M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

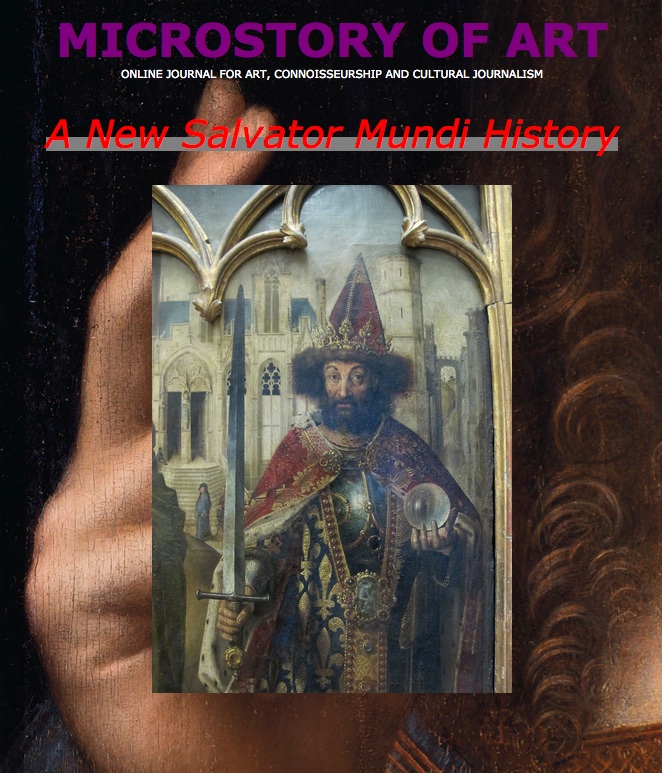

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Bettina von Arnim

Bettina von Arnim in 1838 (picture: Fembio.org)

Carl Friedrich von Rumohr as seen by Friedrich Nerly

When 22year old Giovanni Morelli came to Berlin in 1838 he knew that Bettina von Arnim (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bettina_von_Arnim) was, as it were, a point of interest. He waited rather long to pay her a visit (at least he said so in his letters to his friend Genelli), and this although probably Bettina’s brother Clemens Brentano (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clemens_Brentano), who lived in Munich, where Morelli had been studying, had provided him with an entrance.

But maybe it took him some time to prepare for this visit by reading the Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde that, among other things, had made Bettina famous. And maybe it was by reading this two volumes book that he made, like we do now, an acquaintance with Carl Friedrich von Rumohr (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Friedrich_von_Rumohr), as seen through Bettina von Arnim’s eyes.

We don’t know if this particular letter adressed to Goethe was a letter that Bettina actually had sent to the latter in 1809 (Bettina did not instruct her readers how to read her book).

And we don’t know if the description of a stroll with Rumohr actually is (or is based on) an accurate account (her biographers struggle with that question and they seem to know that in 1809 24year old Bettina and 24year old Rumohr indeed did meet, when Bettina lived in Munich to take singing lessons with Peter Winter (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Winter) and Rumohr studied painting at the Munich academy).

And we don’t know if Morelli did ask Bettina about it, when in the summer of 1838, he spent quite a lot of time in her company (which included that she read to him some, as Morelli says, »recently composed« letters to Goethe to be included in a new edition of her already famous book). Morelli found these letters read to him beautiful, but apparently liked the icecream even more that Bettina’s servants got from Café Kranzler (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Café_Kranzler).

At the very end of his 1838 visit to Berlin (a city that he rather was meant to dislike all his life) Morelli actually got to know Rumohr personally. And maybe the reading of Bettina had prepared Morelli also for this actual, if brief meeting of his precedent as a foundational figure of scientific connoisseurship.

*

What we do now, however, is a mere reading of the description of Rumohr by Bettina as a literary text. We don’t care here if this stroll with Rumohr actually did take place or if the description of Rumohr is accurate. We just take it, like Bettina probably would have wanted us to, as if it had been. Thus we consider the literary nature of her work as an invitation just to follow our streams of associations or in other words: as an invitation to join the game of relating to persons, places, pictures and ideas, only we don’t mask our »letter« by suggesting that what we do here is an actual letter to Goethe, sent from the future to the past.

No watchmen protect the apple orchards anymore, and princesses, unlike those from the fairytales, do not wait for knights to get them anymore, but await the knight to charm him behind hedges. Which is just another way of saying that times have turned completely upside down. And Bettina is feeling muddled, melancholy. It’s the spring of 1809 and the Tyrolean Rebellion (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyrolean_Rebellion) is what she’s so upset about (and she does wildly identify with the Tyroleans). And she is muddled because she does not know to whom to turn to for giving her advice. The crown prince of Bavaria seems to represent the ideal of man, the ideal of unspoiled youth. But times will spoil him, like politics has spoiled the king, who shows that cruelsome to the brave Tyroleans. And it’s virtue, one of these big words, that in these times spoils youth.

And from the distance one may hear the sounds of trumpets and of drums. To whom to turn to, if not writing one more letter? To Goethe (who may answer her or not)? Or pray to god? – It’s one hot afternoon in May. And there’s only Rumohr, but at least Rumohr there actually is. For a stroll of one and a half hour or so. Rumohr, who is not a king, but king, apparently, of his own fancies (and this is not least what’s muddling Bettina, because, obviously, she is not queen of hers).

But maybe she is. Much more that anyone would now expect. Because it is her fancy that stages all this. All that happens on this stroll with Rumohr. And what happens is that Rumohr simply falls asleep, or better simply takes a nap under a tree. Which may not exactly be appropriate but which is what gives Bettina now the chance to ask a few questions that are now on her mind after observing Rumohr for some time. A few questions she would rather not dare to ask (but why?) if Rumohr was awake.

In any case: we see now Rumohr taking a nap under a tree. He’s sleeping, resting, dreaming, while nature near the village of Harlaching is all around him. But questions of Bettina may nevertheless get through to him, according to Romantic theories of sleep and dream, just because he is not awake, but sleeping. Which is a state of mind of just higher receptiveness. Theories me may actually not need, because, indeed, we hear, we read the questions of Bettina. And here again we insert our link to the portrait of a resting, sleeping, dreaming connoisseur:

Rumohr does not speak to her, as far as we can say from her account. Rumohr is either being active without words or (for her standard: too) passive. And now he is seemingly passive but, if he does not speak, at least he got to listen. About being lazy (but it is Bettina who depicts him as lazy) and about being terribly sick of something that she despises: being terribly sick of neutrality. And here we would like to translate a bit of what Bettina says to sleeping Rumohr:

»How is it, that you have such compassion and that you are so friendly toward all animals, whereas you do not care about the mighty destiny of that people of the mountains? Few weeks ago, when the ice was breaking and the river rose over, you did risk everything to save a cat from the distress of water. The day before yesterday you did dig a grave with your own hand for a dog, beaten to death, that was lying near the way, and you did cover him with earth, although you were dressed in silk stockings and you did have a silk hat (Klaque) in your hand. This morning you did complain under tears that the neighbors would destroy a net of swallows despite your pleas and objections. Why does it not please you to sell your boredom, your melancholic fancy for a gun, you are so light and slim like a birch, you might jump over the abysses, from one rock to another, but lazy you are and terribly sick of neutrality.«

And instead of giving answer to Bettina who is standing on the very meadow where Rumohr does sleep under a tree, the connoisseur to be does »snor as for the flowers to tremble«.

While we are now looking at a sleeping hunter (as an alternative we point here to Nerly’s sleeping shepard at Kiel: http://www.museen-sh.de/Objekt/DE-MUS-076017/lido/555) we have to better understand of what Rumohr is being accused of. It is not lack of empathy, it is his selective empathy, his obviously not being drawn to people. And his being spoiled by something that others may refer to as a virtue: being neutral. And in sum what seems to puzzle her is that empathy and sensitivity can go along with not being committed to a political and military struggle (that she, however, is committed to). And if we follow that train of thought, it is not a lack of political conscience that Rumohr is being accused of, it seems to be more that he is drawing a line between areas Rumohr can feel and live empathy and areas that he has decided that he can not (or that it does make not sense). But here is exactly where the two, or the two voices within Bettina, differ. It’s about where exactly this line is to be drawn, and: if it is possible – a very comtemporary or even ageless question – not to look to the other side, where terrible struggles go on, while defining oneself as a man rather of contemplation than of action.

If we have understood what the scene of resting Rumohr is all about, we might become interested in where all this takes place. And the setting is not a mere Romantic or symbolical landscape, where just a tree would be of need, an apple orchard and a town or village close by. Not to mention a rushing river. This all, of course is needed as a setting, but it does make sense to situate the whole stroll rather precisely nearby Munich, because not only sounds of nature, but also sounds of musical instruments are needed, sounds of trumpets and drums, signaling movements of troops, coming back from fighting the rebellian (because this scene isn’t about the Romantic wanderer and about sounds of fontains, huntsmen’s horns or harps).

We show a historical picture of Harlaching below, which, today, is a part of Munich. And we show some pictures of the military affairs, that, if symbolically, are becoming present. The battle of Landshut took place in 1809 (and Bettina was to settle in Landshut even a little later in the very year). And the Tyrolian Rebellian became a subject for artists as well.

*

Resting Bettina, by the way, became a subject for a befriended draughtsman as well, and considering this we might as well consider the whole seen as a mere soliloquy of Bettina’s. But Rumohr has a second appearance, when he and Bettina cross an Isar bridge. This however shows a brave (and also wittily speaking) Rumohr, and a Bettina rather trembling on the rather rickety construction of a bridge.

She is still, or even more so puzzled, when returning home to Munich after one and a half hour or so stroll with Rumohr. At some occasion, maybe while returning home, Rumohr uses a stick to have a vast number of maybugs fly away. This seems not like Rumohr with his deep empathy for nature. But this again may seem a hidden motif of a military bearing, because maybugs, a swarm of maybugs, might as well remind of war because of the song Maikäfer flieg (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maikäfer_flieg) published in Des Knaben Wunderhorn (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Des_Knaben_Wunderhorn), just edited by Clemens Brentano, Bettina’s brother, and Achim von Arnim (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludwig_Achim_von_Arnim), whom she was to marry in 1811.

(Picture: Mein Bayern)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Carl Friedrich von Rumohr

(Picture: Zeno.org)

© DS