M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

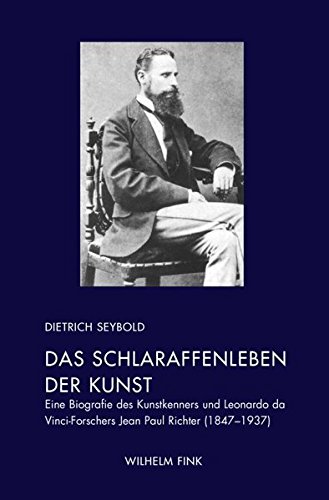

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

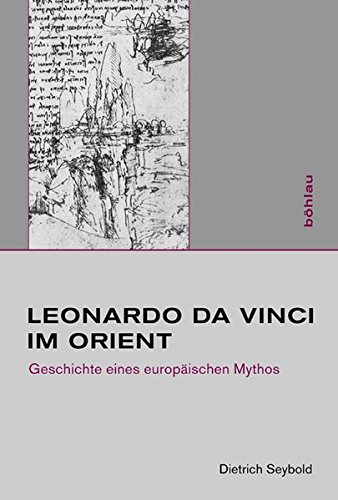

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

SPECIAL EDITION

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Some Salvator Mundi Revisions  |

Here comes the fifth season of our Salvator Mundi observations and reflections (today is Friday, 15 November, 2019). This time we focus on recent (or upcoming) revisions in the intriguing field of Salvator Mundi studies. Which is: here comes a menu of ultra-specialized avantgarde studies, mixed with some reflections on ›Celebrity Art‹ and its collecting. Is this about creating a new field, a kind of ›Celebrity Art History‹? I don’t think so. It is more about observing contemporary culture in all its glory and shallowness, while also investigating the depths of history. Brief: it is about being ›absolutely modern‹.

Christ and Antichrist:

We live in apocalyptic times. More precisely: in times that, again, produce apocalyptic rhetoric. I will not discuss scenarios as to climate change and its consequences here. It is enough (in our limited context) to remind that we hear of a ›last generation‹ and of the fear of ›extinction‹, as well as of ways to ›save‹ the world (by preventing accelerated climate change or other measures). And these patterns of speak and thinking have a history that goes back rather far, and no matter if implied or not, we can also observe an interaction between old and new patterns of apocalyptic rhetoric, and this might be called an interaction of postmodernity with history. And believe it or not: this postmodern context might also affect the way we see and perceive pictures of the Salvator Mundi, the Saviour or Redentore (Salvatore), and especially the way we see and perceive slightly (or more brutally) altered Salvator Mundi versions, slightly (or more brutally) altered depictions of Christ.

The Antichrist is a figure that appears in apocalyptic literature, and this literature makes clear that one had (or we have or will have) to face the problem of actually distinguishing the Antichrist from Christ. The false prophet from the right one. Because the Antichrist appears as Christ, disguises as Christ and claims to be the right prophet. The visual arts of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, however, remained very reluctant to enter this dangerous discourse. We have depictions of the Antichrist, but the visual arts are rather decided to make clear who is who.

If we now turn back to the contemporary scene, we will see that we are actually witnessing a very secular discourse, that however, functions very similarly as the discourse of Christ and Antichrist in traditional apocalyptic literature: the world seems to be immensely interested in the question of which Salvator Mundi picture, which saviour, is actually the right one (by Leonardo) and which ones are the ›false prophets‹ (that are not by the all-exceptional master). And while this is happening (and while all this has made one candidate all known, due to its exorbitant price tag), many people feel also inspired or compelled, to add their own Salvator Mundi versions to the already exorbitantly large ›swarm‹ of Salvator Mundi pictures. And some of these new productions now seem to be decided to re-enter that old traditional apocalyptic discourse, in that they remodel the now almost all-known version into obviously Luciferian ones, but also into versions that raise the suspicion if they are not rather depicting the Antichrist than Christ (because slight alterations also uglify the image, change the expression of the face, especially the eyes, and call up other associations). And we come full circle.

Because this is now something the visual arts of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, as I said, did not really dare: to raise – visually – the question if we face, in a seeming depiction of Christ, not rather the Antichrist (who disguises as Christ). And we see that the contemporary scene, while we might call it postmodern, might also be called: still rooted in very old patterns that are inherent to our cultural traditions, if we are aware of it or not.

Discourses are overlapping here: some secular (infected by capitalism, which is also rooted in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance), some pre-modern, and these discourses are producing interferences. Think for example of Christ’s blue garment and the exorbitantly expensive pigment of lapislazuli that was used to produce it: Is this rather about spiritual devotion or about conspicious consumption (or about both, because one is the mean to show the other) to use a large amount of lapislazuli? And another question? Is the seeming splendour of blue indeed for real? (And not the effect of some Luciferian blending of Lapis and some or rather much less expensive quartz?)

Corpus Cranach or: 23 Solutions to a Problem:

The Basel version

Here is the idea for a novel: there is this sloppy, late 20th century contributor to the Encyclopedia Britannica. He’s banned from Wikipedia, but this does not bother his superior (because he does not know of it). But since this contributor lives precariously (he is also a frustrated writer) he has to write about lots of stuff. Since he is also proud and disdains his (even more sloppy) superior, he now starts to invent things, to mix periods creatively, and to link things by chance. And since factchecking has also become too expensive at the dawn of the New Milennium, no one takes notice.

Now 500 years later: a rather mediocre historian stumbles over framents of the spectacularly sloppy (but also creative) archives of this rather sloppy late 20th century contributor to the Encyclopedia Britannica. And misunderstands everything, taking everything for real and even attributes Star Wars weaponry to the Middle Ages. And this rather mediocre historian sees his chance by exploiting his find, calling it The Plans of God, since he also thinks that the fragmentary archive preserved the very DNA (or whatever they will call it then) of our late 20th century civilisation. He thinks that this mediocre, precariously living guy at the dawn of the Milennium actually had invented everything that he wrote about: therefore – The Plans of God.

Now the third plot (we cut to and fro between three plots): On another planet the whole civilication found in the archive is rebuilt. Since there are only fragments, much is also added, improved and so on. And a dark-voiced narrator finally raises the question, what this all might mean as to the beginnings of our 21st century civilisation.

What do I want to say with this parable?

Well, there is an inbuilt, inherent flaw to the Leonardo business. The misunderstanding that Leonardo da Vinci invented everything that we see in his papers. But things are more complicated. Leonardo also collected ideas, inventorized and, yes, even linked periods creatively, since he imaginatively also re-designed and visualized antique weaponry, about which he ›only‹ had read. One might say that there is something of the ›Encyclopedia of the Renaissance‹ to Leonardo. But the world tends to attribute every idea to himself, and when machines are rebuilt, it does happen that engineers, more or less secretely, improve the machines, so that they might work (if the machine actually do work does not interest the Leonardo infotainment world, the main thing seems to be, that some all-superior can be admired, but from a safe distance).

And there are even inbuilt distortions to Leonardo-scholarship: Because even professional Leonardo scholars tend, all too often, to stare at Leonardo alone. To the effect that they do not realize that Leonardo was not the only person in the Renaissance who thought about this or that. Optics for example. Nor do the audiences of infotainment-oriented Leonardo scholars do realize this bias.

And now I come to the point: we have a debate if Leonardo actually did realize what he knew of optics in a Salvator Mundi picture. As to the Abu Dhabi Salvator we face the question, for example, if the garment, which is seen through a glassy (or crystal) orb, is rendered – as if seen through a glassy material. Do we detect the respective distortions or not? Did the ›Master of the Salvator Mundi‹ prepare for such effects to be realized visually (which we could perhaps detect by using IRR), and did perhaps the hand that actually did execute those parts of the painting not think about actually realizing such effects (so that 21st century restoring had to improve – but why on earth, not restoring digitally, if you are restoring experimentally?)? Questions over questions.

What I would like to mention here is, that Dürer had prepared to render such distortions (see his unfinished Salvator Mundi in the Metropolitan Museum of Art). And Agostino da Lodi (or the hand who worked in his Supper at Emmaus) definitively was interested in how bread was looking if it was seen through round glass (and even: through wine). And this was one of the Leonardeschi.

Bread seen through glass and through wine

Orb of the Kimbell version

And now I come to my final point: because I recently discovered that Lucas Cranach and his workshop – Northern Renaissance, one might say –, while producing renderings of the Judgement of Paris, did replace the notorious apple with a glassy sphere. And since 23 Judgement of Paris versions are left that can be associated in whatever way to Cranach and his workshop, this is not only an intriguing parallel story to the story of the Salvator Mundi ›swarm‹, but also a study material as to the question how a double problem (how to render a glassy material, and perhaps also how to render the material that is seen as if seen through glass) is solved. 23 times differently.

And now we are arriving at the final point, where Leonardo da Vinci might be actually, if it is convenient, be contextualized.

Detroit Disaster, The:

As historians we have learned to ask the question: who exactly was it who did built the pyramids? And: Who exactly was it who fell the tree? In 1569.

Well, we don’t know, but 1569 is now the date. The date the tree was felled, of which the panel was made, on which the Detroit Salvator Mundi version was painted (see new and well done website by Dianne Modestini).

What does this mean?

This means among other things, that Detroit is an total and utter disaster for connoisseurs: Since the Detroit museum details who said what and when on that painting, we have to draw the consequence that everybody was wrong. Not most of them. Everybody. Hundred percent. Or, to give a few illustrious names, Bernard Berenson, Federico Zeri, Wilhelm Suida and Ludwig H. Heydenreich. The painting is after 1569. And no one saw it, guessed it or knew it. Dendrochronology had to tell it.

But what consequence is there to draw from this?

First of all: The museum (who did not reveal the results of testing) has not yet drawn apparent consequences. We still see a Giampietrino attribution (which was the most frequently cited name, one of several names now proved wrong).

The second consequence would be to rethink methodology (but this is so out of date that no one would ever think of that, since New Art History has virtually erased all deeper connoisseurial knowledge as to method and practices since the 1960s).

The third consequence is therefore the one I have drawn in the beginning. Detroit is a disaster for connoisseurs. Pity, since the picture is actually quite good. Perhaps not superb, but good. And it belongs into the group with the (almost unknown) Versailles version (now in private hands) and with the Warshaw version. And probably the Zurich version plus satellite in Holkham Hall (to which we have pointed earlier). On which basis were they done? We don’t know either, but it seems that there was a Salvator Mundi bird-nest in France, in the second half of the 16th century.

ps: the Neue Zürcher Zeitung am Sonntag recently used a picture of the Detroit version to illustrate an article on the saga of the most expensive painting in the world. Does it matter? We don’t know. But it seems that connoisseurship does not matter much today.

Five Neglected Reference Pictures or: Still Fighting Confirmation Bias:

Before we (again) name our five neglected reference pictures: let’s give a warm welcome to the new addition to the swarm: from Spain – the Pontevedra Salvator Mundi, a version that is obviously (check the blessing hand and the face with its asymmetric mouth!) related to the Detroit group (although it has now, again arbitrarily in my view, been authenticated by Martin Kemp as coming from Leonardo’s workshop).

Since today (6.12.2019) the Financial Times played with the notion of Schrödinger’s cat (as for the Abu Dhabi version, which might, in the author’s opinion, be both, dead and alive, authentic and not authentic, fully autograph and not fully autograph), we’d like also to stress that connoisseurship is not merely about conflicting intuitions, as the author also suggests. It might well be that the outcome of the whole debate will be that everything will remain a matter of belief (this, in fact, I consider to be the most likely scenario), but we are not yet at that point. And connoisseurship is, or should be, about reflected comparisons in the first place, about arguments and not about mere intuitions. If we would agree now that everything will remain a matter of belief, we would allow a case be settled, without important comparisons being discussed.

And therefore I would like to remind again the five pictures that, after careful comparisons, I consider to be the most interesting and important reference pictures:

– the Louvre’s Vierge aux balances; its author is unknown and therefore called the ›Master of the Vierge aux balances‹;

– the Columbia museum’s Portrait of a Young Woman with [without] a Scorpion Chain; it had been under suspicion to be a 19th century fake (the Pedretti camp had contradicted); by Boltraffio? or by Cesare da Sesto? or by another, unknown follower?;

– a picture of Christ that Federico Zeri had attributed to Francesco Melzi (therefore I call it simply the ›Zeri Melzi‹);

– and two pictures by Cesare da Sesto (plus workshop, probably); his one Madonna and Child with the Lamb of God (with the pebbles in the foreground; see picture), and the Hermitage picture with its very good hands;

Why is Leonardo and also Raphael influenced Cesare da Sesto a particular interesting reference as regards ›our‹ central picture? Because Cesare is known to have cooperated with another painter named Cesare Bernazzano, a Milanese who was a specialist for landscape (of rather Flemish character?) and all things natural. If for example the separately lit pebbles (mentioned also in Ben Lewis’ book), appear to be a Cesare trademark (similar scattered spots of light are also to be found in other pictures), it seems that we rather have to think of Cesare Bernazzano than of Cesare da Sesto. And the comparison between the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi’s orb with its separately lit inclusions and the trademark in Cesare attributed pictures is particularly interesting.

For more details as to the comparisons check the earlier series of Salvator Mundi related mini essays, because, for the moment, I am closing this window to the fascinating world of Salvator Mundi studies, frenzies, manias and other landscapes, because I am busy in the world of Modernism and also in the world of Asian Art. The five series of essays I have collected now as A Salvator Mundi Encyclopedia.

(6.12.2019)

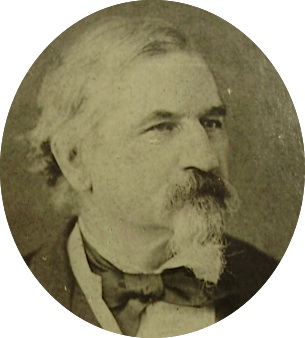

Gribble:

Gribble, the buyer of the Luini Salvator Mundi in 1900 (see OUP monograph Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon 2019, p. 27 and 298), could also be George James Gribble (1846-1927), nephew of Sir Francis Cook, in whose collection the Luini ended up. George James Gribble might not have been in art business, but still he was a member of the Walpole society (and certainly also knew Herbert Cook).

The L-Word (no, the double, triple L, again: the Legendary Lost Lunette)

We know of the vanishing point in Leonardo’s painting of the Last Supper in Santa Maria delle Grazie and of many other details concerning this rather overrestored (and perhaps also overresearched) work of art. But how can it be that just another depiction of Christ, once also to be found in that very cloister/church complex, is the blind spot of Leonardo research, and this now for more than 200 years? Because there is hardly any doubt, that Leonardo depicted Christ a second time in Santa Maria delle Grazie (the sources agree on that). But was it a Salvator Mundi or was it a Christ within the iconography of a pietà? Here comes, surprisingly, the very first attempt at all, to really clarify things that have been brushed under the carpet for all too long. And we can anticipate: full clarification does not yet seem possible.

Lunetta del portale (picture: Giovanni Dall’Orto)

»Dipinse anco quella meza luna, qual è sopra la porta maggiore della chiesa, l’imagine santissima miraculosa della Beata Vergine, un Cristo in forma di pietà, qual era sopra l’antica porta che entrava dalla chiesa al claustro a lei vicino, che poi, aggrandendola, fu inavadutamente demolito sino l’anno 1603, non avertendo fosse così insigne pittura.« (Fra Girolamo Gattico, Descrizione succinta…, ed. Elisabetta Erminia Bellagente, Milano 2004, p. 104, line 36ff.)

We have two sources that inform us as to what Leonardo da Vinci painted for Santa Maria delle Grazie of Milan. The above quotation is from the ›Memorie‹ of Padre Gattico (1574-1646) that have been edited by the Ente Raccolta Vinciana in 2004.

Still unedited is the chronicle by Padre Monti, which is a later source which, however, was paraphrased by Malaguzzi Valeri in his four-volume study on the court of Ludovico il Moro. Drawing rather, as it appears, from Malaguzzi Valeri (than from Padre Monti) Pietro C. Marani had included a Salvator Mundi that Leonardo had painted into a lunette above a door between church and cloister of Santa Maria delle Grazie into his Leonardo da Vinci oeuvre catalogue. And since Marani, apparently, not mentioned his source, the link to Malaguzzi Valeri, Monti and also Gattico got lost. And confusion reigns as to the importance of the two chronicles (Malaguzzi Valeri knew both of them, also comparing them), and the reliability of both, and finally: as to the idea of Leonardo having provided a Salvator Mundi for Santa Maria delle Grazie at all.

Why is it important to address this mess, and, as far this is possible, clarify things?

First of all: the much debated frontal pose of the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi (as well as the same pose in all other versions) might actually inspire the thought that the design was conceived for a specific architectural setting. A lunette abouve a door, for example. And the sources seem to speak of such a work. Proponents of an autograph easel painting (with the exception of Luke Syson) don’t like the idea and do not discuss it, because it might interfere with the idea that Leonardo actually did execute an easel painting. What if he provided a design for a lunette, and everything else was only derived of that concept and executed by somebody else? – The idea of an Salvator Mundi by the hand of Leonardo might vanish, as the lunette above the door did in 1603.

To give Luke Syson credit here we’d like to stress that he did mention Padre Monti (as speaking of a ›Redentore‹) in a note to the 2011 Salvator Mundi entry for the National Gallery’s Leonardo exhibition catalogue. But the discussion in years past has not focussed on the lost lunette (of which I have spoken so often in recent years that I prefer the L-word abbreviation; it symbolizes also the difficulty to bring something back to mind that has been ignored for so long and by so many). Matthew Landrus, who attributes the Salvator to Luini (with some parts by Leonardo’s hand), is another example of a scholar who mentions the lunette and seems to perceive it as a fact that a Salvator Mundi had been painted by Leonardo for Santa Maria delle Grazie.

But what is there to say now as to possible revisions, after Bambach 2019 as well as Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon 2019 have come out?

It might be as Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon have it (p. 329, note 136): that Padre Monti (which the authors do not name) might depend on Gattico, and that what Monti says (whatever he says exactly, since we are not told) is irrelevant, because Gattico, the much earlier source, speaks of a Pietà.

As we have seen above, Gattico mentions the (dead) Christ of the Pietà, and even if Leonardo did not paint a Salvator Mundi, it is still intriguing that he provided at least two iconographic variations of Christ for Santa Maria delle Grazie. And what if a Salvator Mundi was also conceived, but not executed? This is speculation, but might explain the very traditional frontal pose.

Little satisfying, however, is it (as Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon 2019 do) to just refer to Bambach 2019 in a note and, as mentioned, only to suggest that Monti might derive from Gattico (I am writing this without having Bambach 2019 at my disposal: perhaps she has indeed checked also Monti, but why then speaking only of seeming impressions). Because Malaguzzi Valeri had generally appreciated also Monti, the librarian, particualarly for his research on other matters (another lunette, for example, the other one, the first one mentioned above in the Italian quotation), thus for informations that are not to be found in Gattico. And while it might be that the Salvator in a lunette of Santa Maria delle Grazie was just a myth, a legend, product of a misunderstanding (either because Monti actually did provide an unreliable information, or because the Malaguzzi Valeri paraphrase created a false tradition) – one has to check the exact wording in Monti (the source is in the Milan state archive). Because if it is, one has to clearly say also that Pietro Marani had included a myth into his oeuvre catalogue (created, as we might say, seemingly but not actually out of nothing, since Marani did not told us his source).

And the idea of a concept for a lunette might still be debated as one possible origin of the Leonardesque Salvator Mundi design with its un-Leonardesque frontal pose, which was appropriated by that many artists that we are used to think of them as a ›swarm‹.

Brief: There was the Last Supper Christ, there was the Pietà with a dead Christ: what if Leonardo also had thought about realizing a third Christ as a Salvator Mundi then and as a possible alternative for the Pietà?

(5.12.2019)

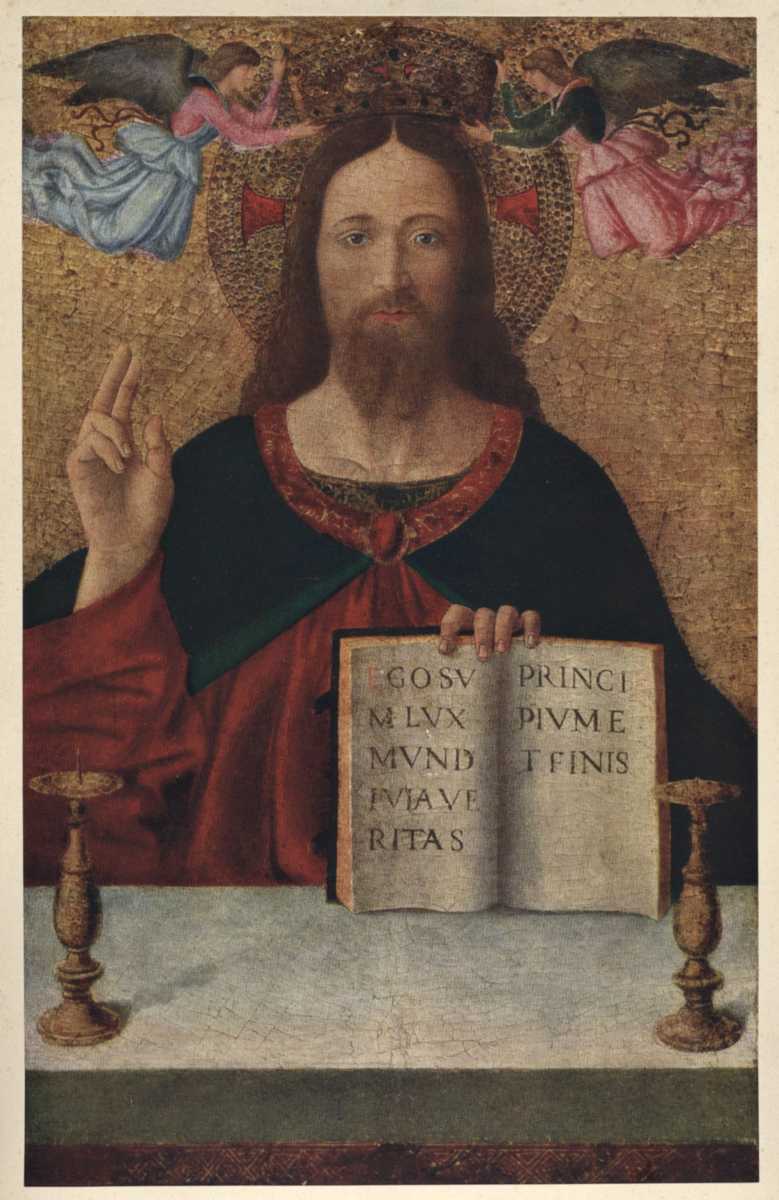

Lux Mundi:

We know of the Melozzo da Forlì Salvator Mundi which is usually presented to us as a reference for a Salvator Mundi picture by Leonardo da Vinci. But there is also an interesting picture of a Christ which has been attributed by Federico Zeri to a follower of Melozzo (picture: fondazionezeri.unibo.it). Perhaps, given this is true, the picture is therefore more or less contemporary regarding our picture in question (the Abu Dhabi Salvator).

What is interesting about this Follower of Melozzo da Forlì Christ is that, while it is formally very similar to a Salvator Mundi (just replace the book with an orb), it names the other attributes of Christ. In a book. Ego sum lux mundi. Via veritas. And: Principium et finis. And all three are interesting (for principium et finis see below).

What interests us here is the light. Christ as the light of the world (John 8,12). And the notorious sfumato. The twilight, the haze, the atmosphere, the chiaroscuro.

The question that interests me is: wouldn’t it have interfered with a c. 1500 understanding of Christ to have depicted him in a sfumato twilight? Since the Abu Dhabi Salvator is often compared with the Louvre St. John, a picture that shows a sudden encounter – with a transmitter between the secular and the holy sphere – in a smoky twilight.

But is there a sfumato in the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi at all? And would it have made sense iconographically?

In my opinion there is no sfumato. Not of the Mona Lisa type (a hazy athosphere), nor of the St. John type (the mysterious foggy or smoky twilight that has a Dartmoor/The Hound of the Baskervilles quality). Christ, even as represented as a Saviour of the World, is still the light of the world, and to depict him in a mysterious twilight would have, in a c. 1500 understanding, undermined this message.

It is true that a Giampietrino attributed picture shows Christ in a mysterious twilight (with the sign of the trinity), but our picture is a Salvator Mundi picture, its devotional message, its probably consolating function. Yes, Christ is the Saviour of the world, but this is consistently linked with Christ being the light of the world. Various aspects may show in a picture. But in a Christian environment other aspects do not simply disappear if not being represented. Ego sum lux mundi. This, as the essential message of the picture, is equally true for a representation of Christ as a Salvator Mundi. For this light and darkness is essential. Twilight is not. Because this would have transmitted the message that Christ was struggling to light the world. Even if Leonardo would have been a decided heretic (which he was not), he would not have represented Christ in a twilight. It would just not have made any sense.

NG 6161

The collection of Joseph Hirst – our present loose end of the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi-provenance (see also below under Wimbledon) – shows a mix of (old) Italian, (contemporary) British, (old) Spanish and Netherlandish pictures. Here is one, more or less prominent picture, that might have been (my hypothesis) part of Hirst’s estate: today it is National Gallery, number 6161 (or NG6161): Follower of Marten de Vos, Girl with a Cherry Basket).

Oddities, (Some New Salvator Mundi Oddities):

Contrary to what many people (especially journalists) seem to believe, the computer scientists of University of California have not solved any Salvator Mundi mystery. Simply because they three scholars based their 3D-simulation of the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi on the restored version. What they (and following them, journalists everywhere) seem to interpret as Leonardo’s work: a single distortedly rendered fold of Christ’s garment is not to be found in the cleaned state/pre-treatment photographies of the picture (and here Martin Kemp is right: there is no distortion in the picture; see Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon, p. 109). Hence there was also no basis to restore the picture, as if there once had been one. The restoration is a interpretation of the picture, probably based on other versions’ more convincing orbs – that are indeed affecting the visibility of the garment –, and probably especially based on the Hollar etching (to make it fit the etching).

But if no mystery was solved, the work of the three Californian scholars has still – if indirectly – raised important questions: why did the restorer feel entitled to restore the orb, as if there had been distortion (and why the late, i.e. post-2011 restorations have not yet documented and explained to the public)? And if the orb area shows no sign of optical knowledge displayed at all – is this not rather another disconfirming clue as to an attribution of the picture to Leonardo?

The gladness of many commentators who seem happy that Leonardo still seemingly got it right, is elusive. The Master of the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi did not get it right, nor did the computer scientists or the journalists perpetuating a silly and shallow Leonardo cult (thank God, there was modernism!).

(this addition made: 10.1.2020)

ps: the IRR photo published by the restorer shows no refraction either, while the IRR photo published in the Christie’s sale catalogue of 2017 shows the above mentioned modifications made by the restorer, which are not to be confused with structures underneath extant paint layers, made visible by IRR. Since this latter photo shows also the newly (and falsly) painted thumb by Modestini one can assume that in the Christie’s IRR all structures on that level (which means, newly added on top of extant paint layers) can be seen.

Open Questions (A new list of):

– Did Father (Joseph) Hirst of Ratcliffe College bring the Salvator Mundi from Italy, or was bought in England by his father Joseph Hirst of Leeds, or inherited by the latter Hirst’s wife (Anna Maria?), or was it brought from Ireland by the couple’s son-in-law Edward McSheehy?

– When will conflicting interpretations among proponents of a Salvator Mundi attribution to Leonardo da Vinci (as a wholly autograph picture) be adressed and discussed (conflicting interpretations as to the interpretation of the thumb pentimento, as to the authenticity of the face, but also as to the quality of lapislazuli)?

– Will proponents of a wholly autograph attribution declare how they handled the problem of confirmation bias, or will it be up to the critics of such an attribution to detect confirmation bias (everywhere in the proponents’ case)?

– How many times has the Salvator Mundi been compared to pictures by Leonardo da Vinci, and how many times to pictures by Leonardo’s pupils and followers?

– Wouldn’t it be better to distinguish more sharply between restoration in terms of integration and restoration in terms of (re-)interpretation (of a ruin)?

– And: as far as restoration in terms of interpretation is concerned: wouldn’t it be better to restore just digitally, because any consensus among scholars might be called into question any time, while an experimental restoration could not easily be taken back?

– Would’t it be better to hand the problem of the Salvator Mundi’s attribution to the next generation of scholars, since the matter cannot be freely discussed under the present circumstances (any concession of errors would be too damaging)?

– And: wouldn’t the next generation of scholars be well advised to handle this question just hypothetically (withough moving on all-too-fast from hypothesis to certainty)?

– Given our apocalyptic age: is the whole Salvator Mundi saga an expression of our age’s ultimate decadence rather than it is an expression of our age as such?

(30.11.2019)

And here my ›old list‹ of questions (not that many have been answered in the mean time, that is: since winter of 2017/18):

– Why does the Christ of the painting show beardless, if it is supposed to be the model for the Hollar etching (some seem to assume that the paint layers of the face are intact, and some don’t)?

– Is exclusive optical knowledge absent or present in the painting?

– Is the lapis lazuli used for the robe of »extraordinarily fine quality« (Nica Rieppi, as quoted by Time) or »rather coarse and contains particles of quartz« (restorer Dianne Dwyer Modestini; online brochure as provided by Christie’s, p. 71; and Modestini goes on to say: »I have wondered whether it was made by merely crushing the mineral rather than being the product of the elaborate process of extraction used in Tuscany.«)?

- Are the pentimenti to be interpreted as more than mere corrections or as mere corrections?

– Can it be excluded that the picture mentioned in the inventories of English Royal collections is the painting of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts?

– Why is the ›omega-shape‹ in the drapery, to be found in the preparatory sketches, lacking in the New York painting, while it does show in other versions, supposedly derived from or later as the New York version?

– How do the experts who do not mention the Vincenzo Monti testimony interpret it?

Original Painting (The Notion of):

›We have to change the notion of an original painting‹: this was the title (here translated from the German) that the Deutschlandfunk put on an interview with Frank Zöllner this summer (of 2019). In the interview Zöllner actually said:

»Offensichtlich war es so, dass Leonardo relativ viel entworfen hat und andere es zum Teil oder ganz ausgeführt haben.« (›Apparantly it was that Leonardo conceived relatively much and others partly or wholly did execute it.‹)

But, excuse me, this is hardly a new thought. While the title of the interview reminds me of politicians demanding new legislation, while one has to remind them that the existing legislation actually already serves all purposes and would be enough (if implemented), Zöllner sounds a bit more modest in the interview. And one has to remind that Zöllner’s own oeuvre catalogue (popularized by the popular book which it is part of) focusses more or less on the small segment of paintings that have a chance to be seen as (more or less) autograph.

And therefore I would like to remind that there is also a history of Leonardo da Vinci oeuvre catalogues: in 1967 Angela Ottino Della Chiesa provided us with a rich an excellently documented catalogue that comprises no less than 125 numbers (of which numbers 38 to 125 are works that in one or the other way ›only‹ go back to Leonardo.

How about new catalogues that, notwithstanding Zöllner’s solid catalogue, would start from there and also would reflect about the actual work of creating categories. Leonardo had a conceptual side. If one ignores it, he might appear as a dreamer who got nothing done. If one is able to see it, he suddenly appears as somebody who was quite good in delegating things and running a ›factory‹. The truth might be somewhere between this extremes, but it is hardly necessary to reinvent the notion of ›workshop‹, after connoisseurs have discussed for centuries what others might have executed based after Leonardo’s drawings.

And to say one last thing: we hardly know anything as to how Leonardo da Vinci actually handled what we today would call ›copyright‹ and ›intellectual property›. Did he allow his pupils to copy and to use his workshop materials? Did he even encourage them to do so? And the answers to these questions might not be found in documents but rather in paintings (and in respectively expanded catalogues comprising them).

Pushkiniana III. On Revisions and Revisionism

Revisions are painful. If for example I would claim that the Salvator Mundi was by the Master of the Vierge aux balances and you would prove me wrong – it’s painful. Theoretically, one might say, this has nothing personal, but scholarship has also to do with passion, and to a certain degree you identify with what you claim, and you are identified with what you claim (or have formerly claimed, because you had to – painfully – revise). I tend not to claim anyway. If I say that there are obvious relations between the Salvator Mundi and some reference pictures (like the Columbia museum’s Portrait of a Young Woman with a Scorpion Chain, my ›Scorpio lady‹ – she is bejewelled, but not wearing a Scorpion chain at all, by the way, and »revision!« I call – or the Louvre’s Vierge aux balances) I am thinking in relations and hypotheses, and I want to have these things further clarified and explained. There is no reason to move on from hypothesis to certainty all to fast. Real sceptics rarely do anyway. Hence the thinking in hypotheses can also be called a kind of scholarly life insurance. It protects you, not from errors, but from having to take back declared certainties (which, in scholarship, is the most painful and damaging thing to do). Think of the dendrochronological haircut that happened in Detroit – 200 years of scholarly thinking proved wrong, and one might imagine how painful this would have been for connoisseurs like Federico Zeri, who, however, passed away in 1998, and, perhaps luckily, never got to hear about it. The notorious 450m of the Abu Dhabi Salvator have turned into a gigantic magnifying glass, and everything we see under this glass is dramatically magnified, although revisions are the daily bread of the scholar. Magnified are the good and the bad, the damage and the glory, and we should be willing to do our best to turn all into something good. And if, under this magnifying glass, we would also discuss ethical standards – this would not be the worst thing to do – I imagine.

I am quoted in Ben Lewis’ book for ›Expertise precedes scholarship‹. This was pointed to Ludwig H. Heydenreich, whose 1964 article in the Raccolta Vinciana is seen as the beginning of modern Salvator Mundi scholarship. Because Heydenreich had authenticated a Salvator version after the Second World War, and only then begun to research the whole field of other versions. After 1964 he authenticated the same version again, and seen in hindsight, this was no big revision at all, but seen from today, both expertises are probably dead wrong (I am not going into detail here), and the big revision was only to come.

The most dramatic revision we have seen so far in the case of the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi (among Salvator Mundi conoscenti it is also known simply as ›Cook‹) is perhaps the comeback of the Pushkin Museum’s Salvator Mundi which shows a young Christ, but is definitively to be placed into the collection of English king Charles I. While the Abu Dhabi Salvator might also have been in that collection, but presently is only placed there hypothetically. This is not about the question who saw the Charles I stamp on the reverse of the Pushkin Museum’s picture first or who knew about the provenance first – the museum did and was anyway – and I also concede that others might have known before me. But I am writing this not least because in 2016 and 2017 I have published about that picture, and I have been and still am affected by another type of revision: I see myself partly or wholly eliminated from that story as being the one who raised questions first publicly. In 2017, after the Christie’s auction, it was not exactly an opportunistic thing to do to put a list of ›open questions‹ concerning the Abu Dhabi picture online – others went on the »party« in the meantime. What I said there is quoted in the US-edition of Ben Lewis’ book in a note on page 114. And I claim – here I am claiming – that I was the first to raise the question publicly – since nobody had mentioned the Pushkin picture in 2011 or afterwards in the context of the debate on the Abu Dhabi Salvator – if there possibly could be a problem with the all-too-ready identification of the Salvator Mundi mentioned in English Royal inventories with the Abu Dhabi Salvator. Put in simple words I tended to think that the provenance was ›overbooked‹ like a twice sold plane seat. Airlines do that or did that, because they cannot be sure if passengers turn up. But here a passenger did, rather late, but he did. We have two seats for a Christ, but so far only one of them is for a Christ as Salvator Mundi. And there are other possible candidats for the other seat. I don’t want to do fingerpointing here, I am just reminding how I see things. And I expect to be acknowledged for what I did, be it in journalistic articles and books or in scholarly books. And in case the Vierge aux balances in the Louvre will be seen in relation to the Abu Dhabi picture once in the future (and for the reasons I have given), or the Columbia ›Scorpio lady‹, just for the record, here is also a reminder that I did publicly first raise these questions – for very specific reasons –, too. (Dietrich Seybold, 19.11.2019)

On the left the Leonardeschi cabinet from our virtual Louvre show: two loans (the Columbia museum’s ›Scorpio lady‹ and the Salvator Mundi), appropriatedly grouped with the Louvre’s own Vierge aux balances.

On the right the autograph stars from Leonardo’s late work. (This grouping does not reflect any certainties – I would not be claiming that –, but a working towards such certainties that takes into account the problem of confirmation bias; for our reasons see my Salvator Mundi Microstories and particularly my Salvator Mundi Afterhoughts).

Upcoming Revisions (possibly upcoming):

I have two suggestions to make:

1) Since we have little reflection on what the notion of ›workshop‹ actually does mean in the case of Leonardo (the notions of ›workshop‹, ›circle‹, ›follower‹ are very cloudy), but since we also have – with the Pala Grifi – a ›window‹ into the world of his ›circle‹ (this was a pre-1500 commission Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono worked on as a team, and it was their own commission) one should use the model of the Pala Grifi to think about various models of how the relation of Leonardo and his followers can be thought. Because the assistants were, obviously, also freelancers, while being attached to Leonardo. And one should also think about what that might mean regarding the Salvator Mundi.

2) Only recently scholarship has begun to discuss the phenomenon of so-called ›belated Leonardism‹. This might be defined as: ›the second generation of followers that begun to study Leonardo again more closely, after the first generation had also tended to move away from him‹. And we have also to think about what that might mean regarding the production of Salvator Mundi pictures. What about Gerolamo Figino, for example? Who is now thought to have worked with (or have been influenced by) Francesco Melzi. And Melzi had been still young, when Leonardo had died in 1519, and had not only inherited his master’s manuscripts, but also his workshop materials. And although new Melzi scholarship has been conducted in recent years (by Rossana Sacchi), we still seem to know rather little, what this pupil of Leonardo actually might have done with these materials.

Wimbledon (A Mayor of):

I think that to the gallery of former Salvator Mundi owners we can also add now Edward and Theresa McSheehy of Wimbledon. Theresa, born Hirst, was the only daughter of a Joseph Hirst of Leeds, and she had married Edward, an Irish army surgeon who later was to become mayor of Wimbledon. I think that, while Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon suggest that there were no heirs to Joseph Hirst (because father Hirst, the Joseph Hirst of Ratcliffe College, his only son, had passed away before him), Theresa had been the actual reason that Joseph Hirst of Bramley/Leeds had moved to Wimbledon. This genealogy (that implies that Theresa was the sister of Father Hirst of Ratcliffe) is also confirmed by at least one genealogical website, but British scholars might be in a better position to check it (all you have to do is to get you a decent family tree of a former mayor of Wimbledon; Wellcome Library of London has McSheehy materials and might also know about living relatives).

Tentatively I say that the provenance goes: Joseph Hirst of Bramley/Leeds and later Wimbledon; Estate of Joseph Hirst (Theresa and Edward McSheehy, Wimbledon), sold at Christie’s in 1900; Sir Francis Cook (via Gribble and possibly Robinson)… This is also what we presently have to call the loose end of the Salvator Mundi provenance.

See also: A Salvator Mundi Provenance

Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

Some Salvator Mundi Afterthoughts

Some Salvator Mundi Variations

Leonardeschi Gold Rush

A Salvator Mundi Geography

A Salvator Mundi Atlas

Index of Leonardiana

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Some Salvator Mundi Revisions  |

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS