M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

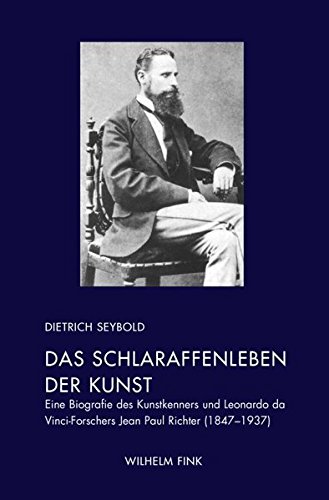

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

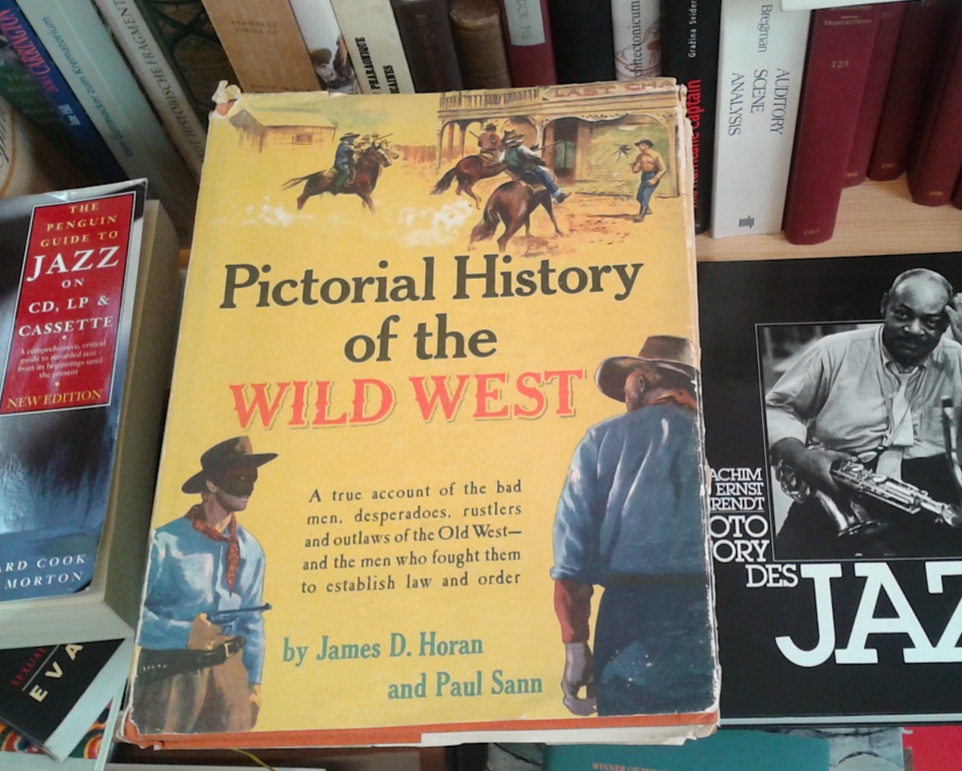

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

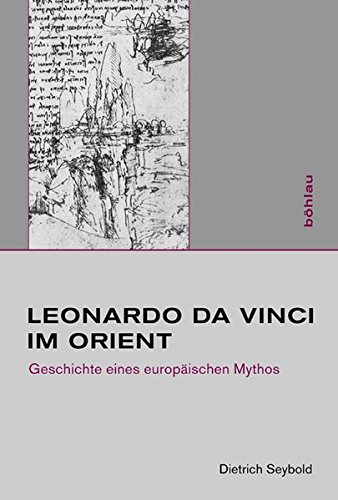

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

A new series of snippets we start here and a new project: the Visual History of Connoisseurship (ViHC), provided by the staff of the Virtual Museum of Art Expertise and organized chronologically (picture above: pinterest.com). Instead of much explanation we start right away with something certainly rather unexpected: with a 13th century anecdote, telling us something about the perceptiveness of a Sufi-connoisseur at the city of Konya (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Konya).

A 13th Century Sufi Anecdote  (Pictures: ceramicfulbright.blogspot.ch; bg picture: DS) |

»It is from the divine Name, the Creator… that there derives the inspiration to painters in bringing beauty and proper balance to their pictures. In this connection I witnessed an amazing thing in Konya in the land of the Greeks. There was a certain painter whom we proved and assisted in his art in respect of a proper artistic imagination, which he lacked. One day he painted a picture of a partridge and concealed in it an almost imperceptible fault. He then brought it to me to test my artistic acumen. He had painted it on a large board, so that its size was true to life. There was in the house a falcon which, when it saw the painting, attacked it, thinking it to be a real partridge with its plumage in full colour. Indeed all present were amazed at the beauty of the picture. The painter, having taken the others into his confidence, asked for my opinion on his work. I told him I thought the picture was perfect, but for one small defect. When he asked what it was, I told him that the length of its legs was out of proportion very slightly. Then he came and kissed my head.« (Source: Ibn Arabi (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibn_Arabi), Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya (›The Meccan Illuminations‹), II, p. 424; here given after Sufis of Andalusia, Sherborne 1988, p. 40f.)  (Pictures: ceramicfulbright.blogspot.ch) |

Commentary: With Ibn Arabi – who by the way might have visited Konya in about 1216 – painting attained the status of a »mental object«, Abdelwahab Meddeb (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdelwahab_Meddeb) is writing in the essay that also drew my attention to this anecdote (Orient und Okzident. Politiken des Bildes, Bilder der Politik – der Westen in den Augen des Islam, in: Lettre International 87, p. 44ff., quote on p. 51). And I believe this is a subtle interpretation of an anecdote that obviously reflects ancient Zeuxis anecdotes, as transmitted by Pliny and others. But it is not with a sense of playfulness that Ibn Arabi did transfigure the Zeuxis tradition into something else, into a reflection about ›spiritual guidance‹, a Sufi-mentor knowing his pupil (and the pupil testing the mentor as to this knowledge), and at the same time, of course, about seeing, painting and also appreciation of painting, and this in a context… well, in what context? Meddeb cites this to relativize the reputation of reserve (if not to say: hostility) to images, found within Islamic cultures (in various degrees, and resulting in various ›pictorial cultures‹ and ›subcultures‹), and of course one might ask now, if this anecdote is indeed about real images, or only about mental images, or in fact a mere playing with the idea of images and painting as transmitted by ancient texts. I leave it to the experts to explain with what actual imagery Ibn Arabi might have been confronted with during his travels and on his actual stays in the very Konya region. And as a mental image, meant to help to produce actual images of partridges, we give below a partridge scheme, meant to help and to inspire young painters to create images of partridges of whatever kind.  (Pictures: ceramicfulbright.blogspot.ch) |

(Pictures: digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de; kostenlose-ausmalbilder.de; bg picture: ceramicfulbright.blogspot.ch) |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM 14th Century: Ibn Battuta Travels to China or The Chinese Art Market and the Issue of Provenance  |

Ibn Battuta, the Muslim world traveller of the 14th century (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibn_Battuta), did also visit China, praised the Chinese artists as the world champions, especially in painting, and found himself, while visiting the capital and after having strolled through what he calls a ›market of painters‹, being candidly portrayed. His portrait, and also portraits of his fellow travellers, were immediately hanging on the walls, as to provide another proof of the Chinese artists’ mastery, but in truth because the ›sultan‹ had given order to do so, and this for measures of security: if needed, such portraits of foreigners could be sent out to the whole country, in case of one of these foreigners being suspicious of having committed a crime. *  |

And if we seem to encounter 14th century police methods of manhunt here, aiming to identify a wanted person with a foreign provenance by facial recognition, we do also encounter, if strolling – as a foreigner – through the history of Chinese connoisseurship, particular methods of how to document the provenance of paintings: because owners of scrolls – we take as an example Huang Gongwang: Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwelling_in_the_Fuchun_Mountains) – added, on papers added to these scrolls, inscriptions to these scrolls, providing the collector or next buyer on the one hand with provenance informations, but on the other hand providing the connoisseur of Chinese painting also with another, more advanced problem of provenance research: with the problem to tell the authentic inscription, seal, poem or commentary from the fake one. And we imagine Giovanni Morelli, the 19th century Italian connoisseur, travelling to the Chinese 14th century, and taking his inspiration here, for his occasional speaking of paintings being ›rogues‹, that were declaring a wrong identity to the police officer/connoisseur by showing a fake ›passport‹. |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM 15th Century: A Possible First Encounter With Modern Western Connoisseurship  |

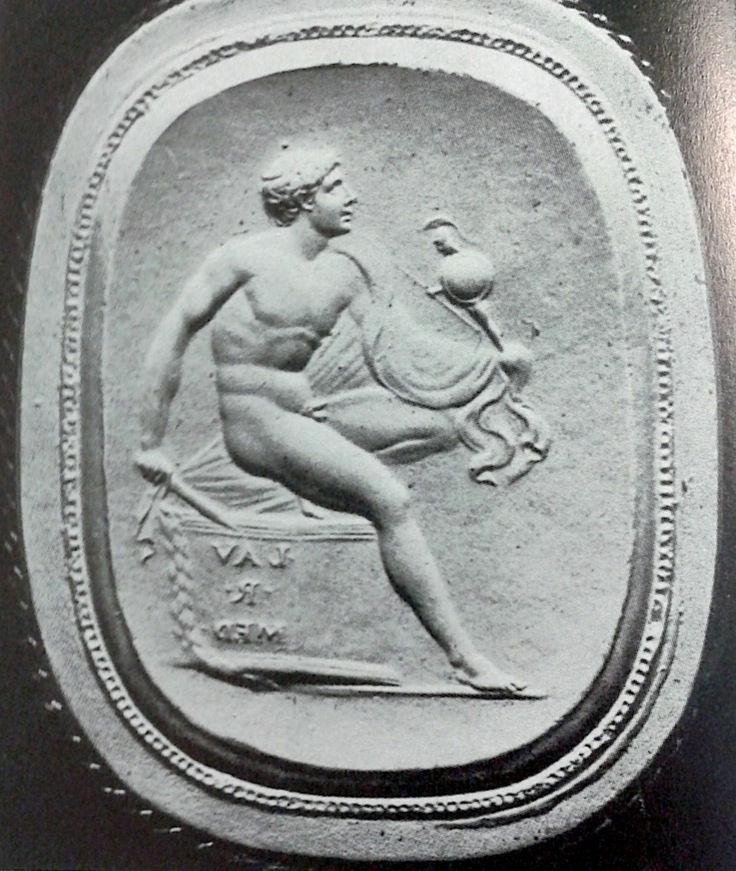

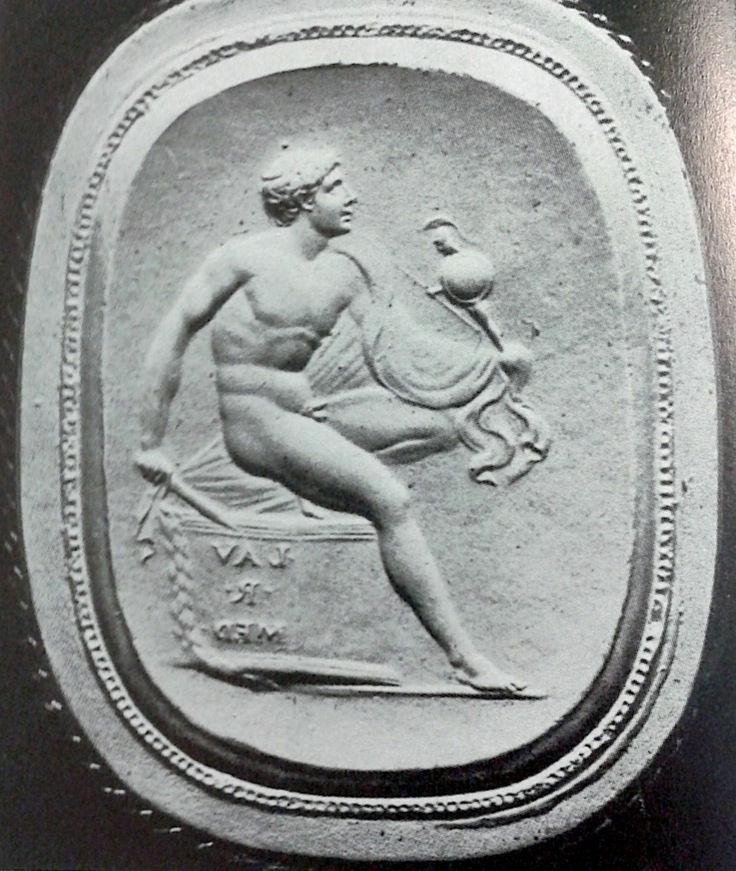

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM  We may say: as a byproduct the German art historian Ulrich Pfisterer did identify and virtually reconstruct a 15th century act of attribution as to an unsigned work: in his 2002 thesis on Donatello, which is also on how Donatello did compete with the legendary Greek sculptor Polykleitos. We may take the act as a mark to work with and call this mark a historian’s possible ›first encounter with modern Western connoisseurship‹. It is about a gem that the humanist Niccolò Niccoli, probably shortly before 1429, bought from a Florentine street boy, and about a possible and likely relating of that gem, which is extant only as a plaster cast, to another one signed, of which we know of and have, although we don’t have the original either, an image (see above background picture). Thus it is about formal analogies, and Pfisterer reconstructed this scenario, having a deep knowledge of Renaissance textual sources and of images, and also of images of works of art that happen to be lost). Indirectly it is about how the 15th century cultures of the Renaissance saw the Greek sculptor Polykleitos (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polykleitos), but this does less concern us here. Than it does concern us the mere act of attribution of an unsigned work: a point of reference for every (visual) history of connoisseurship, and, again, a point of reference to work with (see: Ulrich Pfisterer, Donatello und die Entdeckung der Stile 1430-1445, München 2002, p. 187-191, p. 580 and p. 592; pictures here are taken thereof by me). We may say: as a byproduct the German art historian Ulrich Pfisterer did identify and virtually reconstruct a 15th century act of attribution as to an unsigned work: in his 2002 thesis on Donatello, which is also on how Donatello did compete with the legendary Greek sculptor Polykleitos. We may take the act as a mark to work with and call this mark a historian’s possible ›first encounter with modern Western connoisseurship‹. It is about a gem that the humanist Niccolò Niccoli, probably shortly before 1429, bought from a Florentine street boy, and about a possible and likely relating of that gem, which is extant only as a plaster cast, to another one signed, of which we know of and have, although we don’t have the original either, an image (see above background picture). Thus it is about formal analogies, and Pfisterer reconstructed this scenario, having a deep knowledge of Renaissance textual sources and of images, and also of images of works of art that happen to be lost). Indirectly it is about how the 15th century cultures of the Renaissance saw the Greek sculptor Polykleitos (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polykleitos), but this does less concern us here. Than it does concern us the mere act of attribution of an unsigned work: a point of reference for every (visual) history of connoisseurship, and, again, a point of reference to work with (see: Ulrich Pfisterer, Donatello und die Entdeckung der Stile 1430-1445, München 2002, p. 187-191, p. 580 and p. 592; pictures here are taken thereof by me). |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM 16th Century: Writing Art History: Dong Qichang (not to mention Vasari) |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM The beginnings of art history are intimately intertwined with local and regional patriotism. This is not the only aspect that would it make interesting to compare the work of Giorgio Vasari and other European founding fathers of art history with the work of Chinese scholar and artist Dong Qichang (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dong_Qichang). Also a painter (like Vasari) Dong Qichang provided the Huashuo (›Conversations about painting‹) that comprise also – I am relying here on the book by the late Mary Tregear (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Tregear) on Chinese Art – a commentary, introducing collectors to criteria of connoisseurship and to rules of classification. Any history of connoisseurship has to take this work into account, at least any history of connoisseurship that prefers the cosmopolitan viewpoint to the only local one. |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Circa 1600: Frans Francken II Juxtaposes ›Connoisseur‹ and ›Iconoclastic Ass‹  (Picture: kunst-fuer-alle.de; further reading: Stephan Kemperdick/Johannes Rößler (Ed.), Der Genter Altar der Brüder van Eyck: Geschichte und Würdigung, Petersberg 2014 (exhibition catalogue Gemäldegalerie Berlin) |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM 1753: The Encyclopédie Defines What is a ›Connoisseur‹  (Bg picture: exurbe.com) |

Don’t miss, by the way, the articles on ›Connoître‹ and on ›Connoissances‹ for the historical atmosphere.    (Pictures: equitationpassion.chez.com; animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu; pinterest.com; animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu; bg picture: exurbe.com) |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM  19th Century: One Ingredient of Rumford’s Soup – a Critique of Connoisseurship (Picture: Gestumblindi) |

Invented in 1795 by Benjamin Thompson, Reichsgraf von Rumford, as a soup for prisoners, the Rumfordsuppe (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rumfordsuppe) became generally known and in use as a nutrition for the poor. And in 1834 Austrian painter Joseph Anton Koch (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Anton_Koch), inspired by the Rumfordsuppe, cooked and published his Moderne Kunstchronik, a satire on the art world of his time, a critique, wherein also ›overwise connoisseurship‹ does figures among the ›deadly sins‹. Full title: Moderne Kunstchronik. Briefe zweier Freunde in Rom und der Tartarei über das moderne Kunstleben und Treiben; oder die Rumfordische Suppe. If ›Tartarei‹ does ring a bell – quite right, the book was of not a little inspiration to Italian connoisseur Giovanni Morelli’s later appearance as Lermolieff (whereas in Koch, a desperate painter, fleeing the European art world, seeks refuge in Russia’s steppes, respectively Siberia. Given this (generally forgotten) background the entrance of Lermolieff quite rightly might appear as a comeback of (overwise) connoisseurship.

(From Moderne Kunstchronik, the painter »Christoph aus Manchester« speaking, who is the one who flees to Russia and Asia, his postal address being for the moment the address of the ›court trumpeter of the Dalai Lama‹; p. 47ff.; slightly modernized text; picture below: pinterest.com) (From Moderne Kunstchronik, the painter »Christoph aus Manchester« speaking, who is the one who flees to Russia and Asia, his postal address being for the moment the address of the ›court trumpeter of the Dalai Lama‹; p. 47ff.; slightly modernized text; picture below: pinterest.com) »Die überkluge Kennerschaft. »Die überkluge Kennerschaft.Der Kritiker oder haarscharfe Kenner unterscheidet sich von dem Ästhetiker oder Kunstschreiber, mit dem er durch gleiche Federfertigkeit verwandt ist, durch höheres Alter, tiefere Forschung, mehr Gelehrsamkeit, tiefere Gediegenheit, gerunzeltere Stirn und gravitätischeren Anstand und Würde. Anbei füttert ihn ein gutes Amt oder er lebt von seinen Renten, hat folglich ein gutes Auskommen, ist wohl sogar reich und hat nicht nötig, wie der ästhetische Kunstschreiber oder Lockvogel der modernen Schönheit, seinen Bissen Brot von dem Parnass zu holen, Kunstlieder anzustimmen und das Publikum für diesen oder jenen einzunehmen. Dieser haarscharfe Kritiker ist also ein ganz anderes Wesen, voll unergründlicher Gründlichkeit, Tiefe, Gediegenheit und Umsicht, kritische Flöhe zu knacken. Gewöhnlich sind diese Klügler schon bei Jahren, sprechen selten, aber wenn sie den Mund auftun, kann selbst das Orakel von Delphi schweigen. Eine vorhergehende tiefe Stille verkündet wichtige Sentenzen und entscheidende unfehlbare Urteile. Der nur im Nebel faselnde und fuselnde Kunstschreiber bekümmert sich nicht so sehr um den technischen Teil der Kunst, sondern voltigiert lieber die Kreuz und Quer auf dem Pegasus. Der überkluge, den kleinsten Fleck bekrittelnde Kenner durchsucht mit der Brille auf der Nase nicht allein die poetische Erfindung, er dringt auch durch die ganze Technik, durch die geringste Ader der Kunst, gleich dem Gift der Klapperschlange. Hat er Geld, so macht er zuweilen auch den Mäcenas, ist der Enzyklop der genannten und behandelten sieben Abteilungen [of the art world], macht den Künstler und Kunstdespoten, besonders wenn es etwas zu beissen gibt. Öfters sind solche Präsidenten und Kunstprotektoren bei den Kunstakademien, halten dort bei wichtigen und feierlichen Gelegenheiten gehaltvolle Kunstreden, beziehen gewöhnlich kein Gehalt für ihre Mühe, wie die untergeordneten Kunstbehörden, Direktoren und Professoren, es ist ihnen schon damit gedient, den kritischen Ehrenmantel um zu haben. Diese Ordenshändler lassen sich von den untern Kunstbehörden nicht lumpen. O Apollo, wirst du nicht schamrot über solche Kunstcanaille, welche dir amtspflichtig dient, und nicht begeistert entgegen jubelt! – Diese scharfen Kritiker sehen die Kunstbehörden und Künstler sogar als Maschinen und Ouvriers an, welche sie zu regieren allein die Kraft und Kenntnis besitzen. Sie sind, wie schon gesagt, der Inbegriff der modernen Kunstweisheit und glauben, obschon blitzdumm, die Weisheit der Minerva zu besitzen, und mit den Grazien und Musen vertrauten Umgang zu haben und stehn den Künstlern ratend zur Hand, damit Arm und Beine schulgerecht, wie sie es nennen, und jeder Haarwuchs genau am rechten Fleck sprosse. Ihre Eitelkeit lässt sich herab, dem Künstler in höchst eigner Person die zu korrigierende Stellung mit Empfindung vorzumachen. […]. Eine andere Rasse von jenen scharfen Kennern bekümmert sich mehr um das Materielle der Kunstwerke, [sie] sitzen tagelang bei den Bilderflickern, indem sie nur die spekulative Seite der Kunstwerke kennen; diese sehen vorzüglich nach dem Machwerk, erkennen jeglichen Meisters Manier und Strich, und sind darin schwer zu betrügen, obschon sie von dem poetischen Wert der Kunstwerke keinen Fuchs verstehn, sie wissen nur, von wessen Hand dies oder jenes Werk ist, welches die Welt erfreut, und wie es zu doppelten Preisen zu verzinsen, zu verkaufen und wieder zu kaufen sei, stehn in genauester Verbindung mit den Bilderflickern und nehmen übrigens eine eben so würdige und ernsthafte Miene an wie die eben genannten grundgelehrten Kenner. – […]«  |

20th Century: Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich   (Pictures: geschkult.fu-berlin.de; v-like-vintage.net; bg picture: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H02648: München, Goebbels im Haus der Deutschen Kunst)   |

I don’t know whether German writer Hermann Lenz’ novel Neue Zeit (originally published in 1975) is popular among art historians. It should be. Because it does not only convey what it meant to study art history in Hitler’s Munich in 1937ff, but does show the central personality Eugen Rapp, Lenz’ alter ego, learning (how) to see. And there are complicated intertwinings between learning (how) to see art, and learning (how) to see the political, social and cultural context wherein the studying of art does happen, and wherein Eugen Rapp has to find his way. And in the end it is about finding an ethical and human stance, in spite of (almost) everything, a stance that is based on and cannot be thought without: acutest observation. Which also means: that ethics go along, or might and should go along with acutest observation, might it lead to actual and active opposition or, as in Lenz’ case (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermann_Lenz): to inner opposition and to the self-given task of preserving a memory. Of what it meant to learn to see (or not to see).

| Eugen Rapp is meant to prepare an essay on renderings of Apollo by Dürer, but he is not doing this with actual inner participation. The connoisseurial problem (the hatchings, the dating) does not concern him – what interests him right now is the getting to know more about a female student (his future wife), who is studying with him (but sitting right now somewhere behind him, so that, while he is supposed to read Flechsig’s monograph on Dürer, he is becoming an eavesdropper). The person we are introduced to, from the beginning, is keen to read the signs. Coming from Heidelberg where his Professor got suspended, he has been accepted by Professor Hans Jantzen (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Jantzen ; http://kg.ikb.kit.edu/747.php) – on the tz of his signature you might rip your hand bloody –, a pupil of Adolph Goldschmidt. But who can be trusted? His Professor? He is not sure about the stance of his Professor (and neither was Post-war Germany, because Jantzen got suspended shortly, but reinstated in 1945 as a Professor). And one does warn him that his girlfriend to be is, by Nazi definition, half-Jewish. |

| This is all autobiographical, and, no doubt also that this, so far, is nothing but the truth. But of course one might ask now, if this is indeed ›teaching of history by means of literature‹. In other words: how much hindsight fallacy, how much knowledge in retrospect might be in there (and some critics went as far as to blame Rapp/Lenz for a supposedly only alleged innocence, because, later in the novel, as a soldier, Rapp still appears to be and to remain, in that view, ›all too‹ innocent)? The question is legitimate (while unfounded allegation is not): From what perspective is this novel being told? From someone knowing better, but only after the facts? One could’t say that Rapp actually does know things. In 1937. And one might imagine him choosing lectures and seminaries from the actual choice (see here: http://kg.ikb.kit.edu/821.php). He is not knowing, but still learning, tumbling also, and realizing that things, that already are complicated, will get more complicated any time soon (and with some pride he does realize that his girlfriend to be is indeed half-Jewish: which means that with some pride he does acknowledge things getting more complicated, because, probably, he does interpret this as a confirmation of his own, at least his envisioned own stance). And by what measure he might appear innocent? By not getting his hands more dirty than he is forced to, later, as a soldier? One might, if reproaching would be on one’s mind, also reproach his for not being more active in his resistance. |

| The novel does raise such questions that not necessarily are meant also to be answered by that very novel. And it is not about checking the novel for historical inaccuracies here, or for the perspective a novelist (who is also writing autobiography) has chosen. Because here, we would only like to recommend this very novel for anyone interested in what it meant, or what it might have meant to study art history (while trying to enter a life), and what it might have meant to learn to see in 1937, the year of the ›degenerate art‹ exhibition at Munich (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entartete_Kunst_%28Ausstellung%29), thus: in Hitler’s Munich. |

Further reading: Jutta Held, Kunstgeschichte im ›Dritten Reich‹: Wilhelm Pinder und Hans Jantzen an der Münchner Universität, in: Kunst und Politik 5 (2003), Schwerpunkt: Kunstgeschichte an den Universitäten im Nationalsozialismus, p. 17–59; Nikola Doll / Christian Fuhrmeister / Michael H. Sprenger (Ed.), Kunstgeschichte im Nationalsozialismus. Beiträge zur Geschichte einer Wissenschaft zwischen 1930 und 1950, Weimar 2005 |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM The Future: Connoisseurship in 2666  (Picture: Solaris DVD) |

We report from the International Art Historical Congress of 2666, held on the Propeller Island in international waters, and upon readers demand, we report from the Rembrandt Research Platform very in particular (see picture above, showing all, not only the present, but also the former members of the much debated Rembrandt Research Project who had gathered on this very occasion).

»Why does the picture commonly known as The Syndics of the Draper’s Guild (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syndics_of_the_Drapers'_Guild) not figure any longer as a Rembrandt?«, the elder Dutch gentleman from the Rembrandt Appreciation Society wanted to know. From any member of the panel, upon which he made a challenging and at the same time very dismissive gesture.

One knew his monologues here already, on this very platform; nevertheless the panel was in trouble, since one had mistakenly given the only microphone away that had now been passed to the enraged gentlemen who, triumphantly, awaited an answer (although he was in possession of the only microphone).

»But can’t you see that the painter of this picture painted a parody of Rembrandt?«, one member of the very panel was about to say, but now the actual monologue of the elder gentleman got going.

»And doesn’t it seem impossible to you as well that Rembrandt would have provided us with a parody of himself?«, the Professor in the back thought for himself, but all in vain.

Hardly understandable, the elder Dutch gentleman now pointed out that Rembrandt was actually one of the few painters that he could imagine of having painted of parody of his own style (he obviously had read the books of every member of that panel and was therefore prepared for any feud), that actually Rembrandt was one of the godfathers of Postmodernism, an obscure philosophy that – obviously – no member of the revered panel had ever heard of (but in the Rembrandt Appreciation Society had become very fashionable).

Some confusion was brought in, for a moment, by the contribution of a PhD student, who now, in turn, was claiming, and in a way supporting the board, that even the century was completely mistaken and that the picture depicted in fact a legendary panel at the 2014 Authentication in Art conference that had been held at The Hague (technical analysis had proven this, not to mention iconological research).

But this was now too much for the members of the panel, and life reverted to them (our picture does in fact show the very moment before life reverted to this actually equally belligerent group).

And in shouting one of the panel members made now clear (at least to the rest of the audience) that the hats might be in accordance with that decade, but not at all the beards and hairdos.

Upon which the elder Dutch gentleman, now ostentatively, and not without ironic triumph, nodded.

(18.11.2014; with thanks to Zadie Smith)

PS (19.11.): A reader does inform us that, in the meantime, an inscription has been found, proving that the picture does actually show the 2220s Rock Band The Martian River Pirates (a ZZ Top revival band) at a press conference. And more than that: We are also informed that the picture does render the very moment – which, I might say, brings our story to an even better end – when the band was being asked, I quote, ›… but why do you all dress up as Rembrandt?‹.

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Connoisseurship in 2666 |

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS