M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

SPECIAL EDITION

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2  |

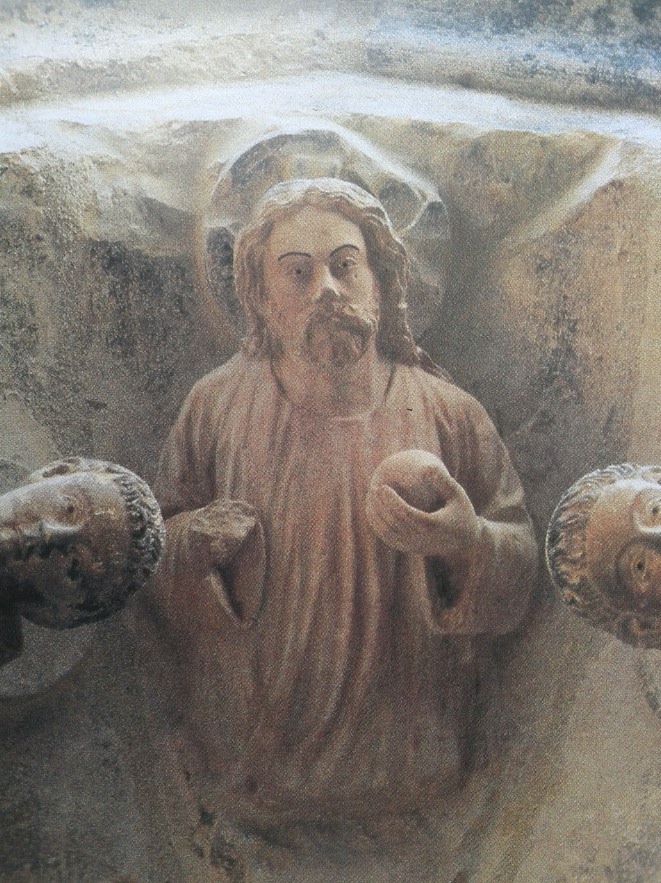

(15.-16.7.2023) In our first contribution on medieval Salvator Mundi iconography we had seen that 1) Salvator Mundi iconography did exist at around 1019 and earlier (and in the wake of Charlemagne, who had adapted the orb as one insignia of a ruler, so that also Christ, as the ruler of all earthly rulers, could be invested – in art – with that insignia; 2) that Salvator Mundi iconography was attractive for any ruler, king or emperor, wanting to evoke the Divine Right of Kings, i.e. the belief that the earthly ruler was actually exerting his rule by mandate of Christ, the ruler of all rulers; 3) that Salvator Mundi iconography did exist also as part of other iconographic patterns, such as the Madonna Enthroned with the Christ Child; and 4) that Salvator Mundi iconography did exist and was transmitted to the era of the Renaissance in various media, from sculpture to the wood cut.

It is now time to work, in a second step, more towards systematization, and towards an actual overview on medieval Salvator Mundi iconography.

(Picture: DS; after: Reims

(Connaissance des Arts series, p. 45))

(Picture: Palauenc05)

1) The Universe of Reims or Salvator Mundi Iconography and the French Monarchy

On the left we see our first reference point, which is Charlemagne. Who did introduce the Dei gratia formula as a ruler, and who did choose to be represented like an ancient ruler: holding as one of his insignia as a ruler the orb in his one hand. We see the well-known equestrian statuette.

From Charlemagne we might turn now to inspect, in chronological order, all medieval imperial iconography in the wake of Charlemagne, in order to find corresponding representations of Christ as the ruler of all rulers. The one example we had already seen in our first contribution as to the topic of medieval Salvator Mundi iconography had been the Basel Antependium (around 1019), and indeed we would find, for example in a Cross reliquary from the Staufian era, Salvator Mundi iconography (see here).

But instead of organizing this gallery of medieval Salvator Mundi iconography chronologically, I am chosing to show more examples of French Salvator Mundi iconography first, examples which are meant to illustrate the bond between a spiritual order and a political order, a bond which was indicated by combinations of Salvator Mundi iconography with the iconography of the French monarchy. In the universe of Reims Cathedral, for example, we find, on top of the so-called Portails des Saints, a probably little known representation of Christ (on the right), which probably is, respectively has been a representation of Christ as the Salvator Mundi, although the hand, which was probably a blessing hand, is lacking.

And in the so-called Psalter of Saint Louis, on folio 85v (see below), we find a beautiful example of the aforementioned bond (there are more examples in that Psalter, which I recommend to inspect, but the Salvator Mundi on folio 85v is my choice).

And there is also more to say on the Notre-Dame-du-Pilier at Chartres, which might be a sculpture from the 16th century, but belongs to a tradition of representations of the Mother of God shown enthroned, holding the Christ Child which is represented as a Salvator Mundi, and there is a whole group of such wooden sculptures, also from France, and from the very late 12th or the early 13th century.

(Picture: Detail of folio 85v from the Psalter of Saint Louis; source: gallica.bnf.fr)

(Picture: Doppelklecks)

2) Sedes Sapientiae: The Christ Child as a Salvator Mundi

On the left again a reference point, which is a representation of the Madonna Enthroned from the Hagia Sophia, without the Christ Child being represented as a Salvator Mundi, but this is an iconographical pattern from Byzantine art, which easily could be adapted, so that, in the 13th century we find actually a whole group of sculptures, all belonging to that Seat of Wisdom or Sedes Sapientiae tradition, and examples are scattered in museums around the world. And another variant is the Madonna being represented as standing, but also holding the Christ Child which is represented as a Salvator Mundi (with the orb sometimes turning to be apple, or an apple turning to be orb). We find one example in the Cathedral of Cologne, which is the so-called Mailänder Madonna. And for comparison one might turn for example to the so-called Füssenicher Madonna.

3) Medieval Salvator Mundi Iconography and Medieval Global Salvator Mundi History

The combination of Salvator Mundi iconography with an actual world map is again a hint that Salvator Mundi iconography has not only a apiritual, but also a political side: rule means, here, ruling the world, the cosmos, the universe (as it was thought in medieval times). Above we see the so-called Psalter World Map, respectively the Salvator Mundi, on some level, presiding over that map. And the political side of Salvator Mundi iconography shows here in a book that actually was dedicated to Old Testament poetry: the Psalms. But since King David was and is thought to be the author of Psalms, the bond between poetry, the spiritual and the political is present anyway: if a ruler was appealing to the Lord or to God the Father, in terms of praying or singing, the ruler was appealing to the supervisors of earthly rule and the author of the representation of Christ as a Salvator Mundi, presiding over a world map, was highlighting a unity of the spiritual and the political order, a unity which could be adapted, following the example of King David, by any medieval ruler, emperor or king (as seen above).

(Picture: Peter Portner)

4) Towards the Renaissance: the 15th Century

Since we know that Leonardo da Vinci had to provide, when working on the Virgin of the Rocks, also a representation of God the Father, which had to be part of the altar, it is hard to understand that art historians have focussed on Salvator Mundi representations from other regions of Italy as a model for Leonardo, but not on the obvious: on 15th century Salvator Mundi iconography from Florence (which includes a representation of God the Father as well). We show a well-known work of art by Fra Angelico here; while we also are highlighting Salvator Mundi iconography in other media, but also from the 15th century: Saint Christophoros, for example, with Christ as the Salvator Mundi, was also represented in sculpture (one example in the Basler Münsterschatz; see above on the left), and Salvator Mundi iconography does show also in illuminated manuscripts from the 15th century, such as the Missale de Bonivard (Geneva).

(below I am reproducing my first contribution on this topic)

(9.7.2023) There are two reasons, I believe, why it might be worthwile to study medieval Salvator Mundi iconography. First of all Salvator Mundi iconography has a spiritual side (Christ appears giving a blessing), but also a political side (Christ appears holding a globe, which belongs to the insignia of a ruler). And hence it would be about to ask, whether our notions of the political and the spiritual can be applied here at all. And if yes, if we see, in the history of the Middle Ages, a constant and very basic mingling of the political and the spiritual which functions, in an almost natural way, as an instrumentalization of the spiritual in the service of politics (for which especially German art history has always tended to have a blind eye, since also art history, all-too often has functioned in the service of politics).

Secondly: if German art history was right to say (and to repeat, again and again) that Salvator Mundi iconography was the result of two iconographical traditions, the Vera Icon tradition as well as the Christ in Majesty tradition, mingling in Early Netherlandish art of the 15th century, what was the status of such pictures? And: Wouldn’t it be more appropriate to say that Salvator Mundi iconography had a revival in Early Netherlandish art, under the condition of painting becoming more realistic, naturalistic and even hyperrealistic, a tendency that also raises the question of what sense did it make to create such pictures that, still, had to be seen as representations and thus as artifical creations. And I am speaking of a revival, since Salvator Mundi iconography did already, as we will see, exist in medieval times (even if German art history was and is not able to see it) (picture above: sailko).

(Picture: GO69)

1) The Universe of Chartres

(Picture: Vassil)

(Picture: medieval mason)

In the universe of Chartres (see Favier etc. 1989) we also find Salvator Mundi iconography, but, as it is often the case in medieval art, things are not as they might appear at first sight.

Three representations of the Vièrge enjoy particular veneration at Chartres, among them the Notre-Dame-du-Pilier (above), which is basically a wooden sculpture of Madonna and Child, inserted into the architectural setting of Chartres. The Christ Child appears, as cannot be seen in the above picture, due to the drapery, as a Salvator Mundi, with orb. But although from the monograph by Favier we might learn that this sculpture was made in the 14th century (see Favier, p. 29), today scholarship seems to place it into the 16th century.

But there is another picture in Favier’s book: this very sculpture does also appear as crowned and being draped in cloth (as in the picture shown above), as was, or as still is the case on occasion of particular festivities. And in this picture the Vièrge does appear as representing the French monarchy, as is indicated by the lilies on the cloth (which is also covering the orb, so that it cannot be seen, in the above picture, that the Christ Child does appear as a Salvator Mundi). What we see in this picture is the use being made of the sculpture in modern times, but probably – as it was also customary in medieval times: the central figures of the Christian faith do appear, respectively are staged as supporters and supervisors of the actual rulers. And this is exactly the mingling of the spiritual and the political, as is already inherent in Salvator Mundi iconograpy, in which Christ does appear as the ruler of the universe, supervising the earthly rule of kings and queens, and emperors. Who, in medieval art, have Christ staged as legitimizing the earthly rule of kings and queens, and emperors, and this on the basis of the theory of the Divine Right of Kings.

At Chartres we may encounter the sources of later Salvator Mundi iconography, respectively the parallels of Salvator Mundi iconography (see pictures on the left and right): Christ in Majesty, or staged as judge, and also in the medium of sculpture. But also in the medium of stained glass; and we hence do find traces of medieval Salvator Mundi iconography, even if the Notre-Dame-du-Pilier is, or might be actually a 16th century work, and even if the use being made of this sculpture does only reflect, or emulate the use being made of such works of art in medieval times.

2) Pre-1019 Salvator Mundi Iconography

(Picture: sailko)

A particular handy way to study medieval art is the study of treasures, such as the treasures of cathedrals, since these treasures were being amassed over large periods of time, so that medieval art of many periods can be studied in detail, without all-too systematic study being necessary. Instead the example of one treasure, such as the treasure of the Basel Minster might be seen as one charming opportunity to study medieval art, if the comparison may be allowed: in a nutshell.

Salvator Mundi iconography does appear on the so-called Basler Antependium, the golden plate that was placed in front of the main altar. And this most famous example of medieval art modern scholarship tends to date in the pre-1019 period, since it is assumed that the Antependium did already exist, when it was presented to the Basel Minster by emperor Henry II. So what we have here is a reference point in the history of Salvator Mundi iconography, and the link to a ruler having Christ appear as the ruler of the universe, is also a reference point as to the mingling of politics and religion. We see Salvator Mundi iconography which is archaic and obviously has nothing to do with art blurring the line between representation and reality (as in later Salvator Mundi iconography, which, in this respect, is rather frivolous, in that it is constantly staging a quasi-real encounter of a beholder and Christ). Here it is about the representation of political theology which is also the legitimating power of a ruler and donator like Henry II, who has political theology appear in art, which, in retrospect does appear as one important reference point as to political theology as such. Christ does appear as a Salvator Mundi, the king of kings, by whose power also earthly rulers are legitimated to rule, but it is a ruler who, in the role of a donator, is the driving force behing that representation of medieval political theology, which also is rather meant to overwhelm than to explain what political theory is about. The splendour of gold, one might say, has, in itself, rather the function to overwhelm, to have something appear as unquestionable, which, in the view of modern men, might appear as politics disguised as religion, although there is probably nothing cynical about it, since social institutions do function as long people believe in the power of these institutions, and we cannot assume that medieval men could stand above these institutions, only using them cynically in the interest of mere power.

3) An 1423 Etching

Our third example of medieval or quasi-medieval Salvator Mundi iconography is a woodcut from the 15th century, and this representation of St. Christophoros carrying a Christ in the role as Salvator Mundi, is from the same period that, in painting, does see the aforementioned frivolously realistic revival of the Vera Icon tradition, a revival that raises the question of what theory of the image was behind this revival, if reality was staged in a picture so that a beholder could imagine himself in an encounter with Christ himself. This woodcut, obviously, belongs to a pictorial tradition that does not strive for hyperrealism, but rather could be seen as an embodiment of humility, in that Christ is shown giving a blessing, but it is not a blessing directed to the beholder, nor to a secular person in the picture (as in the Madonna Rolin), but rather addressing the saint. This is an example of Salvator Mundi iconography, heralding the age of the printing press, with books and pamphlets questioning also the role of pictures, and also and especially the role of depictions of saints, but while painting, in Early Netherlandish art, is embarking on the mission to represent reality convincingly, the woodcut per se is not embarking on that mission. It is an example of Salvator Mundi iconography that is rather embarking on questioning the Salvator Mundi revival based on the Vera Icon tradition, since this work of art does not stage Christ, but rather shows how Christ, being represented as the Salvator Mundi, is ›carried into‹ the age of the Renaissance in terms of an iconographical tradition being transmitted which the Renaissance was going to develop into an experiment of staging illusionary encounters, which might be seen as encounters with images, but were, probably, rather popular, due to these images, paintings, rather disguising their status as images, allowing a beholder to be carried away, due to overwhelming realism. And this is exactly what pre-modern debates and controversies over the status of images were about: the function of the image – as humble representation, or as the attempt to stage reality, by means of pictures, that had their own status as being artificial works of art forget – to become: most successful illusions of reality.

Selected Literature:

Jean Favier (with John James; Yves Flamand; photographs by Jean Bernard), Das Universum von Chartres. Die Kathedrale Notre-Dame, Stuttgart etc. 1989 [pp. 28f.]

Gude Suckale-Redlefsen, Die goldene Altartafel und ihre kunsthistorische Einordnung, in: Historisches Museum Basel (ed.), Der Basler Münsterschatz, Basel 2001, pp. 293-303

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS