M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Flaubert at Fontainebleau |

See also the episodes 1 to 6 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

And:

Flaubert at Fontainebleau

(12.7.2021) We had begun our journey, our intellectual adventure, at the Vatican. Now we have reached Fontainebleau,

a key site for Salvator Mundi studies. And Fontainebleau (picture above: Nathan Hughes Hamilton) is also Flaubert territory.

I am not going to visit Fontainebleau without the works of Gustave Flaubert in my (virtual) luggage, nor without being aware (and making

everyone aware) that Fontainebleau is Gustave Flaubert territory. And what a luck this is. Since Gustave Flaubert,

French novelist and among the greatest novelist of all times one of the greatest, is kind enough to provide us with

his perspectives. On Fontainebleau, on doing history, on the Renaissance cult in particular (including its stupidity

and superficiality) and, yes, on the Salvator Mundi debate. Since Flaubert, the disillusioned collector of his age’s

stupidities, is also the disillusioned collector of all modern age stupidities. Since (as his disillusioned readers know)

nothing has changed. But it is important to note: Flaubert knew about the vices of his age, since many of them (perhaps all)

had been his own. Well then – here comes the seventh episode of our New Salvator Mundi History.

One) Contemplation, Calm and Happiness

The novel Sentimental Education by Gustave Flaubert (1869) is probably not the first pick of those people (insofar they read

novels at all) that have dedicated their lives to the vita activa.

But it is certainly a first pick of those who are sceptical as to the vita activa in general and have dedicated their

lives (insofar this is possible) to the vita contemplativa. It is a disillusioning novel about people (often called

mediocre by critics) that fail as to most of their aspirations; but what the reader gets is a tableau, a panorama of

human activity (and failure) like few others. The panoramic view Flaubert provides us with in the third part of the

novel, I would like to call the heart of this novel: it shows the revolution of 1848 in Paris, after which two of the

main protagonists leave Paris for the countryside. These two, Frédéric Moreau and Rosanette, visit Fontainebleau, after

having experienced the revolutionary Paris; and after having visited the chateau, after embarking to the forest of

Fontainebleau by coach, they experience, for moments, probably due to escaping time and space for moments, but also due

to nature and due to an opening up of the protagonists towards each other, a certain happiness and calm. What we get, in

more general terms, is a panorama of people (chaotically) making history, of people visiting the glorious but also vain

remnants of remote history (the chateau of Fontainebleau), for which the two, being tourists, have actually only a faint

interest, and finally of pure escapism (while, in Paris, the revolution goes on), providing, at least for some short

moments a certain happiness and calm. But it is important to note that Flaubert’s protagonists have only a faint

awareness of what they are actually experiencing (as the famous and notorious ending of the novel does show), and certainly

not the awareness a reader might get, due to contemplating the protagonist’s experiences. This kind of happiness is left

to the reader and that of readers.

Two) A Princess Being Outshadowed by a King

What Flaubert shows us in the Sentimental Education are people having only a superficial interest in history while

visiting a historic site. What Frédéric and Rosanette are concerned with is their inner life, their personal history and

their relationship. The opposite, the fiery passion, in fact, the historiographical obsession, Flaubert knew only too

well as well (he caricatured such – temporary – passion at the end of his life in his unfinished project Bouvard et Pécuchet),

but he shows us, while visiting Fontainebleau in the Sentimental Education, a superficial encounter with the past,

the delving into the atmosphere of a historic site. But one should not be mistaken: the ghosts of the past are there,

for Flaubert as for the protagonists, even if these ghosts are outshadowed by the personal demons of the protagonists,

as one might say; the ghosts of Francis I and of Charles V, for example, are there, the ghosts of kings and

concubines, but the encounter is not as intense as it might be for someone just experiencing an obsession for history,

for the mysteries of Fontainebleau and, yes, for its ghosts.

We have few first hand sources as to the childhood of Henrietta Maria, supposed owner of the

Salvator Mundi version Cook while living in England as the wife of English king Charles I. Born in 1609, her father,

French king Henri IV, was murdered in 1610. Her eldest brother, a child like her, immediatedly became king as Louis XIII.

Henrietta Maria was married to Charles I in 1625. These are the rough dates we have to deal with as to the childhood of a princess.

We have few first hand accounts for Henrietta Maria, but we have one for her brother, the king, a source which is quite

spectacular, since it brings the ghosts back to life. It is the journal of the king’s doctor, Jean Heroard, who was

observing the king’s health, the upbringing of the king, quasi day by day. But Henrietta Maria is outshadowed by her

brother, the king, who, later, got in conflict with their mother, Maria de’Medici, whom he banned from Paris for some

years. Henrietta Maria was not in the focus of Heroard, and if we have questions, these questions remain largely

unanswered. When she got born, in 1609, her brothers and sisters were already there, as shows the 1607 picture by Frans

Pourbus the Younger above on the right.

Let’s name some of the questions we have, not all of them: who did provide for the religious upbringing and instruction

of Henrietta Maria, who was to become an advocate of the Catholic faith in England when living in Whitehall? What was the

role religious pictures had during that upbringing? How was the religious upbringing of all the princes and princesses

organized? Finally: where exactly were the pictures? And what memories were brought back, when Henrietta Maria, in 1644,

visited Fontainebleau again?

Three) About Provenance Research, About What It Is Not, And About What It Could Be

Our intellectual journey had begun in the Vatican. After that we had visited the Louvre, the Prado, Amboise, the chateau

of Chambord, Conques, and now the chateau of Fontainebleau. But my personal journey with the Salvator Mundi had actually

begun in 2016, when I had tried to develop a tool for Salvator Mundi studies. A survey of all the versions did not exist

(why not?), and I came up with this particular layout. And

I tried to draw the attention

to the picture of a young Christ in the Pushkin Museum of Moscow (picture above: sailko), which had a provenance

that linked it with Charles I, Henrietta Maria’s husband. Advised by me Ben Lewis elaborated on that in the following,

developing also a passion for provenance studies and delving deep into the history of that picture. Which meant also:

deep into the history of the Russian countryside, the Russian country estate, where, for some time, this picture was

kept by its owner (a scenery, by the way, redolent of the atmosphere of Tolstoy’s War and Peace).

What I tried to do in 2016 was also to draw the attention to what provenance history could be, apart from its utilitarian

purpose and use: and it could be exactly what Flaubert practices in the Sentimental Education: its purpose could be

to provide us with a panorama, a tableau to contemplate. The Pushkin Salvator ›experienced‹ exactly what the protagonists

experience in the Sentimental Education: the revolutionary chaos, but also the calm and the escape from ongoing

turmoil. And if this is not provenance research in the conventional utilitarian (and yes, also bureaucratic) sense –

this is exactly what provenance research could be. It could provide us with: 1) a sense of the embeddedness of works of

art in history, be it revolutionary or not; 2) the possibility to comtemplate art in changing historical context, if only

this context would be illuminated more; and 3) with the light this may shed on various works of art and the ways they could

be seen by various contemporaries.

Maria de’ Medici, by the way, is said to have been the owner of the Hermitage Flora, attributed to Francesco Melzi.

Did she bring that picture to France? Did she had it bought in Italy for her? Or was it already in France, due to

Leonardo’s stay in France, and the supposed selling of pictures to the king, handled probably by Salaì?

This brings us back to say that provenance research, as one way of doing history, runs also in all dangers historiography

can run into, and while this problem is rarely ever addressed: we should be reminded that provenance research, today,

is mainly done for three reasons: for the purpose of the art market, for the noble aim of restitution of stolen art

works, and for the purpose of general documentation, whatever its exact purpose my be (sometimes it is just routine).

Generally it is not practiced in the sense we are practicing it here: for contemplation’s sake (for the contemplation of

history and art history), and especially for the contemplation of the reception of art in general. We may run into the

danger of developing obsessions in various ways. But we should also become aware of that and recognize: what we should

not practice is historiography according to the interest of one particular party. This would not be worthy to be called

historiography – this would be advocacy, based simply on bad scholarship (and any scholarship that does not develop a

sense for its dangers, for the danger of bias in the first place, is bad scholarship). Perhaps bias, confirmation basis

can never fully be avoided, but we should seek to do so, and in most Salvator Mundi studies, sadly, we are lacking such

sense, and such awareness.

Selected literature:

Carolyn Harris, Queenship and Revolution in Early Modern Europe. Henrietta Maria and Marie Antoinette,

Houndmills/New York 2016

Priscilla Roosevelt, Life on the Russian Country Estate. A Social and Cultural History, London 1995

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

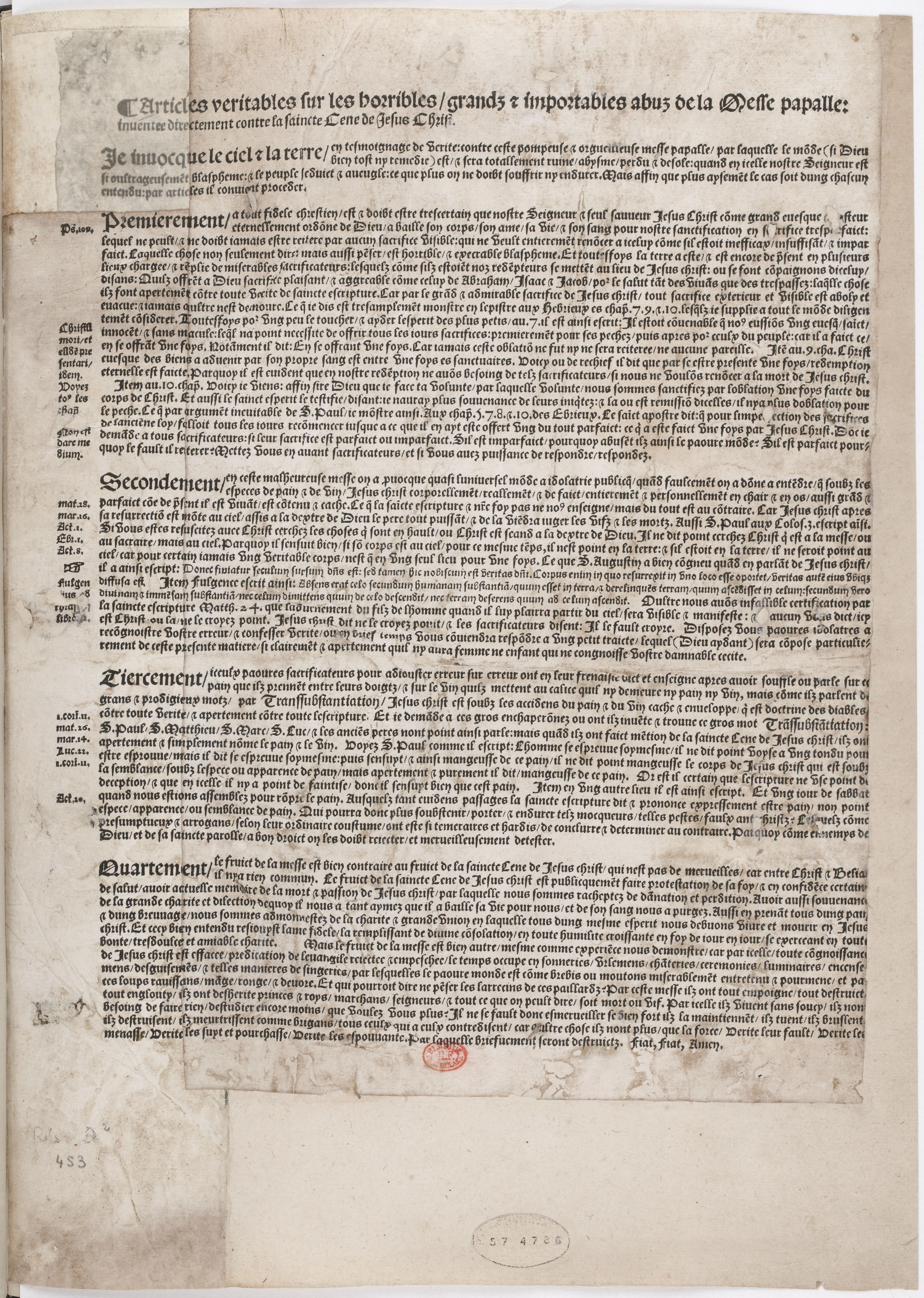

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

Here we look at another Valois court style portrait. This time it is Caterina de’ Medici being represented (c. 1536), who was married to the second son (Henri) of Francis I (the future Henri II). And if you would think that she might have been the one who might have brought a Salvator Mundi painting with her, from Italy to Fontainebleau or other places associated with the French monarchy, it is the green background, here as in the (virtually reconstructed) Salvator Mundi painting that makes this rather unlikely. Or do you think she might have brought a real treasure with her, a painting by the master of masters, Leonardo da Vinci, and she did allow that such untouchable masterpiece was retouched in green by a Valois court artist? Only to have it match with the background colour of (many) official Valois court style portraits?

See also the episodes 1 to 6 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS