M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

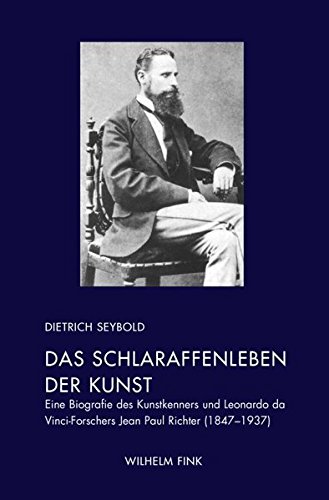

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

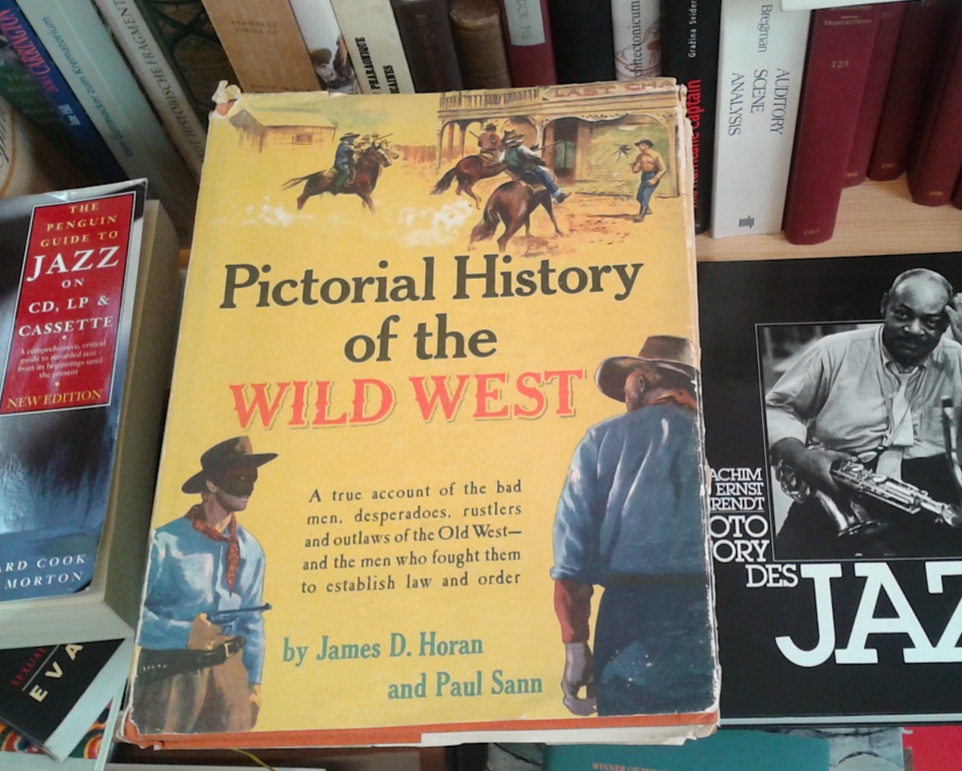

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

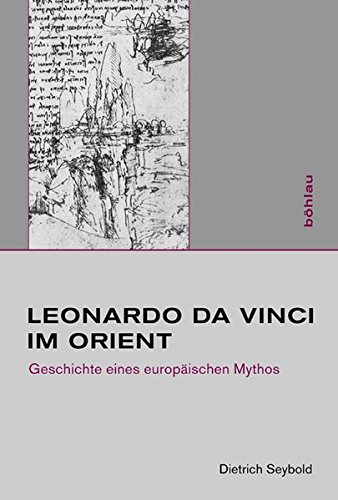

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

A 21st Century Renaissance of Connoisseurship

A 21st Century Renaissance of Connoisseurship

This is about the recent and international renewal of interest for connoisseurship (whatever may be understood by that term in and outside the academia). It is secondly about the question, if not the social type of connoisseur represents a needed social type between the social type of layman and the social type of expert, and in that does represents another relation to knowledge and to the cultivating of knowledge than these two other types. Thirdly it is about what cultures of connoisseurship actually do need to prosper within our contemporary cultures that are rather used to think of themselves as expert cultures.

One) A Recent Renewal

(Picture: nationalgallery.org.uk)

The internationally used term »connoisseurship« might have a slightly different fate than the German term »Kennerschaft«, but in about 2005 and the very years to follow »Kennerschaft« as well as »connoisseurship« were seen by some as being in a crisis. And here, for once, all seemed to refer to the same thing: a crisis as to how problems of attribution of artworks were being addressed and handled.

If in recent years a renewal of interest in connoisseurship may be diagnosed (while a certain uneasyness to use the very term, can also be observed), it might be partly because any crisis requires a rethinking of concepts and practices in itself. But on the other hand it seems that this renewal of interest is also due to a certain uneasyness with other concepts of art history. And it might be that many art historians around the world feel that in »connoisseurship«, although associated with many things disliked by many, and the very term sounding old-fashioned and even evoking snobbyness (the German term, on the other hand, at least in German ears, sounding rather neutral or even positive), it might be that in »connoisseurship« might also to be found something lacking in for example social history, poststructuralism and even the fashionable and again philosophically oriented »Bildwissenschaft« or »Bildkritik«. Let’s briefly review some dates:

In 2006 James Beck, in the subtitle of a book, spoke of »connoisseurship in crisis«; in 2009 Felix Thürlemann did see, referring also to earlier publications of his, »die Kennerschaft in Krise« (http://www.nzz.ch/nachrichten/kultur/literatur_und_kunst/die-kennerschaft-in-krise-1.1995824); but in 2010 the National Gallery of London, with their Fakes, Mistakes & Discoveries exhibition called Close Examination set another example: of a more relaxed dealing with – partly – the very gallery’s own mistakes and blunders, that where – surprisingly – exhibited to the world (like probably no other museum of that type had done before). And this exhibition responded to the popular fascination by problems that to solve demand a certain detective spirit (that, in comparism to connoisseurship, is generally seen as something very positive and less associated with snobbery and dubious art world practices). In brief: the figure of the art detective might be crucial to rethink and also to see connoisseurship in a positive new light. The art detective, horribile dictu, might even outshine the old-fashioned connoisseur. But these notions refer to types, and the reality, as always, is more complicated.

As usual, however, the academia responded much slower to crisis and renewal of interest, than the outside the mere academia art world sphere. But if art historians had traditionally rather drawn a line between practices of connoisseurship, that were to be situated in a somewhere inbetween the institutions of the museum, the university and the art market, it was, remarkably, in very recent years the academia that showed a new interest in connoisseurship. For example the 2012 CIHA congress with a section on »Art technology and Connoisseurship« (http://www.ciha2012.de/en/program/the-21-sections/section-8.html), the University of Zurich (in association with the Swiss institute for Kunstwissenschaft) with a 2013 symposion on the »expertise«, the German Kunsthistorikertag of 2013 with lectures dedicated to issues of connoisseurship, or the Kunsthistorisches Institut at Florence with a symposion on the German tradition of connoisseurship in the very same year.

(Picture: seonaidhceanneidigh.files.wordpress.com)

And two other factors might be named to explain the recent renewal of interest: the demand of progressing »Technical Art History« for cooperation with more traditionally working art history and also with specialists for the analysis of painting technique, found for example among restorers, a demand implicitly calling for a common platform where everybody might understand the other’s language at all. And the other factor being the various scandals and ongoing controversies within the art world (we name here, while we show a Goya print, only the Goya/Non-Goya-controversy of the »colossus« painting (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Colossus_%28painting%29).

For the probably very first time, it may be noticed here again, the various parties, including also lawyers, investors, collectors, sat together in a larger scale conference on authentication in art in the May of 2014 at the city of The Hague (http://www.authenticationinart.org).

It very much looks like that the appropriate answer to a crisis of or in connoisseurship, understood in the narrowest sense of the term, lies in a general search for smart cooperations, and not in a renewal of a connoisseurship that mystified the singular sensibilities of singular geniuses (that, by the way, were all male geniuses, without any exception, although many women were involved directly or indirectly in connoisseurship). And if this is true it has to be thought much more about the how of translating one language to speak and to think in to other languages and about standards and good practices, probably minimal standards, shared by all.

But the crisis and the recent renewal of interest for connoisseurship has a much more wider bearing, because it is not only about the problem of how to address and to handle problems of attribution. It is also about what culture of knowledge is desirable within the cultural sphere. And this is where, and this is where we want to open the perspective. In asking what the bearing of connoisseurship might be as to the relation to cultural objects and things, and as to the forms of knowledge that are specialized to deal with such objects. In sum: this is about how culture is dealt with, and about how cultures of connoisseurship deal with cultural objects, in comparism with, and even in opposition to, how scientific expert cultures deal with it.

...............................................................................................................................

Two) What Makes a Real Good Guide of Rome?

(Picture. colnect.net)

It is little known that one of the unfinished projects of German novelist Theodor Fontane (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodor_Fontane) was to write a biography of painter Carl Blechen (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Blechen). Fontane, who had an excellent sense for issues of connoisseurship, as we have already mentioned in another section, knew of the problems of such an undertaking. And one might add: he knew, as someone living on journalism, of the social classifications of his time, which also means: he knew of the demarcations between expert and layman, between expert and journalist and so on. But he obviously knew as well, despite his being very critical of phenomena associated with connoisseurship as for example pedantry (and German Gründlichkeit) that the phenomenon of connoisseurship itself was proper to undermine these demarcations. His attempt to put together an artist’s biography, though not being a scholar, might be seen as an attempt to show that a writer, journalist, though not being an expert and ›only‹ being a sometimes-art critic, could do justice to an artist nevertheless, and the attempt might have been motivated by Fontane’s views of connoisseurship, by his conscience that there was something other than scholar’s expertise and layman’s naive passion, and this is the point we would like to make here, because although never laid out as an elaborate theory, this conscience showns on many occasions in Fontane’s work.

In our section discussing the »Nightsides of Connoisseurship« we have mentioned the pedant husband of Effi Briest who is, as the old Briest has it, eager to re-catalogue every Italian gallery on his honeymoon trip.

In Fontane’s opus magnum Der Stechlin (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Der_Stechlin) we find as passage dealing with connoisseurship of architecture (and this is again about German Gründlichkeit):

Pince-nez, probably 19th century

(picture: etsy.com)

»Der Weg bis zur Kirche war ganz nah. Und nun standen sie dem Portal gegenüber.

Rex, zu dessen Ressort auch Kirchenbauliches gehörte, setzte sein Pincenez auf und musterte. ›Sehr interessant. Ich setze das Portal in die Zeit von Bischof Luger. Prämonstratenserbau. Wenn mich nicht alles täuscht, Anlehnung an die Brandenburger Krypte. Also sagen wir zwölfhundert. Wenn ich fragen darf, Herr von Stechlin, existieren Urkunden? Und war vielleicht Herr von Quast schon hier oder Geheimrat Adler, unser bester Kenner?‹

Dubslav geriet in eine kleine Verlegenheit, weil er sich einer solchen Gründlichkeit nicht gewärtigt hatte. […]« (p. 61 of a 1966 paperback edition)

Very significant in our context is the »kleine Verlegenheit«, the slight embarassment of Dubslav von Stechlin, because this is a clue how out of a sudden, if people gather in front of a church portal, it can be about levels of knowledge and potentially social differenciation. And Fontane, masterly, is not speaking about this, but showing this in his novel.

And it is not only his attempt to put together a biography of Carl Blechen, a project that, for whatever reasons, he did give up, that shows that Fontane felt not only as an observer of these matters of social differenciation by knowledge and by various types of knowledge. One marginal, seemingly innocent book review by Theodor Fontane lays out, if not a theory, at least the sketch of a theory of what real knowledge might mean – if it comes to cultural relations and things (and this is the area of knowledge that we are – exclusively – talking about here).

In 1865 Theodor Fontane had published a short review, entitled Nach Rom, that makes exactly one page (p. 552) in the volume Aufsätze zur bildenden Kunst (Erster Teil), published in 1970. It’s a review of a guide of Rome, of Rom und die Campagna by Theodor Fournier (second edition), to be precise. And Fontane found that this particular guide had united several qualities, that only »in the most rare cases« use to unite:

Don’t trust pictures – this room had to be rearranged for the taking of this photograph (picture: val-anhalt.de)

»Empiriker schreiben nach Augenschein ohne eigentliches Wissen; Männer der Wissenschaft aber andererseits schreiben aus toter Gelehrsamkeit heraus, ohne die lebendige Einwirkung des Gesehenhabens. Kommen aber ausnahmsweise Gelehrsamkeit und empirische Vertrautheit mit den Dingen zusammen, so pflegt dann wieder das feinere Verständnis zu fehlen, der angeborene Kunstsinn, ohne den sich freilich ein Durchschnittsbuch, eine Aufzählung des Sehenswerten, ausstaffiert mit historischen Notizen und vorgefundenen Urteilen, herstellen lässt, aber nicht ein Führer wie dieser, der, voller Sympathie mit den Dingen, die er beschreibt, nicht nur jegliche wünschenswerte Auskunft gibt, sondern anzuregen und zu unterhalten versteht. Herr Fournier hat eine Reihe von Jahren in Rom gelebt, und in die Kreise der römischen Gesellschaft eingeführt (das Buch ist der Gräfin Lovatelli gewidmet), sind ihm Dinge und in manchen Fällen auch wohl Aufschlüsse über die Dinge zugänglich geworden, die sich dem Auge Fremder zu entziehen pflegen.«

(to be continued)

...............................................................................................................................

Three) Connoisseurship and the Niche

(Picture: joycefoundation.ch)

In Winter of 1994/95, when being a student at Basel university, I attended a lecture series that I recall now and recognize as being one of the intellectual experiences that really had an impact on me. It was a lecture series called Epik der Welt, that had been organized by the Institute for Slavonic Studies (with Andreas Guski being responsible), and among the lecturers that spoke about the epic poetry of the world, there were capacities as for example Joachim Latacz (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joachim_Latacz), one of the leading capacities as to Homer, and there was Fritz Senn (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fritz_Senn), one of the leading capacities as to James Joyce. I have checked, if this event, or series of events, has left traces on the Internet, and I must say that sadly it has not. It is as if this event never had taken place, but it did (and since I had to check about the exact date, I had to dig down very deep into my archives). It did. And if history has not spoken about it, we have to change something about that here.

Because, as probably most people who have heard Joachim Latacz lecturing, I recall with what temperament he did introduce us to the Iliad in general, and to two types of Greek heroes, Achilles, the older, more archaic type, and to Odysseus, the younger, less archaic type, in particular.

But I have reason here to speak more about Fritz Senn, whom I recall as having been as equally inspiring in arousing enthusiasm for epic poetry, for literature in general, and at the time, I am coming to the point now, in winter of 1994/95, when attending this lecture series, I had no idea at all that – it has to be said – Senn had no actual academic degree at all.

Why does this matter? Is this to slight Senn, or to ignore his honorary academic degrees?

No, on the contrary. It is about showing that other intellectual – may I say? – careers (with a long ee) do exist, different from what within the academia is considered as being a career. As a career into working on or with literature, with passion, and with expertise. Within the academia it is probably not even generally known that such other spaces of knowledge and of passion, and of caring for literature do exist, might exist, and might have a right to exist, next to the academia.

Certainly, one does invite Fritz Senn to a lecture series, one does interview him, one does give him a prize. But no one ever explains to a young student, this is what you might do as well, and it may lead even to your coming back to the academic space, because after dire times, after difficult times, you may fight your way through whatever the circumstances are, and you may end up as, may one call it, a Kenner of James Joyce, i.e. as one of the leading authorities on Joyce, yet without any academic degree certifying your authority.

I am preferring the German term of Kenner here, because »connoisseur« has this ringing of snobbery. But how to become a Kenner of James Joyce?

Well, we won’t discuss the biography of Fritz Senn here in detail, but we have to mention that without a patron or a maecenas like Robert Holzach (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Holzach), who helped to make the Zurich Joyce Foundation possible (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zurich_James_Joyce_Foundation), this would probably not have been possible. And as we also imagine: without friendships, intellectual friendships, this would probably not have been possible either. But why not?

The Education of Achilles by James Barry

(Picture: storiadellarte.com)

Because within the academia there are certain other rules. By following your one main passion only, you might damage your career. By wanting to dedicate your life to the one passion, you are damaging your career. By not following the intellectual trends that everyone within your field thinks as being important, your will probably damage your career. Which is not to say at all that within the academia intellectual passion is absent. Not at all, and I have mentioned Joachim Latacz as someone inspiring a 23year old student here, not least to make a point that this is possible (you find, by the way, a portrait of Latacz here: http://www.judithrauch.de/Texte/latacz.html). But still there are other priorities, the seeking of a more of freedom, and there are other temperaments that do not fit in – in whatever an academic career is thought to be, by whom and on whatever authority this is defined.

Anyway, we come now to the cardinal question of where, if a future Kenner is meant to live, where does a Kenner live, how does a Kenner make his living, in sum: where does he or she find his or her niche (if not within the academia, but still with equal right)?

(to be continued)

The Departure of Ulysses from the Land of the Pheacians by Claude Lorrain

And check out Joachim Latacz being interviewed here, speaking about the beauty and intelligence of Helena: http://www.weltwoche.ch/ausgaben/2009-52/artikel-2009-52-seite-78.html.

(Source: funny-pictures.picphotos.net)

Back to the starting page of Dietrich Seybold’s homepage: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/HomePage

© DS