M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES | FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS | HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION | ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

(Picture: Gisela M. A. Richter 1972, p. 17) Louise M. Richter (1850-1938) – a Diarist of the Morellian era (and beyond) |

(Picture of Brighton: artuk.com ; George Earl)

M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

This is not about art writing, but about the social world of attributing. Which means: This is about a social text: about the gestures, roles, mechanisms and opportunities of connoisseurship.

And for once: this is about a woman. A woman, by marriage, growing into this social world of attributing. And last but not least: it is about becoming (or not becoming) a female connoisseur in her own right.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM ONE) The ›Adelina Patti of Brighton‹

ONE) The ›Adelina Patti of Brighton‹

There is a connection between Louise Richter and Brighton.(1) And it has more than just an anecdotal bearing. In Brighton, being then in her twenties, Louise Richter spent about a year, living in Clarendon Terrace, Kemptown. And one has to imagine a young woman who was of German origins, but had spent her youth in Turkey. Her father, a silk producer, had died early. And here she was in England with her mother and her sister.

She had musical talents, and as one might now imagine, it was about marriage now (and therefore also about the image of the accomplished woman, that is: about social expectations and about dealing with expectations represented by near relatives, acquaintances and society at large).(2) In fact it was about marriage now, but her dream it was, then, to study singing at again another place, namely in Milan, and with (probably: Francesco) Lamperti. Her dream, in sum, it was to become a concert singer. But she would later come to the conclusion that she had missed her profession (and she said profession and not vocation), and that she had missed it, because she did in fact marry.

In England in the 1870s she was introduced to society. There was a young promising German-born scholar she met nearby London, in Hampstead Heath; one day the two played chess after dinner, and the young scholar did propose to her;(3) they got married, and Louise Richter, at the time, wanted this too (she actually did support bold biographical decisions at times and also later as a married woman, and this was a bold move). She wanted this too perhaps because the young scholar may have seemed to be promising. But what exactly is a promising scholar? Someone who is expected to move one day into an institutional position, to provide security as a professor, curator, or as a museum director. And Jean Paul Richter, this was the name of the young scholar, actually lived all his life with this expectation. Only that he never lived up to that expectation. In fact, he never moved into an institutional position. Because he was not able to. Not willing to. A combination, probably, of both.

But he did provide security, which means: in his way. What now was to follow was the life of a family inside the European culture of connoisseurship. Partly adventurous, partly even spectacular. A transnational life, rich, but also torn, distracted. A life in England, Italy, Germany, France. A life, Louise Richter also, in late years, tried to be thankful of. She tried. And Brighton, to come back to the initial connection, then meant to recall the state before everything had begun. It meant to recall the moment in time when the future had seemed to be open. No doubt, she had been able to further develop her musical skills; and she probably had been able to become a professional singer. There had been Adelina Patti, an opera singer of the day, admired also by Louise Richter. And to come full circle: Louise Richter did recall, later in her life, that, at Brighton, aquaintances had called her ›the Adelina Patti of Brighton‹.(4) And this she recalled later, at a time when musing, as a married woman, about her status as a married woman, and about the one turn in life, when, now in hindsight, she was questioning that very step.

Adelina Patti in 1874

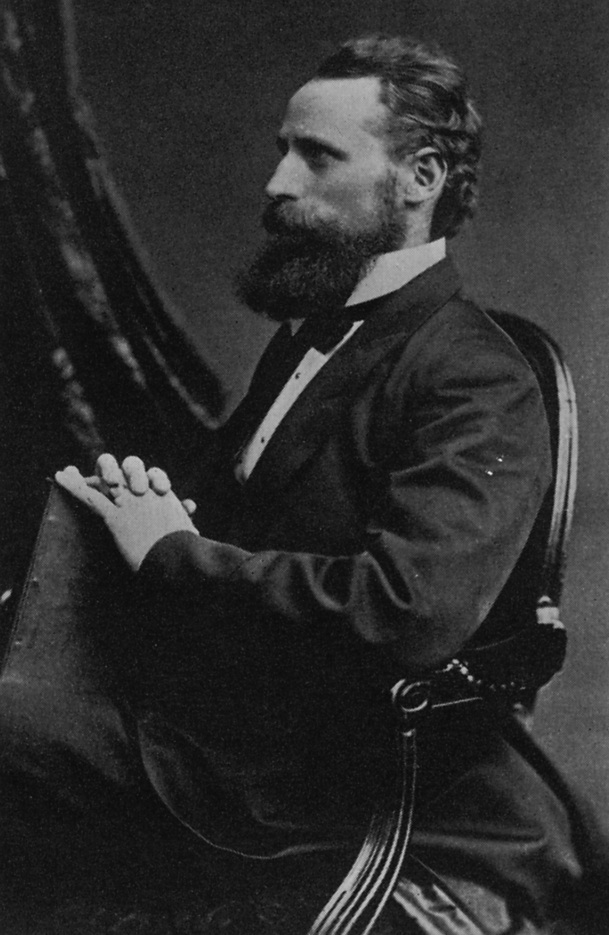

Jean Paul Richter (1847-1937)

(picture: Giulio Bora (ed.),

Giovanni Morelli – collezionista di disegni.

La donazione al Castello Sforzesco,

Cinisello Balsamo 1994, p. 91)

M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM TWO) The Richter Family and Connoisseur of Art Giovanni Morelli

TWO) The Richter Family and Connoisseur of Art Giovanni Morelli

From an history of art history perspective one must say that the life of the Richter’s was now to become spectacular. Jean Paul Richter, who first had embarked on a career in Christian archeology, was to become the model pupil of connoisseur of art Giovanni Morelli;(5) and all Morelli could achieve, in art connoisseurship, and rather late in his life, had much to do with the Richter family. Because Morelli, who does represent the ambition of a scientific ambition in connoisseurship, paradoxically was lacking scientific discipline, endurance, patience. And he needed someone to assist him and to support him like for example another connoisseur, Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, had needed the cooperation of Joseph Archer Crowe. And for Morelli this man was Jean Paul Richter who, at the end of the 1870s and as an apprentice in art connoisseurship, was seeking for the master’s guidance. But this is not about this two men in the first place: the actual reason why one should speak on the Richter family within an art historical context, and on Louise Richter in particular, is that both of the Richters were diarists.(6)

It is certainly true that Louise Richter was also the first to translate Morelli into English, a little helped by Lady Eastlake in the beginning,(7) but it’s a deliberate choice to call her a diarist in the first place. She did not identify with the Morellian approach to connoisseurship as much as her husband; she did like Morelli tremendously as many people tremendously did like Morelli who was a warmhearted, in general noble and hence very aimable character; and during the 1880s there really was a symbiotic relation with Morelli who often stayed with the Richters and also was godfather to one of the Richter children. But her diaries, one has to say, were more important to her on an existential level than any of her other writings in the genre of translation, of fiction,(8) art history or of guide books.(9)

In sum we have this body of sources left by a family that lived right in the center of all that is associated with the Morellian school; this family provided us with diaries for more than three decades; and from this body of sources, the Richter diaries, a male and a female voice do speak. And this independently. Moreover: from a certain moment in time the female voice, a compassionate and unpretentious voice, does begin to speak critically of everything she experienced. And resulting from this is a particular depth of focus: two human beings speaking of more or less the same things, their common biography in the culture of connoisseurship, but from slightly or, at times, radically different angles that, of course, reflect also and very graphically, and also in their way of writing itself, their respective roles.(10) And from a certain moment in time Louise Richter was beginning to question everything. Her role, her position as a woman, and also what she experienced and observed inside the culture of connoisseurship.

What had happened was that Louise Richter, after some very happy years and in the mid 1880s, began to feel being entrapped in her role. And she says very precisely why: In her wish to achieve something artistically and intellectually – and this beyond here role as a mother and as a wife – she felt not being enough supported by her husband. And now she was recalling that, when she had lived in Brighton for about a year, she had known what she had wanted: to become a concert singer, and one had not allowed her to follow her way. And this not having been allowed – she attributed the responsibility to her mother – she tended to interpret as the one initial wound now, and the pattern, she felt, now was repeating. One did not allow her, or not enough to pursue projects in writing, or to pursue art studies more intensily, because to a certain degree she was able to combine all that. She was writing, also in a literary sense, she was studying art, but still she felt limited, and not enough supported by her husband who apparently could not bear the thought that the children (the Richters had four) were not being looked after. While Louise Richter seems to have seen this more relaxed, and on the other hand felt being wounded again, because her husband, at the same time, obviously did support other women in their respective intellectual and art historical ambitions, like for example Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes;(11) and it seems even that he admired these women just for such ambitions.

As a consequence, particularly in the 1890s when the Richters lived in London, anger accumulated in Louise Richter. And one can feel this physically, as a reader of her diaries, the anger, but also the new verve that resulted from becoming angry. And as a result she was seeking for ways to express herself, for ways to win more independance.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

Three) The Act of Attribution – pragmatism, symbolism, realism

Three) The Act of Attribution – pragmatism, symbolism, realism

I am tempted here to speak of particular scenes here, since the Richter diaries really allow to do microhistory. There is great richness of detail, and it is possible to zoom into particular scenes, like for example – if we go back in time again – a 1887 visit of Morelli with his entourage at Hampton Court, where all the school children of London seemed to have gathered on that particular day, which was, beside that, also to become an important day for Giorgione scholarship, but also was memorable for the subsequent picnic with Morelli at Richmond park.

Microhistorical Insights or One Day in Giorgione Scholarship(12)

A question mark in Giovanni Morelli’s 1891 volume on the galleries of Dresden and Munich shows that he actually never gave up his reserve as to attributing the Hampton Court Shepard with a Flute (Apollo) to Giorgione, as well as his pointing out that he had seen the picture only in ›dim light‹.(13) And in sum, in a very characteristic turn, he declared that he was unwilling to take any responsibility for this attribution (that he however tended to support).(14)

This statement, in its ambiguity, a most characteristic ambiguity, can be read against the two narratives from the Richter diaries, displaying that dim light was not necessarily a problem on that particular day, but rather the fact that – to the surprise of the group of visitors that had grouped among Morelli, and not to the liking of particularly Louise Richter – Hampton Court (including its galleries) was, as mentioned, full of children – and thus noise and much distraction.(15)

The schedule of the day can be reconstructed to some detail on basis of the two accounts;(16) but important remains also what is not stated at all therein: namely that the Richters were not at all disinterested as to Giorgione attributions by their master and mentor Morelli, since the family was in the possession of the Portrait of a Young Man that, some years later, was to enter the Berlin gallery as a Giorgione,(17) and for this attribution Jean Paul Richter was, much later, to claim responsibility (although the main argument to back it up might have been chiefly ambiguous statements by Morelli).(18)

Thus: Any Giorgione attribution must be regarded to have worked, in this particular context, notwithstanding the noise and distraction, as an inpulse or stimulus to think the oeuvre by Giorgione in a particular way. And the characteristic Morellian ambiguity (19) – that seemed to regard the Hampton Court picture as another reference for further attributions, that is: as another possible reference picture – left any connoisseur with much freedom to think that oeuvre in the one or other way (highlighting Morelli’s asserted or his sceptical side). And although it was never stated: Richter must have immediately made a connection between the two pictures, all the more both do show a young man (that one may regard as sensitive) with a comparable hairstyle or ›mane‹ (zazzera). However it is worth noticing that also in the diary of Jean Paul Richter the Hampton Court ›discovery‹ is marked with a question mark. But on the other hand it was in October of that very same year that Jean Paul Richter spoke, in his diary, for the very first time of his »Giorgione«, the mentioned portrait in the Richter’s home that actually, since she had gotten it as a birthday present, owned by Louise.(20)

As to that particular day in July, that memorable day in Giorgione scholarship, the diary of Jean Paul Richter shows him very focussed on exterior facts. While the diary kept by Louise shows her more concerned with herself and her own experiencing,(21) but nonetheless also observing the scenery at large, and particularly taking notice of the fact that her husband (as well as her son Sandro), also on that particular day, had been focussed passionately on attributions and attributing.(22)

She was, although as if seeing through a certain haze, recalling and noting – in retrospect – what had been going on also on that level of attributing, that is: she was, routinely, taking notice of that practice she was surrounded by virtually every day of her life at home. And thus she seems not at all to have been unaware that it mattered what had been discussed on that particular day among the connoisseurs (although also this has to be read between the lines), and in particular as to what Morelli, the unquestioned master, had ›believed‹.

Since indeed, it was to matter for her and for her family some years later, since only the sale of the picture today at Berlin – as a Giorgione –, and together with another major sale, enabled the Richter family to climb the social ladder at the beginning of the 1890s, namely to move back from Italy to London in 1892, to buy a house in London in a upper middle class area, and to live, at least for some time, on the fortune, intimately connected with a picture that still generally is being seen as a Giorgione (although it is rarely or actually: never stated why exactly).(23)

That Morelli had remained – for whatever reasons – ambiguous as to the Hampton Court picture seems, by the way, to have rather escaped scholars’ notice. In fact: one does read that he had (already in 1880) insisted on that particular attribution,(24) although this means turning facts – by ignoring his statements of 1891 – to the opposite.

This ›one day in Giorgione scholarship‹ that shows Louise M. Richter more as an observer I’d like to confront now briefly with another scene, from the 1890s, that shows her more active, more energetic and almost like a female connoisseur, that is: at the brink of entering this embattled, agonistic and hardly regulated field of connoisseurship on her own.

On occasion of a visit of the picture gallery of Berlin (25) she had felt that a picture was misattributed, and with her newly won verve, resulting from her above mentioned rage, with her disrespect also for pretentious connoisseurial chitchat (she had heard this enough at her own table), and with her confidence also that resulted from her studies (I want to say deliberately: in the shadow of her husband) she was now saying: this painting is mislabelled (as ›school of Verrocchio‹), I know what it is (Ghirlandaio), and I really would like to prove it.(26)

And with saying this, sticking also to the very rational approach of wanting to prove and not just to claim it, we see her exactly on the brink to enter what was the actual profession of her husband (who was always ›dressing‹ as a scholar, but tended to dissimulate the fact of living on the ›business of attribution‹, something that, in the 19th century was also associated with some shame and done often rather out of necessity and for pragmatic reasons).

And at least or: only in a symbolical gesture Louise Richter was now to repeat exactly this. Not because there was an economical need to, one might say, but because this was a way to express independence, self-confidence, expertise won by observing (observing her husband, but also other connoisseurs, and also, to some degree, taught by Morelli, who had made the point that connoisseurship was not about claiming something, but about showing, explaining and proving, about making something verifiable). And such entering of the field could result, she had seen this with her husband, in winning of independence and social status, but such entering, as she knew well as well, meant and required moves into a more public and agonistic field, where it was and it is about winning, defending and also losing reputation, status, definatory power, while it is – today no less than at her day – not particularly clear how exactly one does attain definatory power, that is: based on what exact knowledge and skills.

In some sense, with her move, we see the Richter family really becoming a genuine microcosmos of roles. Here were the parents, a professional connoisseur, and here was Louise Richter thinking about attributing and at least turning to connoisseurship and writing on art herself – in that she wrote two guidebooks, on Siena and on Chantilly and the Musé Condé (27), at a time when also her two daughters began to articulate their wishes for a professional career: one daughter, Irma, as a painter, and the other, Gisela, as an art scholar, archeologist and curator, and it was Gisela Richter who, in some ways, did fuse and realize ambitions of both her parents: in that she could study (in Cambridge) and in that she moved into a position inside the museum world, namely the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where she is still being regarded as a role model and pioneer. And where she also established as a scholar and author of important handbooks on the subject of Greek art.(28)

Her mother, Louise Richter, undertook some steps in that direction, symbolical and also real steps, but possibilities, one must say, remained restrained (or she, in some sense wisely, restrained these steps), and she certainly did not establish as a woman connoisseur, in that she became known to a specific public and in that her expertise was sought after, and in that her status was confirmed.

She did, nevertheless, publish articles, casual works, and in genre: informative articles, in a number of art historical journals, French, German and English journals;(29) she did also catalogue the picture collection of a woman friend, and this was, significantly, the wife of the one patron of her husband (Frida Mond, wife of industrialist Ludwig Mond, who was also her husband’s patron, one must add, because two women, Louise Richter being one of them, had helped to arrange this partnership, to the benefit of both families, the Richters and the Monds, two German-English families, cosmopolitan families, but also torn between the nations).(30)

But this cataloguing happened in private, and of more vital, of more existential importance were in the end and as said her diaries and being a diarist to her. And she was in a way speaking to herself, and to her daughters, but in the end explicitely also to posterity.(31)

I’d like to conclude by warmly recommending these diaries – and the Richter diaries as a whole – as a source (now being kept in the Metropolitan Museum), a source that allows to do microhistory, to chose scenes and to analyze them in detail, but also to do more structural, typological, more sociological analysis, and of course allow to combine both. With at least three generations of a family within one frame, with a crucial point in the development of connoisseurship as a field coming into the frame, with Morelli being the advocate for scientific standards; and with many a scene that would be worth to be studied more in-depth, just because it is about more than about impressionist scenes or fragments from the life of a family. But about what it is exactly to be and to establish as a scholar or as a connoisseur or as both, about how to accumulate authority, reputation, status; but also and generally and perhaps above all: about how to live according one’s wishes. As a man, as a woman. And here: by means of connoisseurship, and within a professional field as unregulated as connoisseurship.

I want to conclude also with a particular scene that actually shows Louise Richter as a speaker in the actual sense of the word: because in Rome, in 1908, she appeared as a speaker at the First Italian Congress of Women.(32) As the only foreign speaker apparently being able to speak Italian, and she was speaking on the subject of the Lyceum Clubs. That is: on the issue of having, of finding or organizing a social space, a sphere of mutual assistance to the benefit of women. And that she appeared as a speaker at this particular congress must also be seen as an outcome of a transnational life, partly torn, partly agonistic, but partly also spectacular, and on the whole very memorable, a life based on applied connoisseurship and inside the culture of connoisseurship. Lived in relative independence, but also a family’s biography torn by harsh and partly very bitter inner struggles.

![]() Annotations:

Annotations:

1) For Brighton (and also for other biographical details mentioned in this first section) see Louise M. Richter, Random Reminiscences of my Life, unpublished manuscript [no pagination]. This source, as well as a stock of diaries (see below) and other sources, are now part of the Gisela M. A. Richter archives, kept by the Onassis Library of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. A portrait of Louise M. Richter is included in my biography of her husband Jean Paul Richter (see Dietrich Seybold, Das Schlaraffenleben der Kunst, Paderborn 2014, pp. 81ff.), which in many ways is also a portrait of the Richter family. Secondary literature on Louise M. Richter, apart from this mentioned work, and apart from this essay, is lacking. – The basis of this present essay had been prepared in 2015 for oral presentation at University of Sussex. The character of the presentation has been kept. I would like to thank Francesco Ventrella and Meaghan Clarke for their generous cooperation.

2) For the motif of the accomplished woman see Ann Bermingham, The Aesthetics of Ignorance: The Accomplished Woman in the Culture of Connoisseurship, Oxford Art Journal 16 (1993), pp. 3-20.

3) For more details (and detailed references) see again my Jean Paul Richter biography (as mentioned in reference 1).

4) See Louise M. Richter, Diary No. 18, 24 July 1923.

5) For Morelli see now Dietrich Seybold, The Giovanni Morelli Monograph, e-publication: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/TheGiovanniMorelliMonograph, Basel 2016, which includes a visual biography as well as a platform dedicated to the connoisseurial practices of this foundational figure of scientific connoisseurship. – See also some of the more recent contributions as for example Luke Uglow, Giovanni Morelli and his friend Giorgione: connoisseurship, science and irony, in: Journal of Art Historiography 6 (2014), pp. 1-30, and Jaynie Anderson, The restoration of Renaissance painting in mid nineteenth-century Milan. Giuseppe Molteni in correspondence with Giovanni Morelli, Florence 2014.

6) One may now, as mentioned, consult the extant Jean Paul Richter diaries as well as the diaries kept by Louise M. Richter in the Onassis Library of the Metropolitan Museum. I am quoting the diaries of Louise M. Richter by number. The diaries of her husband have the form of desktop diaries, corresponding to the calendar of a respective year, while Louise M. Richter never used such pre-formatted, but always empty notebooks.

7) For this particular information see the letter Louise M. Richter to Giovanni Morelli, 4 August 1882, archive of the Bibliotheca Hertziana, Rome, Nachlass Jean Paul Richter. See also my Giovanni Morelli Monograph, chapter Visual Apprenticeship III [no pagination]. For the translation see Giovanni Morelli, Italian Masters in German Galleries. A critical essay on the Italian pictures in the galleries of Munich – Dresden – Berlin, London 1883.

8) In 1886 Louise M. Richter published a novel (Melita. A Turkish Love Story, London 1886) which was dedicated to Henriette Hertz (who, on her part, had been publishing fictional writing). For Henriette Hertz, the family of Ludwig and Frida Mond, see again my Richter biography, but also a particularly thorough and particularly committed thesis: Julia Laura Rischbieter, Henriette Hertz. Mäzenin und Gründerin der Bibliotheca Hertziana in Rom, Wiesbaden 2004.

9) See further below for references.

10) On the whole one might say that the male way of writing, here, reflected the need to control and to organize life and was focussed on the organization of life, the daily events, contacts, administration at large; while the female way of writing, again: here, was much more focussed on meaning, self-reflection and in that a sort of critical soliloquy. Said this, one might of course ask as well, if and how Jean Paul Richter reflected on his life and debated with himself, and also if and how Louise Richter had other strategies to organize life. It is, however, a distinct character of the sources, that brings up, after this character has been analysed, these questions.

11) For Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes see the upcoming publications by Francesco Ventrella. Some references to mentionings of her in various sources are also included in my Richter biography and my monograph dedicated to Giovanni Morelli.

12) I am presently considering to collect various such scenes under this very title ›One Day in Giorgione Scholarship‹.

13) See Ivan Lermolieff [Giovanni Morelli], Kunstkritische Studien über italienische Malerei. Die Galerien zu München und Dresden, Lipsia 1891, p. 292 (question mark) and p. 285f.

14) Op. cit., p. 286.

15) See Jean Paul Richter Diaries [Diary of 1887], 28 July 1887; Louise M. Richter, Diary No. 4, 30 July.

16) Jean Paul Richter: »Früh in 2 Wagen über Richmond nach Hampton Court. Picnic im Park. Giorgione? Correggio, Lotto, 4 Dosso, Mantegna. Morelli mit den Damen [und] Miss Ffaulkes [sic; Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes]. Herr [Ludwig] Mond zankt Sandro [Richter]. Diner bei [probably: Charles B.] Curtis im Langham [Hotel]. Dessen Frau. Er hat 1 Velasquez & 1 Murillo. Zeitig zu Bett. [›Early in the morning with two carriages via Richmond to Hampton Court. Picnic in the park. Giorgione? Correggio, Lotto, 4 Dosso, Mantegna. Morelli with the ladies [and] Miss [Constance Jocelyn] Ffoulkes. Mr [Ludwig] Mond wrangles with Sandro [Richter; his little son]. Dinner with [probably: Velásquez scholar Charles B.] Curtis in Langham [Hotel]. His wife. He has got 1 Velasquez & 1 Murillo. Early to bed.‹]« – Louise M. Richter [30 July]: »Einen herrlichen Tag verbrachten wir vorgestern in Hampton Court! Wir fuhren hier ab gegen 10 Uhr in 2 grossen Equipagen. Das schönste Wetter begünstigte unsere Fahrt. Am Langham Hotel holten wir Senatore Morelli ab, u[nd] nun gings durch die Londoner Strassen, durch Kew & Richmond unserem Ziel zu. Ich sass mit Morelli & Frl. [Henriette] Hertz in einem Wagen[.] – Das Gespräch drehte sich immer über Kunst. In Hampton Court angekommen sah ich zu meinem grossen Erstaunen massenhaft Kinder in dem Garten sich drängen[.] Es waren viele Schulen Londons oder der Umgegend[,] die dahin eine [Garten] pleasure-party arangiert hatten. Diese wurden nun auch in die Galerien zugelassen[.] Es war schrecklich! Das Geschrei & und der Lärm. Wir trachteten jedoch so viel als möglich die Bilder zu geniessen. So erfreuten uns nun gleich 2 herrliche Tintoretto (1 Echter) & ein Portrait von Bas[s]ano. Ein gleich kleines Bildchen von Bassano wurde von Sandro[,] der mit uns war[,], als solches erkannt, indem er ausrief: Sieh[,] Papa[,] das ist ein Bild so wie wir eines haben[;] das kl. Bildchen[,] das über dem Klavier hängt. Morelli meinte[,] ein Giorgione zu entdecken in einem schönen Jünglingskopf. Auch ein Correggio[,] die ›lesende Katharina‹ wurde [unreadable; probably: von dem] JPaul entdeckt[,] da das Bild anders hiess. Ein schönes Dürer Portrait & ein Holbein ist in den Nebenzimmern. Ein nie zu vergessender Titian, Portrait, 2 Lottos, 2 Dosso Dossi. – Die Heimfahrt unterbrachen wir, um unter den wuchtigen Bäumen von Richmond Park einen Imbiss einzunehmen. Abends fuhren wir nach dem Langham Hotel[,] um mit Curtis zu speisen; seine Frau ist sehr liebenswürdig & hat schöne Kinder. – [›A delightful day we spent the day before yesterday at Hampton Court! At about 10 o’clock we were off here with two large equipages. The most beautiful weather fostered our trip. At Langham Hotel we picked up Senatore Morelli, and off we went through the streets of London, through Kew & Richmond, towards our goal. I was in one carriage with Morelli and Miss [Henriette] Hertz. – The conversation always turned on art. After arrival at Hampton Court to my huge amazement I saw masses of school children clustering in the garden. Many schools of London or of the surrounding area had arranged a garden pleasure-party there. These were now also allowed to walk the galleries. It was horrible! The yelling & the noise. Yet we aimed at enjoying the pictures as much as possible. And thus we were delighted by two marvellous Tintoretto (1 genuine) & one portrait by Bassano. A picture of similar small size was recognized as such by Sandro, who was with us, in that he burst out: Look, Dad, there is a picture like the one we have[;] the little picture that is hung above the piano. Morelli believed to discover a Giorgione in the beautiful head of a youth. A Correggio, the ›reading Catherine‹, was discovered [unreadable; probably:] by JPaul, since the picture was named otherwise. A beautiful portrait by Dürer & a Holbein are in the siderooms. A Titian, portrait, never to forget, 2 Lotto, 2 Dosso Dossi. – The drive home we interrupted to take a light meal under the mighty trees of Richmond park. In the evening we drove to Langham Hotel to have dinner with Curtis; his wife is very aimable & and has beautiful children. –‹]«

17) For the picture see for example Terisio Pignatti/Filippo Pedrocco, Giorgione, Munich 1999, p. 140f.

18) See Seybold, Schlaraffenleben, pp. 158ff. for an extensive account as to the attributional history, as far this history can – due to lacking extensive and transparent protocols – be reconstructed at all.

19) For many examples and also expertises by Morelli see now my Giovanni Morelli Monograph (as mentioned above).

20) Compare Seybold, Schlaraffenleben, p. 163.

21) To understand Louise Richter’s general mood it is important to know that the Richter’s had lost a newly born child, Melita, in 1886, the year before, due to a suddenly occuring illness. Particularly Louise Richter, according her own words, never got fully over that tragic event. See also her privately printed memoirs (Louise M. Richter, Recollections of Dr. Ludwig Mond, London 1910), a booklet which provides, despite of its title, rather recollections of the Richter family’s life.

22) Compare the texts given above.

23) This particular criticism – the general lack of transparency within a culture that nonetheless claims to be a scientific culture – is more elaborated in my Morelli monograph.

24) Pignatti/Pedrocco, op. cit, p. 180.

25) See Louise M. Richter, Diary No. 7, 6 June 1896.

26) »[…] was ich sehr gerne beweisen möchte [›[…] what I would love to prove.‹].« – The painting must be one of the two pictures that the Berlin catalogue of 1909 had labelled as ›Schule des Andrea del Verrocchio‹, either a Christus am Kreuz, die hll. Antonius der Eremit und Lauretius, Petrus Martyr und der Erzengel Raphael mit dem jungen Tobias (No. 70 A) or a Krönung Mariä (No. 72). See Königliche Museen zu Berlin, Die Gemäldegalerie des Kaiser-Friedrich-Museums. Vollständiger beschreibender Katalog mit Abbildungen sämtlicher Gemälde, Berlin 1909, p. 42f. – For a female art historian questioning an attribution going back to no other than Giovanni Morelli see Maude Cruttwell, Luca Signorelli, London 1899, p. 6 with note 12.

27) Louise M. Richter, Chantilly in History and Art, London 1913; ibid., Siena, Lipsia 21915 [1901]. – The Chantilly study, impressive in its volume, does read as a sober and informative guide, and one may suppose that Louise M. Richter also attempted to emulate the scholarly style of her husband (who, particularly in English circles, was perceived rather as being a dry as dust). On a biographical level, however, the year long work for this volume, which was published at the eve of the First World War, had much to do with reverie and escaping from the then miserable state of the Richter marriage. The couple had virtually split, due to Jean Paul Richter chosing to live in Italy again after the turn of the century and to work on a study on the mosaics of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, helped by a female assistant (Alice Cameron Taylor). And therefore the Chantilly adventure had also to do with Louise M. Richter chosing, on her own part, to embark on an intellectual (and in some way: romantic) adventure and to match her husband on a symbolical level. In sum: although hardly any reader could know this – the very existence of that very book had, for the author, a very significant and symbolical meaning as a demonstration of her own identity and self-confidence. – The copy of the book in my possession bears a handwritten dedication by the author to no other than art connoisseur Max J. Friedländer.

28) For an overview see Joan R. Mertens, The Publications of Gisela M. A. Richter: A Bibliography, in: Metropolitan Museum Journal 17, pp. 119-132.

29) See Louise M. Richter, The Collection of Dr. Ludwig Mond, in: The Connoisseur 4 (1902), pp. 75-83 and 229-236; ibid., Old Masters in Burlington House, in Gazette des Beaux Arts 31 (1904), pp. 423-431; ibid., The Exhibition of the French Primitifs in Paris, in: The Studio 32 (1904), pp. 191-197; ibid., A lost altarpiece by the Maître de Flémalle, in: The Burlington Magazine 13 (1908), pp. 161-162; ibid., French sixteenth century portraiture with special reference to the new François Clouet in the Louvre, in: Monatshefte für Kunstwissenschaft 2 (1909), pp. 356-367; ibid., Ein längst verschollener und wiedergefundener Botticelli, in: Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, [new series] 24 (1913), pp. 94-96; ibid., The Mond Collection for the Nation, in: The Connoisseur 66 (1923), pp. 129-137.

30) See again Seybold, Schlaraffenleben, pp. 118ff. and 213ff., as well as my history of the picture collection of Henriette Hertz (Dietrich Seybold, Il desiderio di un »brano di vera anima dell’umanità«. Per una breve storia della collezione Hertz, in: Sybille Ebert-Schifferer/Anna Lo Bianco (eds.), La donazione di Enrichetta Hertz 1913 - 2013, Cinisello Balsamo 2013, pp. 27-43).

31) See Seybold, Schlaraffenleben, p. 82f., with particularly note 23.

32) See Louise M. Richter, Diary No. 11, 3 May 1908. – This particular congress has recently been made subject of a special study: see Claudia Frattini, Il primo congresso delle donne italiane, Roma 1908. Opinione pubblica e femminismo, Rome 2008.

Inside Hampton Court Palace

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS