M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Iconography of Connoisseurship

Iconography of Connoisseurship

What we are proposing here is not a brief history of connoisseurship in six visual examples. It is a reflection about topical structures within that history. And we make a start for our envisioned Visual History of Connoisseurship by choosing six pictures (and a couple of links), that seem to embody essential things and do inspire brief reflections or comments of mine and hopefully of others…

One) Portrait of Carl Friedrich von Rumohr by Friedrich Carl Gröger

One) Ideally or idealistically real knowledge of something grows out of a deep love or passion for something. That’s why we find that our first example should be an expression of delight, of joy. We find this expression in this picture of young Carl Friedrich von Rumohr, who obviously is drawn to something outside the picture’s frame and fascinated by that something he is just observing. It might be a view of nature, it might be another’s students work, it might be his own work he has just started or finished. It might be the effect of something that is not finished, but in any case: that causes this particular glimpse of delight, which, we find, the painter Friedrich Carl Gröger, at about 1802, did render magnificently and with sublety. It’s this lightening of expression that makes one think of inner delight – and we realized that here is a passion that already has grown out of a love for something, but it is still about to grow, and it will be growing further.

Compare:

It will be disappointed as well, because we know that Rumohr became more of an art historian and connoisseur and less a painter and draftsman, and it’s just the scientist that may question our ideal definition of connoisseurship above. But let us ask back: Is it not the passion for something that a teacher of that something is meant to propagate? And is it not crucial for every scholar to maintain that passion for something, even if an idealistic definition of science might be that it is about a knowledge, which is not tainted by anything subjective, i.e. love or passion for this something?

Two) Un coin du Salon en 1880 by Édouard Joseph Dantan

Two) It is about the picture on the left – and it is not. We spoke of inner delight, and we also may find it at art fairs and – if we are citizens of the 19th century – at the Salon, even if cacophony ceaselessly surrounds us. We find much in that picture on the left that delights us, and it is an especially beautiful rendering of children at a (temporary) museum and of the order of things that is a bit at risk. And its title refers not to the art world as such, but to a corner. We don’t know if we find connoisseurs here, but we are inspired to ask: Is it a social activity, if connoisseurship is thought as an activity? Or is it rather to be found here. Yes, we only give the link, and you have to go there and find out for yourselves: Why is the title of this Daumier picture The Connoisseur; and why is there an alternative title, namely L’Amateur. And do we see there, at the virtual Met, the worldly version of a hermit? Or is this man by no means thought to be alone? And what does it mean at all: alone? At any rate: If the connoisseur is thought as a collector, from time to time he or she has to go there where he or she finds what he or she appreciates. And if connoisseurship would be thought, for once, as a landscape panorama – there is the noisy city with its hopefully quiet corners, and there is the real landscape (with its caves) that only can be thought in opposing relation to the noisy, but also challengingly inspiring city.

Three) Still from Martin Scorsese’s 1993 movie The Age of Innocence; DoP: Michael Ballhaus (picture: allexperts.com)

Three) No, it’s not me, it’s Daniel Day-Lewis, who is playing Newland Archer in this fine movie by Martin Scorsese. And this very scene brought him to the cabinet of Countess Olenska, where he does, while waiting for her to show up, look at her pictures. Odd pictures, as like, I imagine, he has – although an avid visitor of art exhibitions in London or Paris – never seen before. And isn’t this still also making a point for the, we think, founded theory of art looking back at us?

Maybe Newland Archer is wondering here, who did paint this odd painting that is looking back at him. At least other viewers of the movie have become curious, what they were looking at (and this is why I did find this rare still posted on AllExperts.com, and also some answers provided by the experts). Thus what Archer does experience, the viewer might experience as well. But we may, maybe also like Archer, also reach the point of asking: Is this the embodiment of connoisseurship – to merely ask (or play the game of) who did paint what?

It’s a still and maybe you have noticed that Archer might actually already be sneaking into the other room that shows on the very right of the frame, while passing by this long and odd picture. And he does not comment upon it – but until the very end of this fine movie. When, we relate it to the still, he says to his son, whom he has accompanied to Paris, where Madame Olenska, the love of his life he has missed, now lives (he does not got up to visit her, but sends his son), and maybe it’s his son who relates to Madame Olenska what Newland Archer says, and what comments upon the painting we see in the still, because all he has to say to his son on Countess Olenska, and it takes him quite an effort to say something at all, is that »she was different«.

And we may conclude by saying: yes, it is about the culture of attribution. Connoisseurship, in its narrowest sense, might mean to situate the »different«, the unlabelled, to attribute it to its author. But what goes on around that »game« of who did paint what, is more. It is about the art looking back at us. It is about the opportunities in life and the missed opportunities and maybe, like here, the bittersweet, or rather bitter memories of it. And some connoisseurs did leave the track of merely playing the before-mentioned game (check out the section on forgotten connoisseurs above). To do something else. To think more about art that does look back on us. Or to move into that other room, whatever it may be hiding, that shows on the very right of this rare and beautifully lit still.

Four) Still from John McTiernan’s The Thomas Crown Affair (1999)

(picture: rottentomatoes.com)

Four) Here is nothing quite what it would seem, and much or everything about appearance and illusion. First of all: Is this the Met? Well, no, it isn’t, but just a set. But one might say that this movie is indirectly about the not exactly thin line between the Met, the people’s treasury, and the world of the elegant and superrich, residing exclusively with their art treasures at the Upper East Side of New York (the thin line being, of course, Fifth Avenue). Almost everybody in this beautifully playful movie seems to associate art mainly with glamour, luxury and money (again a nice scene, by the way, with children in a museum), and even the museum’s guard: ›I just like my haystacks, Bobby‹, the elegant man sitting here says to the museum’s guard, who points to other famous paintings at this fake Met. But still, connoisseurship is not necessarily about luxury and money, and the one who at least seems to know this, is the elegant man sitting here (even if he uses the display of a real deep passion only as a mask to hide his plan to elegantly steal from the people’s treasury and to duel with the detectives of the police and the insurance company involved). But this movie is not about an (fake) art theft in the first place, but more about watching elegant people play with and dupe each other. The motif of forgery comes in, and the humiliating demasking of a forgery (humiliating for the female art detective working for the art insurance company). But in other ways the movie is about topics of connoisseurship, too. The Trojan horse, for one, that carries a load of rogues into the fake museum is declared as an first century Greco Asian horse to the museum. In truth (or on some other level of reality) it is a prop designed after Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings for the Sforza-monument (at least the audio commentary of the DVD says so) and smuggled into that movie. And about connoisseurship, understood as insight into human nature, it is in the very end. Because a forgery is shown to an already imprisoned forger, who, when looking at the painting, displays a glimpse of joy, which, later and in retrospect, is interpreted as paternal pride and leads to the identification of the actual forgeress.

Five) (Picture: deviantart.net)

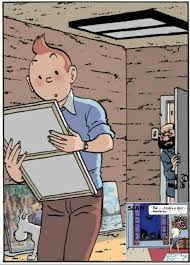

Five) As we know Belgian cartoon artist Hergé left a Tintin album unfinished, which is entitled Tintin and Alph-Art, and is about art forgery and also about modern art. And the question is not only: what had Hergé to say on art and art forgery, how did he reflect upon actual cases of art forgery that echo in the story, but also: how much Hergé is actually in that picture that we show? Because we face the workshop problem here and not least: the problem of pastiche (and both are classical problems within many areas of connoisseurship). But in any case: what we see here looks very much like the quintessential duel between art detective (or connoisseur) and some representative of the dark side, which might be found out, but as we also know, Tintin, according to the story, faced the risk of being killed and his dead body being encapsulated in a sculpture that was meant to bear a forged signature emulating that of real French artist César.

It may be that in more than one sense Tintin, the reporter, left his life investigating a case of art forgery, be it that he died with the Alph-Art-album, be it that he died within the story. And those who prevent him from dying are actually those who make him live by producing finished versions, pirate versions of the Alpha-Art-story or further Tintin-pastiches. And we see that ethical questions, ethical conscience is as crucial as to connoisseurship as is the detective spirit and the judgment by eye.

Six)

Six) One of the many remarkable things about the BBC1’s Fake or Fortune? programme is that it has made the authentication process a public affair. Which is not completely new, because journalists have been involved in many and also famous authentication issues since the »Holbeinstreit« of 1871 (and occasionally it’s only the investigative journalist at all that forces the differing opinions in something like a debate – in calling them, emailing them or visiting them more or less unexpectedly). But here whoever is involved in making a case for or against a particular attribution of a picture is expected to justify himself or herself – in public and to the public. And even if the representatives of the programmes, at a certain point, do not insist further in questioning authority, – the media itself does, and one of the interesting things will be to observe if this has consequences in terms how the various players and also institutions involved in authentication issues will in the future define or redefine their role.

The metaphors, in the meantime, have become bloodier. »Paint acts like blood on a crime scene«, says art dealer and art detective Philip Mould, one of the three presenters of the programme, during the opening titles of the first series. For Giovanni Morelli in 1878 a painting was just a suspect, to be looked at with the eyes of an »ex police commissioner« and to be questioned (if it, possibly, showed, in its self-declaration, a fake passport to the police commissioner). And we close the first series of our programme here by referring to the nice portrait of Alan Burroughs by Molly Luce (see here) that Evan Hepler-Smith showed during his presentation on Burroughs and his working with X-rays (see also here) at the 2014 The Hague conference on authentication in art. We take X-rays just as the symbol for what Philip Mould also says during the opening titles of Fake or Fortune?: »In the past we looked at pictures, now almost you can look through them.«

Back to the starting page of Dietrich Seybold’s homepage: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/HomePage

© DS