various friendships.

Bonaventura Genelli (1798-1868)

A view on Bellagio from the Tremezzo side

(source: Binder 2007, p. 306)

Beside the two literary advisors and fatherly friends to Morelli, both by the way being historians, we have, of course, to name a third friend. Also a mentor, but wanting to be more a friend than a father, and this was Munich-based artist Bonaventura Genelli, who lived under precarious circumstances with his family at Munich and had enjoyed the friendship with Morelli for about a year, in 1837, at Munich, until the latter had left for Erlangen (where the bonds of the friendship with Engelhardt had originated).(32)

Genelli, as a character has to be seen, to some degree, as a counterpart to Capponi and Engelhardt, as the two men of the world, since Genelli, a very authentic and noble, sensitive and warm-hearted character, was known in Munich society for having no tact at all, in society, (and without any doubt, Morelli did love Genelli particularly also for this being very authentic, partly due to a lack of tactfulness, and for this being honest).(33)

But warm-hearted Genelli, who was not much dedicated to the writing of letters, to not a little degree now did also suffer that his dear friend Morell was absent, had left Germany all too soon, and all too decidedly. To live in Italy, where it was not the least the bonds of friendship with Capponi, and the circle and the house of Capponi, that made Morelli feel that his place was there. In Italy. Among cultured friends, and, as Morelli was also decided, not among silk merchants (or at least not too much).

A certain rivalry of friendship might also have existed, although, or just because Morelli did name three men to Genelli as the three men that he did love the most, namely Genelli, namely Engelhardt, and namely Capponi.(34) And Morelli did speak, if he was referring to these three man as being crucial to him, certainly of those that, as a group as one may say, replaced his own father to him. Since, if one was to speak of his whole circle of friends, including those, like the Frizzoni brothers, who were more like (in this case: elder) brothers to him, one would have also to speak of Niccolò Antinori, who did also belong to the Capponi circle. And we will certainly come back to all of them.

Here we look at the Lake Como promontory with Bellagio and the Villa Serbelloni on the left, with Taronico in about the center, and with San Giovanni and its church on the right

(picture: RaminusFalcon; with a segment of the glorious original phograph being used here)

In the meantime Engelhardt and Morelli, being rowed or rowing themselves directly from San Giovanni towards Tremezzo, might have reached the other shore, but possibly, as one might well imagine, they were still vividly speaking of the one or other literary project. Since Engelhardt, like, again, Capponi, was allowed to hear (or as here: to read) Morelli’s own literary products, namely: plays.

Plays of which Morellian studies have, as yet, hardly taken notice of, but being the probably most ambitious intellectual occupation during the first half of his life, one cannot speak of Morelli without considering the poet and playwright-to-be that Morelli saw in himself (as, for example, also Genelli saw in him) or at least the playwright that he wanted to be and projected to be for a long time.(35)

Morelli, in a word, and this was one of the central ironies of his whole life, did, during the first half of his life, consider art connoisseurship not as something that he was to take up as a profession. On the contrary: in 1846, and until about 1858, Morelli did consider art connoisseurship as the one field of human pretention that he was to draw from if writing a comedy. Like for example and particularly that comedy that he had written, in 1839 when being in Paris, a comedy entitled Kunstkenner (›Connoisseurs of Art‹).

Although ›real‹ art connoisseurship did exist for him also at that time, it was about to ridicule and to satirize the pretentious side of connoissseurship, and to cherish that subject, as his friend Genelli had advised him to do. And Morelli had indeed sent that comedy with the significant title of Kunstkenner to his friend at Munich to read (and Genelli, on his part, had also allowed the painter Carl Adolph Mende to read that comedy as well). And both had read it to their delight.(36)

But in 1846 other subjects were on Morelli’s mind. He was into reading Calderón, the Spanish poet and playwright, and namely into The Surgeon of his Honor of 1637 (Engelhardt was about to hear about the plot of that play when both, Engelhardt and Morelli, were taking a stroll in the lovely gardens of Villa Melzi, during that stay at Lake Como). And Engelhardt was also about to read a play by Morelli himself named Soverchia premura nuoce, a play that, according to Morelli’s own later testimony, Engelhardt found, if not being void of weaknesses, yet superior, if being compared to contemporary comedies by German playwrights like Karl Gutzkow or Heinrich Laube.(37)

Morelli and Engelhardt might have discussed also political affairs during their stay at and on Lake Como, and Morelli certainly, at that time, was still enthusiastic about a new pope, a seemingly liberal pope, Pius IX, who had just been elected and bore the hope of the Italian patriots, and of the younger generation very in particular. And with Engelhardt Morelli guided a traveller through the Lombardic Pre-March Era who was not interested to travel like a common tourist. Engelhardt, on the contrary, was a traveller, and his reports show this to great detail, who was taking a deep interest in the country, its people, its political and cultural affairs (and this extended even to Engelhardt, the professor of theology at Erlangen, exploring the Lombardic techniques of bird catching, with the professor in fact once kneeling down in hiding, together with a Lombardic bird catcher, having prepared his nets, with Engelhardt, one might say, being a participating observer).(38)

Momentarily Morelli and his fatherly friend Engelhardt immersed themselves also, when visiting a splendid villa at Lake Como, into a certain daydreaming, into a fancying of being the owner of such a lodging.(39) Morelli was actually to reside in Villa Balbianello a couple of years later, in 1850/51, and together with his mother, his aunt and with his friend Niccolò Antinori very in particular, whilst the actual owner, Count Arconati, resided, at that time, again far from home, as he was also in 1846, for being a liberal and therefore being a political refugee, living in exile.(40)

But in 1846, with Engelhardt, it was about visiting such lodgings, their actual owners for the most part, being absent, and also about getting to know the more hidden society of those who actually did take care of the buildings and gardens in the meantime.

And it was also on such a trip that Engelhardt was able to witness how 30-year-old Morelli, together with the Frizzoni brothers, was looking at art, and this in one of the most famous villas at Lake Como (famous particularly for its gardens, but also for its art collection). It was to be on another day, when all of them – Morelli, Engelhardt, but also the Frizzoni brothers, payed a visit to Villa Carlotta (then referred to as Villa Sommariva) as a group. And the voices that Engelhardt, the participating observer, could hear on that occasion almost linger on into our day. Since some of the sounds, some of the tunes may perhaps sound familiar to the reader of Morelli, familiar already with the voice of later Morelli, alias Lermolieff.

*

Villa Carlotta (picture: GhePeU)

FOUR) A SCENE OF CONNOISSEURSHIP OR: WITH MORELLI, ENGELHARDT AND THE FRIZZONI BROTHERS IN VILLA SOMMARIVA (VILLA CARLOTTA)

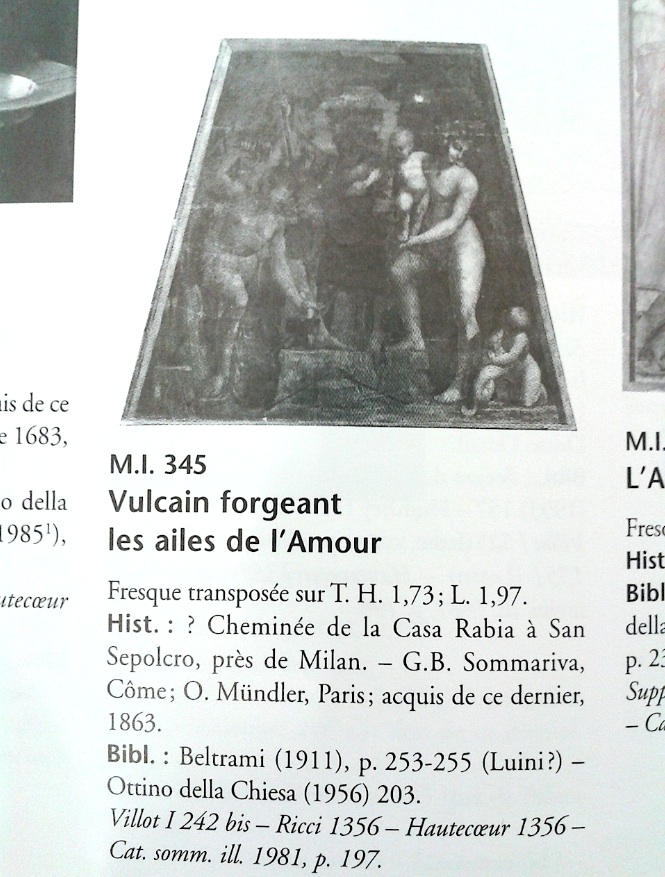

It is significant that Engelhardt did’t even try to distinguish the voices, the ultracritical voices that he heard: This was a group of tight friends, or, as Engelhardt had it also, of ›ultracritical critics‹. But we owe to the German professor this precious account, as to 30-year-old Morelli, and as to the two Frizzoni brothers, Giovanni and Federico, all of them together, and also probably with their wives and with Engelhardt, looking at art at Villa Carlotta (then Villa Sommariva). And it might even be seen as a proof of Engelhardt being very observant, if we seem to hear the voice of Giovanni Morelli, as we know it from later writings, mingling here probably also with the voices of Giovanni and Federico Frizzoni:

(Picture: alinariarchives.it)

›We step into the house and at first into the hall which is decorated by Thorwaldsen’s Wars of Alexander the Great and wherein is to be found the magnificent statue of Palmedes by Canova; we look at the landscapes by Hackert and with interest we do inspect a picture that is attributed to a master which we do know well enough elsewhere and by his most laudable side, not to be seen here – Luini; we see nice floral still lifes and pictures of the Dutch school. – The men do enjoy to find something to criticize everywhere, and thus the great work by the Danish master had to put up with them missing, as to the composition, an idea, infusing the whole in all its parts, or, to put it more clearly, with them finding as to single figures imitations of classic works, which, being as such worked out exquisitly, fail to have the whole make an effect of a perfect unity on the beholder. Solely the more genre-like elements of the work, the herds, the spoils, the captives etc. found the full approval of the ultracritical critics, as well as the beautiful Palamedes, in regard to which they only were’t able to clarify which Palamedes the statue was meant to render. Whilst looking at landscapes by Hackert they showed repeatedly surprised, how Goethe could have attached such importance to these landscapes; the Luinesque picture they deemed to be not authentic or being much damaged. – Without any doubt, in regard of the work by Thorwaldsen, they felt like wanting to spice their enjoyment of the work by haughty criticism, and the haughtiness of the happy ones articulated in them, whilst finding themselves surrounded by the abundance of natural beauty, and whilst being confronted with a masterwork which had already many times gladdened them in their soul, as being engraved by Amsler, and commented upon, unforgettably, by Schorn.‹

························································································································································································································

»Wir treten in das Haus und zunächst in den Saal, den Thorwaldsens Alexanderzug schmückt, und in dem Canova’s herrliche Statue des Palamedes steht, wir sehen uns die Hackert’schen Landschaften an und beschauen mit Interesse ein Bild, das einem Meister zugeschrieben wird, den wir von sonsther zur Genüge und von der rühmlichsten Seite kennen, die hier nicht hervortritt – Luini; wir sehen schöne Blumenstücke und Bilder aus der holländischen Schule. – Die Männer lieben, überall etwas zu kritisieren, und so musste es sich das grosse Werk des Dänen gefallen lassen, dass sie an der Komposition eine das Ganze in allen seinen Teilen durchdringende Idee vermissten, oder um es deutlicher zu sagen, dass sie in den einzelnen Figuren Nachbildungen antiker Werke fanden, die, an sich vortrefflich gearbeitet, doch das Ganze nicht als vollkommene Einheit auf den Beschauer wirken lassen. Nur das Genreartige des Werks, die Herden, die Beute, die Gefangenen u[sw]. erlangten die vollkommene Billigung der überanspruchsvollen Kritiker, ebenso der schöne Palamedes, bei dem sie nur nichts aufs Klare kommen konnten, welchen Palamedes die Statue eigentlich vorstellen sollte. Indem sie sich die Hackert’schen Landschaften besahen, wunderten sie sich wiederholt, wie Goethe ein so grosses Gewicht auf diese Landschaften habe legen können; das Luinische Bild erklärten sie für unecht oder für sehr verdorben. – Ohne Zweifel sprach in Bezug auf Thorwaldsens Werk aus ihnen der Übermut der Glücklichen, die [im Original: der] sich in der Überfülle der umgebenden Naturschönheit und einem Meisterwerke gegenüber, das sie in Amslers Stiche mit des unvergesslichen Schorn Erklärungen so oft in der Seele erfreut hatte, durch kecke Kritik den Genuss noch würzen wollten [wollte].«(41)

If we seem to hear, with this report, the voice of art connoisseur-to-be Giovanni Morelli, who was going to throw the scenery of European art connoisseurship into a dither several decades later, we have also the chance to obtain a more realistic picture of his actual beginnings as a connoisseur. Because this picture, given to us by German professor Veit Engelhardt, shows, among other things, how Giovanni Morelli did learn. Namely from being in conversation with his somewhat elder friends, and at times being in somewhat enraged conversation with particularly Giovanni Frizzoni. Who, by the way, was not the one of the Frizzoni brothers who was really dedicated to painting, and particularly to the collecting of paintings.(42) Federico Frizzoni was, but it had been Giovanni Frizzoni, only a couple of months earlier and probably at Bergamo, against whom 30-year-old Morelli had spoken out rather harshly, in his typical passionately emotional way. And why? Because they had not agreed of how to to look at a picture (a drawing by Genelli), that Giovanni Frizzoni had, seemingly more inclined to look at a picture like, well, like a Morellian. Whilst it had been Giovanni Morelli feeling as if he had been provoked by such a looking at art, himself, at the time, wanting merely to savour the looking at a picture by his dear friend Genelli.

Since Giovanni Morelli, feeling that he had spoken out rather harshly, against his otherwise splendid and much loved friend, had pictured to Genelli, by letter, the whole scene, we have a chance to witness this telling scene also: a scene that seems to show, if we think of how Giovanni Morelli, by art historical tradition, is conventionally depicted, the inverted picture. With Morelli making, eloquently, the case for the enjoyment of art, while it was up to Giovanni Frizzoni, the other Giovanni, to seemingly make a case for the looking at the small defects in a drawing, in other words, to make a case for the looking at what later was to be called, by art historical tradition, the Morellian detail:

One of the Luini pictures that belonged to the Sommariva collection for some time

(and maybe the picture that the connoisseurs of 1846 were looking at) was acquired by

Giovanni Morelli’s later mentor Otto Mündler who did sell it to the Louvre in 1863

(source: Habert et al. 2007, p. 84).

›And against Giovanni, who is, in other respects, agreeing to my accolade, I have spoken out somewhat harshly because of him dwelling on a hand, being too small, and on a thigh being too long. Such critical remarks are fit to indeed enrage me every time, since, partly due to my own eye, in a moment of enthusiastic enjoyment, not being able or not wanting to perceive the small defects, partly also due to such a remark, be it perfectly based on reasons, unexpectedly and adversarially dropping in on us. Later it may be made, and if we find it to be important, we shall be ready to admit it (being substantial), convinced of no man-made thing (ever) being perfect. This is how I feel almost every time, if I am looking at works of art with the otherwise splendid Frizzoni brothers or with other acquaintances of mine – and this factor has, in my life, diminished many a time my enjoyment of art and filled it with bitterness, resulting with my every time being decided, never to step into a gallery (of art) with so-called connoisseurs (of art).‹

····················································································································

»Und ich habe mich ein wenig hart gegen den sonst auch in mein Lob einstimmenden Giovanni ausgelassen, weil dieser sich über eine zu kleine Hand und über einen zu langen Schenkel aufhielt. Solche kritische Bemerkungen können mich jedesmal wahrhaft in Zorn bringen, weil teils mein Auge in dem Momente des begeisterten Genusses die kleinen Fehler nicht wahrnehmen kann oder nicht mag, teils aber auch, weil eine solche Bemerkung, wenn sie auch noch so gegründet ist, doch immer als unerwartet und als feindlich uns überfällt. Später mag sie gemacht werden, und wenn wir sie wichtig finden, werden wir sie gerne zugeben, überzeugt, dass kein menschliches Werk vollkommen ist. So geht es mir aber fast jedesmal, wenn ich mit den sonst trefflichen Brüdern Frizzoni u mit andern von meinen Bekannten Kunstwerke betrachte – und dieser Umstand hat mir in meinem Leben so manchen Kunstgenuss geschmälert und verbittert, so dass ich mir jedesmal vorgenommen hatte, niemals mit sog. Kennern in Galerien zu treten.«(43)

From this very passage of a letter to Bonaventura Genelli we may learn many a thing (beside of taking Giovanni Morelli declaring to be ›decided‹ with a grain of salt): for instance that 30-year-old Morelli did not feel to belong to that species of so-called connoisseurs at art, when being thirty years old. In implying that Giovanni Frizzoni was one (maybe Giovanni would’t have agreed to that), Morelli indirectly was referring also to another well-known connoisseur, and namely to Carl Friedrich von Rumohr, who had been a dear friend to the Frizzoni brothers (and Morelli had also met Rumohr, if only briefly, at Berlin in 1838, and it certainly had been due to introductions given to him by his friends, introductions to such personalities as Rumohr that he actually had had a chance to meet them).(44)

The passage does also show beautifully the two sides of connoisseurship, the immersing into the qualities of a work of art that an amateur, a lover of art and not least connoisseur actually seeks to savour, and on the other hand the more detached gaze at qualities, understood now as marks, as well, as at – possibly – small defects (also understood as being, in a neutral and simply essential sense ›qualities‹), that might come into question if it is more about a classifying, dating and attributing of a picture. And we do not say too much if saying that this very passage from a letter of Giovanni Morelli to Bonaventura Genelli does foreshadow many an (enraged) conversation about such matters, not only in the biography of Giovanni Morelli (or other connoisseurs like Bernard Berenson), but in the whole history of connoisseurship to come.

If we now think again of the first scene at Villa Carlotta, depicted by Engelhardt, we might also think of the private tutor of the two Frizzoni brothers, a Saxonian named Gustav Gündel, who also knew Morelli, and who actually had been trying to make his pupils to take something to heart: that there was a fatal ›cloverleaf‹ on the ›field of social relations‹ – namely »cavilling, heat, self-opinionatedness«.(45) And one might say that Gündel knew his protégés fairly well.

The landscapes of Lake Como are not necessarily to be regarded as being a lieu de mémoire to the history of connoisseurship. But we might still, particularly if thinking the two depicted scenes together, claim that we have witness a theatre of memory, as to the history of connoisseurship, here.

*

FIVE) A DISTANT VISION AT VILLA MASSIMO D’AZEGLIO

During the 1840s Giovanni Morelli was to learn many a thing as to art affairs in the city of Munich, which had been the city of his studenthood. His Munich-based friend Genelli, if not gossiping, but yes, at times indeed gossiping, did inform him as to the goings-on of artists, as to diatribes, successes, hopes and wishes, and as to the Munich art world at large.

And once Genelli was to inform Morelli that he had been rather surprised by what he had heard from another friend, of Vienna-born painter Moritz von Schwind, who knew Morelli as well (or at least of him), and who had, apparently and to Genelli’s astonishment, turned to be rather modest, not as to his artistic ambitions perhaps, but as to social ambitions, and as to the way of life, Moritz von Schwind did actually aspire and hope for:

›Because upon my revealing of a ›wish for a cat‹, that I mentioned towards Schwind, namely to have a couple of millions, so as to erect a villa with this, a villa which I could, in all freedom, paint in – he answered: ›Ever since a long time I am not thinking of gardens and villas any longer, but of, in all seriousness and in case I have yet, for some years more, managed to fight a running battle, a small house at a place with a cloister, with a library, organ, hunting parties and a nice scenery. Meadows for a couple of cows, garden for cabbage and potato, and if it goes fairly well, an old grey horse, to rightly shake my liver. I would be able then to do nothing except miniatures like the quaint saint and such stuff. My luxury would be drawings done by you.‹‹

························································································································································································································

»Auf einen Katzenwunsch, den ich nämlich gegen Schwind äusserte, nämlich ein paar Millionen zu besitzen, um damit eine große Villa zu erbauen, die ich denn in aller Ungebundenheit ausmalen könnte – antwortete er ›An Gärten und Villen denke ich lange nicht mehr, wohl aber allen Ernstes, wenn ich mich noch einige Jahre herumgeschlagen habe, an ein kleines Haus in einem Ort, wo ein Kloster ist, mit Bibliothek, Orgel, Jagden und schöner Gegend. Wiesen für ein paar Kühe, Garten für Kraut und Erdäpfel, und wenns recht gut geht, einen alten Schimmel, der mir die Leber zu recht schüttelt. Ich wäre im Stande, dann nichts zu machen als Miniatüren wie der wunderliche Heilige und solches Zeug. Mein Luxus wären Zeichnungen von Ihnen.‹«(46)

Not a villa, in a word, but the Biedermeier vision of being set up conveniently, not having much to desire, except peace and quiet, and this, from the perspective of Genelli, seemed perhaps to be a little bit all too modest for an artist not lacking also a political conscience.

Morelli, by the way, was certainly considered to be rich by Genelli, and Morelli was in fact eager to help Genelli out as best as he could. Fancying to be the owner of his own villa Morelli also was occasionally (as we have seen), but, according to his nature, also rather being pleased with fancying.

And if on the other hand Morelli had been, earlier in the year of 1846, fancying Genelli decorating a villa at Lake Como with frescos (and maybe from the life of Hercules), it is only all too believable that Morelli indeed wished this dream to become true.(47)

Even at that time, at Lake Como and as a tourist, one was observing how the high society had made their dreams of splendid lodgings to become true, but as said, many villas, in September of 1846 and to Engelhardt’s musing, stood empty, because of their actual owners being away and somewhere else.

This did not prevent Morelli and Engelhardt to pay visit to some of these villas, on the contrary: many an insight into these villas was possible (and not the least a sneaking into the impressively large kitchen of Villa Giulia).(48)

And many an insight, certainly also due to Morelli easily socializing with people from all social classes, into the organization of society at Lake Como, beyond the splendid surfaces of more or less exquisite architecture, and beyond the natural beauty of the scenery.

One did meet in the first place, in this September of 1846, the class of the custodians of high society villas, including their families (if they had such). The beautiful daughter of a castellan thus finds mentioning, opening the iron gate to our two travellers, coming in by boat to pay a visit.

And another castellan, pretending that he would bore himself to death, being only the custodian of a Lake Como villa, if he hadn’t had the chance to have a piano, and also the time and leisure to play it.(49)

Where one was supposed to study the luxury of the possessing classes, in a word, one was also to study the society of normal people, enjoying, as best as they could, their Biedermeier vision (if the word may be allowed) of peace and quiet. Not peace and quiet in the niche perhaps, but here, as one might say, peace and quiet in the vestibule of a Lake Como villa or in a cosy garden.

Massimo d’Azeglio (1798-1866)

But if actual owners of splendid lodgings were away, when our travellers were heading to visit them, this was not necessarily due to an enjoying of peace and quiet only at another place. At least in one particular case the absence of the actual owner of a villa was significant as to exactly the opposite. Significant as to this inhabitants other, namely political ambitions (although also the artistic ambitions were clearly visible).

And this particular owner of a Lake Como villa had not fled to exile, but had turned from being a painter and a writer, to be a political activist, in a word: a Risorgimento politician: Massimo d’Azeglio – Morelli knew him probably, if not very well, due to himself being a member of the Capponi circle – apparently was out. But the Villa d’Azeglio, as many other villas, stood open to our two travellers.(50)

Massimo d’Azeglio, The Battle of Legnano

Engelhardt probably was not aware who Massimo d’Azeglio had turned to be in recent years, and if Morelli was aware – it is difficult to say, judging merely upon Engelhardt’s report.

It was on another day, filled with another excursion into the Lake Como scenery. And this excursion led to the Villa d’Azeglio above Menaggio (above the today Villa Vigoni with the today »Deutsch-italienische Zentrum für europäische Exzellenz«).

Engelhardt did take notice the utensils of painting (d’Azeglio had painted landscapes, but also historical scenes, redolent of the tensions and political hopes of the Lombardic Pre-March-Era), and Engelhardt had the chance also to cross the study of the novelist Massimo d’Azeglio, to step out to the altana, and to glance over, again, and from another point of view, at Villa Serbelloni on the Bellagio promontory.

On their way to Villa d’Azeglio our two travellers had also encountered a German landscape painter, accompanied by his wife being eager to prepare the colors for her husband.(51) And only a few steps away from this Biedermeier idyll our two travellers were allowed to enter the home of Massimo d’Azeglio, the painter, novelist and Risorgimento activist that d’Azeglio was about to become.

In a word: Only a few steps away from a travelling Biedermeier idyll our two travellers, Morelli and Engelhardt, our two politically most conscient travellers, did enter a scenery of the Lombardic Pre-March Era.

Only with the main protagonist of that scenery being just away, a scenery despite or just because of Massimo d’Azeglio being away, a most significant scenery. Because the being away, the staying out of Massimo d’Azelio, meant, that the former painter and novelist, in the year of 1846 which had seen the election of a pope that was already bearing the hopes of all Italian patriots, was being active.

One was’t yet to foresee which exact role Massimo d’Azeglio, by history, was given, nor was one to foresee that Pope Pius IX was going to bitterly disappoint the hopes of the Italian patriots (including hopeful 30-year-old Giovanni Morelli), in the following. But the year of 1847 was to see the manifesto of the moderate Italian liberals, penned down by no other than Massimo d’Azeglio.

One may assume that Engelhardt, who, by the way, in the meantime had also revised his initial judgment as to the Lake Como scenery,(52) knew much more of the political fermenting also clearly visible at Lake Como at that time, in September of 1846, much more than he was keen to reveal in his reports. The year of 1847 was to bring corn riots at Varenna that the observant parish priest of Varenna was yet capable to appease,(53) but the Lombardic Pre-March era had clearly entered its final stage of fermenting, although Engelhardt certainly would never have guessed which exact role his young travel companion, his guide into the Lombardic Pre-March-Era, was going to take. Nor, certainly, would have guessed 30-year-old Giovanni Morelli himself, who, at that time, might have been prepared to see the outbreak of a series of European revolutions, but was, as we will see, also surprised, when the actual revolutions, followed also by the First Italian War of Independence, actually were to come.

***