M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

The Digital Lermolieff

MacPaint 2.0 screenshot (picture: JoshuacUK; small picture above: Alexander Schaelss)

To begin with a little bit of personalized computer history: According to Blickfeld no. 23, edited in 2012 on occasion of »40 Jahre Gymnasium Oberwil« (this happens to be the Swiss Gymnasium that I did attend to make my school leaving examination [Matura] in 1990), it was in 1986 that a computer lab with 11 Macintosh computers (probably Macintosh plus; see small picture above or: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macintosh_Plus) was equipped. We were instructed by our math teacher, Mr. Hansueli Wittlin (http://gymoberwil.educanet2.ch/wittlinh), and not only instructed, but also encouraged to explore these computers not only in our formal lessons, but also in our spare time (if we were to find any), because, as I do believe to recall, and as certainly Mr. Wittlin had very well understood – it was about to learn and to practice an intuitive handling of these machines, and less about to gain a deeper technical understanding of the hardware, or of the software that was running on these machines (this was for the chosen few).

Why coming back now to these early days of Macintosh computer history? It’s because of my recalling that I mainly filled the time that I did spend in this very computer lab with playing around with and to create a picture on MacPaint, a picture (an early computer painting, if I may say so) that somewhere lies buried on a early days Macintosh storage disc that probably no machine will ever be able to read again (and be it only for the reason that I have no inkling if and where this disc was still in existence).

One thing is for certain: we had this program (and probably also MacWrite), and the MacPaint software, as I am learning from Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MacPaint), was sold until the year of 2004. And the year of 2004 is exactly the year when, for the very first time, as I do believe, the computer as such had developed to such elaborate qualifications that the Neue Zürcher Zeitung chose as a subtitle to an article »Der Computer als Kunstkenner« (›the computer as an art connoisseur‹: http://www.nzz.ch/aktuell/startseite/articleA1JMI-1.349390), and this article was about attempts to authenticate paintings, or at least to help in the authenticating of paintings by Pieter Brueghel the Elder and Perugino, by using, or better: experimenting with a newly developed computer application, meant to analyze the particular brushwork of already authenticated paintings and to compare these patterns found in original works with others works in question. The computer, one may say, in 2004 had not only developed to be a machine to be painted with, onto a monitor screen or into a storage, but also to a machine, able to possibly help the art connoisseur in his attributional work. In sum: it seemed or it seems that the computer has developed or will be developing its own eye(s).

We might still be in middle pharaonic times as to the computer being able to attribute works of art on his own, but the history of the computer being a tool or aid, an aid possibly being of help as for various routines of applied stylistic criticism, has developed to a point that I find that it would make sense to look back, in order to contemplate these recent developments and to reflect upon what exactly is a computer being able to do today (in connoisseurship or as a connoisseur) and to what future developments this all may lead one day.

One might wonder if such a contemplation could also be of actual, of real benefit as to a real development and design of respecting new digital tools, and the character of what’s following is certainly experimental. I have chosen as a title to this section the words ›digital‹ and ›Lermolieff‹ (and to be sure, I hereby do claim also a copyright as to this brand and as to the thoughts associated with it), because this experimental section will be about an attempt to think the methods of scientific connoisseurship through again, but now transposing these methods to the digital field. I have no actual ambition at the moment to help developing any computer application called Digital Lermolieff, but the mere intellectual attempt to think the Morellian method through again as if it was to be transposed into the digital age and area, will be of not a little benefit at least to clarify as to how this method was meant to work, and as to what this method (and applied stylistic criticism as such) is all about (and also will be in the future). Since many misunderstandings as to the Morellian method do exist, scientific connoisseurship, as I do believe, will only be able to develop further, be it in the digital area or outside, under the condition that the respecting misunderstandings would be left behind. Again: I do claim a copyright as to what’s following, and I am open to discuss the Morellian method and other approaches to rational applied stylistic criticism with any programmer or entrepreneur, and be it only for the reason, again, to clarify what does make sense (or will or might), and what doesn’t (respectively: won’t or might not).

The Digital Lermolieff

ONE) The Various Levels of Applied Stylistic Criticism: Clarifying the Target

If a computer is meant to look at pictures we got to tell him what he (or it: the machine) is supposed to look at, since, as we all know, the machine does not know for itself what to do at all (unless a platform of artificial intellgence will begin to think for itself, including to decide what to look at).

That we have to tell him is good because this is forcing us now to clarify what applied stylistic criticism (the notion that I am going to use henceforth instead of ›connoisseurship‹) can be or should be about.

Is there a question at all?, one might ask now, and yes, indeed there is one. That is: there are several questions. And if you happen to listen into the conversations of for example 19th century connoisseurs, you will notice that there were delicate ideological gaps, dividing certain camps. It was not only about the question if one was to aim at a rational or even rationalistic procedure or not, at a transparent method, if one likes so; it was also or even more so about the crucial question on what level of visibility in pictures potential identifiers were to be found, identifiers helping us or even forcing us to relate names with pictures, to classify, or in one simple term: to attribute pictures to certain artists, respectively to their names.

When in 2004 analyses of brushstroke patterns were made, computerized applied stylistic criticism aimed at one level that one particular camp of 19th connoisseurs, namely the Morellian camp. did not very much like to look at. Why not? For one because one thought that one had found a better, a more promising approach that was targetting at another level of visibility, and secondly: because the looking at brushwork styles could be seen as being of little help, if it was about artists styles rather having disappear brushwork styles in a stylistic paradigm of, idealistically, crackless realism or even illusionism (visible brushstrokes, for example, do disturb and undermine a trompe l'oeil effect, if such an effect is wanted, and moreover: connoisseurs like Giovanni Morelli who had little own experience with drawing and painting themselves knew also rather little of artist techniques, and knowing of various procedures might also be a precondition to actually see and to identify such techniques.

So what was the Morellian approach about, if not about style in terms of brushwork and brushwork signature features of artists?

The target of the Morellian method was a totally different one. In simple words, it was about the individual imprint that an artist left on his own representation of reality, even if aiming at realism, illusionism or even trompe l’oeil. In brief: an imprint left, even if the artist worked realistically.

But at the same time it was not, or better: not always, or not always anymore about the obvious stylistic paradigm that a particular artist had developed. If thinking for example of a modern artist like Fernando Botero (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fernando_Botero) we will easily recognize an individual imprint upon the rendering of human figures, namely upon the rendering of anatomy. But this is not what Giovanni Morelli had in mind when he shifted the attention to the imprint that artistic individuality left on anatomy. Morelli took for granted that Renaissance artists, and he worked mainly on Italian Renaissance artists, aimed generally at realistic representations of reality, and had also developed certain stylistic paradigms like, one might say, a stage director is staging reality. One might think of how Leonardo da Vinci worked with light and shadow, and of other leonardesque signature features that were too obvious to base an identification of a picture upon such features, since whole schools worked within such paradigms and countless imitators also tried to work in such paradigms. And this is why Giovanni Morelli attempted to shift the attention of applied stylistic criticism to the very margins of such paradigms, to areas unburdened of stylistic expectations. And if we would think of Fernando Botero again, we would have to think about areas where a) individuality of Botero showed, but b) we had to find other identifiers than the more obvious imprint that artistic individuality left on anatomy.

To sum this up and at the same time to embed the said into a more generous framework as to what stylistic criticism is all about we might think of individual style as a layered phenomena. We have

a) the brushwork style, i.e. patterns as a result of artist hands movements (for example a dashed brushwork style, which means that a painting were made out of many, many rather small or short movements of the hand);

we have

b) on a representational level, i.e. on a level of the reality that is rendered in a picture: the main stylistic paradigm, the main individual imprint upon realistic representations, made out of various elements (stylistic signature features);

and also

c) marginal features, that, possibly, remain rather unnoticed, just because these features are usually not seen as being part of a stylistic paradigm;

and, more than that, we have also

d) the whole thinking, feeling and knowing of an artist that results in style, understood in a much more wider sense: in his artistic vision or creation or interpretation of reality, based on his knowing, thinking, feeling etc. etc. (and to work with such identifiers, of course, knowledge, empathy etc. is required).

Said this it is easy to understand that Morelli recommended in certain situations, namely if one was stuck with a, b and also d – rather to work with c, in order to obtain a higher level of certainty as to the attribution of a certain picture in question. And it is easy to understand now also that in 2004 first steps in computer-aided stylistic criticism were made, conceptualizing mainly a. With this said we can move on with thinking how to conceptualize c (and if we were bold, also b and even d).

TWO) What He Did Mean At All or: Giovanni Morelli’s Thinking Being Visualized For The Very First Time

Why do I dare to say that Giovanni Morelli’s thinking is being visualized for the very first time here? Isn’t this a bit bold? And aren’t his books scattered with depictions of hands and ears (that by the way are being reproduced again and again in Morelli literature and in the World Wide Web)? Isn’t this flood of hands and ears enough to visualize Giovanni Morelli’s thinking?

To the last question: a simple NO.

And I have chosen to demonstrate why with one particular artist: with Raphael.

First of all: If you would check the tables with depictions of hands and ears in Giovanni Morelli’s books for actually containing a Raphaelesque ear – you would find none. There was no such ear being included (the choice of artists being represented was rather small).

Secondly: If you would think that knowing about one particular shape of ear was enough for Giovanni Morelli to decide over the question if a painting in question was by Raphael or not, you have already misunderstood Giovanni Morelli on a most fundamental level (but unfortunately this was, and probably still is the banalized, trivialized understanding of Morelli, and in its trivialization this understanding is simply wrong).

Thirdly: Any historian of connoisseurship reading the actual sources of that history (that include, in Morelli’s case, a large body of letters) could know that Giovanni Morelli thought the illustrations to his books, the above mentioned tables with depictions of hands and ears, to be completely inadequate himself (to put it mildly). The history of these depictions is complicated and it might be enough to say here that Morelli, at the end of his life, was critical as to this illustrations. But no follower, no pupil of his (primarily the one who knew about Morelli finding these depictions inadequate: namely Jean Paul Richter) found it necessary to keep on working on this problem. Berenson probably knew nothing about Morelli being most critical as to the illustrations, but it would lead too far here to ask, if Berenson actually did understand how these illustrations were, according to Morelli, to be understood, and why Morelli himself found them inadequate (Morelli by the way, dismissed all the depictions stemming from his first actual book explicitely as being of little worth).

And now we come to the demonstration of why it is simply wrong and trivializing to assume that Morelli did recognize a particular artist ›by the ear‹ (if it is imputed that ›by the ear‹ means ›by a stereotypically rendered shape of ear‹). This is wrong because this understanding of Morelli does know nothing of the difference between ›basic type‹ and ›phenotype‹ (or ›specimen‹). A basic type being a mere construction, based on many found specimen, but still a construction, and a specimen being an individual belonging to a type (for showing – maybe only more or less – the characteristics of that type), but not exactly matching an idealized representation of a type (that’s being reduced to characteristics and does not show any accidental properties, that however, individuals do show in addition to their showing of characteristics).

Now back to Raphael. Because what one does find in Morelli’s books are mentionings of works that Morelli considered as being by Raphael, mentionings that even explicitly tell that these works (including portraits) would show what Morelli considered as being the Raphaelesque characteristics of rendering an ear. Of course this reference material that I have put together in the one image that follows here (below) does show, if we follow Morelli, renderings of ears that combine characteristics and accidental properties, in other words: the image that now follows does not at all show an idealized Raphaelesque ear (the one ear shape that one might think would be enough to know of), if one would expect now one to follow. But the truth is: no one ever found it necessary to continue Morelli’s work as to an improvement of visual demonstration of what it was all about, and no one cared that one, up to the present day, does know very little, on what actual visual demonstrations Morelli (and later Berenson) did base their attributions upon. And this despite the conventional understanding that this line of tradition does represent ›scientific connoisseurship‹. This line of tradition, one is forced to comment, has done very little as for making its own operating really transparent to the scientific community (not to speak of the general public), and it has also shown little inclination, if any, to reflect, self-critically, on how an inadequate visualization could be improved towards a better one (but we are forced here to think about what the whole approach was all about, while the mainstream writing on Morelli never did feel inclined to actually look at pictures with the eyes of Morelli and Berenson, because otherwise one would have long found and criticized what I am presenting here).

(Visualization: DS)

I do hope that everyone who’s looking at these three renderings of ears that Morelli explicitely does refer to in his books as showing the Raphaelesque characteristics, does think for a while on what Morelli did actually mean at all, subsuming these three renderings under one and the same type (one might ask: do these ears have something in common at all; or: what exactly are the common characteristics and what the more accidental properties; and does an artist produce at all such types that could be, possibly, used as being identifiers in the end, or as being simply clues); and I do hope also that this one image is capable of dispelling the one big misunderstanding associated with the Morellian method: that it was about stereotypically rendered two-dimensional shapes of ears (in other words: about shapes being repeated like a finger of a human hand may produce, with fingerprint-like stability, one and the same print). But looking back upon the history of the Morellian tradition, one cannot help to say that, if it does stand what I am saying here, that this tradition may not only have put connoisseurship on a more firm footing as especially the Berensonian tradition seems to believe, but it may also have produced misunderstandings that spreaded quite widely (if not the say: that produced also desasterous misunderstandings or, in one word: chaos). And as to the question how to visualize Morelli, we should like to continue a discussion that stopped in 1891, which means: with Giovanni Morelli’s death.

THREE) What to Teach a Machine?

In order to teach a machine anything one might be well advised to make one’s mind up as precisely as possible as to what exactly one wants one’s machine to do. Are we, at the present moment, enough prepared, to tell a machine how to become Giovanni Morelli, i.e. how to become Ivan Lermolieff? I guess that we are not. Not yet. And this not only because the subject matter is complicated as such, but also because, in the above section, we have raised a couple of questions that we have, alas, not answered yet. Hence let us do the following: let us zoom out of the picture that I am giving here and try, if only for a moment, a wider perspective. Before zooming in again, and before actually we try to emulate those mental processes that the Morellian method, better: the Morellian controls, i.e. the checking for particular formal characteristics in drawings and paintings, do involve.

First of all: let’s also enjoy what we are doing here. We are looking into the fascinating subject of how artists do create form, which is: we are also looking into the artist’s mind, and not only this: at the very same time we are looking into the fascinating subject of a connoisseur’s perception, and since, with a third eye, if we have one, we are also looking into recent (and maybe also future) technological developments, one might say that various worlds do meet here: the Digital Age meets the Age of the Romantics, since the underlying theory, not very visible but without any doubts being there, the underlying theory of why actually regularities in formal qualities of paintings (the one phenomena that we use to call ›style‹) can be found it all, the underlying theory of the Morellian method comprises the premise that an artist’s hand does, as it were, externalize the artist’s inner notions of, for example, human anatomy, when this very hand is painting human anatomy. In other words, and this is the point I am getting at, Giovanni Morelli was, without any doubts (but it is difficult to say to what degree) influenced by the Romantic philosopher Friedrich Schelling. And said this, one might feel also invited to question this very theory, or better: these rather hidden theoretical assumptions, as one might feel to be invited to question the Morellian method on any level and in general (and in my biography of Morelli’s apprentice Jean Paul Richter, I have tried to make a start and to enlist and to discuss the numerous problems associated with this approach).

Speaking of method, one has to remind once more that, if we are zooming in to analyze the Morellian checking for formal detail, we are zooming in only into a segment of Morelli’s connoisseurial practices, into an important segment, but still only into a segment; and if you would think that Morelli’s practice as a connoisseur was identical with an obsessive using of the Morellian method only, you would be, again, very mistaken. But it might be enough here to remind that Morelli was a sceptical and very pragmatic mind, who, depending on the situation, would apply any method, any aid, and any other approach to determine authorship, and not only, actually never: only, the method named after him solely (in fact, in an important but apparently well hidden passage, Morelli does maintain his conviction that attributions should not rest upon the arguing with Morellian details alone).

Now we are a little better equipped to again zoom in into a complicated picture. And we might now adress the question of the Raphaelesque ear again. What is it all about? Is is about a contour? Or about the mere fragment of a contour? Is it about how an ear is sculptured? Or simply: is there such thing as an Raphaelesque ear at all?

We have to ask Morelli himself to get answers, and we might begin (to the risk to make him angry) to raise a heretical question, namely the question if portrait-likeness does not ›beat‹ Morellian detail. In other words: if an artist is obliged to portrait-likeness, and above on left and on right we see details of two famous portraits, is there actually room for the artist to leave an individual imprint on the shape of the ear? And the very conviction of Giovanni Morelli indeed was that even in portrait the individual type of ear does show (the two details of famous portraits do figure here, just because Morelli included them on a list of portraits that, although being portraits, show such identifiers as the characteristic imprint that an artist like Raphael left, if we may say so, on a Pope’s ear and on a ›Donna Velata’s ear‹, even if adhering, at the same time, to portrait-likeness and to the rendering of a recognizable face.

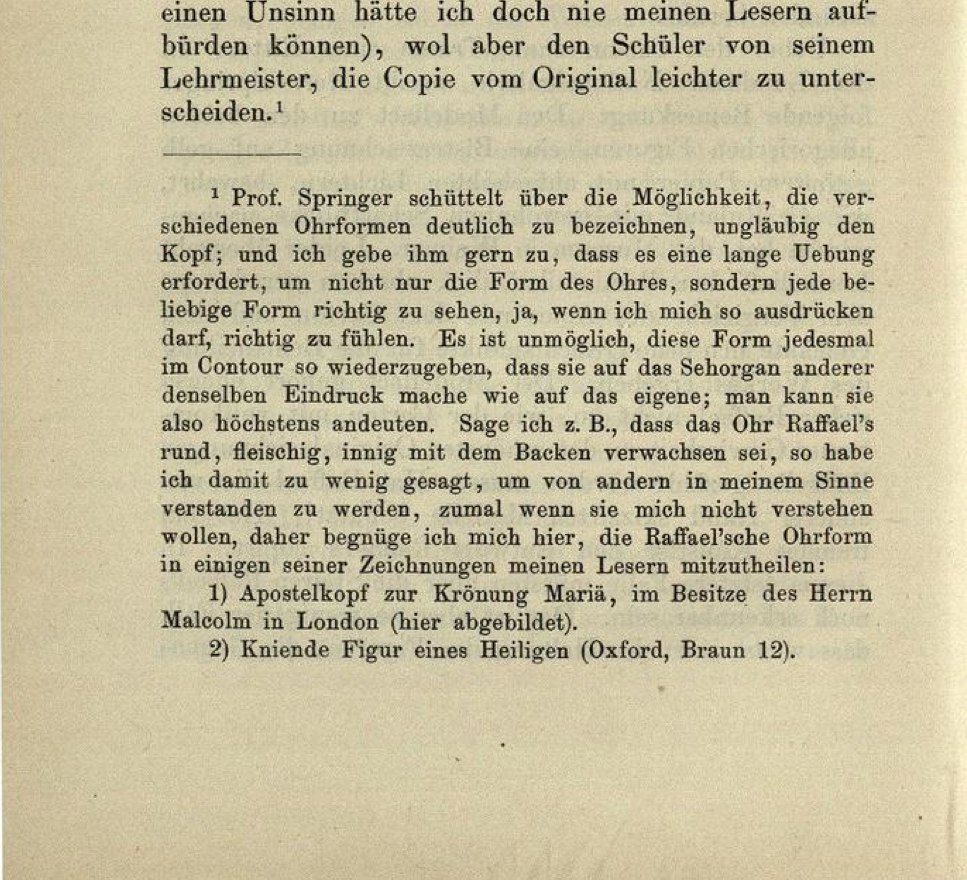

Now to the question of contour, and to the question of how to define the Raphaelesque type of ear: First of all, it is also but not only about the contour, which is: it is not about a single signature feature alone, and more important: one single example of an ear that, without any doubt, was painted or drawn by Raphael is not enough either to provide us with enough of information as to the Raphaelesque type of ear, and this for two reasons: for one, Giovanni Morelli distinguished various phases of how the artist Raphael did render an ear; and secondly, it was about a combination of features in which Giovanni Morelli saw the Raphaelesque type of ear being realized (in individual outshapings of the basic type). How do we know about that? Just by reading Morelli speaking about the Raphaelesque type of ear, but speaking only in German, since the very passage (shown below) is from one of his essays on Raphael that were yet included into volume 3 of the German edition of his critical studies (Morelli 1893, posthumously edited by Gustavo Frizzoni, and it is page 318 shown below), but not included in any translated edition.

And as usual, as if not wanting to lay all his cards on the table, Morelli remains very ambiguous. And most important: never he does visually define his notion, his vision of the Raphaelesque type of ear – he does only speak about it, and he does give examples, but never a basic type as such as an illustration, while in other cases he had someone draw such basic types (actually it was the restorer Luigi Cavenaghi, but Morelli was puzzled because Cavenaghi seemed not to capture the type as Morelli saw or had made up his mind about the type; and Morelli then addressed someone else, namely Jean Paul Richter, also to draw such types, explaining that for the layman better to understand, these visualizations had to be ›slightly caricatured‹, and about this point, the actual discussion about a proper visualization ended). In brief: in our testcase (Raphael) we know of examples that Morelli considered as being individual realizations of the type, we also know that Morelli described the type as being ›round‹, ›fleshy‹, ›intimately intergrown with the cheek‹, but he leaves us with this. To make up our mind ourselves as to how construct the basic type. And this basic type, we’ve come full circle, of course we do need, to teach a machine of how, according to Morellian principles, check a painting for the Raphaelesque type of ear (whatever we, or the machine subsequently would make with the results of such a checking). And why we do need such a type? Because the artist, any artist, does not render one and the same shape with robot-like precision. If an artist does, as the theoretical assumptions suggest, realize an inner notion, he does so not with fingerprint-like stability, but rather with signature-like variation. We do need a type, because there is variation, and the more examples we do have of individual realizations of an inner notion, the better our understanding of that notion.

But although Morelli leaves us with fragments of informations, we have enough of informations to proceed. We do know that it is not enough to scan just one ear from an authenticated work by Raphael. We would have to collect as many examples of ears from all phases of Raphael, and we would have to construct a basic type of ear for each phase, to have a reference, and also a timeline for any new comparison. And I would also say that we would need a three-dimensional model of the Raphaelesque type of ear, since, given that the artists does indeed externalize, with some regularity, a certain type of ear, he does so, again, not with fingerprint-like regularity. Once the ear might be seen in frontal view, in other cases only in perspective shortening; the characteristics might be only more or less outshaped (›being realized‹), or most simply: it might be, in one case, a child’s ear, in other cases a woman’s ear (or a Pope’s ear). Three examples of authenticated ears we see above, and the task of a Morellian apprentice (be it a machine or not) would now be to develop a notion (also a ›feeling‹, as Morelli says above; which might refer to a three-dimensional way of thinking, as for example medical students have to develop), as to the underlying type, underlying these three diverse examples. And our task would be also to somehow store that type in our imaginative memory, and to come back, in an appropriate moment to that content of storage.

We see here how processes of interpretation come into the checking for formal detail, but this is not just because we have to tell our machine what to do, these processes were only disguised and rather neglected in presentations and discussions of the Morellian method, eager to underscore its rational and scientific nature, but on various levels, without any doubt, interpretation comes in: not only in the distinguishing of the characteristic feature from the accidental, but also as to the degree of tolerance we are willing to practice: if subsuming an example to a type or not. And we see that this is much more complicated than simply to ask: does a fingerprint match. The very use of the fingerprint in association with the Morellian checking for formal detail is, in truth, an inmistakable clue that the complexity of the approach has not been grasped at all. It is, to say this again, not about the matching of stereotypes, but about the question: could a certain shape be interpreted as the realization of a certain basic type. And the good thing is: a) computer scientists have probably in general a much better theoretical grasping of such theoretical differenciations than art historians have (in tendency being rather averse to theorizing of method), and b) computer scientist have already worked for decades to emulate exactly the mental procedures in automated ways that are also being part of the Morellian method. In other words: the technological solutions, needed to implement Digital Lermolieff, at least in principle, do exist. And it is namely about two basic principles: the principle that automated signature verification systems are based on, and, more obviously, about face recognition systems that also are able to produce three-dimensional models from two-dimensional renderings of faces. And, heureka: also of ears.

FOUR) The Combination of Two Principles or: Digital Lermolieff

From what I do remember it happened only once to me that my bank did not accept my signature on a payment order, although I was entitled to give that order. My signature, obviously, as for that particular case, did not match whatever they did compare my signature to. I do not know exactly how these signature verification systems work, not to mention of their company secrets, but I do believe that these automated systems (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signature_recognition) do more or less work as follows:

By giving a sample signature I do give reference material to my bank: it can be scanned. My next signature will be automatically compared to the sample signature, and any further signature, given that it is accepted, will help the system to develop an abstracted type of my signature, taking into account also the parameters in which my signature develops or dynamically changes, and any new signature will be compared with that very type, based on the analysis of all accepted signatures. Which means that my next signature will not have to match precisely some scheme (a nightmare!), but has to match the type within some parameters that are to be defined by the system, i.e. by those who run the system. And it does happen, although as for the one mentioned case I do not know why, that a signature doesn’t match. And this is, more or less, how I do imagine that these systems work.

At any rate this is the one very principle inherent to the Morellian method. Style has been compared to an individual’s handwriting since the times of the Renaissance, and we have to keep in mind that we are speaking metaphorically. It is about a principle. And the principle says that it is not about a perfect matching of a scheme, nor an abstracted, idealized type that only does include characteristic features, but about the matching within certain limits that are being defined by those who run the system. Be it the one connoisseur, the one authority that is generally attributed authority to at the very moment, or the scientific community as a debating and, ideally, also self-correcting system that at any moment in time also makes it completely transparent as to what it actually does – for everyone interested to check.

The second principle inherent to the Morellian method is, of course, the very principle of facial recognition (see as an introduction: http://www.nzz.ch/aktuell/startseite/gesichter-treffsicher-erkennen-1.779271 and http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gesichtserkennung), whatever the database might be here (a 3D-scanning or the modelling of 3D-models, derived from 2D-images; and I might add: the latter is what the computer scientist, at Basel, are specialized in; the digitalized Mona Lisa, shown below as being part of a book cover, is developed by them).

If the two mentioned principles were now combined we might get at something that we would be entitled to call Digital Lermolieff: an application being able to develop ear (or hand, or whatever) types from given (already accepted) reference materials, and able to compare visual material in question with that type. Assuming that someone is able to teach a machine to do that, we still would need someone to interpret the outcome of such comparisons. In other words: we need someone to define what it does mean ›to match‹ and ›within certain limits‹, and to interpret this within the frame of what other attributional methods and also historical and material research have found.

Something more consistent than chance and more solid than fancy?

(picture: universal-prints.de)

And this is the point to say something in general as to the Morellian method, and as to what we are or were just doing here right now.

If this type of proceeding that we are virtually emulating here might appear fuzzy to someone, I would say: Yes, it reveals to be most fuzzy, but in my opinion a fuzziness that reveals itself is better than a fuzziness remaining hidden, being mystified and being covered up with a hard-science rhetoric of scientific objectivity (while the fuzziness is still lurking within, especially as to the many acts of interpretation involved in the applying of formal comparisons). In other words: it’s not the least to show how fuzzy, how burdened with all kinds of subjective interpretations the working with formal analogies (be it in 2D or in 3D) is and remains. And my personal opinion as to the Morellian method is that it has always looked good on a theoretical level (especially to philosophers), but as soon as one does enter the field of practice, one gets aware how numerous the various practical problems are. And the thinking through of the mental procedures comprised, for its own sake or to the benefit of actually realizing adequate technical applications, benefitting from one thing: the infinite storage capacity of today machines, storing also large visual databases, does only reveal these problems, this whole fuzziness gets revealed in blinding clarity. And it is not the least to this very end, he have tried to emulate Lermolieff in shape of a distant relative named Digital Lermolieff.

We think that the result is open to be discussed by everyone interested, but there are two things more to say: The one thing is that the fuzziness revealed here bears not only on the Morellian method in particular but on any connoisseurial practices that take into account formal analogies of whatever kind. Which means: the analogue practice of connoisseurs might not be less fuzzy – the fuzziness generally only remains better hidden, does usually not get revealed, even if connoisseurship, if stylistic criticism is meant to be one pillar that art history, as a science, does rest upon. And the second thing to say finally here is: Do keep in mind that it is one thing to isolate the practice of working with Morellian details, and another thing to first narrow the field with the applying of any other method, and finally to discuss if the working with c, to use the nomenclature introduced above in relation to ›style‹, does make a difference as to the attribution of a particular picture. What sceptical Giovanni Morelli practiced was definitely the latter, although to many it seemed to be the other way round.

PS 1: The Digital Lermolieff would also serve as a tool to observe the construction of visual types (as to human anatomy, landscape, architecture etc.), because one might also, while constructing types, based on numerous single examples, judge upon whether the construction of idealized types would make sense at all in a particular case, depending on the degree of regularity found in this particular case.

PS 2: As for Morelli the distinction between ›consciously‹ and ›unconsciously‹ produced regularities was of little importance here, because this distinction does bear on the theoretical explanation of why regularities that we subsume under the notion of style are found at all; however one may work with regularities found empirically, without knowing why such regularities do exist; nevertheless Morelli did differenciate, on a theoretical level, the formal regularities found due to the artist expressing his mind, and such that were merely mechanical habits of the hand (as the flourishes of a handwriting are).

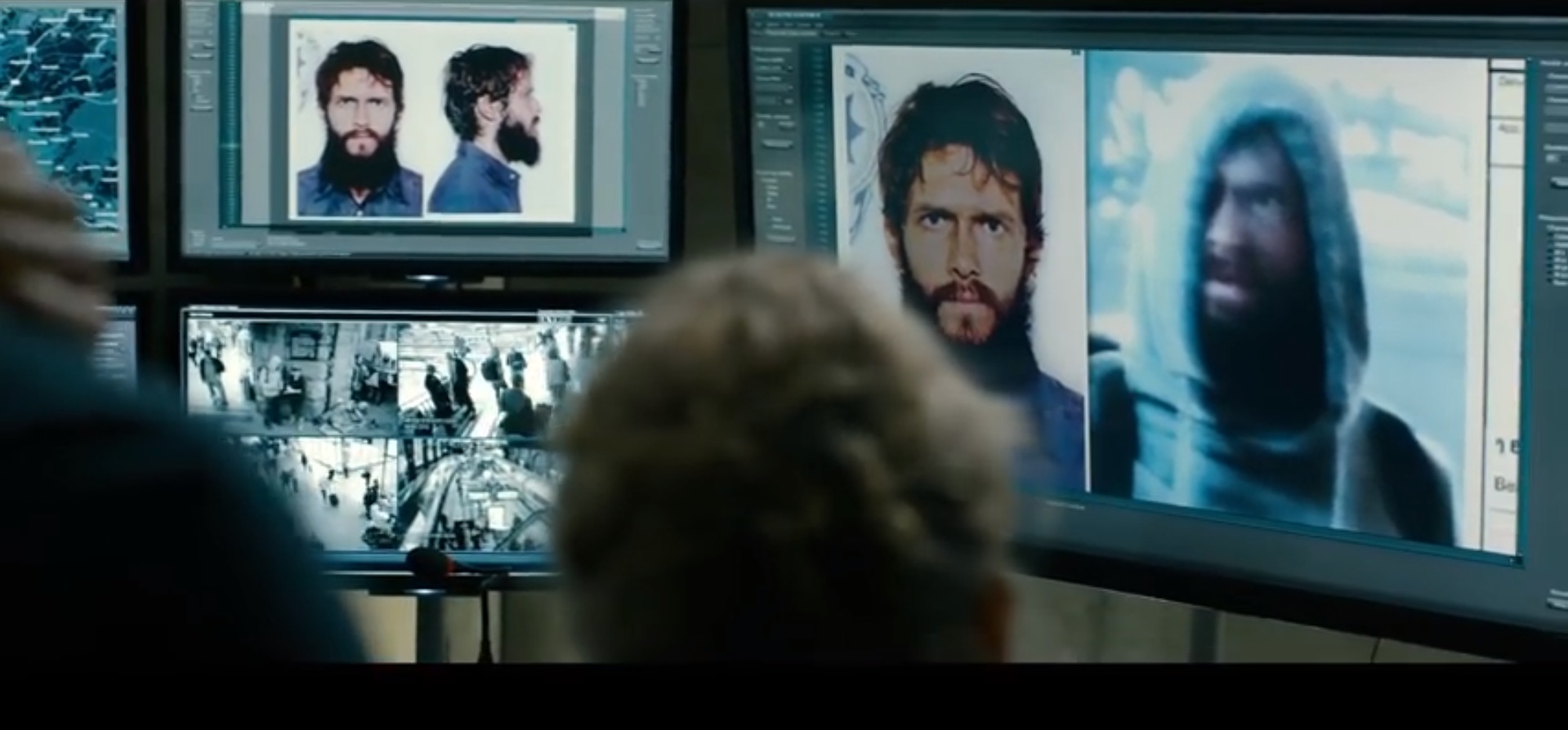

›The quality’s not great, but good enough to make a match‹ – still from A Most Wanted Man, 2014 movie by Anton Corbijn after the novel by John le Carré (picture: youtube.com/trailer)

FIVE) Some Notes as to the History of Digital Connoisseurship

C. 1964: early beginnings of automated face recognition systems [whose efficiency, up to the present date, might be called controversial]

1973: philosopher Richard Wollheim, more than 80 years after Morelli’s death, expresses his surprise that there has been so little empirical testing as to the Morellian method; he also muses about how the illustrations in Morelli’s book were to be taken, interpreted and to be applied at all (›as configurational or phenomenal models‹?)

1986: a computer lab is established at Gymnasium Oberwil [my comment: I am including this date to show that, at around this time, the learning of how to handle a computer was becoming something to be included in school curricula]

1987ff.: PC-supported signature verification systems are being developed due to demand of major financial institutions [I am relying here mainly on the notes as to the company history of Softpro (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Softpro) that Wikipedia, in 2015, after the company has been sold in 2014, still names as the world leader of this branch of technical solutions; signature verification systems have been developed as to the authenticating of signatures given on paper and, in the mean time also (but less relevant in our context) as to the authenticating of digital signatures]

1994: first automatic signature verification system goes into production

2003: Ivo Widjaja, Identifying Painters from Color Profiles of Skin Patches in Painting Images (University of Singapore, Department of Computer Science thesis: https://www.comp.nus.edu.sg/~leowwk/thesis/ivo.pdf)

2004: the computer is being named an ›art connoisseur‹ for the very first time (NZZ) which refers to technologies presented by three scientists of Dartmouth College applying wavelet analysis to analyze the brushwork of chosen painters (http://www.dartmouth.edu/~news/releases/2004/11/22.html); the MacPaint software is no longer being on the market

2011: the art historian and curator Anna Tummers does refer to the above mentioned technological developments in her The Eye of the Connoisseur [thus the new technologies, at least here, are in discussion also in the academical art historical field]

2012: according to a newsreport researchers at Lawrence Technological University of Michigan have taught a computer to compare paintings by 34 artists [from the one newsreport I got, it does not get quite clear what the machine was actually able to do and why; apparently the researchers were able to teach the machine to recognize similarities [which ones?] in works by Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst and Giorgio de Chirico; and the press interpreted this as the machine being able to ›recognize‹ that works by these artists show a ›comparable style‹ (to whatever similarities this might bear on); I am including this to show that also informations are given in circulation that I would describe as being rather ›suggestive‹ than really informative, and that probably were made known rather with the aim to entertain than really to reflect what’s happening on this front of technology and why]

2014: wavelet analysis being applied to paintings by Vincent van Gogh is also an issue at the ›Authentication in Art‹ conference held at The Hague (compare: http://ecee.colorado.edu/~smhughes/HendriksHughesVanGoghsBrushstrokesMarksofAuthenticity.pdf)

2015: The Digital Lermolieff

(Picture: presseportal.ch/Volker Blanz/Thomas Vetter)

(Picture: migros-kulturprozent.ch/Volker Blanz/Thomas Vetter)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS