M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

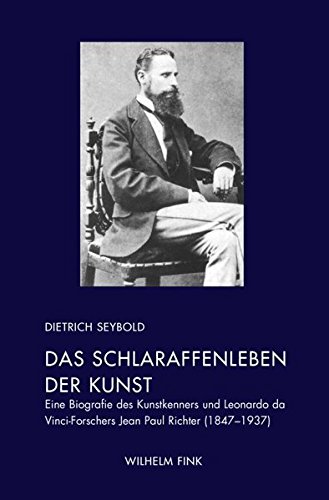

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

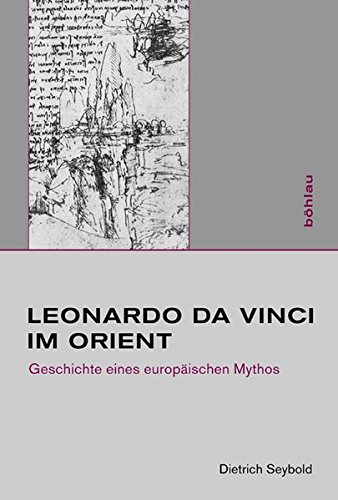

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

SPECIAL EDITION

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM A Salvator Mundi Puzzle |

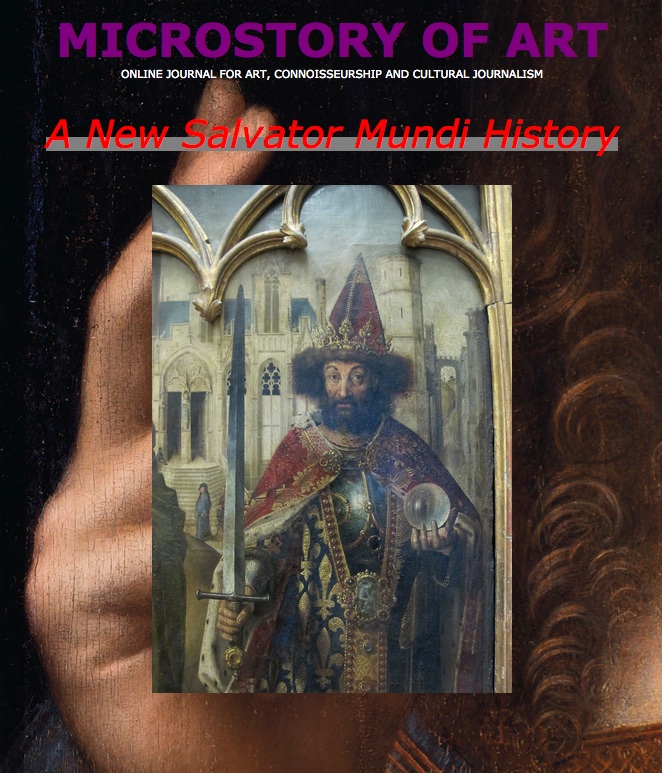

(4.5.2021) This is meant to present a couple of new Salvator Mundi related finds and reflections. I am proposing a bundle of new hypotheses pointing towards a New Salvator Mundi History. What would be new? I am proposing a new attribution for the Cook version (which still I am regarding as a key picture, and I am also going to say why), and I am proposing basic thoughts for a history of all the Salvator Mundi versions, in which the history of the one key picture would be embedded. Please note that I am speaking of hypotheses. It is my credo to say: I am thinking in hypotheses – what can be regarded as the truth remains to be seen. Since I actually have no wish to engage in polemics, I am glad being able to say that I am also proposing a number of ›third ways‹ in Salvator Mundi thinking.

A Salvator Mundi Puzzle or: A ›Last Leonardo‹ in Some Sense?

It may come as a surprise that I am going to begin with speaking about Raphael. And Leonardo.

What was Raphael actually doing when, in 1516/17, Leonardo da Vinci left Rome for France? We do know for example that Raphael had to rework the Coronation of Charlemagne (left/right) after February 1516 (see Robert Williams 2017, p. 221, note 258), due to »recent political developments«, since pope Leo X had negotiated an »accord with King Francis I« who was, if we return from politics to the artistic scene, going to be Leonardo’s new patron. The Coronation of Charlemagne depicts Francis I, Leonardo’s new patron as Charlemagne. And it depicts him holding a globe.

When Leonardo da Vinci said good bye to Raphael, he said good bye to him for the very last time. We can assume that they said good bye, even if we do not know that for sure (for example because Raphael was so busy). In the summer of 1516 Leonardo was in Rome, and this we know for sure. And this is what Raphael – with his workshop – was doing when Leonardo left Rome for France: depicting French king Francis I as Charlemagne holding a globe; and I am also assuming that Leonardo – who had lived in the Vatican – knew this design. Which means: we can be relatively sure that Leonardo was aware how his future patron could be seen, how he was seen in art or propaganda, and that the question of how artists could or should represent the king, was a question commonly debated among artists. It is about the history of mentalities here also, as much it is about the history of actual political iconography. In which Charlemagne was usually depicted holding a globus cruciger. Here, in 1516 and in the Vatican, Raphael depicted him (and had him depicted by his workshop) holding a globe.

Twice (?) a Rock Crystal Orb – Replacing a Globus Cruciger

And there is another painting depicting Charlemagne not holding a globus cruciger. It is a picture now in the Louvre, and a picture that was of enormous importance – for its political iconography. It is the Crucifixion of the Parlement of Paris, painted in about the time Leonardo da Vinci was born, which means ›around 1452‹, and it has Charlemagne holding an orb. And orb, as an Louvre issued booklet by Philippe Lorentz (apparently) has it (since due to the pandemic it is too difficult at the moment to check it in the library), an orb made of rock crystal. This is the, perhaps the only, or: perhaps the first rock crystal orb in painting. The next, the other, or just another (as we do not know this for sure) may be the Salvator Mundi version Cook (if we accept for a moment that the orb represented in it is made of rock crystal).

Why was this Crucifixion of such importance for its (political) iconography? Because it was painted for the Parlement, the High Court, and showed the ideal kings (Saint Louis and Charlemagne), thus showing – to any French king up to the Revolution – the ideals any king, and also Francis I, had to live up to. In other words: for any artist, and particularly for artists close to the king (as the Clouet brothers, Jean and Polet Clouet), this was a reference picture of enormous importance, placed ar the heart of French politics. And one might add that the artist(s) who had painted it was or were probably Franco-Flemish artists as the Clouet brothers, who were of Netherlandish descent.

One has to see Francis I among his courtiers, diplomats, painters, humanists, and Leonardo da Vinci, moving to Cloux (Clos-Lucé), close to Amboise (where the royal family lived) was becoming part of this environment. Thus one might say that he moved into a scene, into an atmosphere, in which it was common to compare Francis I with Charlemagne (as Raphael had just done), or to idealize him as Charlemagne. And artists thinking about representing the king (as Jean Clouet, with his brother, was to do) certainly knew this reference picture at the Parlement of Paris.

Any reader familiar with the Salvator Mundi controversy may now sense at what I am getting at. There is the question if, since we find (just about) two pictures in the history of painting which show us a rock crystal orb, and this at a place where one would traditionally expect to see a globus cruciger, there is the question if there is a link between these two pictures, or is this just coincidence?

One might think about a link on the level of material objects (was or is there such an object in the royal collections), and I do not know of such a link. On such a level the link is possible, but it would remain a purely hypothetical link, unless such an object would be found.

On a level of (political) iconography it is a little different. We do not know for whom the Salvator Mundi version Cook was painted, but we have all kind of hypotheses indeed. Was it painted for pope Leo X (see for such reflections Frank Zöllner in Leonardo a Roma, p. 260ff., referring to Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon 2019)? Or was it (perhaps begun in Rome) painted for a French king, namely for Francis I? This is not exactly what I am getting at. But I do want to propose the hypothesis here that the Salvator Mundi version Cook was painted during Leonardo’s stay in France. Close to the king, with a pupil of Leonardo basically painting (perhaps continuing, and perhaps also finishing) it, with Leonardo intervening in it and contributing to it, and this all in interaction with the Franco-Flemish artists, namely the Clouet brothers, who might have known better about the iconography of the French monarchy than Leonardo and his pupil, and certainly knew the Crucifixion at the Parlement of Paris, and might have helped Leonardo and his pupil to adapt a Salvator Mundi painting to French needs.

This said one may now ask ›who was the pupil?‹. Well, I think that this pupil was Francesco Melzi. Salaì was probably there from time to time (we know also that he was once in Paris, at the time Leonardo dictated his will), but the pupil might have been Melzi for a number of reasons. First of all there is Antonio de Beatis, the secretary of the Cardinal of Aragon, speaking of one pupil working well. And Leonardo thought high of Melzi – since everything relating to his profession as a painter he inherited to Melzi and not to Salaì, and this apart from the third reason, which might be the quality of painting seen in Salaì’s own signed and dated picture of Christ.

Thus I am proposing that the Salvator Mundi version Cook might have been ›The Last Leonardo‹ in some sense. By which I mean: It might have been one or even the last painting Leonardo actively contributed to, as far his health still allowed it (he seems to have suffered a stroke), and apart from the fact that the design that had existed earlier can be attributed to him. But I do think also (and agree with Jacques Franck here) that it is not a picture worthy of Leonardo insofar as we speak of the whole. The blessing hand, the inclusions of the orb, yes, we may see these parts as ›Leonardo’s last words as a painter‹ (in my view the original hand is anatomically correct), but I don’t think that Leonardo painted this painting in Rome (or in earlier periods), and I don’t think that he painted the whole. And this now apart from the fact that it simply makes sense to see this picture embedded in the history (of mentalities, artist’s travels, political iconography, exotic objects) laid out above. If the theory I am proposing is wrong, one question still would remain. The question if still there is a link between the two orbs, made or not made of rock crystal.

It has already been argued that a ›blue‹ Salvator Mundi, instead of a traditional ›blue-red combination‹, might be a clue that the painting was adapted to French needs. Frank Zöllner has thought about this (see Ben Lewis’ book for that), and the blue might indeed be »bleu de France«. The rock crystal orb might be a second clue. What I am thinking is not that Leonardo had ever seen the Paris Parlement orb. What I am thinking is that he might have been informed about these particular currents in political iconography as laid out above. A rock crystal orb with Charlemagne, the ideal king, holding it. It is not far fetched at all to think that this may have contributed to inspiring the Salvator Mundi orb. The ›third way‹ in Salvator Mundi thinking that I am proposing means: the Paris orb might be indeed rock crystal, but what Leonardo and his pupil created was created on the basis of what Leonardo had seen in his life, of what he knew of rock crystal, and in addition to that, it might have been simply hearsay as to the Paris painting that might also have contributed to this orb. Which is a particular refinement to the basically rather simple composition. And by ›hearsay‹ I mean: all that the Clouet brothers might have told Leonardo or Melzi about the political iconography of kings, of orbs replacing a globus cruciger (also in an image of Christ), and of a particularly exotic object as the rock crystal orb is. (And we are not even thinking about what exactly Salaì was actually doing in Paris in 1519).

And one final question, before we arrive at outlining a New Salvator Mundi History: it is the question if Leonardo actually interacted with the Clouet brothers. Traditionally one does assume that Jean Clouet learned from Leonardo himself in doing portraits. But what we do know is that the portrait of Francis I as St. John the Baptist (in the Louvre; picture on the right) was done in 1518 (thus at a time when Leonardo was there). It is so obviously inspired by Italian Renaissance painting (if not to say: by Leonardo) that art dealers, during the 19th century (as the Louvre recalls in the picture’s dossier), repeatedly sold it as ›by Leonardo‹. It is one of the many pictures that add to the large Museum of Ex-Leonardo-pictures, and only after the (long forgotten) Clouet family had been rediscovered, it had been attributed to one of the members of it (Jean Clouet).

A New Salvator Mundi History

I am still regarding the Salvator Mundi version Cook as a key painting. And laying out – in very broad strokes – a number of hypotheses that point toward a new Salvator Mundi history, one will also understand why:

We may start by simply saying that the Salvator Mundi design predates Leonardo’s stay in France.

There is a first family (as I call it) of pictures of Christ in a similar design, and the Christ by Salaì may be representative of that group. It is not necessary to go into details here. But it might still be necessary to say again that the basic design (not speaking of the refinements here) was rather simple. And similar designs can be found in other places and earlier. I have, earlier, pointed to the Giovanni del Biondo design shown here (a 14th century picture). And I am adding a beautiful Benozzo Gozzoli design here (in the Louvre), made at about the time Leonardo was 20 years old.

A first group of pictures, based on the same cartoon, may have already existed, when the Cook painting was made (as supposed above). The thumb pentimento, in my interpretation, is not a change of mind, but a correction, and other version, with the thumb in the final position might have existed before, simply because their common reference was a cartoon, and not the version Cook.

But what happened after this key painting, as I am calling it, had been created?

It is, for one, important to recall that the royal household moved from Amboise to Fontainebleau rather soon. If the version Cook was not among the Leonardo paintings Francis I acquired, there is the simple explanation that it just was not finished, but still might have ended up in the belongings of a member of the royal family (Louise of Savoy, the king’s mother?) or a courtier moving with the household. Since the design lived on – in the (second School) of Fontainebleau. I am not going into details here either, but this is the second family of Salvator Mundi paintings. Those pictures, made by Franco-Flemish artists who had adapted the design and reinterpreted it. One of these pictures Wenzel Hollar might have seen, who copied it in 1650, thinking that it was by Leonardo.

But as I said – Francesco Melzi inherited the workshop (everything relating to Leonardo’s profession as a painter). And this, in my view, is why there is also a third family of Salvator Mundi paintings. All those based on the design that returned to Italy – with Melzi (who for example, as we do know today (see Annalisa Perissa Torrini in the Festschrift for Carlo Pedretti), cooperated with a very capable artist named Girolamo Figino; a rediscovery of that artist is presently underway in Italy).

And in addition to these three families we have those pictures deriving from one of the mainstream pictures (Holkham Hall, for example, in my eyes, derives from Zurich. All together, the whole group I like to call the ›swarm‹.

This is, basically, how I would think a New Salvator Mundi history. Finally: Why do we not have any documents about the Salvator Mundi version Cook?

There might be a simple answer to that as well: Because there was never a commission needed. Leonardo (and Melzi) were being paid a generous pension. So generous that one recent Leonardo biographer (Volker Reinhardt) wondered how Leonardo might have spent all that money he got then (p. 310). Is it far fetched to think that he did spent some of it on pigments?

This, in brief, is how I would see – hypothetically – the solution of a gigantic puzzle. What I have proposed is a new attribution (compatible to everything I have written before about the Columbia portrait as a reference picture), as well as a new bundle of hypotheses. I have presented a number of new finds (the Paris orb), and of ways to to re-organize the evidence. And I have proposed two new ›third ways‹ in Salvator Mundi thinking. One relates to the genesis of the orb in the version Cook, another to seeing the picture as the ›last Leonardo‹. Which it might be – in some sense.

PS: As to the crossed stole I am thinking that both a statue in Rome as the painting version Cook relate to a common iconography of Christ as priest. As to the version Ganay (not shown here; above on the right is Detroit): it is noteworthy that a globus cruciger is part of the design and not a glassy sphere. And finally as to the orb: a recent computer simulation that meant to show that it is made of glass was based on what the restorer, Dianne Modestini, had added to the picture (refractions inside the orb). And it does not add to the question if we do know: what Modestini had painted – if it was real – would be glass. This is also a too simplistic way of thinking what representation is.

PS2: The Paris Crucifixion had been commissioned for the Parlement’s room of the king. Did Francis I ever sit there? It seems not only possible but likely. On 2 February 1517, for example, a «séance royale« was held, including a ›king’s speech‹ (see Roger Doucet, Etude sur le gouvernement de François Ier dans ses rapports avec le parlement de Paris, passim). This is as close as we can get to a warrior-king, possibly looking at a picture of Charlemagne, his chosen warrior-king role model, with Charlemagne holding an orb that obviously can be seen as a representation of rock crystal.

PS3: Louise of Savoy would have been the ideal recipient of a Salvator Mundi picture. She had wanted Leonardo in France. She (and her son) had commissioned a tapestry copy of Leonardo’s Last Supper years earlier (it ended up in the Vatican – and we come full circle). Leonardo as well as Melzi owed their generous pensions also to her. It would not be far-fetched either to think that Leonardo and Melzi may have paid her respect with a smaller religious painting. And thus the Salvator Mundi version Cook might even be seen as a distant echo of the Last Supper. We might speak of another full circle.

See also: A Salvator Mundi Provenance

Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

Some Salvator Mundi Afterthoughts

Some Salvator Mundi Variations

Leonardeschi Gold Rush

A Salvator Mundi Geography

A Salvator Mundi Atlas

Index of Leonardiana

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM A Salvator Mundi Puzzle |

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS